Mon 20 Dec 2021

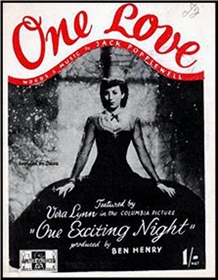

A Movie Review by David Friend: ONE EXCITING NIGHT (1944).

Posted by Steve under Films: Comedy/Musicals[3] Comments

ONE EXCITING NIGHT. Columbia Pictures, UK, 1944; US, 1945. Also released as You Can’t Do Without Love (with slightly altered credits, according to IMDb. Vera Lynn, Donald Stewart, Mary Clare, Frederick Leister, Phyllis Stanley. Director: Walter Forde.

Young singer Vera Baker (Vera Lynn) comes to London to entertain a group of RAF personnel on leave. At Waterloo Station, a pick-pocket (Cyril Smith), on the verge of getting caught, sneaks a stolen wallet into her bag. The wallet contains a cloakroom ticket to a mysterious package belonging to Michael Thorne (Donald Stewart), a former theatrical producer, which the nefarious Mr Hampton (Frederick Leister) hopes to claim as his own.

Vera, meanwhile, has been sacked after an impromptu performance at the United Nations Welfare Service. Discovering the wallet, she tries to return it – and impress its owner with her singing abilities – yet both get set upon by Hampton’s men.

The package, she learns, is a Rembrandt painting which has been sent to Thorne for safe keeping. Hampton then hires Vera to perform at a cabaret. On the night of the show, he captures Thorne and tries to kill him with the help of a doppelgänger. Vera’s efforts to rescue the imperilled producer leave her standing on a window ledge and in danger of dying herself…

An amiable romp with six musical numbers (most of which are performed with a band in view), One Exciting Night is a comedy-adventure without enough laughs or thrills to justify its place in either genre. The last of three wartime vehicles for popular British singer Vera Lynn, known as ‘the Nation’s Sweetheart’ for the achingly poignant ‘We’ll Meet Again’ and patriotic ‘The White Cliffs of Dover’, it’s light on action and focuses mainly on farce.

The plot is mildly engaging but much too convoluted, a sub-Wodehousian blend of light romance and criminal machinations which too often takes a back-seat to the songs. Lynn, here a wholesome, toothily attractive twenty-something, is charming and personable in a role which, perhaps unfortunately, requires her to be oblivious of the surrounding danger for much of the film.

A far better version could have been made with her as an enterprising amateur sleuth in accord with the mystery, yet as it is she does no detective work whatsoever.

Even the last-reel jeopardy is half-hearted, lacking any concerted effort to excite or surprise, while the late introduction of one of those miraculous face-masks, so often seen in the Mission Impossible films, makes things all the more outrageous. The film ends, too, on a slightly anticlimactic note as the villains aren’t arrested and – most distastefully – the male lead seems to settle on Vera because his true love is already married.

Nonetheless, if one doesn’t ask too much of it, One Exciting Night makes for a warm, whimsical, occasionally even fleet-footed film, with at least a couple of enjoyable songs: ‘It’s Like Old Times’ is a wistful, pop-ballad sing-along while ‘You Can’t Do Without Love’, a call for household recycling in aid of the war effort, is a fun little ditty despite playing more like a public information announcement.

Of course, it’s all somewhat unlikely, and only in the 1940s could the plot of a feature film depend on somebody returning a lost wallet. If that happened to any of us today, it really would be one exciting night.

Rating: ***