Mon 27 Dec 2021

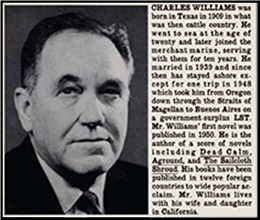

Reviewed by Tony Baer: CHARLES WILLIAMS – The Wrong Venus.

Posted by Steve under Reviews[5] Comments

CHARLES WILLIAMS – The Wrong Venus. New American Library, hardcover, 1966. Signet Signet T4158, paperback, 1970. Perennial Library, paperback, 1983. Film: Universal, 1967, as Don’t Just Stand There! (starring Mary Tyler Moore & Robert Wagner).

Boarding a commuter from Geneva to London, Lawrence Colby, freelance fixer, is libidinally drawn to the seat next to leggy Martine Randall, a smoother operator than he.

She smiled shyly. “Not really, I’m afraid. Pamela’s my roommate. I just borrowed her leg.â€

Slapstick hijinks ensue as hundreds of Colby’s smuggled self-winding Swiss watches, concealed in his multipocketed sweater, spontaneously self-wind via turbulence and start ticking like timebombs and tinkling their alarms.

She helps him out of the jam, neutralizing the watch mechanisms by dipping them in a pool of crème de menthe clogged in the airplane bathroom basin.

In exchange, he agrees to help her with a problem of her own.

The world’s best-selling romance writer has finally had sex. Now she can’t write romance novels anymore. She thinks they’re silly.

Meanwhile, unbeknownst to Miss Romance, her agent has embezzled her money and was counting on the big advance on the next novel to cover it up. So now he needs a ghost writer to write it.

He’s hired a retired 30’s hardboiled pulpster, who’s completed the manuscript. But the sex writing is too terse for the romance spinster set. So a second ghostwriter has come in to fix it. A blonde bombshell PR pro who has disappears right before she finishes the edits.

Bringing back the bombshell ain’t easy, as she’s kidnapped, chased by the mob, and is constitutionally anarchic, nonchalant, and impossible to control.

“Colby, doll, you’re on this ledge, on this bank and shoal of time. You reach your hand around a corner, and there’s a little bird that puts a new day in it. You use it up, throw the rind back over your shoulder, and stick your hand around again. He puts another day in it, or he craps in it and you’re on your way to the showers. Who worries?â€

The novel approaches postmodern territory when Charles Williams lay bare the writing process whereby the hardboiled manuscript is massaged into Harlequin romance before the reader’s very eyes.

Very entertaining caper novel. Has anyone seen the movie?