ROUND ROBIN MURDERS:

The Floating Admiral (1931) and Double Death (1939)

by Curt J. Evans

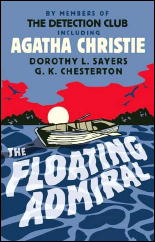

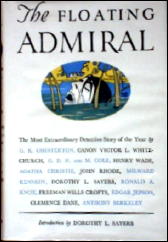

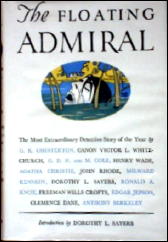

In its ongoing attempt seemingly to wring every last pound of profit out of the Agatha Christie literary estate, HarperCollins has recently reprinted The Floating Admiral, the collaborative detective novel (originally published in 1931) by fourteen members of the then recently formed Detection Club (each writing a successive chapter).

Although Agatha Christie’s contribution is a chapter of eight pages (in my 1979 Gregg Press edition) — 3% of the book — she gets top billing, with only Dorothy L. Sayers and G. K. Chesterton (the latter of whom contributed, by his own admission, a strictly ornamental prologue of five pages) also being mentioned by name, in much smaller letters. Such are the publishing perks of fame and continued books sales!

To my mind, the detective novel, requiring as it does the most scrupulous planning, is not really a form that is receptive to “round robin” treatment. Case in point: The Floating Admiral. Overloaded with complications from too many eager hands, the tale in my opinion begins to take on water and sink well before reaching its conclusion (tellingly entitled by Anthony Berkeley, “Cleaning Up the Mess”).

Nevertheless, if one is interested in authors of Golden Age detective fiction, The Floating Admiral is in many ways quite interesting, whatever its artistic failings.

Things go pretty well for the first five chapters (written by Canon Victor L. Whitechurch, G.D.H. and Margaret Cole, Henry Wade, Agatha Christie and John Rhode), with the authors refraining from over-elaboration. Unfortunately the calmly floating boat is upset by water violently churned by Milward Kennedy (his chapter, which follows Rhode’s “Inspector Rudge Begins to Form a Theory” is impertinently entitled “Inspector Rudge Thinks Better of It” — the good Inspector should not have).

Dorothy L. Sayers tries to straighten everything out that had tangled with a thirty-seven page chapter but she only makes things worse.

Ronald A. Knox’s chapter, “Thirty-Nine Articles of Doubt” (Chapter Eight) warningly raises thirty-nine problematical points that have accumulated for the authors following him to consider and Freeman Wills Crofts in Chapter Nine politely notes that, among other things, the body (allegedly of the admiral of course) was never adequately identified or an inquest arranged. But all to little avail.

Clemence Dane complains in her notes to her Chapter Eleven, the penultimate chapter, that the mystery has become “quite inexplicable to me” — and she likely has not been alone in that sentiment over the years.

Anthony Berkeley’s conclusion has been praised heartily by over-generous critics. I deem more like the curate’ egg — good in spots but essentially rotten. But to be fair to the poor fellow, he was handed the devil of a job.

The fun for me in reading The Floating Admiral is not in reading a cogently plotted detective novel (it simply isn’t one), but in seeing the narrative approach each author takes in his/her chapter:

â— G. K. Chesterton writes rich prose.

â— Canon Whitechurch introduces a charming vicar.

â— Henry Wade develops appealing and credible relationships among his policemen.

â— Out of the blue, Agatha Christie introduces a garrulous, gossipy lady innkeeper.

â— John Rhode discusses tidal movements (the admiral was floating after all) and sympathetically expands the role of the retired petty officer, Neddy Ware.

◠Milward Kennedy overcomplicates the story, as does Dorothy L. Sayers (the ingenious Sayers should have been given the opening chapter — she and Kennedy both clearly wanted it).

â— Ronald A. Knox makes a long list.

â— Freeman Wills Crofts checks alibis and has his inspector travel by train.

â— In his notes to his chapter, Knox amusingly declares, “I once laid it down that no Chinaman should appear in a detective story. I feel inclined to extend the rule so as to apply to residents in China. It appears that Admiral Penistone, Sir W. Denny, Walter Fitzgerald, Ware and Holland are all intimate with China, which seems overdoing it.”

In her recent Guardian review of the new edition of The Floating Admiral, Laura Wilson deems Agatha Christie proposed solution for the tale “as you would expect, the most ingenious” of all the solutions. Certainly it’s more tricksy than, say, the solution proffered by John Rhode (without a complicated murder means, Rhode is unable to play to his greatest strength here). It’s also absolutely absurd.

Here’s how Christie envisioned the state of affairs in the Admiral’s household (*** SPOILER *** to Christie’s proposed solution follows, obviously):

The Admiral’s niece is really his Uncle’s nephew masquerading as the niece. He has been doing this in his Uncle’s household for weeks, and is able to get away with it because he “has been an actor at one time” (that Golden Age crutch for the unlikely accomplishment of great disguises) and because the Admiral has not seen the niece since she was a child (he has seen the nephew more recently, however). The servants are fooled as well, as are the various beaux of the neighborhood, whom the nephew “takes an artistic pleasure” in vamping. (*** END SPOILER ***)

Ingenious or rather ridiculous? You decide for yourself, but I know what I think.

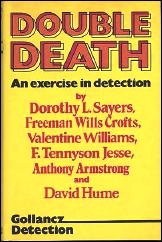

On the whole, I much preferred Double Death, a round robin novel with chapters by Dorothy L. Sayers, Freeman Wills Crofts, Valentine Williams, F. Tennyson Jesse, Anthony Armstrong and David Hume that originally appeared in the Sunday Chronicle in (I believe) 1936 and was published in book form by Victor Gollancz.

It is often stated to be a Detection Club production, but I do not see how this could be, since only two of the six writers, Sayers and Crofts, were members of the Detection Club.

In her introductory chapter to Double Death, Sayers sets up a compelling possible domestic poisoning situation, followed by a death at a railway station, at the evocatively named town of Creepe.

Freeman Wills Crofts embroiders on this opening situation ably (he even provides a stunning map of Creepe and Creepe station), as does Valentine Williams, though the latter is more known for his “Clubfoot” thrillers than his (underrated) detective novels. Unfortunately the later authors are less concerned with cluing, so that as a fair play mystery the tale ends up rather a bust (especially if you read the silly prologue, added later).

However, the writing and overall emotional situation remains compelling throughout Double Death, thus making the tale more of a success than the The Floating Admiral.

It’s interesting to note that in Double Death, written in the mid-thirties, all the authors are concerned with maintaining love interest; whereas in The Floating Admiral all the characters are sticks in whom one could not be expected take the slightest interest (well, there’s the vamping transvestite nephew, as envisioned by Christie).

As the 1930s progressed, the Golden Age detective novel began to put more emphasis on emotional situations and less on ratiocination. In the end, it is this shift in emphasis that makes Double Death more interesting than The Floating Admiral, in my view. Admiral depends for artistic success on detection and too many hands on deck sink the craft.

Yet with less than half the people involved, Double Death might have managed to work as a true fair play detective novel. Certainly Sayers, Crofts and to a lesser extent Valentine Williams made an admirable start of it.

I rather wish the novel could have been kept a collaboration simply of two: Sayers and Crofts. The two authors corresponded over the opening chapter of Double Death in the spring of 1936, with Sayers requesting and Crofts supplying pertinent points of railway station detail.

Sayers had already written her railway timetable novel The Five Red Herrings (1931) as a sort of homage to Crofts’ Sir John Magill’s Last Journey (1930) — these two brilliant books continue to stand today as the ne plus ultra of railway timetable mysteries. Double Death in their hands might well have been a classic product of the Golden Age. As it is, it is still a good read.