REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

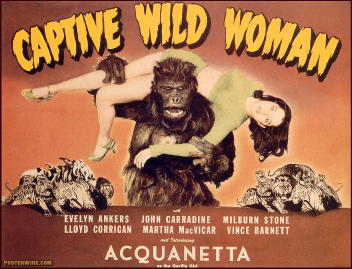

â— CAPTIVE WILD WOMAN. Universal, 1943. Acquanetta, John Carradine, Evelyn Ankers, Milburn Stone, Lloyd Corrigan. Director: Edward Dmytryk.

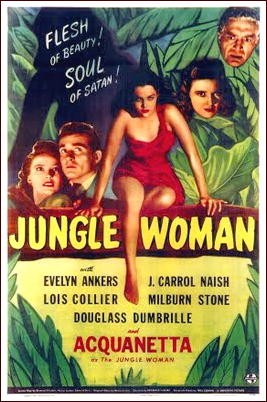

â— JUNGLE WOMAN. Universal, 1944. Acquanetta, Evelyn Ankers, J. Carrol Naish, Samuel S. Hinds, Lois Collier, Milburn Stone, Douglass Dumbrille. Director: Reginald Le Borg.

â— JUNGLE CAPTIVE. Universal, 1945. Otto Kruger, Vicky Lane, Amelita Ward, Phil Brown, Jerome Cowan, Rondo Hatton. Story & screenplay: Dwight V. Babcock. Director: Harold Young.

Among movie studios, Universal is fondly remembered for classic horror films like Frankenstein, Dracula, The Wolfman and the sequels they spawned, but the studio put out a good number of lesser efforts, and even a few second-string series, haunted by bush-league monsters who somehow never hit the big time.

One recalls (not fondly) the Spider Woman and the Creeper, both spawned by the superior Sherlock Holmes series, and both duller than dishwater. But perhaps the most persistent of the minor monsters was Paula the Ape Woman.

Captive Wild Woman (1943) initiated the series and it opens with a credit thanking Clyde Beatty for his “inimitable talent and contribution to this film.” Said contribution consists of stock footage from an old circus serial, and why they refer to Beatty as “inimitable” I don’t know, because Milburn Stone imits him all through the movie, as a lion tamer whose every foray into the cage becomes a long-shot of the back of Beatty in the earlier film.

In defense of Milburn Stone, who became a respected character actor on Gunsmoke, I have to say that he puts in a very convincing performance when called on to play Beatty’s back, and it’s only when he goes through the tame leading-man motions that interest flags.

Unfortunately, there’s rather much of this, as the plot of Captive Wild Woman meanders its way from a circus milieu to the den of a mad scientist (John Carradine) experimenting on the sister (Martha Vickers) of leading lady Evelyn Ankers, who put up with quite a lot of that in those days.

Carradine extends his research so far as to steal a gorilla from the circus and turn it into a near-human woman (Acquanetta, “the Venezuelan Volcano”) using glandular injections from Vickers, whereupon the writers decide to get silly and have Carradine take Paula the Ape Woman back to the circus, where she promptly falls in love with Stone and becomes part of his act.

But Stone is already engaged to Ankers, and when Paula gets jealous she morphs into a half-ape and must return to Carradine who is eager to extend his research even further, resulting in a four-sided triangle reminiscent of the lovers in Midsummer’s Night Dream, but without the class.

All this is handled with some amount of style by Edward Dmytryk, a director going places (like Murder, My Sweet and The Caine Mutiny) who throws in the occasional camera angle or bit of moody lighting, but to little effect; Captive struts and frets its brief 60 minutes on the screen, signifying very little indeed.

But any movie with a title like that was bound to draw customers, and returns on Captive were strong enough for Universal execs to order a sequel. Thus Jungle Woman appeared the next year.

This is a strange one, even by B-movie standards, as if, pressed for time, producer Ben Pivar decided to simply re-run the fist movie. About a third of Jungle Woman is lifted bodily from Captive Wild Woman, as stars Milburn Stone and Evelyn Ankers reprise their roles from the first film in a framing device centered around testimony at an inquest involving another mad scientist (J. Carroll Naish this time) and a dead ape-woman (Acquanetta again) found on the grounds of his sanitarium.

Said framing takes up the whole first part of the Jungle Woman, with Ankers and Stone recalling events in flashback from the earlier film, which appear in no particular order, making this thing look like a Resnais film, as the past rises to feebly haunt the present with little coherence or cohesion.

Finally, re-runs exhausted, a new cast appears, and they proceed to tell a story in flashback (did some of this anticipate film noir?) filling out the running time with an account of how Naish, visiting the circus sometime during the first film, was impressed enough to acquire the body of the ape woman, revive her, and start a movie of his own, leading to the unpleasantness that awaits those who dabble in things man wasn’t meant to etc, etc..

Well, sixty minutes pass in this manner, leading to a wrap-up that would have been fairly shocking, had anyone been paying attention. As it is, the final scene gets tossed off like the rest of the movie, and I, for one, was left wondering what they must have been thinking of when they committed this crime against Cinema.

Somehow, though, Universal thought the concept was worth another try, and the next year saw the release of Jungle Captive. This is marginally better than Jungle Woman, and if you look up the term “faint praise” in the Dictionary, you may find the words “marginally better than Jungle Woman.”

Actually, Captive benefits from the appearance of Otto Kruger as this year’s Mad Scientist, who begins by electronically reviving dead rabbits and, with the reasoning of his ilk, decides the next logical step is to steal the body of the Ape Woman from the morgue and revive that.

Kruger handles all this with commendable restraint, and somehow puts Real Feeling into lines like “I need your blood,” though things get a bit much when he decides his ape woman (played by Vicky Lane this time) needs a new brain and proceeds to check out his predecessor’s brain-transplant instructions (written on a 5×8 note card) and borrow a book titled Brain Surgery!

Maybe because it eschews the flashbacks, Captive seems to move at a faster pace, with some creepy support from Rondo Hatton as “Moloch the Brute” and effective makeup for the ape woman.

There’s also an appearance by Jerome Cowan (of whom more later) playing his usual clueless role as a detective, and Vicky Lane, though she gets no lines and has little to do, is a distinct improvement as the new Ape Woman: her strong features and large, expressive eyes remind one of the girls in drawings by Gene Bilbrew, and make me wonder what sort of career she might have made for herself with better luck than this.