September 2014

Monthly Archive

Wed 17 Sep 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[11] Comments

IT’S ABOUT CRIME

by Marv Lachman

SUE GRAFTON – “B” Is for Burglar. Holt Rinehart and Winston, hardcover, 1985. Bantam, paperback, 1986. Reprinted many times since.

Sue Grafton has been praised, with justification, for carrying on the traditions of the private eye novel, and I’m glad that her second book, “B” Is for Burglar, is now available in paperback from Bantam at $3.50.

Grafton breaks no new ground, but her books and her heroine, Kinsey Millhone, are so reminiscent of Ross Macdonald and Lew Archer at their best that I strongly recommend this book, The setting is California’s Santa Teresa, a thinly disguised Santa Barbara, the city in which Kenneth Millar lived, and one to which he frequently brought Archer.

Millhone, like Archer, is a decent person, and she clocks as many miles on guilt trips as he did. Both of their creators provide excellent prose, even if they did go overboard on similes. Grafton has a wonderful career in front of her, and a little more discipline as to that tendency should permit her to consolidate her considerable talent and provide us with some of the best hardboiled mysteries of the next few decades.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 8, No. 5, Sept-Oct 1986.

Editorial Comment: It is now 28 years since Marv wrote this review, and Sue Grafton’s latest is “W” Is for Wasted, published last month in paperback. Question: What is “X” for?

Wed 17 Sep 2014

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

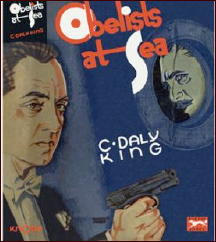

C. DALY KING – Obelists at Sea. Knopf, US, hardcover, 1933. Heritage, UK, hardcover, 1932; Penguin Books, UK, paperback, 1938.

During the bidding for a number in the ship’s pool on distance traveled by day, the lights go out and Victor Smith, either a copper king or a Western railroad magnate, is shot twice in the heart. Only one gun is found to have been fired, and that is proved not to have committed the murder. Smith’s daughter also dies, although of what cause is not known. To add to the complexity, Smith had taken or been given poison almost immediately before he was shot.

The case is too much for the ship’s detectives, so four gentleman aboard assist in the investigation. Dr. Hayvier, a well-known behaviorist, Dr. Pechs, an equally well-known psychoanalyst, and Dr. Pons, inventor of Integrative Psychology, and Professor Miltie, who had carefully avoided being identified with any of the schools of his “science” — all have their theories, all different, with different suspects.

Put aside the fact that the Meganaut has ten decks above the water line and a crew of at least a thousand and that Captain Mansfield invariably refers to it as a “boat.” This is still a fascinating, albeit a bit slow, novel.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 11, No. 3, Summer 1989.

Editorial Comments: While I do not know if all four of the detective characters in this novel appear in all of the books below, Professor Pons is stated in Hubin to be in each of them.

The Dr. L. Rees Pons series —

Obelists at Sea. Knopf, 1933.

Obelists en Route. Collins, UK, 1934.

Obelists Fly High . H. Smith 1935.

Careless Corpse. Collins, UK, 1937.

Arrogant Alibi. Appleton, 1939.

Also of interest, I believe, is the following quote taken from author Martin Edwards in his review on his blog of C Daly King’s mystery output in general:

“‘Obelist’ was a word that King made up. He defined it in Obelists at Sea as ‘a person of little or no value’ and then re-defined it in Obelists en Route as ‘one who harbours suspicion’. Why on earth you would invent a word, use it in your book titles, and then change your mind about what it means?”

For more on C. Daly King, the mystery writer, may I also direct you to Mike Grost’s comments about his work on his website.

Tue 16 Sep 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

RIDE CLEAR OF DIABLO. Universal International, 1954. Audie Murphy, Susan Cabot, Dan Duryea, Abbe Lane, Russell Johnson, Paul Birch, William Pullen, Jack Elam, Denver Pyle. Director: Jesse Hibbs.

While Ride Clear of Diablo may not be the best Western ever made, it’s nevertheless an entertaining one. Directed by Jesse Hibbs, the film stars soldier-turned-actor Audie Murphy as Clay O’Mara, a man who seeks revenge for the murder of both his father and brother at the hands of cow rustlers.

O’Mara’s good with a gun, but he’s still got a lot to learn about how the world really works. It’s this juxtaposition of fluidity with guns and naivety about society that makes Murphy’s O’Mara an interesting character. True, O’Mara’s not the sort of brooding hero that Randolph Scott portrayed so successfully in the Ranown cycle, but he’s a step above the typical gunslinger hero that populated hundreds of 1950s Westerns.

And there’s more to the film than Murphy. Although the former World War II hero got top billing, the real star of the show is Dan Duryea, an actor so incredibly good in portraying bad guys. In Diablo, Duryea portrays Whitey Kincade, a wild-eyed outlaw with a hyena laugh who takes a liking to the green Clay O’Mara.

After a series of twists and turns, Kincade eventually teams up with O’Mara and assists him in capturing and killing the men who were both directly, and indirectly, responsible for the deaths of his brother and father.

O’Mara has another interest besides revenge. Her name is Laurie Canyon (Susan Cabot). She happens to be the niece of the sheriff, Fred Kenyon (a well cast Paul Birch), who hires O’Mara and instructs him, for dubious reasons, to bring Kincade in for justice. She also just happens to be engaged to local attorney, Tom Meredith (William Pullen), who is actually the man responsible for murdering O’Mara’s brother and father. The plot thickens.

Along for the wild ride in and out of Diablo is future Gilligan’s Island star, Russell Johnson, who portrays Jed Ringer, a criminal and a double-crosser who (deservedly) gets it in the chest from Murphy’s character in a dank silver mine. Abbe Lane portrays Kate, a saloon girl and Ringer’s lady friend, who, unlike the men she associates with, turns out to have a conscience.

While there’s not all that much in the way of exceptional cinematography, the action sequences are both well filmed and choreographed, particularly those where Murphy is at the center of attention.

At the end of the day, however, it’s Duryea, not Murphy, who makes this film worth watching. If you like Duryea as a crazed villain with a wild laugh and a devil-may-care grin, you’re just going to love watching Ride Clear of Diablo. It may not be one of the fine character actor’s best-known performances, but it’s surely a memorable one.

Tue 16 Sep 2014

JOHN RACKHAM – Dark Planet. Ace Double 13805, paperback original, 1971. Published back to back with The Herod Men, by Nick Kamin. Cover art by Jack Gaughan.

I don’t read nearly as much science fiction as I used to. I don’t care for fantasy, except on occasion the humorous kind. I’m not interested in military science fiction, even though the first three Star Wars movies were a lot of fun. I don’t like long series of books in the same world or universe, especially the big fat thick ones. I know if I ever start one, either I’ll never finish or (wonder of wonders) it is what I’m looking for and it sucks all of the reading time out of my day.

I thought I’d like the new fad, or at least I think it is, of steampunk SF and fantasy — the kind that takes place in Victorian times — but I quickly discovered that a little bit of gaslights, diesel-powered zeppelins and intricately machined robots goes a long way. (If I’m mischaracterizing the genre, I assume someone will let me know, gently, of course.)

I assumed for a while that, even no one’s publishing it, what I like is good old-fashioned space opera, until I tried to read one of E. E. “Doc” Smith’s old Lensman series. No for me, not any more, not stickboard characters like this. Maybe I’m too old for science fiction, both the current variety and last century’s.

Or maybe not. Coming across a duplicate copy of one of Ace’s well-remembered and long-lost Ace Doubles, I gave it a try, and while Dark Planet showed its roots far too clearly, it was a lot of fun to read. I liked it. It’s my era of Science Fiction, circa 1966-72, when I wasn’t yet 30 but had started my teaching career and life was as fine as it could be. Maybe everyone has their own particular niche in terms of favorite reading material, and could it be that I’ve only been reading the Wrong Stuff?

Stephen Query is the protagonist in this one. He’s a misfit in the world of humanity in which he is forced to live. He doesn’t belong. He walks to the beat of a different drummer. He’s been forced out of the Space Service, where he thought he’d found a home, and sentenced to a life of drudgery and loneliness on a world with an atmosphere so noxious that it would dissolve the clothing right off your back. Sentenced there unjustly for disobeying a high-ranking officer’s direct orders. A world that’s fit only as a stopping-off and refitting station for spaceships on their way to fight in another part of the galaxy.

But loneliness he doesn’t mind, and it comes with some dismay to learn that he has been pardoned and is forcibly ordered to ship out and off to war. But the ship is sabotaged, and he and the Admiral and the Admiral’s daughter are forced to make a crash landing on the planet.

The Admiral’s daughter has one outstanding feature, according to the author, and that is her bosom. Her breasts are mentioned with obvious admiration several times, and on a planet where clothing dissolves, along with all other non-living material, we think — or at least I did — we have an inkling where this is going.

Wrong. It turns out that the world, previously unexplored, is inhabited. Not only by the people who eventually rescue the unlucky trio, but there are also sentient beings on the upper levels of the planet. Not only that, but only Query can communicate with them, being a human of other talents, and not only mentally and emphatically, but in a (shall we say) in a more sensual way, or so I gathered — since we the readers do not have the same talents, but need to be given hints at times as to what is transpiring.

Very reminiscent, I thought, of novels of the late 40s, by authors such as Henry Kuttner, in only a slightly upgraded and a bit more sophisticated telling, complete with happy ending.

But the most enjoyable aspect of this short novel (just over 100 pages, but of small print) is that I both did and didn’t know exactly where the novel was going. Not Hugo-winning material at all, in any year, don’t get me wrong about that, but this fit the bill at exactly the time I wanted to read it. Good stuff!

Mon 15 Sep 2014

DASHIELL HAMMETT – Woman in the Dark. First appeared in Liberty Magazine in three installments, April 8, April 15 and April 22, 1933. Later published in Woman in the Dark, a digest paperback original collecting six stories, including the title novella: Jonathan Press, 1951. Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1988. Vintage Books, softcover, 1989.

WOMAN IN THE DARK. RKO Radio Pictures, 1934. Also released as Woman in the Shadows. Fay Wray, Ralph Bellamy, Melvyn Douglas, Roscoe Ates, Ruth Gillette, Joe King. Based on the story by Dashiell Hammett. Director: Phil Rosen.

Actually I recently watched the movie first, then decided I didn’t remember the story all that well and not being able to locate my copy of the 1951 paperback, I bought the more recent one from Amazon for a ridiculously low price.

For only a long novelette, there’s a lot of story involved. Hammett’s prose is crisp and clear, and I found myself really enjoying reading it again, after some umpteen years. If I were to try to summarize the story in as short a space as I could, it would go something like this. I’ll fill in more later as I go along:

A guy named Brazil (John Bradley in the movie, played by Ralph Bellamy) has just been released from prison for killing a man in a fight, and he knows he has to keep his temper from now on for fear of going back. In the course of events, however, he knocks a man down who hits his head on a fireplace. When Brazil learns the man is dying, he takes it on the lam.

This summary is far from adequate, of course, since there’s no mention of the girl who comes knocking on his door in the middle of the night (Luise Fischer in the book, Louise Loring in the movie, played by Fay Wray). Turns out that she’s on the run from the member of local gentry whom she’s been staying with as a live-in “house guest,” and all the people around know what that means.

It’s the fellow’s buddy who gets socked, though, after the two of them come to retrieve the runaway Luise. Brazil objects, not because the girl is good-looking, especially, but mostly on general principles.

For a place to hide out for a while he heads for the apartment of a former cell mate (Donny Link in the book, Tommy Logan in the movie, played by Roscoe Ates) and his full-bodies blonde wife Fan (Lil in the movie, played by Ruth Gillette), where they are welcomed, but when the police are tipped off, the safe haven suddenly isn’t so safe any more.

I hope I don’t spoil things by saying that it all works out, with a slight twist and a happy ending to boot, but a good part of the real enjoyment is Hammett’s tough, terse prose in the getting there, told in such a wonderfully atmospheric, precise fashion that I think the movie could have been filmed without changing a thing.

But while of course they did, and not only the names of the characters, most of the story comes through intact. There are two long opening scenes to set the stage that are not in the book, the first in which we see Bradley (Brazil) being released from prison, the second at the home of the local sheriff, whose daughter has had a long time crush on Bradley, and against her parents’ wishes, is there in his cabin when Louise comes stumbling in from the cold and the dark. (Fay Wray in a white dress stands out beautifully in the night sky.)

Ralph Bellamy seems to be a man of some wealth. I didn’t catch that that was so for Brazil in the book. Brazil seems to have been a rougher, tougher man than a Ralph Bellamy type, the latter seen most memorably lounging against the fireplace in his cabin, casually puffing away on a pipe.

There is a flashback in the movie that describes how Louise met her benefactor Robson (a suitably slimy Melvyn Douglas), softening her image somewhat. In the movie she’s a singer down on her luck; in the story it is less clear, but she sadly seems to acknowledge that when she is called a strumpet by the local folks, they may not be altogether wrong.

One scene in particular surprised me little when I saw it reproduced in the movie almost the way I pictured it in the book. It is when the lawyer that Brazil’s pal calls on for assistance repeatedly puts his hand on Luise’s knee, and she accidentally brushes it off with the tip of her cigarette.

What consistently breaks the mood of the movie, though, is the comic antics of Roscoe Ates as Bellamy’s former cell mate. Hammett could be amusing in a tough, hardboiled way. It isn’t over the top, but the movie really could have done without silly stuff like this.

Fay Wray is near perfect in her part, though, and the near pre-Code release date means we get to see camera shots of her beautifully long legs as she examines them for bruises, but there’s far more to her role than that.

Mon 15 Sep 2014

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

OUANGA. George Terwilliger Productions, 1936. Also released as Drums of the Jungle and The Love Wanga. Fredi Washington, Philip Brandon, Marie Paxton, Sheldon Leonard. Written & directed by George Terwilliger.

Most critics agree that the story behind this movie is more interesting than the film itself, but I found Ouanga possessed of a unique charm that kept me watching and even enjoying it.

The plot is a simple affair, and writer/director Terwilliger had the sense to keep it that way. Clelie (Fredi Washington) is a Haitian plantation owner of mixed race, in love with the neighboring and very white planter Adam Maynard.

The script hints that their relationship has been more than neighborly, but as the story starts, Adam is bringing his fiancée to the island and it ain’t Clelie — it’s whey-faced blonde Eve Langley, whom Clelie decides to kill with voodoo magic. And plot-wise that’s really about it, except that Clelie herself is pursued by mixed-race overseer LeStrange (Sheldon Leonard) who has his own murderous way of dealing with unrequited love.

The story has a spare, allegorical feel to it, even down to the names of the putative hero and heroine (Adam & Eve) and the garden-like setting of the action. There’s also a fine dichotomy between the frank passion of the native peoples and the pallid complacency of their white counterparts. Terwilliger seems to enjoy cutting between vigorous folk ceremonies and tepid garden parties—and the passion in the clinches of Clelie and LeStrange quite overshadows the perfunctory romance of hero and heroine.

Terwilliger, obviously influenced by William Seabrook’s 1929 book The Magic Island, went to Haiti to film authentic Voodoo ceremonies and did a lot of research for this film, but he got chased out by the local witch doctors, who killed a member of his crew.

He ended up filming in Jamaica under primitive conditions and the result is terribly crude, but I found it oddly powerful as well — if you can get past the bad script, bad acting and laughable stunt-work. The Voodoo scenes here have a primitive and suitably awed quality to them such as I have seen nowhere else, as if the filmmaker were trying to convey to us something of his own dread and wonderment.

Ouanga ended up being largely ignored by the public and shunted off by its distributors as an exploitation show, and frankly it deserved no better. But for those who can look past its incredible ineptitude, this in a unique and haunting bit of work.

As a footnote, writer/producer/director George Terwilliger is something of a mysterious figure in the movies. An authentic pioneer of the cinema, he worked with D.W.Griffith and stayed busy in the silent era, but there’s a ten-year gap between his last silent film in 1926 and the appearance of Ouanga.

Afterwards, the screenplay of this film was recycled into an all-black movie, The Devil’s Daughter (1939) but Terwilliger himself never made another film. He died in 1970.

Sun 14 Sep 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

CHARLIE CHAN IN PARIS. Fox Film Corp., 1935. Warner Oland, Mary Brian, Thomas Beck, Erik Rhodes, John Miljan, Murray Kinnell, Minor Watson, John Qualen, Keye Luke, Henry Kolker. Story: Philip MacDonald. Based on the characters created by Earl Derr Biggers. Director: Lewis Seiler.

Charlie Chan in Paris is an eminently watchable, and overall entertaining entry in the Charlie Chan series. Starring Warner Oland as the Honolulu-based sleuth, the film follows Chan in the City of Lights as he investigates fraud at the Paris-based Lamartine Bank.

Joining him in his endeavors is “Number One Son†Lee, marking Keye Luke’s debut appearance in the series. Filmed with some unique camera angles in an atmospheric setting, the movie is one of the better Chan films I’ve seen recently. It’s just a bit darker, both thematically and visually. Chan even carries a gun in this one, and he’s not afraid to point it at suspects.

Soon upon arriving in Paris, Chan encounters a mysterious disfigured-looking man who asks him for change. Chan, humble gentleman that he is, assumes the man to be a typical street beggar, and kindly obliges. But this mysterious looking man, who we are led to believe is a shell-shocked veteran from the Great War, shows up time and again, first in a nightspot where one of Chan’s female assistants is murdered and again in the Lamartine Bank. Who is this man on crutches and what has he to do with the bank fraud?

Along the way, Chan has to solve not one, but two intricately linked murders. And although his journey begins in the bright lights of Paris, he ultimately ends up in the subterranean sewers of the Continental capital. There is a great use of shadow and lighting in the latter moments, when Charlie and a Frenchman assisting him meander through the murky depths of the city before stumbling upon a master criminal’s underground hideaway.

In conclusion, Charlie Chan in Paris is a better than average mid-1930s crime film. True, there’s not all that much depth to the story and the plot does get a bit convoluted. But if you like Oland’s Chan, just sit back and take it for what it is. All told, this entry into the Charlie Chan series is certainly worth watching.

Sun 14 Sep 2014

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Marcia Muller

EVELYN ANTHONY – The Tamarind Seed. Coward McCann & Geoghegan, hardcover, 1971. Dell, paperback, 1979. First published in the UK: Hutchinson, hardcover, 1971. Film: AVCO Embassy Pictures, 1974.

Evelyn Anthony’s novels are a cross between romantic suspense, espionage, and thriller. Romance is the most important element; her main characters are drawn together by immense physical and emotional attraction, often under circumstances of danger and stress. Exotic locales, international events, and political intrigue round out her successful formula.

The Tamarind Seed (made into a film in 1974 with Julie Andrews and Omar Sharif) opens with the arrival of Judith Farrow at Seaways Airport in Barbados. Judith, a young widow who is assistant to the director of the International Secretariat at the United Nations, is getting away from it all — mostly from the memory of a shattered love affair with a high-placed and very married British diplomat.

Within days she forms a friendship with a man staying at her hotel, but this time Judith resists romantic involvement: The man is Feodor Sverdlov, a Russian diplomat, most likely a spy, and also married, to a physician who has remained in the USSR.

Upon their return to New York, Judith and Sverdlov continue to see each other, but things are not simple for them. Judith, a British subject, is visited by members of her country’s intelligence establishment, warning her to steer clear of Sverdlov. And Sverdlov returns to find his male secretary mysteriously absent; his wife’s petition for divorce follows.

When Judith delivers a frightening message from one of his colleagues, he fears for his life, and he defects to the British. But doing that means involving Judith in a desperate and dangerous scheme.

This could be standard romance fare, except for Anthony’s strong characterization and skillful use of multiple viewpoint. Her backgrounds are well researched, and her grasp of international affairs keeps an otherwise typical love story moving along at a fast pace.

Other noteworthy novels by Anthony are The Rendezvous (1983), which deals with Nazi war criminals; The Assassin (1970), concerning a Russian assassination plot during an American election; The Malaspiga Exit (1974), about international art thievery; and The Defector (1981), another novel about tom loyalties to one’s country.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Sat 13 Sep 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

JOHN LESCROART – Dead Irish. Donald Fine, hardcover, 1989; Island Books, paperback, 1991. Signet, paperback, 2005.

— The Vig. Donald Fine, hardcover, 1990; Dell, paperback, 1992. Signet, paperback, 2006.

— Hard Evidence. Donald Fine, hardcover, 1993; Ivy, paperback, 1994. Signet, paperback, 2002.

These came highly recommended by my local mystery book store for their local color (San Francisco), and superior plotting and characterization. I didn’t find the local color very effective (and this is something I do appreciate when it’s well done), but I enjoyed the first two books for their portrait of Dismas Hardy, former cop, former lawyer, present bartender who finds his interest in life reviving after the death of his child and subsequent divorce as he’s drawn into investigations that the police want to close the books on but that he stubbornly insists on pursuing.

My favorite character in the two books is not Dismas (who’s not unappealing) but his homicide detective friend, Abe Glitsky, who has his own crisis in The Vig and sets the wheels in motion for a transfer to L A.

I note that the L. A. Times also thinks the books are “replete with convincing details of contemporary life in the bay area.” From that, I can only conclude that life in the Bay Area is not so different from me in Pittsburgh, or Salem, or Alvin, or wherever else people hang out at bars, have difficult relationships, and make decisions that don’t always (or even often) turn out to be the right ones (if there is such a thing as a right decision).

Hard Evidence is a horse of a somewhat different color. Diz is working as an assistant D. A. but soon resigns and signs on as defense lawyer for his former father-in-law, a judge accused of killing a Japanese call girl.

This is, then, a courtroom drama, a genre that I avoid like the plague, but I found I couldn’t put the book down, and probably enjoyed it at least as much than the other two books in the series. Abe Glitsky plays a less prominent role and the novel is quite long, but I found skimming wasn’t working so I settled down and read the text about as closely as I read anything these days.

I still don’t get any strong sense of place, but the relatively small cast is well portrayed, the puzzle (it’s not just a trial) is intriguing and the characters are all irritating and sympathetic in roughly equal proportions. I will put this in the plus column.

Sat 13 Sep 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[15] Comments

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

ARTHUR GASK – The Vengeance of Gilbert Larose. Herbert Jenkins, UK, hardcover, 1939. No US publication. First published in The Advertiser, Adelaide, S.A. in serial form commencing Wednesday 27 September, 1939. Available online at Project Gutenberg Australia.

Some of you may recall a few years back when I uncovered the career of Australian pulp novelist Paul Savoy and his main character Blackie Savoy. Let us just say that the provenance for Arthur Gask and Gilbert Larose is much better.

Before Arthur Upfield and Bony, Australia’s best know sleuth, was Gilbert Larose, the creation of Arthur Gask, a prolific and successful writer whose career ran from the 1920‘s until 1951.

While his novels are detective stories they are much closer to Edgar Wallace than Agatha Christie with the redoubtable Larose: brilliant, testy, a master of disguise, but also vulnerable and sometimes wrong. He’s no Holmes though. He’s a happily married man, and in several books he himself is on the run from police. Like Upfield’s half=aboriginal Bony, there is more than a touch of adventure that creeps into Larose’s adventures.

Most of the Larose novels I have read open in thriller country, but end in the courtroom. In more than one of them law gets a close shave in lieu of justice and Larose has a liberal attitude towards his official duties. I suppose being a fugitive from them would do that.

The books take place in Australia or in England where Scotland Yard is always happy to have the great Larose on hand.

I’ve chosen The Vengeance of Gilbert Larose because H. G. Wells highly praised this one on its appearance in the UK. Bertrand Russell was also a fan and at age 78 made the effort to meet the 81 year old Gask.

Gask was London born and moved with his bride in 1920 to Adelaide where he practiced dentistry. In 1921 he paid to have his first book published, The Secret of the Sandhills, and it was an immediate success. Into his eighties he was producing two 80.000 word novels a year and died writing one.

That much is covered in Wikipedia.

Gilbert Larose first appeared in 1926 in Cloud the Smiter (great title) and last in 1952 in Crime Upon Crime. Neither he nor Gask changed a lot over that time, but why argue with a winning formula.

In Vengeance of Gilbert Larose our hero’s task is nothing less than preventing a dictator from undermining British morale on the eve of War. Of course the real thing caught up with Gask and Larose before the book began serialization, but that means little. Larose who, as the newspaper says ‘tempers justice with expediency,’ is up to the task.

We open with a certain dictator living high on a mountain eyrie discussing events with a certain Von Ravenham, principally the problem of Lord Michael and Sir Howard Wake, influential men who have gone on to call the country an ‘insane asylum’ in print. Something must be done about this.

“No, go to that man in Great Tower street we are having dealings with. Pay him well — give him £10,000 — and there should be no difficulty. Give him part of the money down. He seems reliable and has always delivered the goods up to now.”

The deadline is before Lord Michael can sail for America and muddle the mind of the Americans as well. Add to this the Dictator himself has been studying English and plans to shave his mustache and go to England himself to supervise.

All Geoffrey Household tried to do in Rogue Male was kill him.

And we’re off.

Now there would seem to be no possible connection between the great autocrat of that lonely building upon the mountainside and an insignificant looking little convict in a prison in far off England. Yet, at that very moment Fate, like a malignant spider, was starting to weave a web whose threads were destined ultimately to entangle them both. (Prose like this is enough to make you reconsider Wells and Russell both.)

The insignificant little convict is named Bracegirdle, and he has just done six years for poaching. He’s a good enough sort and the Governor of the prison asks Gilbert Larose to give him a hand if he can. Meanwhile in Essex, Pellew and Royne are running a wine distribution business but it isn’t their first concern. As Von Ravenham shows up on their doorstep they are in a minor pickle and forced to hire a local mechanic, someone they can keep quiet and control — like a former convict. It gets worse when Von Ravenham reveals he knows they are using the business as a front for a criminal enterprise.

But he will keep quiet if they are willing to ‘shoot, stab, and strangle’ two men for him.

I love it when a plan comes together.

Now, literally, Chapter 2.

Things get more complicated for Pellew and Royne as they wait for a shipment of cocaine to arrive from a tramp steamer. They rescue a swimmer from the sea, and fear drawing to much attention if they drown him.

Meanwhile as they whisper desperately, the half-drowned man’s keen ears pick up details. His papers say he is Kenneth Bracegirdle, a ticket of leave (ex-convict) man who just happens to be what they need, a mechanic.

You’re getting ahead of me. Ex-convicts don’t have keen ears do they? But Gilbert Larose does.

Larose overhears them proposing murder, but who? In the meantime he gets the job and waits.

I can’t help wondering here if Upfield read Gask, because this is the kind of thing Bony was always doing, though in much better written stories.

Larose plays at a dangerous game, half blackmailing them to keep from being silenced while trying to get the goods on them. How long can he keep these balls in the air?

Pellew and Royne are busy types, they are also selling secret plans to the ‘Japs.’

Oh what tangled … Oh, skip it.

Eventually Pellew and Royne are arrested, and Larose ends up posing as Pellew’s brother Nicholas Bent for Von Ravenham, a replacement in that little business of shooting, stabbing, and strangling …

Before it is over Larose narrowly escapes torture, aids a young lady, evades a ticking bomb, and as Gask sums it up.

“But what a mighty part chance plays in this muddled world of ours and upon what small happenings do great events depend! But for the color of that girl’s eyes, her pretty mouth and the contours of her face—how different might have been the fate of that most baleful character in history! He might have passed away to the roaring of the guns and in that hell of carnage he had so long prepared for others, or he might, even now, be still in flight or exile. Instead, he lies in that shameful grave upon the lonely marshland, with that other murderer to keep him company until the resurrection morn.”

Household’s hero just went back to hunt him.

Okay, it’s rah rah, pre-war spirit lifting, and it is hardly deathless prose. Admittedly it is much closer to my Paul Savoy than I ever expected to find — but it is fun, harmless, and a few of the mysteries aren’t bad. Gask can write when he chooses to, and the person you think is Larose

isn’t always who you thought.

Granted coincidence and dumb luck play too great a role in the game, and it is hard to see Larose as a great detective as his detective work tends to be the being in the right place at the right time sort, and the few deductions he makes could only come about because Gask let him read the manuscript ahead of time. Gask and everyone else tell you he is a great detective, so he must be one, I’m just not sure on what basis.

I’ve enjoyed the ones I read, though. If it is not great writing, it is pleasant almost nostalgic bad writing. It’s the equivalent of discovering a pulp detective you never knew about. Even better these are free to download, and very few of his books are unavailable in that form.

For all that these are fast, fun reads, a step above Sexton Blake and below Edgar Wallace and George Goodchild. They aren’t dull, and Larose does grow on you in time.

As an Upfield fan I found it especially interesting, because Bony and Larose operate very much alike and Bony too has an expedient view of justice, and that at least is a sign of the great detective.

« Previous Page — Next Page »