May 2012

Monthly Archive

Thu 10 May 2012

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

During the last months of World War II the editors of Esquire decided to launch a series of short detective stories and invited various mystery writers to create new characters for possible publication in the magazine.

Among the invitees was Harry Stephen Keeler (1890-1967), perhaps the nuttiest author on earth. Harry got miffed at the thought of being asked to “submit a sample like a guy with a tin cup†and demanded $100 in advance. He must have fallen on the floor in shock when Esquire immediately sent him a check, although the editors specified that the advance wasn’t a commitment to accept his submission.

Keeler proceeded to string together a 14,000-word adventure about a barking clock and an astigmatic witness, with a 7½-foot-tall mathematically educated hick from the sticks serving as detective. At first the character was named just that — Abner Hick to be precise — but before sending out the manuscript Keeler prudently changed his name to Quiribus Brown.

When Esquire rejected the story, Keeler yanked Quiribus out of the plot, replaced him with that bedraggled old universal genius Tuddleton T. Trotter (who had starred in Harry’s mammoth extravaganza The Matilda Hunter Murder back in 1931), and added 85,000 more words to the story.

His Spanish publisher Instituto Editorial Reus issued the result as El Caso del Reloj Ladrador (1947). Keeler’s U.S. publisher, the bottom-rung Phoenix Press, put out a shorter version that same year as The Case of the Barking Clock.

Since Phoenix dropped Keeler in 1948, leaving him without a U.S. publisher for the rest of his life, Quiribus never saw the light of print in his native land. But Harry made him the protagonist in The Case of the Murdered Mathematician, issued in 1949 by his London publisher Ward, Lock.

So what new detective was chosen to grace the pages of Esquire? A New York PI named Peter Chambers whose creator was Henry Kane, a lawyer and something of a Chandler wannabee. Chambers narrates his own cases in an idiom, known to connoisseurs as High Kanese, which is worlds removed from Keeler’s style but just as lovably eccentric.

The first six Chambers stories appeared in Esquire between March 1947 and June 1948 and were collected as Report for a Corpse (Simon & Schuster, 1948).

The timing was unfortunate in the sense that the book came out several months after Anthony Boucher was let go as reviewer for the San Francisco Chronicle and before he became mystery critic of the New York Times. I’d love to know what Boucher thought of this volume, but it was his predecessor Isaac Anderson who reviewed the book in the Times.

I read the tales a few decades ago but had forgotten them completely when I started to reread them earlier this year. They’re more cleverly plotted than most PI stories during the years Chandler dominated the genre, but there’s nothing truly memorable about any of them and the narration is a pale shadow of what would soon become mature Kanese.

According to just about any print or electronic source you might check, Henry Kane was born in 1918 and is still alive. Apparently neither of these statements is true.

Lawrence Block had several conversations with Kane in the early 1970s and, while preparing a memoir of him for Mystery Scene, did some investigative work that was worthy of his own PI Matthew Scudder. An old girlfriend of Kane’s told Block that “he was most likely born not in 1918 but in 1908.†At least when Block knew him, he “lived on Long Island — Lido Beach, if memory serves — and spent Monday through Friday in an apartment on 34th Street west of Ninth Avenue.â€

Block tells us that he “took his work seriously, and insisted that each page be perfectly typed before he went on to the next one.†He was of Jewish descent but told Block that he “didn’t believe in any of that mumbo-jumbo.â€

His lifestyle was that of the stereotypical PI: a Dexedrine pill every morning, at least a quart of Scotch and a couple of packs of cigarettes a day. “It must have been sometime in the early ’80s that he died,†Block surmises.

Of the eleven Henry Kanes listed in the Social Security Death Index, the one who was born in 1908 and died in 1988 is most likely our man. I would love to have met him, though not necessarily in that smoke-choked apartment.

In his years as conductor of the “Criminals at Large” column for the Times, Anthony Boucher reviewed most of the Kane novels and collections, even though they were published in the unprestigious paperback-original format.

I still recall vividly the time he reviewed one of those novels twice. Its U.S. title was Too French and Too Deadly (Avon pb #672, 1955). In his Times column for December 18, 1955 he called the book “probably enjoyable; Peter Chambers stories are usually amusing, and this one is said to include ‘a locked room within a locked room.’

“But the publishers have chosen to crowd a full-length novel into 122 pages by squeezing 500 words onto a 4-inch by 6-inch page; and squinting one’s way through the book is too much to ask of a reviewer, a reader, or anyone save possibly a Lord’s-Prayer-on-Pinhead engraver.â€

Apparently Kane then sent Boucher a copy of the hardcover British edition, The Narrowing Lust (Boardman, 1956). In his column for June 24, 1956, Boucher reported that “now that it’s legible, it’s also highly readable†and “includes an unusually impossible-seeming locked room problem. It’s a welcome blend of strict detective puzzle and crisp and sexy thriller….â€

In my last column I quoted the late Fred Steiner, composer of the Perry Mason theme: “You look at those old film noir pictures, they’ve always got jazz going for some reason or other.â€

Since then I’ve discovered that this seems to be a classic case of false memory. The point was demonstrated by David Butler in his book Jazz Noir: Listening to Music from Phantom Lady to The Last Seduction (Praeger, 2002) and confirmed by William Luhr in his just published Film Noir (Wiley-Blackwell, 2012):

“Although many neo-noir movies have used single-instrument jazz solos to evoke the film noir era, it is difficult to find a canonical film noir [i.e. one that dates from the Forties or Fifties] that opens in that way. Most used full orchestral scores, as was standard studio practice.â€

It’s only in TV private-eye series like Peter Gunn that jazz became the norm. And, as Lawrence Block points out, the strongest uncredited influence on that landmark series was the novels and stories of Henry Kane — who wound up writing the Peter Gunn tie-in novel (Dell pb #B155, 1960)!

Is this a weird world or what? Luhr’s book is one of the few that discusses in depth both canonical noir and the more recent evocations of the genre, of which perhaps the finest is Chinatown (1974). I recommend it highly to anyone invested in that type of film. And aren’t we all?

Previously on this blog:

A Corpse for Christmas, by Henry Kane. Reviewed by Bill Deeck.

Trinity in Violence, by Henry Kane. A 1001 Midnights review by Art Scott.

The Midnight Man, by Henry Kane. A 1001 Midnights review by Bill Pronzini.

A Corpse for Christmas, by Henry Kane. Reviewed by Steve Lewis.

Until You Are Dead, by Henry Kane. Reviewed by Steve Lewis.

A long quote from the latter book is included as a big chunk of the review.

Tue 8 May 2012

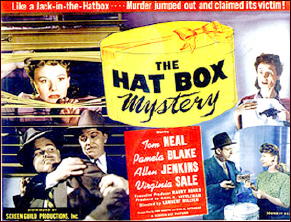

THE HAT BOX MYSTERY. Screen Art Pictures, 1947. Tom Neal, Pamela Blake, Allen Jenkins, Virginia Sale. Director: Lambert Hillyer.

There are a few remarkable things about this 45 minute movie, and the first is that it is a 45 minute movie, obviously the quick second half of a double feature on a Saturday matinee. The second remarkable thing is the opening scene, in which the four above-mentioned actors introduce themselves to the viewing audience and the characters they play. I’ll get back to that in a minute.

One other remarkable thing, at least to me, is that this movie was produced and appeared in 1947. While watching it, I was assuming all way through that it was a much earlier film, one from perhaps around the time that Chester Morris was beginning his run of Boston Blackie pictures (1941), but no. It must have been the story line, which is straight from the budget B-mystery movies of the even earlier 1930s.

Tom Neal plays private eye Rush Ashton, while Pamela Blake is his girl friend, secretary and assistant, Susan Hart. Allen Jenkins is “Harvard,” no last name given as I recall, is Ashton’s second-in-command, strangely enough, since “Harvard,” unable to get into Yale, seems barely able to steer himself across the street, where his girl friend Veronica Hoopler (Virginia Sale) owns and operates a hamburger joint.

Not too surprisingly, it is only Miss Hoopler who has any common business sense, as it is from her that Ashton’s struggling PI agency must keep borrowing money to keep afloat. You must have come to the thought by now that at least half of this movie is played as a comedy, and if I’d kept track, I’d be willing to say that you are correct.

Here’s the mystery portion: While Ashton is out of town on another case, a man in obvious disguise (glasses, phoney goatee) hires Susan to take his wife’s photograph with a camera disguised in turn as a hat box.

Little does Susan know, but happily accepting the man’s thirty dollars, that inside the hat box is not a camera, but a gun.

I’ll not say more. But surprisingly enough, Ashton does do some detective work in the case, the D.A. not being all that unfriendly, and the story is not a total disaster. If the script had been been revised so that the clues could have incorporated more into the story, instead of lumped into one great expository dump at the end — more viewers probably having figured it all out on their own anyway — this movie might have been — a contender? No, but something better than the (in all likelihood) throwaway second half of a double feature.

Also surprisingly enough, the four players got to play the same roles all over again the following month, in a follow-up film titled The Case of the Baby-Sitter. While The Hat Box Mystery is readily available on DVD, copies of the second movie do not seem to exist, although one reviewer on IMDB must have seen it, as he complains in passing that Allen Jenkins may have gotten more screen time than Tom Neal.

That’s rather discouraging news, but if a copy came along, would I watch? I don’t know what this says about me, but you bet I would.

[UPDATE] 05-08-12. This review was first posted on this blog on May 30, 2008. I’ve bumped it up in time because a lively discussion has been taking place in the comments section over the last day or so. Not only has the conversation been lively, but it’s also been very informative. I thought the rest of you might like to know about it, rather than keep it buried, as it were, nearly four years in the past. I’ve altered and (hopefully) improved the selection of images, too.

Tue 8 May 2012

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

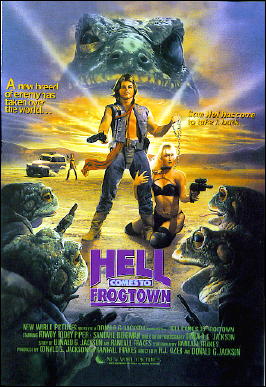

HELL COMES TO FROGTOWN. New World Pictures, 1988. Julius LeFlore, RCB, Roddy Piper, William Smith, Sandahl Bergman, Kristi Somers, Rory Calhoun, Cliff Bemis. Directors: Donald G. Jackson & R. J. Kizer.

[After watching those early Rory Calhoun action westerns], small wonder that I broke down and shelled out the $10 necessary to own my own copy of Donald G. Jackson’s 1988 cult classic Hell Comes to Frogtown.

The World really needed a post-apocalypse movie with a sense of humor and this is it, a clever, relentlessly trivial thing about the end of Life as We Know It and What Happens Next.

Writer/Director Jackson manages to avoid most of the cliches inherent in the concept of a Future Society Ruled by Women, gets surprisingly not-awful performances from Sandahl Bergman and pro wrestler “Rowdy” Roddy Piper, and even manages to evoke a lot of sympathy for a washed-up amphibian chanteuse played, I think, by Shirley Maclaine in heavy makeup and an unbilled cameo.

Rory Calhoun, needless to say, is just fine as a garrulous old prospector named “Looney” Tunes, and one of the fight scenes between Piper and a six-foot talking toad brought down the House (such as it was) when Piper called his warty opponent a “horny bastard.” Priceless.

Editorial Comments: The trailer for this film can be seen here on YouTube. For a scene entitled “The Dance of the Three Snakes,” go here.

Mon 7 May 2012

DAVID GOODIS vs. THE FUGITIVE

by Francis M. Nevins

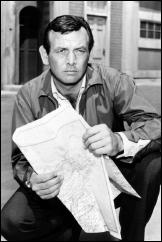

In the last few years of David Goodis’ life, one of the most popular TV series was ABC’s The Fugitive, the saga of Dr. Richard Kimble (David Janssen) who was wrongly convicted of his wife’s murder, escaped from the wreck of a prison-bound train, and spent the next several years on the run, criss-crossing the country, changing identities constantly, being stalked relentlessly by the Javert-like Lt. Gerard (Barry Morse) as he searched for the one-armed man who was the real murderer.

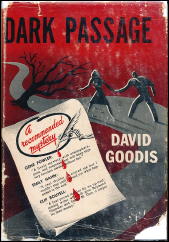

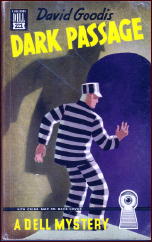

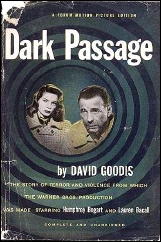

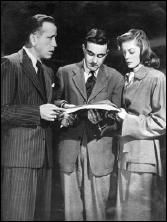

The series was produced by United Artists Television and ran on ABC for four seasons (1963-67) and 120 hour-long episodes. A year or so into its run, Goodis became convinced that the series was a rip-off of his own first crime-suspense novel, Dark Passage (1946), which had been serialized in the Saturday Evening Post before book publication and, a year later, became the basis of a Warner Brothers movie starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall.

Both the novel and the movie told the story of Vincent Parry, who was not a doctor but did escape from prison after being wrongly convicted of his wife’s murder and, although never stalked by a cop, did set out to clear himself and find the real killer, who was not a one-armed man.

Goodis’ suit against United Artists TV raised three interesting legal issues. The one we’ll address first and last was whether The Fugitive infringed the copyright in Goodis’ novel. The Copyright Act of 1909, which was the governing law throughout Goodis’ lifetime, says that the owner of a copyrighted work has the exclusive right to “copy†the work. (The operative verb in the present Copyright Act is “reproduce.â€)

But neither statute sets any sort of standard for determining whether one work infringes another. What is that standard? Copyright law would be absurd and useless if it required absolute identity between the two: otherwise I could rip off The Da Vinci Code simply by changing the hero’s name to Langbert Robdon.

But the law would be equally absurd, and contrary to public policy and probably to the First Amendment also, if it allowed authors to claim copyright protection for the ideas in their works, so that, for example, the first person who wrote a novel or story about an intelligent dignified black detective could sue anybody else who later did the same thing.

In order to avoid both these extremes, the judicial decisions interpreting the Copyright Act have required for generations that in order to win an infringement suit a plaintiff has to establish that his work and the defendant’s work are “substantially similar†on the layer or level not of abstract ideas but of concrete expression.

The problem of course is that the line separating ideas from the expression of ideas is indefinable. But in order to prevail in an infringement suit the plaintiff has to establish substantial similarity on the expression side of that indefinable line. This is what Goodis set out to do when he sued over The Fugitive.

During the litigation the defendants took Goodis’ deposition, and their attorney questioned him intensely about what common elements he found between Dark Passage and The Fugitive. A few years ago, at a conference in Philadelphia, the law firm that had represented Goodis gave a presentation about the case. I was supposed to be there but missed my train.

Some kind soul knew of my interest and saved me a copy of Goodis’ deposition, which was handed out to those who attended. I decided that, shorn of side issues and redundancies, this document would make a good teaching tool in my Copyright Law course because it illustrates so vividly how the game is played.

Goodis, obviously well coached by his lawyers, tries to make the similarities seem as concrete as possible while the defense team tries just as hard to reduce them to abstract ideas. Let’s travel back in time and eavesdrop:

You say that you have seen some 20 to 25 … episodes of

The Fugitive, is that correct?

Yes, possibly more, but that would be a minimum, yes.

Based upon your familiarity with Dark Passage and that stated familiarity with The Fugitive, what similarities with respect to ideas do you see, if any, between the two works?

…[T]he nucleus of the plot is exactly the same… In Dark Passage, the entire story is based upon a situation involving a man who has been unjustly sentenced for the murder of his wife. Subsequently he…escapes from prison and seeks to find the murderer but through a series of unfortunate circumstances he is forced to keep running… [I]n the course of his escape … the protagonist, Vincent Parry, is aided by a young woman named Irene Janney who is present at the courtroom proceedings and who believes in his innocence. In a particular segment of The Fugitive … the protagonist, Richard Kimble, is aided by a young woman [played by] Suzanne Pleshette who is present at the courtroom proceedings wherein Kimble was found guilty and sentenced and who believes in his innocence….

Please continue with respect to any ideas that you found to be similar between Dark Passage and … The Fugitive.

Now in Dark Passage the protagonist, Vincent Parry, is portrayed as a mild-mannered man who is not bitter against society as a result of being unjustly condemned but who, when the situation demands it, is capable of great valor … and physical strength…. [T]he protagonist of The Fugitive, Richard Kimble, is portrayed in essentially the same light. Next point: In the course of his fleeing, Vincent Parry assumes disguise, physical disguise.

That is by having plastic surgery performed on his face, is it not?

That is correct, sir.

Continue, please.

In the course of his fleeing in this same connection, Richard Kimble in The Fugitive assumes disguise.

What type of disguise?

By having his hair dyed, by dyeing his hair. Next point: In Dark Passage the protagonist, Vincent Parry, confronts the actual murderer of his wife but is unable to use her confession to absolve himself inasmuch as the murderess falls out of a window to her death. In The Fugitive the protagonist, Richard Kimble, confronts the actual murderer … but is unable to use the murderer’s confession inasmuch as the murderer … gets away before the police arrive.

Was that particular [episode of The Fugitive] the same one to which you referred earlier as featuring Suzanne Pleshette?

No, sir…..

Please continue.

In the novel and film Dark Passage, Vincent Parry … is aided in the course of his escape by a somewhat offbeat taxi driver whose philosophy is somewhat cynical. In the same connection, in various segments of The Fugitive, the protagonist Richard Kimble is aided by various offbeat characters whose philosophies are somewhat cynical and at times world-weary.

Were any of them cab drivers?

Not to my recollection.

Go ahead.

In the novel and film Dark Passage, Vincent Parry in the course of his escape is harassed by a character [named Arbogast but] … who attempts to utilize Parry’s predicament for his own selfish motives … a form of blackmail…. In the same connection, in various [episodes] of The Fugitive Richard Kimble in the course of his fleeing is harassed by various individuals who attempt to utilize his predicament for their own selfish motives.

Did any of them attempt blackmail or extortion, do you recall?

To the best of my memory, these motives included various forms of monetary gain. I can’t tell you truthfully whether blackmail was utilized per se. I can’t remember.

In Dark Passage the fellow named Arbogast has followed Parry almost from the time of his escape up to the time of their final confrontation in the book…, where they meet in a hotel room and have their final confrontation which takes place there and subsequently in Arbogast’s car. Is that correct?

That is correct.

In The Fugitive series is there any one character who is continually following the protagonist, as you call him, Richard Kimble?

Yes. [There are] many, many instances where characters who attempt to use Kimble’s predicament for their own selfish gains… follow him.

[I]sn’t there one particular character in The Fugitive who is continually following Richard Kimble?

Not in that connection, not in the connection of utilizing Kimble’s predicament for his own selfish motives, no.

Is there any character, regardless of his motives, that is continually following Richard Kimble in The Fugitive series?

Yes… That is a detective….

Will you please continue with your comparison of ideas.

….I noticed in watching various [episodes] of The Fugitive similarity in characterization of the protagonist based mainly on the fact that the protagonist in Dark Passage is a man who…thinks of others before he thinks of himself and because of this is constantly falling into jeopardy….[I]n many, many segments of The Fugitive, the protagonist Richard Kimble is portrayed as a man who thinks of others before he thinks of himself and because of this is constantly falling into jeopardy.

Later in the deposition, obviously reading from notes, Goodis summarized the alleged similarities between his novel and the TV series.

(1) In Dark Passage Parry is primarily motivated by his determination to discover the truth concerning the murderer of his wife and the identity of the murderer. In The Fugitive Kimble is primarily motivated by his determination to discover the truth concerning the murderer of his wife and the identity of the murderer….

(2) In Dark Passage Parry is described as a man who is not especially aggressive or physically powerful but he is equal to the occasion when threatened with physical violence. In The Fugitive Kimble is portrayed as a man who is not especially aggressive or physically powerful but he is equal to the occasion when threatened with violence….

(3) In Dark Passage Parry is portrayed as a quiet-spoken, reserved type, sensitive and kindly, considerate of others and with high standards of moral behavior. In The Fugitive Kimble is portrayed as a quiet-spoken, reserved type, sensitive and kindly, considerate of others and with high standards of moral behavior….

(4) The treatment of Dark Passage places emphasis on Parry’s panic and fear of being apprehended before he can find the murderer of his wife rather than his bitterness at being unjustly accused and condemned. The treatment of The Fugitive places emphasis on Kimble’s panic and fear of being apprehended before he can find the murderer of his wife rather than his bitterness at being unjustly accused and condemned….

(5) In Dark Passage Parry is forced by circumstances to live and behave like a hunted animal. He can trust no one, not even those who want to help him. The treatment of the novel … places considerable emphasis on this aspect of the story. In The Fugitive Kimble is forced by circumstances to live and behave like a hunted animal. He can trust no one, not even those who want to help him. The treatment of the television series places considerable emphasis on this aspect of the story…

(6) In Dark Passage Parry is portrayed as a man whose “lips are not made for smiling,†a man whose eyes reflect a sadness caused by his loneliness and his awareness of the unpredictable tides of fate. In The Fugitive Kimble is portrayed as an unsmiling, sad-faced man, whose eyes reflect a certain sorrow caused by his loneliness and his awareness of the odds imposed by the unpredictable hand of fate….

(7) In Dark Passage Parry’s actual escape from prison is merely a prologue for the ensuing events. The story itself is treated from the standpoint of the hazards facing an innocent man who must keep running and hiding while at the same time seeking the means to eventually prove his innocence. In the same connection, in The Fugitive the entire series is based on a montage used in various segments as a prologue for the ensuing events. This prologue, accompanied by the voice of a narrator, depicts the escape of an innocent man and is of course the springboard for the episode that follows. Regardless of the content of the segment, the plot and theme of the entire series are based on the hazards facing an innocent man who must keep running and hiding while at the same time seeking the means to eventually prove his innocence…

[W]hat is the theme of

Dark Passage?

…The theme of Dark Passage involves the plight of an innocent man condemned for the murder of his wife, constantly on the run after having escaped from the authorities, aided by those who sympathize with him and menaced by others who are motivated by their own selfish interests.

What do you understand…to be the theme of [The Fugitive]?

Essentially the same….

What is the plot of Dark Passage as you understand it?

…[A]n innocent man condemned to life imprisonment for the murder of his wife escapes from prison and is aided by those sympathizing with him and menaced by others who are motivated by their own selfish interests.

What did you consider to be the plot of The Fugitive … to the extent that you found one?….

The same thing, essentially the same.

The defendants made a motion for summary judgment, asking the court to throw out the suit purely on legal grounds, but it wasn’t based on any claim that as a matter of law Dark Passage and The Fugitive were not substantially similar.

In effect UA TV took the position: “Assuming for the sake of the argument that we did take substantial material from Dark Passage, we were legally entitled to do so.â€

The first of the two legal arguments they offered was based on the 1945 contract by which Goodis for $25,000 sold Warner Bros. the movie rights in his novel. Like most such contracts in Hollywood’s golden age, this one included language permitting the studio not only to make a movie based on the novel but to remake it as often as the studio chose. United Artists TV claimed that The Fugitive was legal on the basis of those remake rights, which it had bought from Warners.

Could the contractual language have been broad enough to justify such a claim? Could a clause primarily intended to authorize one or at most a handful of theatrical remakes be stretched to justify the making of a TV series that lasted for 120 hour-long episodes?

The federal district court hearing the case ruled that it not only could be but was, and on January 2, 1968, almost a year after Goodis’ death, granted summary judgment to the defendants on that basis, quoting from the 1945 contract at great length. Anyone who wants to go to a law library and read the decision will find it in Volume 278 of the Federal Supplement, beginning at page 120.

The defendants’ second legal argument grew out of the Goodis deposition. Apparently the UA TV attorneys hadn’t previously realized that the Saturday Evening Post had paid Goodis $12,000 for the right to publish Dark Passage in six weekly installments before its publication in book form.

Unfortunately the only copyright notice in those six issues of the Post was the general notice on the table of contents page in the name of the Curtis Publishing Company. But Curtis wasn’t the copyright owner of Dark Passage; it was merely the licensee of magazine serialization rights from Goodis, the real copyright owner.

Therefore, the defendants argued, Dark Passage had been published serially without a proper copyright notice, with the consequence that it had been in the public domain ever since and anyone could make any use of it that they pleased.

This may sound to 21st-century ears like an argument worthy of Alice in Wonderland or Catch-22, but under the 1909 Copyright Act, which was in force at the time of this case and remained the law until the beginning of 1978, it was a sound contention, and the District Court granted UA TV’s motion for summary judgment for that reason also. The Goodis estate appealed both rulings.

The case moved through the legal system like a frozen snail. It took more than two years for the Second Circuit Court of Appeals to hand down its decision, but from the viewpoint of Goodis’ successors it was worth waiting for.

In Goodis v. United Artists Television, which was dated March 9, 1970 and can be found in Volume 425 of the Federal Reporter, Second Series, beginning at page 397, the appeals court reversed the trial judge on both grounds.

All three appellate judges sitting on the panel — Kaufman, Lumbard and Waterman — agreed, in Chief Judge Lumbard’s words, that “where a magazine has purchased the right of first publication under circumstances which show that the author has no intention to donate his work to the public, copyright notice in the magazine’s name is sufficient to obtain a valid copyright on behalf of the beneficial owner, the author or proprietor.â€

The court’s refusal to impose Draconian consequences on an author because of a minor defect in a copyright notice constituted a landmark decision at the time, and the law has continued to evolve in the same direction ever since. Indeed under our present Copyright Act no notice at all is necessary in order for a work to be protected.

On the question of interpreting the contract between Goodis and Warners the three appellate judges split. Lumbard would have upheld the district court’s grant of summary judgment but was outvoted by Kaufman and Waterman.

“The question presented here,†Waterman wrote, “is whether the contract language demonstrates unambiguously that Goodis meant to convey to Warner Brothers the right to create a television series such as The Fugitive or whether a genuine issue of material fact exists as to what the parties intended by the language they used… It is our holding that the contract language does not so clearly permit production of The Fugitive as to entitle the defendant to a grant of summary judgment.â€

This too constituted a major improvement in authors’ rights. Thanks to the court’s refusal to hold as a matter of law that the contract between Goodis and Warner Bros. conveyed extremely broad rights as UA contended, it would be up to a jury to decide that issue if and when the case came to trial.

That trial never took place. After the Second Circuit decision the defendants paid Goodis’ successors a small amount of money to drop the suit and go away. But since UA TV had never admitted any substantial taking from Dark Passage, at trial Goodis would still have needed to show substantial similarity between his novel and The Fugitive.

Could he have done so? I’ve read the novel and seen the movie based on it, and 40-plus years ago I watched The Fugitive TV series regularly. I’ve also taught copyright law for almost 40 years and written some crime-suspense fiction of my own, and of course I’ve read Goodis’ deposition several times.

My tendency is to demand a strong showing before I find two works substantially similar, so perhaps I’m a bit prejudiced. But Goodis’ case strikes me as very weak, so weak that the trial court might well have refused to allow a jury even to consider the issue, on the ground that no reasonable jury could have decided in Goodis’ favor on the evidence he presented.

We’ll never know. A lawsuit is like a horse race: anything can happen. One of the great lawyerly virtues is prudence. It was prudent of UA TV to offer a settlement and prudent of the Goodis successors to accept it.

We also cannot know whether Goodis himself would have accepted a settlement had he lived. But if there’s an afterlife and they serve liquor, he no doubt would have toasted the wisdom of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in using his case to strike two blows on behalf of all authors living and dead.

Sun 6 May 2012

REVIEWED BY MICHAEL SHONK

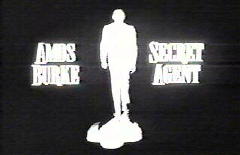

AMOS BURKE, SECRET AGENT. ABC / Four Star Productions / Barbety, 1965-66. Cast: Gene Barry as Amos Burke, Carl Benton Reid as The Man. Series based on characters created by Frank D. Gilroy. Produced by Aaron Spelling.

From Aaron Spelling: A Prime Time Life, by Aaron Spelling with Jefferson Graham: “Burke’s Law was one of my first great campy shows… Then ABC threw us a curveball with the ‘James Bond’ craze. Suddenly secret agents were in… So in 1965 Burke’s Law, the story of a millionaire L.A. detective, was forcibly changed to Amos Burke, Secret Agent. He became a debonair, globe-trotting secret agent for a United States intelligence agency. I hated it, Gene hated it, we all hated it, and ABC was very wrong to change it…â€

The series was a ratings failure from the very beginning. “Balance of Terror†(9/15/65) was the series first episode. The Arbitron ratings (Broadcasting, 9/20/65) found NBC’s I Spy at 37.6 share (first half hour) and 40.9 (last half hour) compared to CBS’s Danny Kaye at 32.3 share and 30.3 share compared to Amos Burke at 24.8 share and 25.8 share. By November the series would be cancelled (Broadcasting, 11/1/65).

Interestingly, the final episode of the series, “Terror in Tiny Town, Part Two” aired at 10pm on Wednesday, January 12, 1966, the same night ABC premiered its new spy series Blue Light at 8:30pm. Could the failure of Amos Burke have played a role in ABC picking up Blue Light and the rush to get it on the air?

So besides the audience having little interest in Amos Burke as a spy, and everyone involved hating it, the series also had a fatal creative flaw, The Man.

The Man was supposed to be Amos Burke’s “M” (Bond) or Mr. Waverly (Man from U.N.C.L.E.). Instead The Man was one of the most unlikable, heartless, mean characters ever to play a good guy on TV. While Amos could not contact The Man, The Man gave him a watch that when it buzzed, it meant Amos had to stop everything and get to the airport as fast as possible to meet The Man. The Man’s office was the inside of a DC-9 and he conducted all meetings (but one) in the air.

Amos would wait on the landing strip in his Rolls (the only other surviving character from Burke’s Law) for The Man’s plane. Once it landed, Amos would pull out what looked like a sonic pen light and point it at the plane, the sound would lower the stairs and Amos would enter and cool his heels in the outer “office†until The Man gave him permission to enter. Then Amos would use the door’s keypad (with comical beeps and boops) to open the door. This is how sidekicks get treated, not the hero.

Most episodes featured at least one beautiful woman on each side. Amos enjoyed working with women, and while much of his dialog sounds condescending today, he treated his female contacts as equals. But for Amos, women were usually interchangeable. In one episode (I won’t spoil it by naming it) Amos’s contact is a beautiful intelligent woman Amos admires, but after her death in action he doesn’t even comment on the loss. At the end, he seduces her replacement.

Production values were on the cheap side and sets and exteriors were noticeably recycled week after week. But Supervising Art Director Bill Ross and his crew did a creative job using sets to establish the style of the show, with campy odd shaped doors for the villain’s lair to menacing underground dungeons.

While few miss Amos Burke, Secret Agent, one wonders why ABC cancelled the series instead of returning to the successful police formula of Burke’s Law.

EPISODE GUIDE —

“Balance of Terror.” September 15, 1965. Writtenby Robert Buckner. Director: Murray Golden. Guest Cast: Will Kuluva, Gerald Mohr, Michele Carey * Amos takes the place of an arrested courier for a group smuggling gold from Red China into Latin America. (Part of the opening of this episode can be seen here on YouTube.)

“Operation Long Shadow.” September 22, 1965. Written by Albert Beich & William H. Wright. Director: Don Taylor. Guest Cast: Antoinette Bower, Dan Tobin, Rosemary DeCamp * A kidnapping of the son of an Algerian government official is the key to a mysterious plot. The “B†storyline involved two vacationing American tourists who knew Amos as the good guy detective and Amos proving to them he has turned into a spoiled playboy cad. In one of the more imaginative death traps of the series, Amos is locked in a moving train car filling up with gas. He escapes with the aid of the air in his Rolls tires.

“Steam Heat.” September 29, 1965. Written by Marc Brandel. Director: Virgil Vogel. Guest Cast: Nehemiah Persoff, James Best, Jane Walo * Exiled Mob boss mixes business with revenge when he plans to kill the Senator who got him kicked out of the country while his gang robs New York City using a knockout gas released through the city’s steam pipes. In this episode Amos receives instructions with breakfast on a record disguised as a flapjack.

“Password to Death.” October 6, 1965. Written by Marc Brandel. Director: Seymour Robbie. Guest Cast: Janette Scott, Joseph Ruskin, Michael Pate * A dying clue ‘S Day’ leads Amos to Cornwall, England and an evil villain. One of the best episodes of the series as it featured the perfect spy plot for the series premise. It also had my favorite line of the series. After quoting Shakespeare, Amos adds “Hamlet’s Law.†(It is Janette Scott seen with Gene Barry in the two photos above and to the right.)

“The Man with the Power.” October 13, 1965. Written by Stuart Jerome. Director: Murray Golden. Guest Cast: Thomas Gomez, John Abbott, Ilze Taurins * Amos’s attempt to help a scientist defect goes wrong, leaving the unconscious scientist wired to a bomb. The Man worries about America’s image as Vienna is evacuated.

“Nightmare in the Sun.” October 20, 1965. Written by Tony Barrett. Director: James Goldstone. Guest Cast: Barbara Luna, Edward Asner, Joan Staley, Elisha Cook * The Man is concerned about an assassination attempt of a Mexican Government official by two Americans because it might prevent the approval of a treaty between America and Mexico. Flawed by its predictability and many moments that make little to no sense.

“The Prisoner of Mr. Sin.” October 27, 1965. Teleplay: Gilbert Ralston and Marc Brandel. Story: Gilbert Ralston. Director: John Peyser. Guest Cast: Michael Dunn, France Nuyen, Greta Chi * Code breaking genius Waldo Bannister is replaced by a machine, rather than find something else for his “brilliant brain†to do, the American government places him under house arrest for a year. When he escapes, Amos is assigned to find Waldo. The trail leads to ruthless mercenary Indian (Michael Dunn) who ‘helps’ people on the run then sells their secrets and drains their bank accounts.

“Peace, It’s a Gasser.” November 3, 1965. Written by Palmer Thompson. Director: James Goldstone. Guest Cast: Henry Jones, Ruta Lee. Brooke Bundy * Evil Mastermind demands the end of war or he will use his gas that turns adults into self-obsessed children. His minions are teenagers who, all but one, are willing to kill for peace. This episode got dumber with every twist. In one scene The Man taunted Amos for going soft when Amos objected to The Man using him as an executioner of one of the agency’s own men.

“The Weapon.” November 10, 1965. (not viewed)

“Deadlier Than the Male.” November 17, 1965. (not viewed)

“Whatever Happened to Adriana, and Why Won’t She Stay Dead?” December 1, 1965. Written by Warren Duff. Director: Seymore Robbie. Guest Cast: Albert Paulsen, Jocelyn Lane, Joan Patrick * A drug dealer attempts to smuggle missiles into Latin America. Flawed by a weak villain (who runs at any hint of danger) and twists that needed to be treated more seriously.

“The Man’s Men.” December 8, 1965. Written by Albert Beich & William H. Wright. Director: Jerry Hopper. Guest Cast: Nancy Gates, Vaughn Taylor, Norman Alden * Bad guys break into MX3’s cover station, the American Bison Society, and steal a list of the agency’s agents. Great visual clue, shown more than once, that is harder to notice than figure out who done it. Gadget of the week featured a safe that when broken into lets out a radioactive gas that makes the back of the thieves’ ears glow.

“Or No Tomorrow.” December 15, 1965. Written by John & Ward Hawkins. Director: Virgil Vogel. Guest Cast: Abbe Lane, Lee Bergere, Ziva Rodann * Spoiled Prince gets his hands on a fungus that could destroy the world’s rice crop. He wants the U.S. to turn over two spies they have in prison so he can sell their secrets. Filled with pointless scenes like a William Tell contest between Amos and the Prince. Dumbest opening in series, Amos is greeted with a bomb in his room. His cover blown, Amos continues on the case with a bad guy following him to Amos’s local contacts.

“A Little Gift for Cairo.” December 22, 1965. (not viewed)

“A Very Important Russian Is Missing.” December 20, 1965. Teleplay: Tony Barrett. Story: Samuel A. Peeples and Tony Barrett. Director: Virgil Vogel. Guest Cast: Phyllis Newman, Donald Harron, Nina Shipman * The Russians and Americans join forces to find a kidnapped Russian official before the Chinese can. Nice plot, twists, and sets but weaken by series campy premise.

“Terror in a Tiny Town.” Part One: January 5, 1966. Part Two: January 12, 1966. Written by Marc Brandel. Director: Murray Golden. Guest Cast: Robert Middleton, Kevin McCarthy, Lynn Loring * Brainwashed by local radio station, a town with Atomic research plant becomes violently paranoid about the threat of outside influences on their way of life. Heavy-handed morality tale against the evils of bigotry and the 50s “Red Scare.â€

Sun 6 May 2012

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

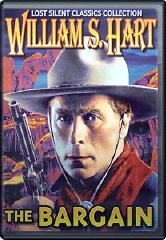

THE BARGAIN. New York Motion Picture Corp., 1914. William S. Hart, J. Frank Burke, Barney Sherry, James Dawley, Clara Williams, Charles Swickard, Roy Laidlaw, Herschel Mayall. Scenario by Thomas H. Ince and William H. Clifford; cinematography by Joseph H. August and/or Robert Newhard. Director: Reginald Barker. Shown at Cinevent 39, Columbus OH, May 2003.

Hart’s first feature-length film, The Bargain, as the program notes aptly pointed out, established the basic elements that would be a hallmark of the Hart Western (notably the concept of the good-bad man who is regenerated through his love for a good woman).

The film was shot in and near the Grand Canyon (with some sources claiming the cinematography was by Joseph August) and while the print was not always the sharpest, varying in quality from reel to reel, the Arizona landscape was captured in its startling beauty and awesome grandeur.

I was immediately struck by the opening sequence in which each of the cast members is first shown in evening attire, then as they bend over, hiding their face from the camera, they straighten up in makeup and costume for their on-screen-roles. (Dan Stumpf commented that he had seen this device used in at least one other Hart film.)

Hart plays outlaw Two-Gun Jim Stokes who, after he is wounded by a posse, is rescued by a farmer (J. Barney Sherry) who takes him to his shack, which he shares with his daughter Nell (Clara Williams).

Stokes and Nell fall in love, are married, and Stokes leaves to settle some unfinished business (he plans to return the money from his most recent holdup), promising to return.

He’s captured by Sheriff Bud Walsh (J. Frank Burke) but when Walsh, falling prey to temptation, gambles away the money he’s rescued from Stokes, Stokes strikes a bargain that will save Walsh’s reputation and allow Stokes to escape to a new life.

In a sense, The Bargain was Ince’s response to DeMille’s The Squaw Man. It made Hart a star and confirmed the Western as a major film genre.

Sat 5 May 2012

REVIEWED BY WALKER MARTIN:

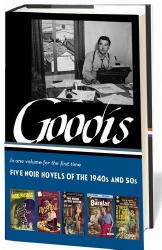

DAVID GOODIS – Five Noir Novels of the 1940’s and 1950’s. Library of America, hardcover, March 2012.

I’ve been reading and collecting books from The Library of America ever since they first started coming out. At first it looked like they would just be publishing the works of the established literary figures, great authors like Henry James, Eugene O’Neill, Mark Twain, Herman Melville, and so on.

But lately they have crossed over into more popular areas and genres by publishing two volumes of crime novels (including Down There by David Goodis), Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, H.P. Lovecraft, Philip K. Dick, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Kurt Vonnegut, two volumes titled American Fantastic Tales, and now David Goodis.

I see this as a very good sign for popular culture and the mystery and SF genres. I guess it is too much to hope for volumes dealing with great western fiction but seeing this volume on Goodis makes me hope that we will see collections by Jim Thompson, Peter Rabe, Charles Williams, John D. Macdonald, Ross Macdonald, Gil Brewer, and others.

We should not be surprised to see Goodis singled out for such attention because the French have long thought he was exceptional and in fact the only full length biography is in French. He was the poet of the bleak, doomed, and lost. It’s been said that Goodis did not write novels; he wrote suicide notes.

I first became aware of David Goodis back in the 1960’s when I started to collect the pulp magazines. His pulp career lasted from 1939 to about 1947. He has been quoted as saying that he produced millions of words for the sport, detective, and western pulps. But most of his work was published in what I call the air-war pulps. I eventually accumulated extensive runs of such titles as Fighting Aces, Battle Birds, RAF Wings, Dare-Devil Aces, and Sky Raiders. Goodis appeared in all these pulps with dozens of stories, perhaps over a hundred.

I would have to admit that I found his pulp work to be less than interesting. I’ve always had a problem with the air pulps with seemed to concentrate too much on airplanes and flying, while ignoring characterization and believable plots. I eventually sold, traded, and disposed of all my air-war magazines.

There is an excellent DVD dealing with Goodis’ life, marriage, and career called David Goodis … to a Pulp It’s a must for anyone interested in his writing and one of the extras points out that Goodis’ wife evidently felt the same way as I did concerning his pulp stories.

His wife told her second husband that the reason she left Goodis and divorced him was because she couldn’t stand his pulp writing that he was doing for the air-war magazines.

She must have received a shock when he broke into the slick market with his novel, Dark Passage for the Saturday Evening Post in 1946. Not only did he receive a far higher rate of pay than he was getting for his pulp work, but Hollywood paid $25,000 for the screen rights. In today’s money that is around a quarter of a million. The movie was not just your usual effort, but starred Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall.

At this time it was goodbye to the pulps and the beginning of his Hollywood career. Despite receiving good money he still wore threadbare suits and slept on the couch of a friend for $4.00 a month. He soon found himself out of a job and back in Philadelphia, living in his parents house, and writing original novels for such paperback firms as Gold Medal.

The Library of America edition reprints five complete novels. All five were made into interesting movies. and my comments on both the books and films follow:

â— Dark Passage. Though this is Goodis’ first real success, I don’t think it is an outstanding novel. My feeling on a second reading was that it is OK, good in spots by nothing that special.

The story is not too believable and suffers from the happy ending. It reminds me of Cornell Woolrich, only not as good. I find the plot absurd with the rich, pretty girl falling in love with the loser convicted of murder. Also ridiculous to think that a cab driver and doctor would help the hero without even knowing anything about him.

I watched the movie for the sixth time (I have a Bogart book which I annotate every time I see one of his films), and it’s hard to believe that they would cover up his face in bandages for most of the movie. But it does follow the plot of the novel and I find it better than the book.

â— Nightfall. This also is just OK but nothing that special. Another innocent man framed for murder and robbery. Both these novels have a silly scene where the hero gets the gun away from the criminal by distracting him with talk. And another beautiful girl.

Again I found the movie better than the book. It follows the basic plot with some changes but Aldo Ray is bland as the innocent man in trouble. Great villain.

â— The Burglar. I found this novel to be better than the two above. Instead of the typical innocent man wrongly accused plots, this one was more believable with a professional jewel thief becoming involved in killings. Very downbeat ending, just what you would expect from Goodis.

The movie stars Dan Duryea and Jayne Mansfield and follows the plot of the novel. The fact that David Goodis wrote the screenplay makes this even more interesting.

â— The Moon in the Gutter. With this book, it appears the novels are getting better. This one does not star a criminal or men framed for murder but has as a protagonist a laborer working on the docks and living in a slum area of Philly.

He hangs out in a dive called Dugan’s Den, which has the atmosphere and characters right out of a Eugene O’Neill play. Vernon Street in Philadelphia takes on a life of its own and becomes a character in the novel.

The movie was made in 1983 and is French with subtitles, starring Gerard Depardieu and Nastassia Kinski. It follows the basic plot of the novel.

â— Street of No Return. Mediocre and not too believable. Skid row bum and drunk (a former famous singer) defeats criminal plan to cause race riots. Dialog is poor and the police act like idiots. Another beautiful girl falls for our hero.

The movie was directed by Samuel Fuller and stars Keith Carradine. However in this case, the film was even more disappointing than the novel. Believe me, you don’t want to see Keith Carradine in a fright wig, trying to act like a bum.

Despite the critical comments above, I did enjoy reading the five novels but lucky for me after reading them I immediately spent some time at a book convention buying and reading pulps. Otherwise, I might have hanged myself. No wonder Goodis lived such a short life, from 1917 to 1967.

Bibliography (novels and story collections only)

Retreat from Oblivion, 1939.

Dark Passage, 1946.

Nightfall, 1947.

Behold This Woman, 1947.

Of Missing Persons, 1950.

Cassidy’s Girl, 1951.

Of Tender Sin, 1952.

Street of the Lost, 1952.

The Burglar, 1953.

The Moon in the Gutter, 1953.

Black Friday, 1954.

Street of No Return, 1954.

The Blonde on the Street Corner, 1954.

The Wounded and the Slain, 1955.

Down There (Shoot the Piano Player), 1956.

Fire in the Flesh, 1957.

Night Squad, 1961.

Somebody’s Done For, 1967.

Black Friday and Selected Stories, 2006. [A collection of his shorter work from such magazines as Ten Story Mystery, Colliers, New Detective, Manhunt and Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine.]

Thu 3 May 2012

REVIEWED BY GEOFF BRADLEY:

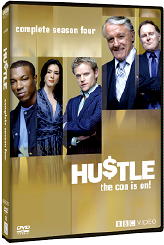

HUSTLE. BBC-TV, UK. Series Four: April 18 to May 23, 2007. (Seen on the American Movie Classics cable channel in US.) Marc Warren, Robert Glenister, Jaime Murray, Robert Vaughn, Rob Jarvis. Created by Tony Jordan.

Hustle has returned for a new series (the fourth: one hour each, no adverts) about the ‘lovable’ group of London conmen (one woman) who, of course, delight in fleecing those that deserve to be fleeced.

In the first episode we hear that leader Mickey Stone is pursuing a mark in Australia (actually actor Adrian Lester has left the series) and so the group go about pursuing an oil-rich Texan (played by Robert Wagner) by flying to Los Angeles and attempting to sell him the Hollywood sign.

These stories are, in general, quite enjoyable but the problem is that they tend to be very similar and we have already had 24 of them. This first tale, with its Californian setting, seems particularly unlikely, but then realism is not the aim.

The second story returns to England with a story involving passing a dud horse off as a high-flying racer and selling it to an upstart cockney millionaire. Very watchable, but you run the risk like with a box of chocolates of eating too many all at once — and you don’t want to look too closely at what’s gone into it.

Editorial Comments: This review was reprinted from Geoff’s apazine Caddish Thoughts #127, July 2007. The series has proved successful enough that four more seasons of episodes have appeared since he wrote this review. (The eighth season, which ended in February 2012, is reported to be the last.) Only the first four seasons have been released on DVD in the US.

Tue 1 May 2012

THE SERIES CHARACTERS FROM

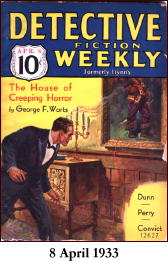

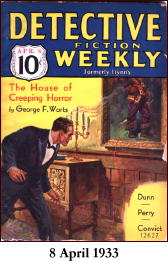

DETECTIVE FICTION WEEKLY

by Monte Herridge

#12. INDIAN JOHN SEATTLE, by Charles Alexander.

This next installment of my columns for Mystery*File features a look at another series character who appeared in the pages of Detective Fiction Weekly. The “Indian John Seattle” stories by Charles Alexander made up a short series of at least fifteen stories published in DFW from 1933 through 1939, plus two stories in Ace-High Detective Magazine 1936-37.

The stories are rural in setting. Stories published in DFW were a mixture of settings, both urban and rural. Many stories took place in urban environments, but there were a large number that were rural in setting. The Tug Norton series by Edward Parrish Ware was one that had stories in both urban and rural settings. Ware’s Ranger Jack Calhoun series was mostly rural, with a little in small towns. Even an urban series such as Morton & McGarvey by Donald Barr Chidsey had some stories in a rural environment.

Indian John Seattle is a sheriff of primarily rural Plainview County in Oregon, and his shabby office is in the courthouse in the town of Plainview. He gets his name from his learning all about Indian ways and outdoor skills. He spent his boyhood with the Nez Perce Indians. “He was an instinctive and Indian-trained hunter; criminals were his prey.†(Head Hunt)

The first story, “Death Song,†states that to catch a killer, “he must play Indian cunning on them.†This seems to work, as he flushes out the guilty man into running and later confessing the murder. This story also notes: “Many crimes of the forest Seattle had solved. He knew men—knew them through and through when they placed themselves against the background of canyon and forest where he had gained his wisdom.†In a later story, “Up Death Creek,†Seattle is called “A human steel-trap in the path of the evil-doer.â€

In the second story, “Head Hunt,†his deputy sheriff is introduced: “Hal Minton, … a tall and neat and taciturn man in his late twenties.†He is also described as “tight-lipped and grim of eye, advertised the dignity of the law.â€

Minton does not always approve of the way Seattle does things. Seattle, by contrast to his deputy, was “a bandy-legged figure in worn moleskins, wearing a time-honored Stetson, …†He is slightly bent from much time in the saddle, although he regularly uses an ancient Ford automobile he calls Flap-fender.

No mention is made of any family of Seattle’s, nor is it known where his home was. He kept odd hours as sheriff, and was likely to turn up making the rounds of the town of Plainview at 3 A.M. He seems to have lived for his job.

His cases were murder-involved, and Sheriff Seattle had plenty of experience. He “had a nose for trouble, a reaction, perhaps instinctive, to the lurking threat of danger. Years in the wilderness had equipped him with the wariness of the wolf, the cat-like cunning of the cougar.†(Head Hunt)

In “Head Hunt†he tracks down two murderers and finds the missing head of their victim, meanwhile avoiding a death-trap. Seattle carries an old .45 Frontier Model Colt, and certainly knows how to use it.

In the story, “The Weeping Lorena,†there is also no mystery as to who are the murderers and what they did. The story is regarding Indian John Seattle’s discovery of the crime and dealing with the criminals. The criminals in this story are contemptuous of the local law enforcement, calling them “hick cops.â€

However, they find that Sheriff Indian John Seattle is no fool as he quickly uncovers their scheme and crime. This story reveals that Seattle has no confidence in the abilities of his deputy, Minton. Seattle mentions that Minton is usually the first on the scene of the crime, but the last to solve the crime. In “Death Watch,†Minton actually interferes with Seattle’s attempt to uncover the crime and fasten the guilt where it belongs.

There were other series in DFW about rural sheriffs who solved crimes. One of these was the series about Sheriff Whitcher Bemis, written by Harold de Polo and published in DFW from 1927-1928. De Polo also had another rural sheriff series in DFW: Sheriff Ollie Bascomb from 1931-1941. Both of de Polo’s series have a bit of humor in them, and the Whitcher Bemis series attempts a rural dialect for the characters.

The Sheriff Indian John Seattle series is different than these two series primarily in having no humor present in the stories, and presenting the sheriff as a person of dignity, and not just a hick sheriff.

“Death Watch†involves another criminal who thinks he can outsmart Sheriff Seattle, and tries to kill him when his plans are failing. However, the criminal overlooks a simple thing in his plan, and it comes back to point the finger at him. In this story, Seattle actually kills one of the criminals. Usually he prefers to catch them alive for trial, although a number of times he has to wound the criminal in order to get his man. One of the better stories in the series.

In “Up Death Creek†Seattle has to solve a bit of a puzzle in order to finish this case. The blurb for the story reads as follows: “The bullet pneumonia of Whisky Brown, the torn boot with the missing calk—Indian John had to read those sinister signs to save an innocent man from the gallows.â€

In “Claws of the Killer†the two murderers think they have a good plan by killing someone and claiming a wild bear did the crime. However, Sheriff Seattle manages to capture both and point out a large flaw in their scheme.

“Death is a Hummingbird†involves a bizarre and very improbable method of murder that I have not seen before. Using hummingbirds to start fires! An absurd idea. The story basically falls apart, and Sheriff Seattle uses a ridiculous bluff on the murderer to make him confess.

In “Rat Nest,†a much better story, Seattle is investigating some poachers, and when he arrests one of them for murder he winds up making the biggest mistake of his career. However, when he investigates further, he learns the truth behind the matter.

In “Deputy Sheriff Rattlesnake†the murderers kidnapped Seattle and placed him in a death trap, from which he escaped. However, while he was missing, deputy sheriff Minton and the coroner argued over who should be sheriff if Seattle did not show up. So it sounds like he was feared, but not missed.

This was an average series of stories compared to the many other series that ran in DFW, but it is better than the two rural sheriff series written by Harold de Polo. I prefer the series without much humor in it, compared to the humor present in the de Polo series.

The Indian John Seattle series, by Charles Alexander:

In Detective Fiction Weekly:

Death Song April 8, 1933

Head Hunt August 12, 1933

The Weeping Lorena October 7, 1933

Bullet-Hole Business January 27, 1934

The Hicks Have It March 17, 1934

Death Watch June 16, 1934

Up Death Creek June 30, 1934

Back-Fire Murder July 28, 1934

The Lady Says October 6, 1934

Claws of the Killer March 23, 1935

Homicide Expert November 23, 1935

Death Walks on Water June 4, 1938

Death is a Hummingbird June 18, 1938

Rat Nest September 24, 1938

Deputy Sheriff Rattlesnake February 4, 1939

In Ace-High Detective Magazine:

Black Creek Brimstone September, 1936

Drummer of Doom February-March, 1937

Previously in this series:

1. SHAMUS MAGUIRE, by Stanley Day.

2. HAPPY McGONIGLE, by Paul Allenby.

3. ARTY BEELE, by Ruth & Alexander Wilson.

4. COLIN HAIG, by H. Bedford-Jones.

5. SECRET AGENT GEORGE DEVRITE, by Tom Curry.

6. BATTLE McKIM, by Edward Parrish Ware.

7. TUG NORTON by Edward Parrish Ware.

8. CANDID JONES by Richard Sale.

9. THE PATENT LEATHER KID, by Erle Stanley Gardner.

10. OSCAR VAN DUYVEN & PIERRE LEMASSE, by Robert Brennan.

11. INSPECTOR FRAYNE, by by Harold de Polo.

Tue 1 May 2012

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Marcia Muller

ERIC AMBLER – A Coffin for Dimitrios. Alfred A. Knopf, US, hardcover, 1939. First published in the UK as The Mask of Dimitrios: Hodder & Stoughton, hardcover, 1939. Reprinted many times, in both hardcover and paperback.

Eric Ambler has long been known as a master of international intrigue. His novels typically involve a more or less ordinary protagonist who has blundered into some sinister situation and has become enmeshed in it against his will. He must then extricate himself by appearing to take part in the intrigue, often as a reluctant agent for the authorities.

Ambler’s narrative style is straightforward and economical; his plots, whether simple or complex, are suspenseful; his action scenes are high points in the books.

A Coffin for Dimitrios is the story of a man with an obsession. Charles Latimer, a writer of detective novels, is on holiday in Istanbul when he meets Turkish Secret Police colonel Haki; Haki admires Latimer’s work and, like many policemen, has an idea for a novel, which he thinks Latimer should write.

The idea is old-hat, but the story Haki tells Latimer as an aside — about the criminal Dimitrios Makropoulis — fascinates the writer. Dimitrios, who has been fished out of the Bosphorus, dead of a knife wound, has been involved in murder, an assassination plot, pimping, and drug trafficking; now he lies in the morgue, and Latimer impulsively asks to view the body.

The viewing affects Latimer powerfully, and he becomes determined to trace the life of Dimitrios. His search takes him to Smyrna, Athens, Sofia, Geneva, and Paris. It reveals more facets of Dimitrios’s life than the police dossiers hold, and it throws Latimer into the company of a mysterious man named Peters who seems very interested in the fact that the writer saw Dimitrios’s body in the morgue. So interested, in fact, that he aids the investigation, and Latimer finds himself in a situation stranger and more dangerous than any in his own detective stories.

This is an intriguing and suspenseful novel with an ironic twist at the end that causes us to reflect on how little we really learn from life’s experiences. More or less faithful to it is the moody 1944 film version starring Zachary Scott, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre, which appeared under the original British title of the novel, The Mask of Dimitrios. The film’s screenplay was authored by another mystery writer, Frank Gruber.

Charles Latimer reappears in one other novel, The Intercom Conspiracy (1969).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

« Previous Page