Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

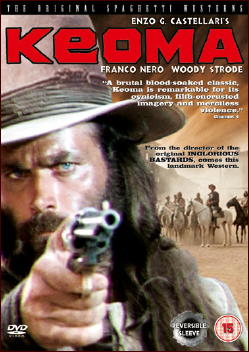

KEOMA. 1976. Also released as Django Rides Again and The Violent Breed. Franco Nero, Woody Strode, Olga Karlatos, Donald O’Brien, William Berger, Gabriella Giacobbe. Directed by Enzo G. Castallari.

An arty and allegorical Spaghetti Western with half a brain and good direction and cinematography, Keoma turns out to ultimately be more entertaining than annoying, and better acted than it has any right to be with an existentialist message at the end right out of Sartre.

Keoma: “He won’t die, he’s free. And a free man can never die.â€

Okay, if he says so, but for all that, this proves to be a really good western of its type, with first class performances by Franco Nero and Woody Strode, and one stunningly beautiful pregnant woman (Olga Karlatos) named Lisa who bears the burden of most of the allegory about life, death, birth, existence, sacrifice, suffering, freedom, and hope (well, she is very pregnant).

Admittedly that’s a lot for a western– even an Italian-made western shot in Spain — to bear, but this one manages better than most. It makes for some pretentious fun. It’s no where near as good as High Plains Drifter, but it’s nowhere near as bad as Pale Rider, as pretentious westerns go.

Nero is the gray eyed long-haired (how those braids survive holding the mess back got a bit distracting I have to grant) half-breed Keoma, who returns home after the Civil War.

“Which side were you on?â€

“It just happened I was on the winning side.â€

There he finds a spooky old Indian witch (Gabriella Giacobbe) who wanders in and out of the film like a silent Greek chorus as Keoma’s conscience and a sort of early warning signal of impending trouble. She warns him he should not have returned, but like any western hero in any western ever made anywhere, common sense isn’t his long suit, so he rides right into a group of ex-Confederate cackling coyote-mean escapees from Deliverance (are there any other kind?), taking prisoners with the plague to the mines to isolation and death.

Among them is one pregnant woman, Lisa, the stunningly beautiful Karlatos, with eyes every bit as spooky as the wolf eyed Nero. Pregnant, with straggly hair, and in extremely unflattering clothes, she is still one of the most beautiful women you will ever see in any film.

Typically he makes enemies fast, kills one of the ex-Rebs, and takes the woman to town, where no one wants her, and he promptly has to kill again and further annoy an ex-Confederate rancher and power mad criminal named Caldwell (Donald O’Brien, the film’s weakest link) who caused the plague with poisoned wells, and now holds the town hostage refusing to allow anyone to bring in medicine or help. No one ever explains just how this helps him since he has already grabbed all the land. I guess he’s just mean.

In addition Keoma finds his childhood friend and mentor George (Woody Strode) a broken old drunk waiting to die in the streets.

Keoma: “But you’re free now.â€

George: “I found out what freedom means.â€

Like heavy, man (well, it was the seventies).

Keoma it turns out was a half-breed child rescued by a fast gun, William Shannon (William Berger), with three sons of his own. Of course they are no damn good — they tortured and beat Keoma — and as ex-Confederates themselves, they ride with Caldwell and their once proud and deadly father is old, afraid to die, and fears having to kill his own sons. But he’s glad to have Keoma back.

Shannon: “We stopped slaughtering and butchering the Indians long enough to free the black man and now we are back to finish with the Indians.â€

That comes a bit out of left field, since other than the knowledge that Keoma’s village was slaughtered by white men and Keoma the only survivor, and all the bad guys, brothers included, go on about him being half-Indian, Indians have almost nothing to do with the plot except as shorthand for oppressed and exploited people, and that old Indian woman (great face) who keeps wandering in and out at key points often back lit by lightning and sunlight.

This is a beautifully shot film. Visually it is great to look at and the print I saw was off an original 35mm letterboxed master in one of those collections of twelve films, this one including One Eyed Jacks, another pretentious western, but not as good as this one despite the cast and stunning cinematography.

Keoma is about as much Tarzan or Conan here as a western hero, a sort of force of nature, the ultimate existentialist hero who worships only one thing, freedom at any price — no matter who he gets killed in winning it for them.

It’s a very physical role for Nero, mindful of the kind of action film Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas often made full of running, leaping, fighting, and defying gravity, and in the stunts that are obviously Nero, he looks and performs the physical side more than adequately. Of course he was an old hand at this and even makes a sly cameo in Quentin Tarantino’s paean to the form, Django Unleashed (for anyone who didn’t get the joke Nero — among others — this was also released as Django Rides).

You have to give the director and multiple screenwriters credit too, because this could easily have devolved into maudlin flashbacks of Keoma’s troubled childhood, but instead they chose a form of virtual Latin American Magic Realism where the characters in the here and now are physically in the flashback scenes with their younger selves. Once you get past the initial shock it is very effective and in some ways presages the famous ending of Robert Benton’s Places in the Heart.

You can guess how the plot works out: there’s the good doctor who regains his nerve; George regains his manhood; Shannon stands by his good adopted son, Keoma; Shannon and George take on the entire Caldwell army in a well shot orgy of gunfighting and violence; and Keoma ends up crucified in the rain on a wagon wheel in the middle of town only to be rescued by Lisa, the dying pregnant woman.

The final shootout in an old abandoned fort where the film opened, with Keoma battling his three adopted brothers is well staged with the screams of the woman in labor and the cries of her newborn muffling the gun fire (I warned you it was arty) and the old witch looking on.

But don’t shoot me, it isn’t my fault that Keoma, having done everything but backflips to see the child is born, then deserts him with the old Indian woman with than nonsense about a free man can’t die. See how much milk and how many diapers existentialist philosophy will buy you; carrying existentialism a shade too far as far as I’m concerned.

The major problem for me was the damn musical soundtrack, really lame senseless ballads I could barely understand that sounded like the mewling of the cattle from Red River done to music or the male part like a coyote with a sore throat trying to spit phlegm up (and that is being kind — “Do not forsake me oh my darlin'” it’s not), the woman singing alone had a vibrato on high notes that must be how Madame Castafiore sounds to Captain Haddock in Tintin. You will be amazed how many vowels she manages to squeeze into the name Keoma. She sounds like the love child of Joan Baez and Slim Whitman.

That said, the dubbing was first class with Nero and Strode at least doing their own voices.

But messy as it is at times, I more than recommend this one. It mostly succeeds at what it is obviously trying to do, there is some strong and effective imagery, plus stunts, good use of lighting and staging, and more often than not, it rises to what it seems to want to be. Granted the main villain is a bit lame, but he’s only an afterthought to the conflict between the brothers and Keoma.

And if any of you have seen it and remember, maybe you can clear up whether Keoma was just rescued by Shannon, or Shannon’s son by his Indian mother. At one point that seems to be the implication, and then later I wasn’t so sure. I guess that happens when a small army writes the screenplay. They never clear up if the people at the mine dying of plague are saved either. Guess it wasn’t worth the bother.

I enjoyed this one much more than I expected. If there is another half this good on the set then I won’t feel I wasted $5. This is one of the better thought of and appreciated later Spaghetti westerns, and it isn’t hard to see why.

Still, I can’t help but wonder if Tonto — Keoma — would have fared better here with the help of the Lone Ranger.

Just asking.