Reviewed by RICHARD & KAREN LA PORTE:

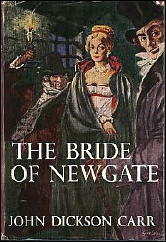

JOHN DICKSON CARR – The Bride of Newgate. Harper & Brothers, hardcover, 1950. Paperback reprints include: Avon 476, 1952; Avon T-391, 1960; Curtis, 1971; Carroll & Graf, 1986.

Dick Darwent is to be hanged in front of Newgate Prison at dawn tomorrow for a murder he did not commit. Caroline Ross must be married in order to collect a legacy, but she does not want a husband. An unholy alliance is made to make her an almost instant widow, and Reverend Horace Cotton, the Ordinary of Newgate, performs the ceremony in Darwent’s cell.

“The Bride of Newgate” returns to her friends and their pre-hanging party across the street from the gallows. But fate in the form of the Battle of Waterloo cuts down Dick’s uncle and two cousins in the prime of their lives and leaves Darwent the family title. Dick, now a Peer, can only be tried in the House of Lords, who forthwith pardon him.

The year is 1815. Now armed with a title, money and property, Darwent can track down the evil “Coachman” responsible for the murder that he was to be hanged for. Caroline, heiress and marchioness, falls one-sidedly in love with Dick. Married in name only, she aids and abets his search to unravel the twisted background of the crime.

Through a set of interlocking puzzles, Dick finds out that he was kidnapped and framed by mistake. With duels, a disappearing room, brawls and arson, the action is fast and violent. The London of 1815 is wrapped around the story until you can almost smell it.

Reverend Cotton is only one of a cast of colorful characters winging in and out of this spectacle. Scenes range from the House of Lords and the gaming clubs of Mayfair to the meanest gin shops in the East End.

Time has not tarnished this tale. John Dickson Carr was as noted for his historical fiction as he was for his locked room stories with Dr. Gideon Fell and Sir Henry Merrivale. This fresh reprint [from Carroll & Graf] makes another fascinating story available in a handsomely bound paperback.

— Reprinted from The Poisoned Pen, Vol. 7, No. 1, Fall-Winter 1987.

GOOD COP, BAD COP:

Inspector French & Inspector Rebus

by Curt J. Evans

In his Rough Guide to Crime Fiction (2007) [reviewed here ] Barry Forshaw has a chapter, “Cops,” with 31 novel entries. Merely two of the novels listed were published before the 1980s: Ed McBain’s The Empty Hours (1962) and Georges Simenon’s The Madman of Bergerac (1932).

Ian Rankin, creator of Inspector John Rebus and currently the most popular crime fiction author in Britain, gets one entry, for The Falls (2001), as well as a page devoted to his works in general. Freeman Wills Crofts, creator of Inspector French, the greatest police detective of the Golden Age of detective fiction (roughly 1920-1940), gets no mention in the “Cops” chapter, nor anywhere else in Forshaw’s Guide for that matter.

This omission is an injustice to Freeman Wills Crofts. No doubt this author is out of fashion these days, but in his own way he is as important to the history of the crime fiction genre as Ian Rankin is. To be sure, Ian Rankin, the leading figure in the so-called “Tartan Noir” movement, has been a powerful force in moving British detective fiction away from its cozy, genteel, village and country house gentry stereotype, but in his own day Crofts did much the same thing, albeit more gently.

While Crofts’ most famous creation, Inspector French, is a much more conventionally “nice” individual than Rankin’s John Rebus, Crofts’ tales of French’s criminal investigations give readers a different picture of the Golden Age British detective novel than that which has been derived from the better-known works of the British Crime Queens (Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, Margery Allingham and Ngaio Marsh).

By exploring Freeman Wills Crofts’ Mystery in the Channel (1931) and Ian Rankin’s Hide and Seek (1990), I want to highlight not only the differences between Crofts and Rankin and their fictional detectives, but — which may be surprising to many — the similarities.

Crofts created Inspector Joseph French as a series character (he appeared in a long series of novels published between 1924 and 1957, the year of Crofts’ death) in order to get away from the eccentric amateur detective figure so strongly associated with British mystery. French won immediate popularity around the globe, becoming one of the best-known fictional crime investigators of the British Golden Age.

A plain, no-nonsense, middle class cop, Inspector French stands in stark contrast with such glamorous aristocratic sleuths as Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey, Allingham’s Albert Campion and Marsh’s Roderick Alleyn (though Alleyn himself is a cop, he is rather a twee one), as well as Christie’s eccentric Belgian, Hercule Poirot, and her nosy village spinster, Miss Jane Marple.

In 1936, Crofts’ American publisher, Dodd, Mead, informed potential Crofts readers that the author had deliberately built up Inspector French “as a foil to the theatrical and eccentric fictional sleuth” and that the police detective therefore was “a model of thoroughness, persistence and hardwork” — an ideal embodiment of the bourgeois virtues.

Mystery in the Channel, the seventh Inspector French novel, shows both the detective and the author at the height of their powers, in a typical case involving not misdoings in a baronial mansion or a quaint Edwardian village, but modern corporate corruption and crime involving two countries.

In the effective opening of Mystery in the Channel, the corpses of two men are discovered on a yacht adrift in the English Channel. Both men were felled by gun shots. It is soon discovered that the slain pair were officers in Moxon’s General Securities. (“You’ve heard of it, of course; one of the biggest financial houses in the country.”)

Could these deaths be related to the rumors in the City that Moxon’s was headed for a complete crash? It certainly seems so, when it is discovered that a million and a half pounds has been looted from the firm’s coffers.

Scotland Yard’s investigation involves delving into matters both financial and logistical. What were the two murdered businessmen doing on the yacht and who could have gotten on the yacht to murder them? To some this may sound dry, but Crofts manages to keep the reader in doubt and suspense until a dramatic climax is reached, when the dauntless French nabs the guilty.

In Mystery in the Channel, Crofts, a retired railway engineer who, admittedly, knew more about trains than he did the workings of Scotland Yard, makes some effort to portray the Yard as the great investigative machine that it was. Besides French, other officials seen working on the Channel case are:

â— Sir Mortimer Ellison, Assistant Commissioner of Scotland Yard, French’s boss throughout the series.

â— Police Sergeant Carter, French’s chief underling throughout much of the series.

â— Inspectors Tanner and Willis. These men both featured in earlier, pre-French Crofts’ novels investigating cases of their own, Tanner in The Ponson Case (1921) and Willis in The Pit-Prop Syndicate (1922). Tanner, we learn, is Inspector French’s “greatest friend.”

â— Mr. Honeyford, “finance expert from the home office.”

â— Inspector Barnes, “the Yard’s nautical expert.”

French also has to deal with local law enforcement officials in both England and France.

Admittedly, Crofts’ treatment of the police often is naïve, but his books certainly mark a departure from the Golden Age stereotype of amateur detective and country houses/villages. How does Crofts compare with Rankin, a hugely popular author widely deemed the modern master of the British police procedural?

Hide and Seek, the second Ian Rankin novel about Inspector John Rebus, appeared in 1990. In this tale, Rebus investigates the death of a young male drug addict found expired, surrounded by Satanic symbols, in a squalid Edinburgh “squat” (abandoned building).

Everyone but Rebus writes the death off as an accidental overdose, but the tenacious and stubborn detective eventually discovers darker truths, namely that the young man was murdered and that a malign conspiracy involving very prominent people is afoot in Edinburgh.

On the surface Inspectors French and Rebus are very different sorts — one might call them British crime fiction’s good cop and bad cop. French has an ideally blissful marriage with his wife, Emily, or Em; and he has a daughter, Eliza. (To be sure, there is tragedy in French’s life in that his son was killed in the Great War, but Crofts later forgot that he had given Joseph and Emily children, so perhaps this loss does not matter so much.)

Although in a couple of Crofts’ novels Em has what she calls a “notion” and contributes an insight that helps French solve his case, essentially she is a firmly domesticated woman placidly devoted to her husband’s welfare and what the author terms her “mysterious household employments.”

Contrastingly, in Hide and Seek we learn that John Rebus’s wife has left him and his household behind, taking their daughter, Samantha (Sammy), with her. Rebus leads a much lonelier, angst-filled existence than French, and he has no one to tidily arrange his domestic life.

Instead, he goes through a series of girlfriends, drinks too much and smokes too much — all patterns of behavior alien to the the abstemious and upright Joseph French. (It is rather shocking when a frustrated French at one point in Mystery in the Channel declares, “Curse it…I could do with a bottle of beer.”) Like French, Rebus seems to have some religious inclinations, but, unlike French, Rebus is unable to sustain them.

Rebus also has pricklier relationships with his superiors than does French, although Rankin’s old-fashioned and courtly Detective Chief Superintendent Thomas “The Farmer” Watson bears considerable resemblance to Crofts’ Sir Mortimer Ellison. (Over the course of the Rebus novels things continue to change, however: Watson retires in 2001’s The Falls and is replaced by a woman — awkwardly for Rebus one of his former sexual partners.)

Nevertheless, French as well as Rebus sometimes bucks the system. In Hide and Seek, Rebus finally exposes the criminals by a not-by-the-book stratagem that is like something Bulldog Drummond and his jolly amateur crime fighting pals might have tried in an outrageous Sapper thriller from the 1920s.

For his part, French for the sake of expediency on occasion employs skeleton keys to conduct warrantless searches and sometimes “bluffs” recalcitrant witnesses (misleadingly threatens them with arrest) to get the information he wants.

Not surprisingly, given the tenor of modern times, Rebus’s cases tend to involve much racier subject matters — bad stuff — than those of Inspector French. In Hide and Seek, for example, Rebus confronts a case involving such unsettling matters as Satanism, drug abuse and (male) prostitution. Certainly no such things crop up in Crofts’ Mystery in the Channel!

Yet in a key respect the subject matters of the books are strikingly similar. In both Hide and Seek and Mystery in the Channel, the specter of business corruption and criminality looms large indeed. Both Rankin and Crofts take quite condemnatory views of the corporate world. Here is Sir Mortimer Ellison on the men of Moxon’s General Securities:

“[W]hen I think of all the innocent people who are going to suffer through these dirty scoundrels, I’d give a big part of my salary to know they were safe in Dartmoor….I tell you, French, it’ll not be the fault of this department if those fellows have any more happiness in this world.”

The author himself chimes in with a similar note, informing us of Sir Mortimer that “for the wealthy thief who stole by the manipulation of stocks and shares and other less creditable methods known to high finance, whether actually within or without the limits of the law, he had only the most profound enmity and contempt.”

In his influential survey of detective and crime fiction, Bloody Murder, Julian Symons declares that “Golden Age writers would not have held it against [E. C. Bentley’s Trent’s Last Case character Sigsbee] Manderson that he became rich by speculation.”

By making such an assertion, Symons reveals he did not sufficiently comprehend the work of Freeman Wills Crofts. When writing Mystery in the Channel Crofts clearly was influenced by the deplorable state of the world since 1929, after the Wall Street Crash and the onset of the Great Depression (events that also have resonance today).

In Hide and Seek Rankin makes his distaste with Big Business as manifest as Crofts had sixty years earlier. Mark the words Rankin puts into the mouth of one of his businessmen villains, who arrogantly attempts to bribe Rebus:

“There’s a lot of new money in Edinburgh, John. Money for all. Would you like money? Would you like a sharper edge to your life? Don’t tell me you’re happy in your little flat, with your music and your books and your bottles of wine.”

But John Rebus, like Joseph French, proves sterling and incorruptible. In the end, Rebus and French share this defining quality with each other and, indeed, with Wimsey, Campion, Alleyn, Poirot, Marple and the rest of the crime and mystery genre’s Great Detectives: a determination to find answers, to establish truth, to restore some semblance of order in a world of chaos and confusion.

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

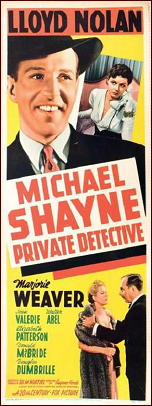

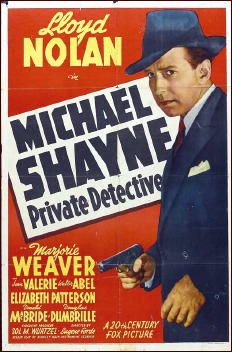

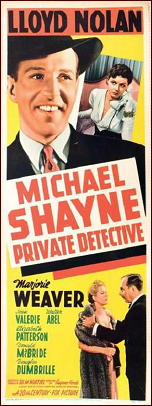

MICHAEL SHAYNE, PRIVATE DETECTIVE. 20th Century Fox, 1940. Screenplay by Stanley Rauh and Manning O’Conner based on the novel Dividend on Death by Brett Halliday. Director: Eugene Forde.

Lloyd Nolan plays Mike Shayne; Marjorie Weaver is the spirited female protagonist; Joan Valerie plays the femme fatale; Donald MacBride is the irascible, incompetent police chief (Peter Painter) with an even dumber but less irascible sidekick, Michael Morris; Walter Abel, Douglas Dumbrille, Clarence Kolb, and George Meeker impersonate a quartet of heavies and candidates for chief murder suspect.

Irving Bacon, who was regularly flattened by Arthur Lake as he tried to deliver the mail to the Bumstead residence in the popular Columbia series has a cameo as a fisherman neatly manipulated by Shayne into concealing testimony that would have implicated the latter in the murder.

This is a race-track, night-club mystery and is notable for two things:

Some really dumb situations for Shayne (his car stalls at the murder scene as the police are arriving; he throws what he believes to be the murder weapon — his own gun — into the bushes from which he handily retrieves it the next day after the police have presumably searched the area; he sticks his head into a dark room into which a man with a gun has just fled and is knocked out by the mug; and in the hoariest and most predictably resolved plot gimmick in the film, he stages a mock murder using ketchup as blood, and when he attempts to play out his mini-drama, discovers that the ketchup has been enriched with some very real blood, from a fatal bullet wound).

…And the introduction of a Little Old Lady detective (Elizabeth Patterson) whom he embraces at the end as his “partner” while he whispers to her, “And we’ll split the money.”

I have not seen one of these Lloyd Nolan Shayne films in forty years. I would hope the others in the series have aged better. Patterson is a graceful actress who makes the best of an awkward role. She has read all the Ellery Queen mysteries and the Baffle Book and she keeps wanting to share a particularly difficult “baffle” with Shayne.

Superior to The Gracie Allen Murder Case, to take an contemporaneous example, but you may not see that as a recommendation.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 8, No. 4, July-August 1986 (very slightly revised).