Sat 19 Jun 2021

Pulp Stories I’m Reading: VINCENT STARRETT “Footsteps of Fearâ€.

Posted by Steve under Pulp Fiction , Stories I'm Reading[7] Comments

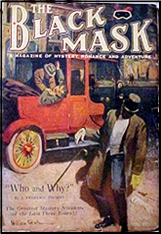

VINCENT STARRETT “Footsteps of Fear.†First published in The Black Mask, April 1920. Collected in The Quick and the Dead (Arkham House, hardcover, 1965). Reprinted in The Big Book of Rogues and Villains, edited by Otto Penzler (Black Lizard, softcover, 2017).

Dr. Loxley has it made, or so he thinks. He has killed his wife Lora, but the police are not on his trail – not as the killer, that is. He made his plans well in advance, and to all intents and purposes is considered dead as well, as he (under his own name) has completely vanished. But under a new name and a new profession, he is doing quite well: as the frosted glass door outside his outer office says, he is now William Drayham, Rare Books, Hours by Appointment.

He is friends with his neighbors on the same floor, and he does not need to leave his building. It has all the amenities he needs: restaurants, barber shops, and so on. And as a big plus, the sign on the door was “formidable enough to frighten away casual visitors.â€

This may have been an inside joke included here on the part of the author, a well known bookman of his era. Stories in this very first issue of Black Mask were far from the hardboiled fare for which it later became famous.

It is, however, reminiscent of one that magazine’s better known writers, Cornell Woolrich, with a twist in the ending that brings a severe comeuppance to the former Dr. Loxley. In spite of the new name and facial features, he becomes more and more convinced that his plans have fallen short, and a zinger of an ending worthy of a story on Alfred Hitchcock’s television show ensues, well thirty or forty years ahead of its time.

Here below is a list of the other stories in that same issue of Black Mask, taken from the online Crime Fiction Index. Only Harold Ward’s name, he being a long time pulpster, is vaguely familiar to me. I’m going out on a limb here, without reading any of the other tales, but I suspect none of the others have anything very much to offer modern day readers. This one by Starrett may be the only one that’s ever been reprinted.

The Black Mask [Vol. I No. 1, April 1920]

Who and Why? · J. Frederic Thorne

The Stolen Soul · Harold Ward

The House Across the Way · Sarah Harbine Weaver

The Peculiar Affair at the Axminster · Julian Kilman

The Puzzle of the Hand · Stewart Wells

Piracy · Harry C. Hervey, Jr.

The Mysterious Package · David E. Harriman & John I. Pearce, Jr.

A Small Blister · David Morrison

Hands Up! · Ray St. Vrain

Footsteps of Fear · Vincent Starrett

The Dead and the Quick · Gertrude Brooke Hamilton

The Long Arm of Malfero · Edgar Daniel Kramer