Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

ANTHONY HOROWITZ – Scorpia Rising: The Final Mission. Philomel, hardcover, 2011. Puffin, softcover, March 2012.

“Somehow you are going to persuade MI6 to send Alex Rider on a mission. You’re going to make sure the mission goes wrong and the boy gets killed … Then you’re going to blackmail them.â€

That sums up the plot of Scorpia Rising, the ninth and final book (a prequel of sorts was published earlier this year) in Anthony Horowitz’s series about fourteen year old reluctant British agent Alex Rider, who finds when his secret agent uncle dies in the first book, Stormbreaker, that he has been trained all his life a be a spy, and indeed his father was an agent as well.

Stormbreaker was a clever entertaining semi send up of the genre much in the Ian Fleming tradition of tongue definitely in cheek, what with Alex’s souped up bike and a lethal yoyo and chewing gum, but what Horowitz also took from Fleming was the knowledge that you must always play it straight, and the hero is everything. The series works because of Alex Rider, because ridiculous as the idea sounds, Horowitz makes it work. This is no Cody Banks. Alex is not only a character you cheer for, but he is one you learn to understand a bit more each book.

The books grew darker as Alex was drawn deeper into the world of spies and secret agents. All nine books take place in a single crowded year, but it becomes at least plausible as long as the novels compel you along with relentless action and one twist after another, revealing the secrets behind Alex Rider.

Alex lives with Jack Starbright, a young American woman hired as a sort of babysitter, who ends up as his guardian. Other regulars include Mr. Blunt, the cold blooded head of MI6 Special Operations; Mrs. Jones, who has a jaundiced eye to the exploitation of Alex; Smithers, the head of Covert Weapons, Q to Alex’s 007; and Sabina Pleasure (Fleming would love it), a classmate involved in his first adventure and Alex’s girlfriend.

In Scorpia Rising Alex is drawn into a trap, and faces an old enemy, Julius Grief, a clone given plastic surgery to be Alex’s twin and dark doppelganger being used by Scorpia, SPECTRE to Alex’s Bond, a ruthless terrorist organization that has been at the heart of Alex problems from the beginning.

“I will not agree to take on this child one more time. Twice was enough. I will not risk a third humiliation.â€

But of course they do. There wouldn’t be a book if they didn’t. I suppose that must be very limiting for master criminals and super villains. You can imagine Moriarty complaining that once in a while it couldn’t be Martin Hewitt or Dr. Thorndyke instead of Holmes.

Scorpia Rising is the longest of the books to that point, and a fine climax for a series that turned out to be a dark look at the excesses of intelligence, and far more accessible than any of John Le Carre’s adult novels. Horowitz (of Poirot, Foyle’s War fame, and author of numerous other young adult novels — notably here the Diamond Brothers and their best known case, The Falcon’s Malteser) is clever, inventive, playful as his model Fleming was, but unlike Fleming there is a more serious theme underlying the Alex Rider books (more serious than Fleming’s ennui anyway), and the effects of his ordeal show on what is, after all, a fourteen year old. That he keeps Alex a believable fourteen year old and not an angst-ridden mini-adult is no mean feat.

There is a stunner at the end of this one, and Alex graduates to what he has been on the way to becoming all along. At the end he escapes Scorpia and Mr. Blunt, but at a price he was not willing to pay. Despite the upbeat ending, Horowitz never suggests Alex is going to simply forget what he has seen and done, or that the can go back and be a normal teenage boy now, not entirely. Everything is nicely sewed up and closed, but you won’t buy it for a moment. Alex’s new happy life in San Francisco with Sabina’s family is presented as the finale to his adventures, but you know heroes like Alex Rider stumble on massive criminal conspiracies the way the rest of us find pennies on the ground.

You leave the series fairly certain that Alex’s days with MI6 Special Operations are only suspended until he is older.

If you like spy thrillers or James Bond, this series will be hugely entertaining. The villains are properly larger than life, the action beautifully choreographed, and the set pieces big and well drawn. Above all, without ever imitating Fleming, Horowitz manages to mine what was properly called the Fleming Effect, that ineffable voice no one has been able to echo since. Like Fleming, the writing is deceptively simple, full of short sentences and with a page-turning rhythm that easily explains why young audiences devoured these.

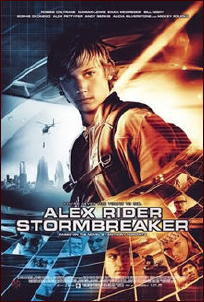

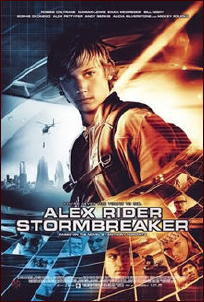

Alex Rider inspired graphic novels, audiobooks, and a somewhat disappointing movie, Stormbreaker, that was none the less perfectly cast. If you haven’t read these, find a young adult you can buy them for, and then read them yourself before giving them to him or her. Though you may have to buy a second set because you are reluctant to let them go. They really are intelligent and playful novels with a dark and serious message hidden among the lightning action.

The Alex Rider series —

1. Stormbreaker (2000)

2. Point Blanc (2001)

3. Skeleton Key (2002)

4. Eagle Strike (2003)

5. Scorpia (2004)

6. Ark Angel (2005)

7. Snakehead (2007)

8. Crocodile Tears (2009)

9. Scorpia Rising (2011)

10. Russian Roulette (2013)