April 2018

Monthly Archive

Tue 17 Apr 2018

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

RIFF-RAFF. RKO, 1947. Pat O’Brien, Walter Slezak, Anne Jeffreys, Percy Kilbride and Jerome Cowan. Written by Martin Rackin. Directed by Ted Tetzlaff.

I resisted watching this for weeks because I find Pat O’Brien pretty easy to resist, but when I got around to it I found myself bowled over by a film of dark beauty and considerable wit.

Riff-Raff opens with more than six minutes of no dialogue: just fluid, suspenseful camerawork as a man with a mysterious briefcase boards a cargo plane from Peru to Panama. He doesn’t finish the trip, but his briefcase does, in possession of his killer, who soon seeks the protection of Dan Hammer (Pat O’Brien of course), Panama’s resident hard-boiled fixer. The guy with the briefcase meets a predictable fate, triggering a search for its contents, and setting the story proper in pleasing if predictable motion.

Someone spent some time fleshing out O’Brien’s character, and it pays off. Hammer’s office is a seedy affair in a run-down building, guarded by a sleeping dog. He knows every chiseler and cop in town, and everyone in between, all this conveyed with sharp dialogue and a parade of evocative bit players doing their bits.

Plot-wise, it’s a standard riff on The Maltese Falcon, with Walter Slezak’s effeminate fat man and his hired gunsels looking for the missing whosis, Anne Jeffreys as a beauty who isn’t all she seems , and even Falcon‘s Jerome Cowan as a double-dealer in on the game. The wonder is that Riff-Raff is done with so much style and wit, the discerning viewer won’t give a damn – just sit back and be dazzled.

I should give a special mention to Percy Kilbride as Hammer’s side-kick, a part written & played to laid-back perfection, and one that got a few laughs out of me. There, I’ve mentioned it. And now a word about our Hero:

For most of this film, Pat O‘Brien is just fine, in a jaded, salty way, as the kind of American who gets stuck in a seedy/exotic milieu like Panama. Think of Rick in Casablanca and you’ll get the idea, but O’Brien seems a little sweatier, sloppier, and more true to life… or as true as you can get in a movie like this.

It’s only when the young and lovely Anne Jeffreys falls for him that the whole thing don’t work no more. More than twenty years her senior, fat and balding, he just couldn’t carry the romantic parts for me – much as I’d like to think that lovely young ladies are drawn to old bald guys like moths to the gaudy neon sign above a cheap barroom.

No, it just doesn’t click. But it’s the only weakness of a film I enjoyed a lot, and you should too.

Mon 16 Apr 2018

HARRY WHITTINGTON – Trouble Rides Tall. Abelard-Schuman, hardcover, 1958. Crest #357, paperback, 1960. Reprinted by Stark House Press, softcover, 2016, in a 3-in-1 edition also containing Cross the Red Creek (Avon, 1964) and Desert Stake-Out (Gold Medal, 1961).

One day in the life of a trouble marshal, whose hold on his job is suddenly starting to slip through his fingers. Through no fault of his own. He’s done exactly what he was hired to do — clean up the town of Pony Wells just enough so the honest, clean living residents can go to sleep without a lot of ruckus and noise going on outside their windows, while the cowboys and drifters can have their fun, and the saloon keepers, the grifters and prostitutes can successfully ply their trades — as long as they keep it quiet and (hopefully) behind closed doors.

That’s what he was hired to do, and now he’s though of as someone to be looked down upon by one half of the town and with side glances only from the other.

The day begins with the discovery of a dead saloon girl in a shallow grave — making this a crime novel as well as a western — and ends with Bry Shafter having made a decision about himself, or perhaps having it made for him. No one but he seems to care about the dead girl. His deputy is young and very obviously wants Bry’s job, and a committee of citizens from another town is in town to offer Bry the same job he has in Pony Wells, but at twice the salary.

Bry is good with both his guns and his fists, but what make this novel work as well as it does is what goes on in his mind. Shunned by snooty townsladies and a target for young gunslingers wanting to make names for themselves, Bry finds that the fine line he has been walking along has gotten finer and finer.

A character study, then, and a damned good one. I dare say that because author Harry Whittington plays his cards close to his vest, and you (the reader) never quite know how it’s gong to turn out. Is this one of he better examples of western noir I’ve read recently? I think it is.

Mon 16 Apr 2018

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Kathleen L. Maio

SARAH CAUDWELL – Thus Was Adonis Murdered. Hilary Tamar #1. Scribner’s, hardcover, 1981. Penguin, paperback, 1982. First published in the UK: Collins, hardcover, 1981.

In her first mystery novel, Sarah Caudwell provides proof that a Victorian epistolary novel, a mystery in the manner of the Golden Age, and a late-twentieth-century sex farce can all be harmoniously combined in one exceptional novel. But then, no less was expected from the child of British author Claud Cockburn and actress Jean Ross (who was Christopher Isherwood’s model for Sally Bowles).

Caudwell is a barrister, so it is not surprising that the legal profession features prominently in her story. The central character is Julia Larwood, a gifted barrister who is hopeless with the simple details of daily life. She goes on an art lover’s tour of Venice to forget the dunning of the Inland Revenue (her archenemy) and to seduce a beautiful young man or two. Her sexual success (with a taxman, of course!) is quickly followed by disaster: Soon after Julia rises from the bed of her young swain, he is found stabbed to death. Julia, not surprisingly, is arrested.

It is up to her colleagues back at Lincoln’s Inn, notably law professor Hillary Tamar, to find the real killer. Narrative and clues are provided by Tamar and supplemented by various letters, especially those of Julia to her barrister friend Selena. The tone is quasi-Victorian, very British, and highly amusing. The plot is improbable but skillfully handled. The characters are a delight. All in all, Thus Was Adonis Murdered marks a highly impressive debut.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

The Hilary Tamar series —

1. Thus Was Adonis Murdered (1981)

2. The Shortest Way To Hades (1984)

3. The Sirens Sang Of Murder (1989)

4. The Sibyl In Her Grave (2000)

Sun 15 Apr 2018

RIDERS OF THE BADLANDS. Columbia Pictures, 1941. Charles Starrett, Russell Hayden, Cliff Edwards, Ilene Brewer, Kay Hughes, Roy Barcroft. Director: Howard Bretherton.

A fairly ordinary early 40s western, except for a few observations I thought I’d make, but in truth, the only reason I watched this one is that Charles Starrett is in it, and he’s one of my favorite western actors of the B-movie variety. I also thought The Durango Kid was in it, but alas, I was wrong about that.

Among points of interest, though: Starrett plays both the good guy — a Texas Ranger — and the bad guy, two fellows who just happen to look exactly alike. So close are they that when Starrett the bad guy is wanted for murder the fellow who’s put in jail is Starrett the good guy. It takes some good camera work to get them to appear on the screen at the same time, and in fact, it was better than good.

One surprising aspect of the story is that the story begins with Russell Hayden’s brand new wife being killed, just as they start out in a stagecoach on their honeymoon. I sort of knew that’s where the story was going to go, but it was still shocking when it really happened.

Also interesting was the fact that the bad guy had a young teen-aged daughter (Ilene Brewer) who is crazy about him. You know he will be caught and hauled off to jail, and when he is, you have to wonder what will happen to her. I don’t suppose you will mind if I tell you that the movie ends with her going off to boarding school waving out of a stagecoach window.

One last point. Every so often the story stops while Cliff Edwards is given an opportunity to play the ukulele and sing. It’s OK the first time, but by the third time around, the thrill has begun to fade.

Otherwise, as I said up top, a fairly ordinary 1940s western of the B-movie variety. There wasn’t room in the story for Durango to appear, but now that I think about it, wouldn’t that have been something?

Sat 14 Apr 2018

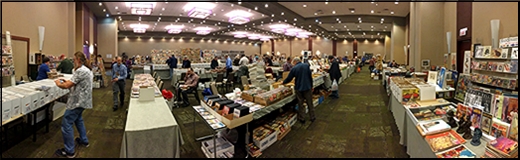

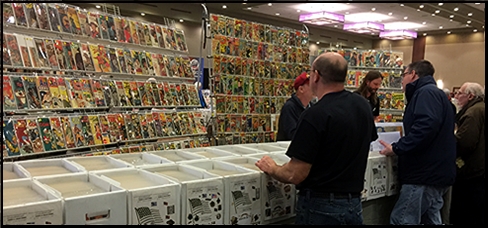

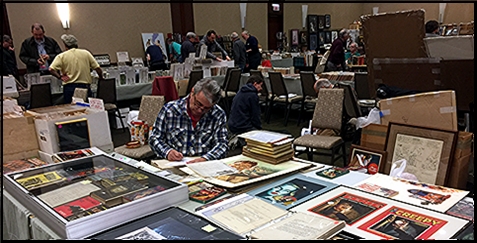

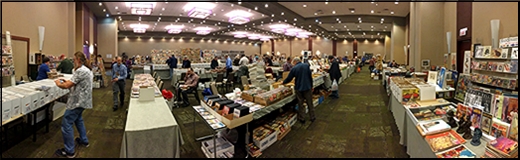

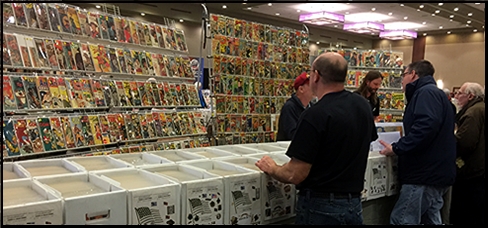

WINDY CITY PULP CONVENTION 2018 REPORT

by Walker Martin

The older I get, the longer this drive gets! Five of us drove from New Jersey to Chicago in the usual 15 seat white rental van. We take out the last two rows of seats to make the cargo area bigger. We need the space for all the books, pulps, and artwork that we will buy during the convention. During the long drive I pondered the age old question of which is worse: to forget your want list or to forget your medication. I know of two collectors who had to deal with these mistakes. I think forgetting your want list is worse. How can you collect without your lists?

First stop was the Thursday pulp brunch at the house of Doug Ellis and Deb Fulton, otherwise known as the Windy City Pulp Art Museum. Doug had recently added an addition to the large house because he needed more wall space for the hundreds of cover paintings and illustrations. After three hours of eating, drinking, and gawking at the art, we drove to the Westin Hotel, home of the convention for the last several years.

This year dealers were allowed to set up Thursday evening and I believe everyone was happy with this arrangement. Friday morning the convention officially began and there were approximately 150 dealer tables and somewhere around 400 to 500 attendees. This made for a busy three days of hunting for pulps, paperbacks, books, digests, slicks, DVDs, and artwork.

But if you were not into collecting or short of money, then there were other things to do, such as the enormous art show showing scores of pulp and paperback paintings and the film festival which ran mainly during the day on Friday and Saturday. The evenings consisted mainly of John Locke discussing “The Secret Origins of Weird Tales” and GOH F. Paul Wilson being interviewed.

Then of course there was the auction, which is one of the main attractions of the convention. It was held on Friday and Saturday evening and lasted about 4 hours each night. Friday night consisted of over 250 lots from the estate of Glenn Lord, who was the literary executor for the Robert Howard estate for many decades. Robert Howard collectors had the opportunity to bid on many magazines that contained Howard stories, such as WEIRD TALES, FIGHT STORIES, SPICY ADVENTURE, SPORT STORY, ACTION STORIES, GOLDEN FLEECE, ORIENTAL STORIES, MAGIC CARPET, STRANGE TALES, and ARGOSY.

Many of these pulps went for hundreds of dollars and two of the highest amounts were for the rare fanzine, THE PHANTAGRAPH. $1400 and $1000 for two issues that I noted, but a friend bought down some beer from his room and I had several bottles which resulted it me not noting the prices for the rest of the issues.

Saturday night I avoided the beer for awhile and noted some good prices for pulps from the Ron Killian estate. This auction also had material consigned by the attendees at the show. It’s good to see pulps come up for auction but sad to realize that they are from the estates of collectors that you will never see again. At the break I went up to hospitality room for a beer and somehow never did make it back down to the last of the auction. Is it possible that I’ve reached the stage in my collecting life that I would rather have a cold beer? Could be! I’ve been at this game for a long time now.

I bought my usual amount of books but I don’t need many pulps according to my want lists. However I did manage to find some excellent and bizarre art. I bought as Emsh interior from IF in the fifties, a very large drawing by one of the decadent artists, Beresford Egan, and a stunning Lee Brown Coye interior from FANTASTIC, February 1963. It illustrates the Mythos story “The Titan in the Crypt”. Some of my friends don’t like Lee Brown Coye but I find his art to be perfect for bizarre horror stories. There are presently three books published about his art recently and this indicates that people are realizing his greatness.

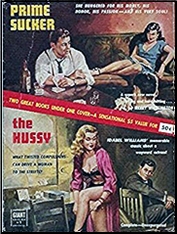

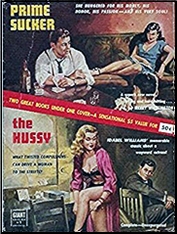

Another paperback cover I bought was one of the strange paintings that show two novels. In the early fifties there were a few fat paperbacks that had two novels and the cover shows two paintings, one upper and one lower. I remember buying PRIME SUCKER and THE HUSSY. Looks like the work of Walter Popp. I always wanted one of these strange paintings. Finally after decades of hunting!

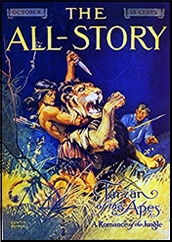

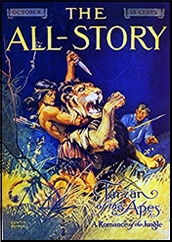

But the biggest sale of the show was a copy of ALL STORY for October 1912. That’s right the Tarzan issue! The Holy Grail of pulps! It went for $30,000 and sold right away soon after the doors opened. I’ve never seen a complete copy at a pulp convention. I once was high bidder on a copy at an early Pulpcon but it lacked the covers and the Tarzan novel was excerpted. That’s right, some crazy Breaker had cut out the Tarzan novel reducing a $30,000 to $50,000 magazine to a $400 curiosity piece.

Another high priced item was a sexy cover painting from PRIVATE DETECTIVE by Parkhurst. It was priced at $18,000 but I believe sold for $16,000. One piece of art that did not sell was a Kelly Freas cover painting from ASTOUNDING, February 1955, showing a tough guy dressed as a woman. Price was $30,000 and I guess the owner did not want to sell it but just to exhibit it.

Each year, I swear that I’m not going to buy any more art because I’ve run out of wall space. I have paintings stacked up against bookcases, etc. But being a collector is a hard job and someone has to do it…

The program book, titled WINDY CITY PULP STORIES #18 is the usual excellent book edited by Tom Roberts. 136 pages mainly dealing with the air war pulps and Harold Hersey. I noticed three books making debuts at the show:

1–ART OF THE PULPS. This is a must buy and the title says it all. Several essays by well known collectors discuss all the genres including those often forgotten such as the love and sport pulps.

2–HALO FOR HIRE by Howard Browne. This is the complete Paul Pine mysteries and published by Haffner Press.

3–BLACK MASK, Spring 2018 is the fourth issue of the revived BLACK MASK. Published by Altus Press.

Over the years, after writing one of these convention reports, I’ll hear from fellow collectors who regret not attending the show. Windy City may be over for another year but coming up is the next big pulp convention on July 26 through July 29. It’s in Pittsburgh and the details are at pulpfest.com. I highly recommend this show, and I ought to know what I’m talking about since I’ve been to almost all of them since 1972 when the first Pulpcon was held in St Louis. Almost all my pals who attended are gone now except for a handful such as Caz, Randy Cox, maybe Jack Irwin attended also, I forget. But of the hundred or so who eagerly went in 1972, we are getting down to the last man standing. Or the last Collector standing!

Don’t miss out on Pulpfest. It’s a must for collectors. We have to support Windy City, Pulpfest, Pulpadventurecon and the other one day shows or one day we won’t have any conventions and then we will be like the dime novel collectors.

I know one collector who says the two conventions are the same. No, they are not. Windy City is different and the emphasis is on art, films, and the auction. Pulpfest is also different with the emphasis on the dealer’s room and an evening full of panels and discussions.

The hotel is great and I recommend that you stay there. Sure you can get a cheaper rate down the road somewhere but the convention hotel is where all the action is.

I hope to see you there!

PS. Thanks to Sai Shankar once again for the use of his photos. All of the larger ones are ones he took. To see many more of the photos he took at Windy City, check out his Pulpflakes blog here.

Fri 13 Apr 2018

BERNARD MARA – A Bullet for My Lady. Gold Medal 472; paperback original; 1st printing, March 1955.

I didn’t buy my copy of this book when it first came out, although I might have and I lost or misplaced it later on. But I have had the copy I just read for probably just under 35 years. How do I know? (You ask.) Inside the front cover it has the stamp of a used bookstore I used to go to, a place called Tessman’s, and that’s where I spent all of my spare change when we first moved to Connecticut in 1969. All told, I must have stopped in there on the average of once a week. The price is stamped in, too. All of the paperbacks they had were 20 cents each. Gee, how I’d love to back there today.

But I digress. Bernard Mara was one of two pseudonyms used by the rather famous Irish-born Canadian author Brian Moore. You might recognize him as the author of such novels as The Luck of Ginger Coffey, I Am Mary Dunne, The Magician’s Wife and others. He was nominated for the Booker award three times, and none other than Graham Greene called him “my favorite living novelist.†(Taken from his 1999 obituary in the LA Times.)

Not bad for someone who started out by writing paperback originals for Harlequin-Canada, Gold Medal and Dell:

— as Brian Moore

Wreath for a Redhead. Harlequin #102, Canadian pb original, 1951.

= Reprinted as Sailor’s Leave, Pyramid #94, 1953.

The Executioners. Harlequin #117, Canadian pb original, 1951.

= No US edition; reprinted in Australia by Phantom Books (paperback).

— as Bernard Mara

French for Murder. Gold Medal #402, pb original, May 1954.

A Bullet for My Lady. Gold Medal #472, pb original, Mar 1955.

This Gun for Gloria. Gold Medal #562, pb original, Mar 1956.

= Reprinted as Wild as by Edwin West in a pirated edition (Zodiac pb, 1963).

— as Michael Bryan

Intent to Kill. Dell First Edition #88, pb original, 1956.

Murder in Majorca. Dell First Edition A145, pb original, Aug 1957.

You might find this interesting. Here is how one Internet source describes his early work:

… Following a tentative start as a short-story writer, he began trying his hand at hack thrillers in the Chandler-Hammett mode, under the name of Brian Mara, before taking off into serious fiction in 1955 with

The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne.

Other than the books above, only a few of his later books could be described as being mystery-related. Using Al Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV as a source, they are:

The Revolution Script. Holt Rinehart & Winston, 1971.

The Color of Blood. E. P. Dutton, 1987.

Lies of Silence. Doubleday & Co., 1990.

The Statement. E. P. Dutton, 1996.

Copies of A Bullet for a Lady, in about the same condition as the one I have, are offered on ABE at $30.00 and up. Not bad for a 20¢ investment, and now I really wish I could go back. (And take a look at the prices wanted for the Harlequin editions. They don’t seem to be scarce, but my oh my.)

What I do not think is precisely true is that Moore was writing in “the Chandler-Hammett†mode. I think someone was stretching matters there, using the only names the writer could think of (or thought his readers could identify with). Hammett and Chandler are always used as a crutch by (and for) people not so familiar with the field, when they cannot come up with names on their own.

I’m reminded a little of Eric Ambler myself, but with a hero a little more knowledgeable and capable than some of the innocents (more or less) in Ambler’s work, guys here and there overseas, mostly postwar Europe, who fall into trouble and struggle to get out, and trouble not of their own doing. The adventuresome kind of guy, scraping by, doing this and that, independent and on his own. Jack Higgins’ earlier heroes fall into this category, people like Jack Nelson in The Khufra Run. But since he came along later, then how about Harry Bannock in Edward S. Aarons’ Girl on the Run?

It is no coincidence, I do not believe, that the Aarons book was also published by Gold Medal, nor that later on many of Higgins’ earlier books first appeared in paperback in this country as Gold Medal’s.

The hero in Bernard Mara’s book is Josh Camp, and he is a partner in a small (two person) aviation company based in France, specializing in small jobs that take them all over the world. In 1955, when this book was written, the world was huge, and men who flew around it on their own were greatly to be admired.

When Camp’s partner goes missing in Spain, Josh does not hesitate. He immediately goes to find out what went wrong. And as soon as he lands in Barcelona, he is met by a beautiful woman who tells him that Harry is dead. This is on page 7, and this is where the story begins.

Mara [aka Brian Moore] had a way with words, even at this early stage of his career. Josh checks into the hotel where Harry stayed in Barcelona, and the elderly bellhop leads the way to up to his room. From page 22:

We went up. My room had a thirty-watt light bulb, a bathroom so small you could shave and shower at the same time, and a small balcony looking down at a street as narrow as an alley. A sign on the back of a door said it cost the equivalent of seventy-five cents a night. I gave Grandfather a bill and he left. The place was clean, but being in it made you feel dirty. I took my jacket and shirt off and began to wash. Harry must have been pretty broke to stay here. Not that we hadn’t stayed in worse places when the going was rough. But Spain is the cheapest country in Europe and Harry was on expenses. Still, if he was running from something, the Strasbourg was an ask-no-questions joint.

The language is picturesque, and for readers never more than 200 miles from home, Mara/Moore makes them feel as if they were. I must have led a sheltered life myself. Look at the lady on the cover. If I ever met a lady like that, I know that I wouldn’t be able to say a word. I wouldn’t even begin to know what to say.

In the first 50 or so pages, Josh meets: three women, all enigmatic but beautiful in varying ways; one tough guy; one second- or third-rate toreador; a dwarf; miscellaneous (but not very friendly) cops; and assorted cab drivers and hotel staff. They all have different agendas, especially the three women and the second- or third-rate toreador. All the cops care about is getting Josh out of the country, and they give him only 24 hours to do so. And therefore only 24 hours to discover how Harry’s death happened and who was responsible.

When I got to page 57, I made myself a note. It says, “Do you know what? None of this makes any sense.†On page 67, Mara/Moore rightly decides that a sort of a recap is in order, and by page 84, the true story starts to come out. What it is that the bad guys want and at the same time, to some extent, at least, an idea of who the good guys are.

As you may know, Gold Medal paperbacks in the 1950s were usually only 160 pages long. They could almost be read in a day, and this book is no exception. It may surprise you if I were to tell you that it is the first half which is the more interesting – the half in which confusion is king – but it is so. Once the story rights itself around and heads off in the right direction, it is as if the mystery is gone, as if the story from that point on is a mere formality, as though (but not quite) it’s only going through the motions.

Go figure. An “A minus†perhaps for the first half, and a “C plus†for the second. The works out to a solid “B,†doesn’t it? That’s just about what I would have called it, anyway. If I were still using letter grades.

Thu 12 Apr 2018

JOHN ESTEVEN – Graveyard Watch. First appeared in Detective Story Magazine, October 1936. First published in book form by Modern Age as a digest-sized paperback (with dust jacket), 1938.

I listed the pulp magazine edition first because that’s the one I read, only to discover that the story came out later in a rather hard to find PBO (paperback original) all the way back in 1938. In the magazine version it takes up 79 pages of two columns of small print. It reads as though it’s complete, but I don’t have a copy of the paperback, so I can’t tell for sure you whether that’s true or not.

“Graveyard Watch” is the first case given to a young Irish cop named Patrick Connelly to handle on his own. He’s asked by his superior to work undercover in a rich man’s house as a phoney PI to ostensibly guard some jewelry, but in reality to intercept a shipment of cocaine that word on the street says will be coming through the manor, which is located somewhere along Chesapeake Bay.

The house has its share of various people and household staff living there, and they all become suspects when its owner is found dead in the coffin in which his recently deceased brother was last seen occupying. Questions include: who killed him, what happened to the brother, where’s the cocaine (you will not be surprised how it was introduced into the house), and who’s after the jewels?

John Esteven was the pen name of a academic named Samuel Shellabarger, who went on to become quite famous as a writer of historical fiction, at least two of which went on to be blockbuster movies. It will come as no surprise, therefore, when I tell you the writing is quite good — better than average — for one of these potboiler detective mysteries of the 1930s, of which this is a prime example. All the ingredients are there, but in an amateurish way, in the original sense of the word.

There are lots of clues and skulking around by all of the possible suspects, but the ending, I thought, could have been written a lot more tightly. As is, while effective enough, it’s also a trifle muddled.

All in all, while it has its moments and is perhaps as good as some of the other Golden Age of Detection mysteries by obscure authors today, Graveyard Watch is probably not worth your effort (or cash in hand) to track down. For completists only.

Wed 11 Apr 2018

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Robert E. Briney

JOHN DICKSON CARR – The Third Bullet and Other Stories. Harper & Brothers, hardcover, 1954. Bantam #1447, paperback, 1956.

The virtues of Carr’s detective novels are present in his short fiction as well. He gets about his work with more directness, and there are fewer atmospheric side trips, but the ingenuity of plot, the sprightly dialogue, and the smooth misdirection are all in evidence. The seven stories in this collection are the cream of his detective short stories.

The title story is actually a long novelette, originally published in England in 1937 and later reprinted in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, where all the other stories in the book first appeared. (The book is dedicated to Frederic Dannay, EQMM‘s founder and editor,” who inspired so many of these stories.” )

“”The Third Bullet” is a fully developed locked-room story, complete with floor plan, false alibis, and a thoroughly detestable villain. In “The Clue of the Red Wig,” CID inspector Adam Bell and a delightful interfering reporter, Jacqueline Dubois, investigate the murder of health-and-exercise columnist Hazel Loring, found beaten to death, “half-dressed, in a public garden on a bitter December night.”

Three of the stories are locked-room crimes investigated by Dr. Gideon Fell: “The Wrong Problem,” “The Proverbial Murder,” and “The Locked Room.” “The Gentleman from Paris” is an EQMM prize-winning story set in Paris in 1849, in which the identity of the detective is of as much interest as the solution to the crime. The remaining story, “The House in Goblin Wood,” originally appeared under Carr’s pseudonym, Carter Dickson, and features Dickson’s series detective Sir Henry Merrivale. A girl disappears from a country cottage, all of whose exits are locked or under observation. The story is one of Carr’s most ingenious, and also one of his grimmest, in spite of the classic pratfall with which it opens.

This collection is a perfect accompaniment to “The Locked Room Lecture” [from The Three Coffins], offering cleverly wrought demonstrations of all of Dr. Fell’s analytical points. It also demonstrates the diversity that can exist within one seemingly restrictive category of detective story. And the stories are, above all, immensely readable.

Among the more than fifty books published under the Carr by-line, many are worth special attention. The Blind Barber (1934) is a notably smooth blending of grisly murder and all-out farce, as a slasher-type killer is loose on an ocean liner. Dr. Fell is not on board, but acts as an armchair detective in the later chapters. Another of Dr. Fell’s cases, The Crooked Hinge (1938), has what is probably the most audacious of Carr’s plots.

He Who Whispers (1946) and Below Suspicion (1950) expertly mix eerie atmosphere with baffing murders. The latter book features one of Carr’s most interesting secondary characters, the barrister Patrick Butler. Among the non-series books, The Burning Court (1937) is the most praiseworthy.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Note: Earlier reviews of the novels of John Dickson Carr by Bob Briney taken from 1001 Midnights are:

The Arabian Night Murder.

Castle Skull.

The Devil in Velvet.

The Three Coffins.

Tue 10 Apr 2018

HONG KONG CONFIDENTIAL. United Artists, 1958. Gene Barry, Beverly Tyler, Allison Hayes, Ed Kemmer, Michael Pate, Philip Ahn. Director: Edward L. Cahn.

The only reason I can suggest to you as to why you might want to see this poor excuse for an espionage thriller is the presence of Allison Hayes, she of the slinky pantsuit and the deliciously arched eyebrows. Unless, of course, you’re a Gene Barry fan, in which you will not want to miss him doing a song and dance routine in his alter ego role as a nightclub performer.

The plot, a threadbare one to say the least, has to do with the kidnapped son of the leader of the ruler of a small Arab nation in the Mideast where the Russians are stirring up trouble. How secret agent Casey Reed (Barry) connects up that essence of story with a cheap gang of gold smugglers in Hong Kong is something I seemed to have missed. Luckily for those of us still watching, Allison Hayes is Casey’s contact person with gang of thieves, much to dismay of Beverly Tyler, who plays Casey’s piano player and who is not so secretly in love with him.

This is one of those sadly inadequate movies in which a narrator is needed to pitch in and help cover up the gaps between scenes, doing his best to explain what Casey is thinking every step of the way as he tries to work his way into the gang’s good graces.

While I can’t otherwise recommend this movie, I did watch it all the way through, and that’s a fact. I wish I could say more, but this shorter than usual review will have to do.

Tue 10 Apr 2018

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

REVIEWED BY BARRY GARDNER:

WILLIAM HJORTSBERG – Nevermore. Grove / Atlantic, hardcover, 1994. St. Martin’s, paperback, 1996.

He of the unpronounceable name is best known for the “cult classic” (which cult?) Falling Angel, which I think is a very overrated novel. Which is not to say that he isn’t talented — he is.

The time is 1923, and the place is New York City. Harry Houdini is there, making a triumphant return to the Palace and is at the height of his career and powers. A. Conan Doyle is there, too, embarking on a six-month American tour to promote spiritualism.

So is a murderer who kills seemingly at random, but always taking a story written by Edgar Allan Poe as a template for his crime. And so is the ghost of Poe himself — or at best so thinks Doyle, to whom the apparition appears with distressing frequency. Houdini and Doyle become acquainted and then somewhat estranged, owing to their opposing views on spiritualism, but work together to try and puzzle out the murders. And then both are menaced.

Well, this was … interesting. It’s a fine novel from a historical standpoint, bringing America and particularly the Big Apple of the 20s to vivid life. Hjosrtberg does a good job with Houdini and Doyle, and with Damon Runyon (who appears frequently) as well.

The identity of the killer is given away (at least to me) well before the end of the book, and in such a glaring fashion that I can only assume it was done deliberately — but why? There really isn’t all that much detection, though there’s an interesting sub-plot that provides a red herring or two.

It’s primarily a novel of atmosphere and character, and considered on that basis a goo done. Houdini is particularly colorful and believable. Hjortsberg is an excellent wordsmith, though there was one glaringly inappropriate phrase that should have been caught by an editor. It’s a pretty good book, but not an outstanding one.

— Reprinted from Ah Sweet Mysteries #15, September 1994.

« Previous Page — Next Page »