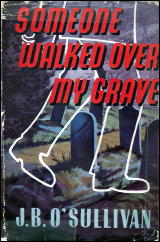

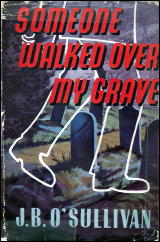

J. B. O’SULLIVAN – Someone Walked Over My Grave. T. Werner Laurie Ltd., UK, hardcover, 1954. No US edition.

As I often do, I’ll append a list of all of J. B. O’Sullivan’s Steve Silk mysteries at the end of these comments. There are a few of them, as you’ll see, but only two have even been published in the US.

Silk himself is described on the Thrilling Detective website as “a former boxer turned un-licensed PI. Quick with a wisecrack and quicker with his fists, he dresses well and chases women with vigor,” but there are no signs of fisticuffs in the book at hand, and no woman chasing either.

Silk is usually based in New York, so maybe the difference is that when he visits Ireland, as he does in Someone Walked Over My Grave, he’s on his best behavior. In fact the murder that’s solved in this book is a country manor affair, one much more suited for the likes of Supt. George Tubridy than a smooth as silk operator like Steve.

There is a point in time, however, at which the reader (this one, anyway) will suddenly realize that what is going on is a competition between the two. Who (and which approach) will solve the case first? Amusingly, though, the two end up asking the same questions of the same people and each in their own fashion, coming up with very much the same answers.

Dead is the father of a would-be bridegroom, and the number one suspect is the wayward brother (on the other side of the Irish political divide) of the would-be bride when it appears the wedding is off (therefore all of the would-be’s). Telling the story is Jimmy (no last name noted), a local reporter who spent some time in the US chronicling some of Silk’s earlier adventures.

In the grand Golden Age of Detection fashion, there are lots of suspects, some with alibis, some not, and some of the alibis are suspicious if not outright flimsy. There are several decent twists before a suspect admits to having done the crime, then an even better one before (PLOT ALERT, and maybe I shouldn’t even be telling you this) the last three paragraphs turn everything around again.

An amazing feat. I was on cruise control at the time, and it made me stop on a dime, sit up and take notice, I’ll tell you that.

The Steve Silk novels — [Adapted from the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin]

Casket of Death (n.) Grafton 1945

Death Came Late (n.) Pillar 1945

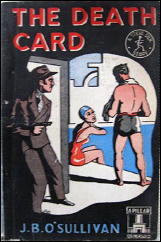

The Death Card (n.) Pillar 1945

Death on Ice (n.) Pillar 1946

Death Stalks the Stadium (n.) Pillar 1946

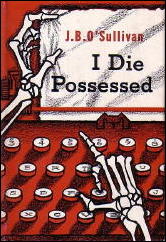

I Die Possessed (n.) Laurie 1953. US: Mill, 1953

Nerve Beat (n.) Laurie 1953

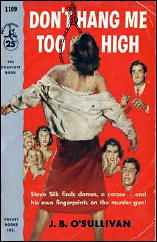

Don’t Hang Me Too High (n.) Laurie 1954. US: Mill, 1954

Someone Walked Over My Grave (n.) Laurie 1954

The Stuffed Man (n.) Laurie 1955

The Long Spoon (n.) Ward 1956

Choke Chain (n.) Ward 1958

Raid (n.) Ward 1958

Gate Fever (n.) Ward 1959

Backlash (n.) Ward 1960

Make My Coffin Big (n.) Ward 1964

Murder Proof (n.) Ward 1968

The Supt. George Tubridy novels —

Someone Walked Over My Grave (n.) Laurie 1954

Pick Up (n.) Ward 1964

Lunge Wire (n.) Ward 1965