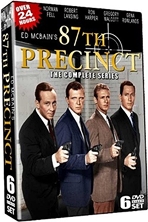

GROVER AVENUE BLUES:

The 87th Precinct TV Series, Part Two

by Matthew R. Bradley.

In Part Two, I continue the episode-by-episode description of the 1961-62 television series, The 87th Precinct, based on the characters created by mystery writer Ed McBain in a long list of very popular police procedurals. If you missed Part One, you can find it here.

◠Interestingly, two episodes were based on works by other authors, with Helen Nielsen adapting “The Very Hard Sell†(12/4/61) from her own story (Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, May 1959). An apparent suicide, a salesman is found shot dead in the car whose prospective buyer (Leonard Nimoy) duped him into transporting drugs during a test-drive; getting wind of this, he tried to make a citizen’s arrest with his own gun, which was then turned on him. Nimoy has little screen time, and his scam is convoluted and far-fetched, making this one of the less satisfying episodes.

◠“Feel of the Trigger†(2/26/62) was adapted — again minus its initial article — from one of Donald E. Westlake’s Abe Levine stories (AHMM, October 1961), collected in Levine (1984); Hawkins gives Abe’s obsession with heart health to Meyer. During a confrontation with a youthful killer, Meyer faces him mano-a-mano and, after subduing him with judo — mentioned frequently in the novels, particularly as a defining characteristic of Det. Hal Willis — suddenly feels fine. Neither of McBain’s minority detectives, African-American Arthur Brown or Puerto Rican Frankie Hernandez, was seen on the show, but this episode gets points for matter-of-factly including black Officer Kendal (Bernie Hamilton) without making an issue of his race.

The show’s original teleplays largely maintained the style and spirit of the books, periodically introducing a lighter tone, as did McBain. Obviously excepting Havilland 2.0, they captured both the personalities of and the dynamics among his characters, stressing the grindingly methodical, sometimes tedious nature of police work; the frequency with which luck and coincidence played an equally large role in the outcome; and the important contributions of the police lab, with which the detectives enjoy a pleasant raillery. Also like McBain, the scenarists populated the squadroom with colorful characters whose vignettes enlivened the proceedings.

◠McBain contributed “Line of Duty†(10/23/61), which he later recycled for Ironside as “All in a Day’s Work†(2/15/68), and uses his character of stoolie Danny Gimp (Walter Burke). Bert sees a theater held up, then kills the perp who fires at him while the other drives away, described as a good boy by all who knew him; when Carella and Kling are given a lead by Danny, Bert freezes and is wounded before Steve shoots the fugitive, who reveals the “good boy†was his accomplice on 14 jobs. Unsurprisingly, McBain does an excellent job of focusing on Kling’s maturation as a detective, struggling to cope with the first time he is forced to kill.

◠Cinematographer James Wong Howe directed Finlay McDermid’s “The Modus Man†(10/16/61), with Havilland and ex-detective Bill Brewster (John Anderson) — now a used-car salesman — recognizing the m.o. of a smash-grab as Maxie Greb’s … but he’s in prison. Carella’s investigating a second-story job, unmistakably the work of Blinky Smith…whose alibi checks; Roger and Kling raid the apartment of Greb’s former partner…who died a week ago. Brewster has microfilmed their m.o. cards, but slips up by telling a victim to shut up while impersonating a crook who can no longer speak.

◠Winston Miller’s “Occupation, Citizen†(10/30/61) concerns a Hungarian refugee (Ross Martin) whose pregnant wife, fearing reprisals, stops him from identifying two mob killers, but after a second killing, he agrees to serve as bait. Immigrants feature prominently in McBain’s precinct, whose population, per Killer’s Wedge, “was composed almost entirely of third-generation Irish, Italians, and Jews, and first-generation Puerto Ricans.†This episode has a valuable lesson in citizenship applicable to all Americans, yet especially these aspiring citizens, with Steve reminding them of their civic duty to their unborn child’s adoptive country.

◠The first of two teleplays by David Lang, “The Guilt†(11/13/61) finds Meyer clobbered by childhood friend Artie Sanford (Mike Kellin), who is bitten by a used-car salesman’s guard dog while trying to make a getaway. Dismissing news reports that it is rabid as a trick, he persuades sometime girlfriend Estelle Vernola (Norma Crane) to transport him in her uncle’s truck. Meyer records Blaney’s warning about the urgent need for treatment, and Estelle plays it for Artie in the back of the truck, prompting a spectacular, eye-rolling freak-out by Kellin before she drives him to the Emergency Hospital, where Meyer awaits.

◠In Lang’s “Ramon†(4/9/62), the eponymous boy (Danny Bravo) can’t stop showing his appreciation after Havilland sends flowers to his mother’s grave, while his father, Villedo Morales (Edward Colmans), is conspiring to assassinate a visiting Central American prime minister, who plans to address his people in front of the precinct house. Roger collects $20 to send Ramon to camp, but Villedo, reconsidering when Havilland touts ballots over bullets in another of the show’s solid moral lessons, pulls Ramon from camp to leave town. Fearing he won’t see Roger again, the boy eludes him, his destination obviously the 87th, and Villedo, arriving just before the speech, fingers the conspirators.

◠In Anne Howard Bailey’s “My Friend, My Enemy†(11/27/61), a woman lies to alibi her son, Andrew Mason (Dennis Hopper), who strangled a classmate in the park, and the suspicious Carella has an undercover Kling befriend him. Daniels urges caution when Bert risks the jealousy of Claire — killed off in Lady, Lady, I Did It! (1961) — to make a double date with two policewomen. With Hopper providing an early taste of the manic energy he brought to Apocalypse Now (1979), the unbalanced youth learns that Kling is a cop, and threatens him with his own gun before being disarmed.

◠The first of four scripts by Donn Mullally, “Run, Rabbit, Run†(12/25/61) marks Paul Genge’s debut as Lt. Jim Burns (Peter Byrnes in the novels). The only surviving witness to testify against an executed mobster, Toots Brendan (Alfred Ryder) is betrayed when he tries to sell his interest in “the operation†to help finance his disappearance. Not above deception, Steve tells secretary Yvonne English (Barbara Stuart) — who is sweet on Toots — that he’s been killed, so she reveals her duplicitous boss’s address, enabling the detectives to intervene.

◠Pete Rugolo and Jerry Goldsmith, respectively, pinch-hit on Mullally’s “Man in a Jam†(1/8/62) and Katkov’s “Step Forward†(3/26/62) — both directed by Twilight Zone vet James Sheldon — for Goldsmith’s protégé, Hawaii Five-O legend Morton Stevens; all three scored Thriller, another Hubbell Robinson Production. “Jam†concerns a man who claims he killed his fiancée during a drunken black-out, in reality a premeditated crime for which he forged I.O.U.’s from her to fictitious other men of whom he was supposedly jealous. Unfortunately, the Byzantine nature of his scheme threatens credulity.

◠A somewhat whimsical departure, “Step Forward†finds the underpaid Carella accepting a job as a bank’s security chief; he chafes at the symbolic post, humoring rich clients, but provides two of them with valued advice. Kling drops in as the Carellas and Meyers enjoy cocktails, nicely showing how the detectives remain friends off-duty, and when he gets a tip on a payroll robber, the three head out to pick him up. Despite the extra money and the prestige of his own staff, Steve admits policing is “more fun,†his new job obviously forgotten as they question the suspect.

◠Kling asks local baseball hero Larry Brooks (Michael Dante) to start a baseball clinic to get the local kids on the right path in Mullally’s “Idol in the Dust†(4/2/62). Larry tries to extricate his parole-violating brother Joe (Al Ruscio) from a crooked poker game, and in the ensuing mêlée, Joe pushes one crook out the window to his death; for their mother’s sake, Larry confesses to involuntary manslaughter, upholding the code of silence. This makes him a hero to the local punks, but when Bert assembles them and the clinic kids to see Larry, Carella brings Joe, who agrees to take his own rap, advising them to avoid his fate — guidance that could also serve viewers well.

◠In Mullally’s “The Last Stop†(4/23/62), Mike Power (Victor Jory) is scapegoated after being shot in a taxi by Stu Tobin (Bern Bassey) while the latter silences a squealer, then asked by long-ago partner Burns to run out the retirement clock at “the Eight-Seven.†In an effective performance by Jory, he rubs everyone the wrong way, but his hunch is borne out that a rash of crimes by a shotgun-wielding woman is a hoax. Correctly confident that he won’t be recognized, Stu brazenly sits beside Powers in a bar; as Mike accosts him to return a lighter left behind, a departing Stu misconstrues and shoots it out, but Powers survives again and is retired, effective immediately.

◠Written by Alfred Hitchcock Presents mainstay William Fay, “Main Event†(1/1/62) has Meyer’s pal “Sonny†Fitzgerald (Brad Weston) beset by a booby-trapped punching bag and spiked rubbing solution. The culprit is revealed as gofer Bobo Felix (Arch Johnson), an ex-pug who was used up and thrown away by — and is trying to frame — a notoriously crooked rival manager, resenting Sonny’s success. But the subtleties of Bobo’s plan seem at odds with his punch-drunk persona, making this another problematic episode.

◠In Jonathan Latimer’s “Out of Order†(1/22/62), ex-con Jerry Curtis (Charles Robinson) is suspected of bombing a phone booth when his construction foreman reports a dynamite theft, and although cleared when another blast goes off during questioning, he decides to cash in, believing it’s useless to try going straight and voicing a familiar complaint about persecuted parolees. Bombing a café and emptying its register, he adds theft to the m.o., but Meyer finds evidence in the phone company’s crank letter file that helps identify the original bomber, who denies the thefts. Jerry is apprehended after shooting a man with a gun concealed in his “bomb†while bluffing a betting parlor.

◠Rik Vollaerts received a story and shared script credit (with Raphael Hayes) on “The Pigeon†(1/29/62), with Peter Falk well suited to the typical oddball role of Greg Brovane. Coincidentally, the 87th entries So Long as You Both Shall Live (1976) and Jigsaw (1970) were respectively repurposed into his Columbo episodes “No Time to Die†(3/15/92) and “Undercover†(5/2/94). Aspiring to the big time like his father, Greg has been hypnotized to think he made it, confessing to two killings in a supermarket heist he didn’t pull and fingering three nonexistent accomplices.

◠James Bloodworth also had story and shared script credit (with Collins) on “A Bullet for Katie†(2/12/62), the new bride of cop Bill Miller (Ed Nelson). Gantry (Harold J. Stone) excoriated Bill when left by his wife while in prison, but a co-worker recants his alibi for Katie’s shooting after Gantry refuses to be blackmailed into concealing factory theft. Providing extra nuance, Bill is well portrayed as abrasive and hot-headed, gunning for vengeance when he learns that Gantry is about to be picked up, but just in time, a boy admits wounding Katie while playing with an “unloaded†gun borrowed from a friend.

◠In Sheldon’s “Square Cop†(3/12/62), written by Robert Hardy Andrews, Otto Forman (Lee Tracy) is suspected after the weapon that killed his partner is identified as his, reported stolen, and the description of the wounded perp matches his estranged son. When Burns says, “he fell down, failed, right in his own family,†Steve replies, “that happens to a lot of fathers,†alluding to Larry Byrnes, revealed as an addict and murder suspect in The Pusher. Tracy brings a nice gravitas to the role, dramatizing the classic duty vs. family conflict, with the viewer uncertain which way he leans until he decks the youth, who had tried to force his father’s help.

◠Collins wrote the last episode, “Girl in the Case†(4/30/62), in which a millionaire dies after dictating a will to stenographer Cheryl Anderson (Janis Paige), offered $100,000 to swear that he was not of sound mind. It’s revealed that an ex-member of his law firm had planned to split $3 million left to a family member in a previous will. Havilland wines and dines Cheryl, but is chagrined to learn that she plans to marry the man’s ne’er-do-well son, who might actually become something with her help; this makes her a nicely complex character, seeming far less like a mere gold-digger.

The “conglomerate hero†device aided the scenarists in mixing and matching characters from any book after Killer’s Choice to circumvent Roger’s absence. A Casanova, McBain’s Hawes often bedded any babe he saw, an aspect that not only was downplayed on the show but also ruled out the married Carella and Meyer and engaged Kling, leaving Havilland his default stand-in, e.g., romancing Cheryl. Roger’s literary successor, Andy Parker, fought with Steve over racist remarks to Hernandez, who is slain in See Them Die (1960) while trying to prevent a besieged killer’s becoming a barrio martyr.

The 87th has since had mixed success onscreen, although as with noir authors David Goodis and Cornell Woolrich, French filmmakers, e.g., Claude Chabrol, favored these romans policiers. With Burt Reynolds (Carella), Jack Weston (Meyer), and Tom Skerritt (Kling) relocated to Boston, Richard A. Colla’s Fuzz (1972) was a misfire, despite being adapted by McBain-as-Hunter. His 1968 novel had brought back the Deaf Man — Yul Brynner, like Vaughn one of The Magnificent Seven (1960) — and Det. Eileen Burke (aka McHenry; Raquel Welch); the latter, unseen since The Mugger, became a major character starting with Ice.

— Copyright © 2023 by Matthew R. Bradley.

Editions cited —

The Mugger: Warner (1996)

Killer’s Choice: Avon (1986)

All others: Signet (1974, 1975, 1976, 1977, 1989)