February 2012

Monthly Archive

Sun 12 Feb 2012

Posted by Steve under

General[7] Comments

Herewith some items of interest, I hope, from here and there on the World Wide Web:

â— Coachwhip Publications, a “micropublisher” new to me, has already made enough early detective fiction available to keep me reading (and broke) for some time to come. Included in their mystery offerings are: Futrelle’s The Thinking Machine | A. J. Raffles, Gentleman Thief | Hamilton Cleek | Old Man in the Corner | Uncle Abner Mysteries | Thornley Colton, Blind Detective | Max Carrados | Thorpe Hazell Mysteries | The Legal Exploits of Randolph Mason | Addison Kent Mysteries | Complete Adventures of Romney Pringle | Flaxman Low | Luther Trant, Psychological Detective | Average Jones | and many many more.

â— Bill Lengeman has added a monthly podcast to his Traditional Mysteries blog. The first one is a Round Table discussion between several bloggers taking on the subject:

“How Much Sherlock is Too Much?”

â— Curt Evans and Patrick Ohl are having a multi-part discussion on the latter’s blog in which they discuss in detail the various characters in And Then There Were None, one of Agatha Christie’s best known novels. The most recent of these posts covers General Macarthur. (When I say in detail, I mean it.)

â— As I’ve mentioned before, you can listen to every episode of the CBS Radio Mystery Theater online, a great way to spend part of your own evening, or any time of the day, for that matter. Even better, earlier this week Todd Mason provided links on his blog to a long list of other online archives of “Radio Drama from the 1960s to Now.” (Scroll down.) Some are familiar to me, others not.

Sun 12 Feb 2012

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

ROMAN McDOUGALD – Lady Without Mercy. Simon & Schuster/Inner Sanctum Mystery, hardcover, 1948. No paperback edition.

An obscure book by an obscure author. There are only five copies available on ABE, for example, but the most any one of them will set you back is $14, including postage, which means not only is the supply low, but so is the demand. Is it worth such a meager outlay? With some qualifications, I’d say yes.

But first, let’s talk about the author. There are six books listed to his credit in the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, all published between 1944 and 1950, with three of them having Philip Cabot as the leading character. I’ve not read any, but one source I found online called him a private detective, a fact that interests me, but it’s also one I can’t confirm.

As for Lady Without Mercy, in many regards, it reads like a gothic romance, much like those that were all the rage in paperback through the 1960s and 70s, and truthfully I was all but ready to give up on it very early on, not knowing where the story was going and not having much of a reason to care.

I didn’t make a special note of a particular passage to show you to demonstrate this, so here’s one I’ve just now chosen at random. The story is told largely from Linda Travers’ perspective, and she’s only just arrived at the home of Kirk Ormond, the man she loves. Unfortunately he’s married, to a woman whose long expected death from leukemia has not occurred in three years since it was diagnosed. From page 11:

As Linda went upstairs with Mrs. Seitz [the housekeeper], she reflected that Alan’s words had been like the last, deliberate move in a subtle game whose implications had already become to frighten her. But then, she told herself, she might easily be imagining all this. She must not let a mere intuition run away with her. She would have to be quite rational about it, accepting the fact itself without any reservation of dread. Nobody would try to get in…

She is being taken up to a room which Rita, the ill woman, had chosen for her at the last minute. Alan is Dr. Wall, the husband of her half-sister, Isabel. Also in the house are Alan and Isabel’s 16-year-old twin daughters; Kirk’s sister; the housekeeper; and Alice Coulter, sort of a companion to Rita, and who has been encouraging her in an obsessive interest in the occult.

Adding to the extremely atmospheric nature of the tale are some very strange facts. No one knows how Rita has managed to postpone death so long, and in so doing, has managed to keep Linda and Kirk apart. What’s more — and here’s where things begin to get interesting — after a recent attack of her illness that Alan did not believe Rita would survive, she managed to pull through, and at the exact moment when she began to recover, her favorite pet dog died.

When Linda finds a bottle of poison in her room, after being wakened by an intruder during the night, she finds the idea of using it to rid herself of her rival irresistible. Each time she makes the attempt, however, Rita mysteriously survives, and even more ominously, another member of this extended household dies instead. Kirk, Linda’s lover, is of no help. He’s a mess, through and through, an utter weakling. What Linda sees in him, one can only wonder.

As for Miss Coulter … well, perhaps I’ve said enough. You’ll have to read the book for yourself to learn more, and if you’re a fan of hard-boiled fiction, you probably quit reading this review long ago. Suffice it to say, though, this is one the more unique murder mysteries I’ve ever had the fortuitous opportunity to read, and I’m glad I did.

Fri 10 Feb 2012

AN OLD-TIME RADIO REVIEW BY MICHAEL SHONK:

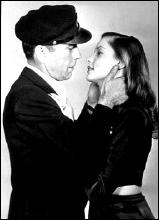

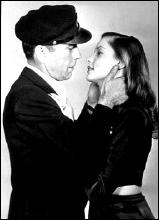

BOLD VENTURE. Syndicated; premiered March 26, 1951. Frederic W. Ziv Radio Production. Cast: Humphrey Bogart as Slate Shannon, Lauren Bacall as Sailor Duval, Jester Hairston as King Moses. Music: David Rose and his orchestra. Other credits (not given on air): Written by David Friedkin and Mort Fine. Directed by Henry Hayward.

Some interesting production information about the series:

The transcribed half-hour weekly was on over 400 stations by April 1951. It was first sold to local stations as a 52 weekly episodes package for $13 to $750 a week (depending on station size).

Bogart and Bacall signed a five-year contract for the show, got royalties earning them $5000 a week in the first year. Writers Fine and Friedkin got $1000 per episode in first year.

The first thirty-six episodes were done at once in early 1951 then Bogart and Bacall left on a European vacation. By the time the episodes aired Bogart was filming The African Queen. Reportedly there were 78 episodes done, but the number remains debated since most episodes had more than one title leading to some episodes getting counted twice. Today over fifty episodes survive. You can listen to many at Internet Archive here.

Bold Venture was a mix of the relationship between Bogart’s Harry to Bacall’s Slim in To Have and Have Not, toss in Sam from Casablanca and add “adventure, mystery and intrigue†in the “mysterious†Caribbean islands.

Slate Shannon was a former adventurer who had decided to settle in Havana Cuba and run a hotel called “Shannon’s Place.†He also rented out his services as Captain of his boat “The Bold Venture.â€

Sailor Duval was a young girl with a wild troubled past. When her father, an old friend of Slate, died he “willed†her to Slate to make sure she stayed safe.

Shannon was helped at the hotel by long time friend King Moses, who, when the story needed it, would sing a calypso song (by David Rose) recapping the episode’s story.

A popular source of stories was Slate’s “hobby†(as Sailor called it) of helping people, be it a neighbor who needed Slate to get his daughter away from a gangster or helping an old girlfriend who claimed she was going to be murdered by her stepmother.

“Shannon’s Place,†Slate’s hotel was a repeated cause to get Slate involved. Slate took it personally if anything happened at the hotel or to a guest, as when a beautiful female guest has her face ripped to shreds by killer gamecocks. In another episode Slate becomes a suspect when one of the hotel performers is killed. The script is available to read online here.

The final cause to get Slate involved was his boat “Bold Venture.†Slate and his boat would often be hired by clients who would lie about the real purpose of his trip such as gun running revolutionaries or a college educated treasure hunter turn killer out to retrieve stolen gold.

The stories were full of touches of crime fiction bordering on noir. Gunfire, fists, knifes, Slate getting beat up, Sailor in danger and countless dead bodies spiced up each week’s tale as our two heroes wisecracked and romanced through it all.

Strange characters were common, such as two schoolteachers out for excitement and adventure and willing to kill for it.

And what would this type of adventure mystery be without great dialog such as when Slate asks a man a question and the man replies toughly who’s asking, Sailor says “Him. I talk like this.â€

Then there was the final short scene (often called a “tag†or “epilogâ€) featuring Slate and Sailor and their relationship, usually ending with romance.

While the writing and music were enough to make Bold Venture a radio show worth listening to, it was Bogart and Bacall that made Bold Venture special. Their chemistry together translated to radio as well as film and real life. Plus, Bogart and Bacall could do something not many movie stars could, they could act with just their voice.

It would be the absence of Bogart and Bacall and that chemistry that would doom the Bold Venture TV series, but more about that next time.

ADDITIONAL SOURCES:

Billboard magazine, 1/31/51

Broadcasting, 4/16/51

OTRR Wiki page. (L. A. Times article by Walter Ames)

Fri 10 Feb 2012

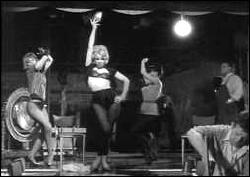

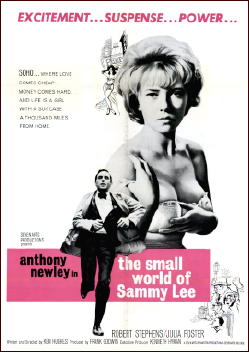

THE SMALL WORLD OF SAMMY LEE. British Lion Films, 1963. Anthony Newley, Julia Foster, Robert Stephens, Wilfrid Brambell, Warren Mitchell, Miriam Karlin, Kenneth J. Warren, Clive Colin Bowler, Toni Palmer, Harry Locke. Screenwriter: Ken Hughes, based on his BBC-TV play “Sammy.†Director: Ken Hughes.

One of Anthony Newley’s first dramatic roles, and it’s a good one, at least if you were to ask me. Bosley Crowther of the New York Times thought it was a bore, and a reviewer for the Village Voice thought the tawdry portrayal of the Soho strip tease club where Sammy Lee works as the emcee between acts (or compère, to use the big word I just learned) was hypocritical and just plain wrong-headed. “…some of our most distinguished citizens have been devotees of this art form.â€

Without going into the merits of stripping as a fine art as it occurs on some stages, on others tawdry, crude and sleazy are the only words that apply. Not that we see any real nudity in Sammy’s place of employment, but just hanging around backstage through the unblinking eye of the camera is a real, well, eyeful.

What makes Sammy run, though – this Sammy Lee, not the other one – is that he’s up to his neck in debt to a bookie who’s as tough as they come, and so are the hoodlums who work for him. If he can’t come up with £300 in five hours, his goose will be cooked, figuratively if not literally. To raise the money, he frantically scours his little black book in search of any kind of deal he can come up with: whiskey, bar glasses, watches, you name it.

Dashing here and there between shows with a breathless kind of nervous energy that will either annoy you immensely (see above) or keep you watching with a kind of fascination not at all unlike watching a train wreck about to happen. Beautifully filmed on location in black and white to a jazzy background beat, with a bit of romance on the side (with Julia Foster as Patsy, a fresh young innocent from the north country), if only he could slow down long enough to know what he has, if only.

You’ll have to watch for yourself to learn whether he comes up with the money or not. I might warn you that this a noir film from beginning to end, but sometimes reviewers do not tell you the entire truth, lest they give away too much, and this may be one of those times.

To return to my first paragraph, I don’t know what it means if I were to point out that both reviewers I mentioned were from the US, and a few years back The Small World of Sammy Lee was one of the movies on The Guardian’s list of 1000 films to see before you die. It must mean something, though.

[UPDATE.] It is now several days after I wrote the first draft of this review. In the version above, I gently chided the reviewer from the Village Voice about his opinion of this film, but he did point out several flaws, as he saw them, in the plot itself.

I saw them, too, but I’ve been thinking them over, and at the moment I don’t see them as flaws. Sammy Lee may have been a two-bit hustler, if not an out-and-out grifter, but I think he had moral standards. They may not have been your moral standards, nor mine, but he lived his life by them, and I can’t see any reason why I should fault him for that.

Fri 10 Feb 2012

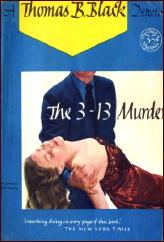

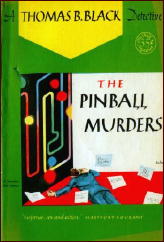

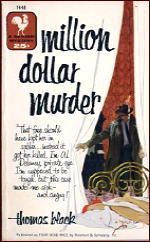

THOMAS BLACK – Four Dead Mice. Rinehart & Company, hardcover, 1954. Bantam #1448, paperback, 1956, as Million Dollar Murder.

I’m going to change things around from the way they usually occur here, not just a little, but from top to bottom. Instead of a complete list of Thomas [B.] Black’s private eye Al Delany character at the end of this review, here they are at the beginning:

The 3-13 Murders. Reynal & Hitchcock, 1946.

The Whitebird Murders. Reynal & Hitchcock, 1946.

The Pinball Murders. Reynal & Hitchcock, 1947.

Four Dead Mice. Rinehart & Co., 1954.

There are are only the four of them, and why the gap, and why the abrupt end to the series, I do not know. I’d welcome any information that you might have. According to Al Hubin, Thomas Black was born in Kansas in 1910, with a possible death date of 1993, not confirmed. (Information on hand as of the current Revised Crime Fiction IV.)

I’m sure I’ve read at least one of the first three, but it was so long ago, I’ll not rely on memory, and I’ll report on only this one. It takes place in Chancellor City, an small metropolis with more than its share of alleys, back streets, rundown housing and a wide-open red light district. I had the feeling that it might be St. Louis, in disguise, or Kansas City, perhaps, but that’s only a guess, and it’s probably not relevant anyway.

Delany is asked by a bakery to find out who might have dropped some dead mice into a vat of bread dough, and the case escalates from there to include the death of a job applicant who flunked an employment check, and more.

The dialogue is bright and chipper and slangy, and maybe some of the slang makes the book unreprintable today. For example, S.Q.Q. stands for? San Quentin Quail, if that helps any, and that’s what Delaney knows what Honey Ward is, a precocious young girl (in ways also probably unreprintable today) who grabs his attention early on and doesn’t let go.

Here’s an early scene that doesn’t have anything to do with the plot, and Cora Collins doesn’t appear again, but I liked the flavor it provided:

The bus had “East Side” on its green destination blind, and standing room only, and I swayed to a handstrap between two oblivious middle-aged vivisectionists who had a job to do and didn’t care who knew it. They were dismembering one Cora Collins, absent, and though Cora was pretty sad generally, her basic errors were three: she had fluffy blonde hair, owned a pseudo mink coat, and her best physical features could be purchased at any drug counter. As the two ladies carved and cut, the bus belly-crawled across C.C.’s graying traffic-congested streets, when I got down on the east bank of the ice-bleak Charles River, I had all the dope on Cora I needed; everything, that is, except her address.

From a little later on, from page 37, this excerpt is getting closer to the plot:

…Though I would have liked to have carried the thing further, I didn’t. J. Albert [Benson] was a client and a good one. I told him bowing-out time had come, and after we’d said the conventional things I headed back downtown via Adair Avenue, and on the way in I did a little mental work, finding it nothing but frustrating. It was a small world for sure. Honey had led me to Jack Doyle on the Grand Bridge, he had taken me to Margaret Benson in her Packard, and happenstance had guided me to the Benson place to be on hand when she arrived home. From playing bridge? I didn’t know, but it was a fine night for liars. Honey had lied to me about knowing Reymon, Mrs. B seemed to be lying about here whereabouts of the evening, and it was altogether possible that J. Albert’s secretary, icy Miss Hassett, was living a lie herself, covering an affair for her employer’s wife.

With other characters involved named Delight (a big nut-brown colored hairpin, handsome as sin and better proportioned), “Baggy Pants” Vance, Bam Carson, George Washington Hite, Little Phil Murio, and a hophead named Sleepy-Sleep, this reads like a cross between Damon Runyon and Harry Stephen Keeler, with triple the coherency of the latter, thanks to numerous recaps and timetables and lists of questions that haven’t have been answered yet.

I’m not so sure about the ending. I wish Black had pumped up the descriptions of some of the characters earlier on, to give them the presence they needed to fit the roles they were designed to play — and I’m not (necessarily) referring to the killer(s). As it is, it’s solid detection on the run, winging it as it goes, and cramming it all in to fit (for the most part) until the number of pages runs out.

–September 2003

[UPDATE] 02-10-12. I’m sorry to say that this is all I remember of this book. If I hadn’t written the review, I wouldn’t even be able to tell you where the four dead mice came in. I think this is a positive review, however. I’ve convinced myself I ought to read the book again, next time I get the chance.

Wed 8 Feb 2012

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[10] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

RUSSELL THORNDIKE – The Slype. Dial Press, hardcover, 1928. First published in the UK: Holden, hardcover, 1927. Also: Jonathan Cape, UK, 1933.

Forget about the plot in this thriller, which must have creaked even in the ’20s and which Thorndike does not energize or even, I must confide, make much sense of at the end.

It has to do with a treasure hunt by a flagitious doctor of medicine who is featureless and a Chinese villain who in his brief appearance manifests great charm despite his lust for the heroine and despite his vile antecedents and even viler predilections.

Most of the events take place in the fascinating Dullchester Cathedral. In the Precincts strange disappearances are occurring. A Minor Canon vanishes, followed shortly by a second Minor Canon. Then the spinster bee lady, complete with veil, is found missing, if that makes any sense. Soon the Dean, a speckled pig — the rest of the sty goes later — and a wind-up toy cannot be located.

As I said, the plot is not the reason to read this novel; it should be read for Thorndike’s descriptive ability and his characters. Foremost among them are Sergeant Wurren of the Dullchester Constabulary as he goes about his bumbling investigations and ludicrous questioning, and Wurren’s nemesis, Boyce’s Boy — you know, the lad who delivers for the greengrocer — a most extraordinarily intelligent and amusing imp. These two, and some minor characters, are worthy of being compared to Dickens’s creations.

First-class entertainment if you aren’t a plot person.

By the way, a slype is a covered passage, especially one from the transept of a cathedral to the chapter house.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 12, No. 4, Fall 1990.

Editorial Comments: Thank goodness, I thought when I read it, Bill added that last parenthetical paragraph. I had no idea what a “slype” was, and I still wonder what it has to do with the story. I will have to read the book. It sounds terrific.

Bill also used the word “flagitious” in his review. Neither my spellchecker nor I remembered ever having seen the word before, so I had to look it up. It means “criminal” or “villainous.” I love learning new words, especially those I can now use in my own reviews.

Of the author of this book, Russell Thorndike, I know nothing, except that he also wrote seven books of the adventures of smuggler-hero Dr. Syn, none of which I’ve read, nor I have I seen the Disney TV miniseries The Scarecrow of Romney Marsh, based on the first of them.

Tue 7 Feb 2012

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

NINE GIRLS. Columbia, 1944. Ann Harding, Evelyn Keyes, Jinx Falkenburg, Anita Louise, Leslie Brooks, Jeff Donnell, Nina Foch, Lynn Merrick, Shirley Mills, Marcia Mae Jones, Williard Robertston, William Demarest, Lester Matthews, Grady Sutton. Director: Leigh Jason. Shown at Cinecon 39, Hollywood CA, Aug-Sept 2003.

This was the third of the Leigh Jason films that have become an eagerly awaited event at Cinecon. (The earlier films were Dangerous Blondes and Three Girls About Town.)

A bevy of sorority sisters, chaperoned by Ann Harding (recovered from her tragic demise in East Lynne), drives to a mountain lodge where almost immediately Anita Louise, the most unpleasant member of the group, is murdered. Nina Foch and Evelyn Keyes are the prime suspects as the cops arrive and the entire crew is prevented from leaving by a convenient storm.

The humor is somewhat broader (and less effective) than in the other two films, but this was still a delightful film. The screenwriters (Karen DeWolf and Connie Lee) also wrote for the Blondie series, one of my early affections (or rather, Penny Singleton was the affection).

Editorial Comments: My own review of this film appeared earlier on this blog. Check it out here. Of the three lobby cards shown below, only the first two are (as I recall) from the movie itself. I have a feeling that the one at the bottom (with the girls in bathing suits) is only a promotional pose.

Tue 7 Feb 2012

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[14] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

W. R. BURNETT – Underdog. Knopf, hardcover, 1957. Bantam A1819, paperback, 1958.

Underdog finds W.R. Burnett at the top of his form, which is about the best there is. Clinch, the aptly-named, emotionally-constipated anti-hero of the piece, is an ex-con working as a chauffeur to a powerful political boss who befriended him in prison.

He isn’t long on the job, though, when he discovers (a) that his boss has a lovely and restless wife, and (b) the up-and-coming powers-that-will-be want to put said boss out to pasture — and whether he’s eased out or carried out depends on how much trouble he gives them.

Naturally, for this sort of thing, the Boss makes trouble for the new guys, and Clinch finds himself framed for murder, whereupon Burnett puts his own special slant on the old same song: Clinch doesn’t try to clear himself or catch the real killers; he just goes out to get back at the mugs what done him dirty. And what he does and how he does it makes for some of the most taut and violent reading to come my way lately.

Burnett was one of the few writers who could carry off this sort of thing perfectly. He evokes Clinch as a memorably ordinary guy, out for himself but loyal to his friends and nagged by his relationship with an underage hooker who wants to be a wife to him.

Additionally, the Boss, his wife and their “associates” come off the page in neat cameos that linger in the mind. As for the action scenes, well they’re the kind of writing that put hard-boiled literature on the map, and I can recommend this highly to lovers of the stuff.

Mon 6 Feb 2012

A TV Movie Review by Michael Shonk

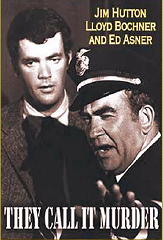

THEY CALL IT MURDER. TV movie, 17 Dec 1971. NBC / 20th Century Fox TV /Paisano Production. Based loosely on the book The D. A. Draws a Circle and characters created by Erle Stanley Gardner. Cast: Jim Hutton as D.A. Doug Selby, Lloyd Bochner as A.B. Carr, Jessica Walter as Jane, Leslie Nielsen as Frank, Jo Ann Pflug as Sylvia, Robert J. Wilke as Sheriff Rex Brandon, Edward Asner as Chief Otto Larkin. Written and developed by Sam Rolfe. Directed by Walter Grauman. Executive Producer: Cornwell Jackson. Associate Producer: William Kayden. Executive Story Consultant: Erle Stanley Gardner. Available on DVD and for downloading (Amazon).

This TV Movie pilot for NBC is the only time the Selby character has been adapted for TV or film. Doug Selby first appeared in Country Gentleman magazine in 1936. The first of a series of nine books, The D. A. Calls It Murder was published in 1937. This story was loosely based on the third book The D.A. Draws a Circle (1939).

There is evidence the TV movie was filmed in 1969 but did not air until December 17, 1971, and that Erle Stanley Gardner (Perry Mason) was involved. Garner died February 11, 1970, yet is credited as executive story consultant. Executive producer Cornwell Jackson was Gardner’s literary agent.

More than one reference book gives 1969 as the date made. In an article about Ed Asner (New York, March 15, 1982), Pete Hamill wrote than when Grant Tinker was casting Mary Tyler Moore in 1970 he remembered this pilot from his NBC executive days and asked Asner to read for the part of Lou Grant.

They Call It Murder was a better than average TV whodunit. Set in a small town called Madison City, Doug Shelby and Sheriff Brandon had recently won election pledging to keep the evil big city Los Angeles from taking over the town. The local Police Chief, Otto Larkin was on the other political side and supplies comedic relief. (He has his police car stolen while he is in it.)

A dead body is found in the swimming pool of Jane Antrim’s home. She shares her home with her disabled father-in-law Frank Antrim. Frank lost the use of his legs in a car accident that killed his son and Jane’s husband Brian. They are waiting for the insurance company to pay their $500,000 policy, but an insurance investigator refuses to approve the payout.

The victim did not die in the pool, but was shot elsewhere, twice, with two different guns using the same entrance hole. The first bullet killed him, but which gun fired the first bullet?

Selby spends his time interviewing suspects and potential witnesses, despite having his own “Paul Drake†aka Sheriff Brandon. The defense attorney’s “Hamilton Burger,†A.B. Carr arrives and actually beats Selby in the single very brief courtroom scene as Selby loses his fight to keep his murder suspect in Madison City jail. Instead the suspect is transferred to big city Los Angeles.

Selby realizes it all ties into the accident involving Frank and Brian a year ago. He asks his questions, nearly gets run off a mountain road by a bad guy, finds the clues and reveals all in the end.

Even Sam Rolfe (Man from U.NC.L.E., Delphi Bureau) was unable to install a personality into Hutton’s Selby. The script relied too much on the stiff boring Hutton and the equally boring Selby.

The supporting cast from the books was underused and their relationship to each other implied rather than explained. It was the relationship between Mason, Drake, Della, and Burger that made Perry Mason so much fun to watch. That was sacrificed here to focus on Selby.

I am not a fan of the puzzle mystery. I am a fan of Perry Mason but ignore the story until Mason gets involved. I rarely care who the murderer is. But this proved to be an interesting puzzle with who did it not as surprising as the twists in who did it.

There was little visually interesting about They Call It Murder, a whodunit more interested in clues than action. However the filming of the denouncement scene by director Walter Grauman was creative. As Selby explains, in voice over, what happened and who did what, the picture broke up into picture within a picture (slightly similar to the Mannix opening theme).

Fans of TV whodunits might enjoy They Call It Murder and wish it had been made a series. But the D.A. as the hero cop working for the establishment (compared to Perry Mason doing the opposite) did not have much appeal at that time. Plus, Hutton’s Selby had virtually no appeal as someone you would want to watch every week. They Call It Murder may have had a good whodunit, but it was no Perry Mason.

ADDITIONAL SOURCES:

Justice Denoted, by Terry White (Greenwood, 2003)

IMDB.com

Mon 6 Feb 2012

A TV Review by Mike Tooney

“Murder by Proxy.” An episode of Cannon (1971-76). Season 3, Episode 5. First broadcast: October 10, 1973. William Conrad (Frank Cannon), Anne Francis (Peggy Angel), Linden Chiles (Ray Younger), Marj Dusay (Mrs. Farrell), Charles Bateman (Lt. Paul Tarcher), Ross Hagen (Wendell Davis), Charles Seel (apartment house manager), James Nolan (Sparks Foster), Jack Gaynor (man). Writer: Robert W. Lenski. Director: Robert Douglas.

“Some years ago I devised, as an experiment, an inverted detective story in two parts. The first part was a minute and detailed description of a crime, setting forth the antecedents, motives, and all attendant circumstances. The reader had seen the crime committed, knew all about the criminal, and was in possession of all the facts. It would have seemed that there was nothing left to tell. But I calculated that the reader would be so occupied with the crime that he would overlook the evidence. And so it turned out. The second part, which described the investigation of the crime, had to most readers the effect of new matter. All the facts were known; but their evidential quality had not been recognized.” —

R. Austin Freeman, “The Art of the Detective Story” (1924)

There was a time when many, perhaps most, detective stories were whodunnits — the identity of the malefactor(s) would be withheld until the final “reveal” at the finale. (Personally, I prefer them.)

But there is another type of crime fiction called the “inverted detective story,” a kind pioneered by Freeman circa 1912, and which is so ably described by its inventor just above.

In the inverted, the reader/viewer knows more than the detective; and if done well, it can be just as entertaining as a whodunnit.

In the wake of the phenomenal success of the Columbo TV series, which with only one exception were all inverteds, other television shows tried their hand at it — bringing us to “Murder by Proxy.”

This particular Cannon episode could be regarded as a model of the form.

Peggy Angel (Francis) is a business woman who often frequents a certain bar after hours to unwind. She has no idea that she’s being set up to be framed for the murder of someone she doesn’t even know, by people she’s never even met.

The bartender slips her a mickey, and after a few minutes the world is just a blur to Peggy. The man with a mustache at the end of the bar offers to help her to her car– but when she comes to in an unfamiliar apartment with the murder weapon in her hand and a dead man on the floor, she understandably loses it.

As it turns out, the helpful man with the mustache (Chiles) is the murderer. He’s working on behalf of one of his clients (Dusay), for whom he has more than just professional feelings. (No, I’m not revealing too much — remember, the emphasis is not on whodunnit but “whydidtheydothat” and “howdowecatch’em.”)

With Peggy passed out on a couch, Younger (Chiles) goes about methodically executing his plan. The victim has been lured to the same apartment on some pretext, and Younger guns him down without compunction. He then moves a floor lamp from near the sliding doors to the other side of the room, gathers up some extension cords, stands on a chair to fetch something attached to a suction cup inside the skylight in the foyer, removes a tape from the cassette player, puts the gun in Peggy’s hand, and makes his exit.

And that’s just Act I, roughly the first fifteen minutes, an admirably efficient piece of film making requiring about half the time it would take a Columbo episode to relate.

Enter Frank Cannon, an old friend of Peggy’s and an ex-cop turned PI. As usual, all of this circumstantial evidence is solidly against her, and she’s languishing in jail as a guest of the county. It’s fairly obvious clearing Peggy is going to be a tough job.

Unlike many Cannon episodes, which suffer from a lot of filler — usually in the form of car crashes, gun fights, helicopter chases, and so forth — “Murder by Proxy” shows its protagonist in full detective mode, with any attempt to terminate our hero left to the next-to-last scene.

Cannon’s investigation has, as Freeman indicated, “the effect of new matter.” That moved lamp, for instance: Cannon notes the markings on the rug and the lamp’s removal and correctly concludes how it was used to establish an alibi for the killer(s), as well as to exploit Peggy’s well-known temper.

He finds fragments on the rug in the foyer and, using a chair, locates that easily overlooked suction cup in the skylight (the police forensics was pretty sloppy in this case, nevertheless), and reasons out its connection to the floor lamp, as well as just how the cassette player figured in all this.

And for Ellery Queen fans, there’s even a dying clue.

About the cast: William Conrad (1920-94) starred in 121 episodes of Cannon, 14 installments of the short-lived Nero Wolfe (1981), and 104 episodes of Jake and the Fatman (1987-92).

Anne Francis (1930-2011) featured in 30 episodes of Honey West; she also gave a superb performance in the Twilight Zone installment “The After Hours” (1960).

Linden Chiles (born 1933) specializes in character parts; he appeared in four episodes of Banacek as the frazzled insurance company executive.

The director, Robert Douglas (1909-99), was a worthy successor to Basil Rathbone as a Hollywood villain (59 titles to his credit); he also directed mostly TV (39 titles), including Surfside 6 (7 episodes), 77 Sunset Strip (12), The Alfred Hitchcock Hour (4), Adam-12 (6), Cannon (5), The F.B.I. (13), The Streets of San Francisco (4), Baretta (9), Future Cop (2), and one Columbo (“Old Fashioned Murder,” 1976).

« Previous Page — Next Page »