REVIEWED BY MICHAEL SHONK:

CAIN’S HUNDRED. NBC, 1961-1962. Vanadas Production Inc in association with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Television. Cast: Mark Richman as Nicholas “Nick†Cain. Theme by Jerrald Goldsmith (aka Jerry Goldsmith). Creator and executive producer: Paul Monash. Produced by Charles Russell.

CAIN’S HUNDRED was a weekly hour-long series on NBC. Mark Richman (later to become known as Peter Mark Richman) played Nick Cain, a former criminal lawyer who had represented the mob until he retired and decided to get married. When “The Organization†hit man missed Nick and killed his fiancee, Nick decided to join the law and go after one hundred of the top mobsters, one bad guy an episode. It is enlightening to see how different this premise was handled in the 1960s compared to today’s THE BLACKLIST. It was a simpler black and white world then.

The series aired during a time when how television was made was changing. TV continued to settle in Hollywood leaving New York (except for the networks and advertising agencies) behind. The time when advertisers produced the shows was nearly gone and more series were supported by the system we still use, what “Broadcasting†called the “magazine†system, where advertisers buy some time on various series instead of all the time on just one.

As the networks and studios took over the producing of more programs such as CAIN’S HUNDRED, they and not the advertisers were making the decisions over content and personnel. CAIN’S HUNDRED was also among the growing number of dramas to replace the half-hour format with the longer hour format.

The April 17, 1961 issue of “Broadcasting†had an article that went into great detail about the pre-production history of CAIN’S HUNDRED. According to Robert Weitman, vice president in charge of programming for MGM, CAIN’S HUNDRED was in pre-production (before filming began) for nearly a year.

“The idea of retired criminal lawyer who once represented the ‘big crime’ syndicate but now has agreed to help top level government officials stop crime before it happens was developed at MGM-TV and presented to David Levy, NBC-TV’s program vice president, and later to NBC’s president Robert Kintner. They liked it, so we got Paul Monash, who wrote the original two-part UNTOUCHABLES script, to do a first script for us and when he had a rough draft we sent it to NBC and they said go ahead and polish it. When they got the finished script, they said go ahead and shoot it. That was Dec.15. I set March 1 as a deadline and went to work.â€

A director for the pilot was hired, stages were built and casting began. January 19, 1961 the filming of the pilot began. It took eight days to film the pilot. A rough cut was ready for viewing on February 15th. On February 28, MGM executive Weitman left Los Angeles and headed to NBC in New York.

NBC liked the pilot and scheduled the crime drama series to air in the fall on Tuesday at 10pm. Producer Charles Russell was hired and with Paul Monash began to hire the staff of writers and directors. At this point filming was to begin May 7th. However, production did not begin until June 5th (according to “Broadcasting†June 12, 1961 issue).

The series usually aired opposite ABC’s ALCOA PRESENTS and CBS’s hit GARRY MOORE SHOW. Ratings were not good, and CAIN’S HUNDRED was rumored to be facing early cancellation but surprised many by surviving through the entire season.

According to “Broadcasting†(December 18, 1961), thirteen episodes of CAIN’S HUNDRED was the original order, than an additional seven episode were added, and finally another ten, making a total of thirty episodes.

Beyond being opposite of the hit series THE GARRY MOORE SHOW, the series faced an additional ratings challenge with clearances. According to “Broadcasting†(February 5, 1962) CAIN’S HUNDRED aired in its NBC time slot (Tuesday, 10pm) on 126 stations while 25 stations delayed it and aired it in another time period.

I have seen two episodes of CAIN’S HUNDRED, “Blues For the Junkman†and “The Plush Jungle.â€

“Blues For A Junkman – Arthur Troy†(February 20.1962). Written by Mel Goldberg. Directed by Robert Gist. GUEST CAST: Dorothy Dandridge, James Coburn, and Ivan Dixon. *** Nick tries to help old friend jazz singer Norma Sherman who is just out of prison for drug use. Norma finds her husband had left her for another woman. Nick and nightclub owner Arthur Troy try to help get her a license to perform in nightclubs, but problems arise. “The Organization†forces drug-hating Arthur to handle a drug shipment gone wrong. Nick is working this week with a Lieutenant in narcotics who wants Nick to use Norma to find the drug shipment.

This was a quality production for the era. The music numbers by Dandridge highlight the episode but never got in the way of the story. The characters were as complex as their problems and no easy answers were offered except for the flawed predictable ending.

The other episode I have seen, “The Plush Jungle†is available at the moment on YouTube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bCEjI_JvXzo

“The Plush Jungle – Benjamin Riker†(January 2, 1962). Written by Franklin Barton. Directed by Alvin Ganzer. GUEST CAST: Robert Culp, Larry Gates, and John Larch. *** One of the top men in “The Organization,†Benjamin Riker decides to take over a major corporation traded on the stock exchange. First, Riker uses usual organized crime strong-arm methods to intimate the company’s suppliers to drop the targeted company then he took advantage of the stock market and dropping stock prices and finally the growing conflict between the company’s President and his ambitious young son.

Production values behind and in front of the camera were better than the average TV series of the time, but the series was faced with impossible challenges to overcome. CAIN’S HUNDRED, as all television dramas at the time, was dealing with the outcry over TV violence and THE UNTOUCHABLES.

While “Blues For A Junkman†had a brief shoot-out, “The Plush Jungle†avoided showing any action or violence, instead using dialogue to imply the threat of violence. This left only the emotional conflict between father and son to supply the story’s drama and tension.

Despite the handicaps, writer Franklin Barton’s script developed the conflict well and used the hour-long format to the drama’s advantage. Director Alvin Ganzer did a fine job capturing the emotional tension without letting the all dialogue story get too dull. But I have never seen any TV series treat its lead with such lack of respect as Cain was in “The Plush Jungle.†Unlike the episode “Blues For a Junkman,†Cain is pointless to this story. He can’t understand why everyone refuses to accept just his word that Riker is a bad guy. In one odd scene, one of the characters demands Cain show him proof that Riker was as dangerous as Cain claims, but Cain is unable to do so. After the series hero is told off, Cain exits in defeat, forcing the story to find its hero and protagonist in the guest cast.

In Archives of American Television, Robert Culp discusses his time on CAIN’S HUNDRED and the script he wrote for the other episode (“The Swingerâ€) he appeared in on the series. (Follow the link.)

While during the era of the anthology series, it was not uncommon for a strong guest cast to be featured over the weaker regular lead, but Culp understood the dramatic and long-term needs for any series hero to be the primary star, for him to be in most scenes and be the reason the problem is solved.

Culp’s script for “The Swinger†failed to feature Cain in that way, and despite Culp’s willingness to fix the script, executive producer (“showrunnerâ€) Paul Monash told him not to bother. Culp explained he later learned Monash blamed Richman for the show’s problems. That could explain why the character Cain was virtually emasculated in “The Plush Jungle.â€

CAIN’S HUNDRED ended with thirty episodes completed and was offered in syndication for the fall of 1962.

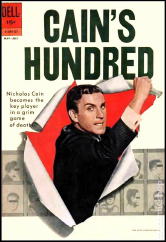

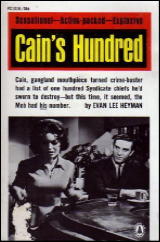

The series featured some interesting tie-ins such as the soundtrack album, a paperback, and a comic book series. The soundtrack by Jerry Goldsmith (with some music by Morton Stevens) was released and reviewed here.

The comic book series lasted two issues, was released by Dell Comics and reviewed here. Popular Library released a mass-market paperback tie-in in 1961, written by Evan Lee Heyman. From the cover blurb it appears the book was based on the origin story.

Peter Mark Richman has continue to have a successful acting career that has lasted over fifty years including supporting roles in LONGSTREET and DYNASTY, numerous guest starring roles in TV, roles in films such as NAKED GUN 2 ½, and voice over work.

Award winning writer-producer Paul Monash would create JUDD FOR THE DEFENSE, develop PEYTON PLACE, and produce the original film version of CARRIE. The Writers Guild of America gave him its Life Achievement award in 2000.

The guest cast featured such talent as David Janssen, Leonard Nimoy, Beverly Garland, Jack Klugman, Robert Duvall, Jack Lord, Robert Vaughan, and Charles Bronson.

Behind the line talent featured writers Daniel Mainwaring, Jim Thompson, David Karp and E. Jack Neuman. Directors included Robert Altman, Sydney Pollack, Irvin Kershner, Buzz Kulik and Boris Segal.

The series was a respectable attempt at doing a quality crime drama such as THE UNTOUCHABLES, but failed due to too many challenges to overcome, from the anti-violence groups to THE GARRY MOORE SHOW to the relationship between star and showrunner.