A MOVIE REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

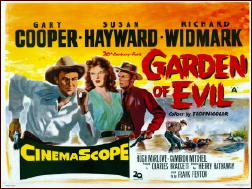

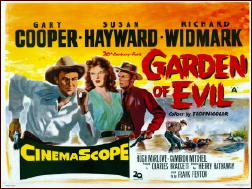

GARDEN OF EVIL. 20th Century-Fox, 1954. Gary Cooper, Susan Hayward, Richard Widmark, Cameron Mitchell, Hugh Marlowe, Rita Moreno. Screenplay: Frank Fenton; director: Henry Hathaway.

“If the earth was made of gold, men would still die for a handful of dirt.”

When is a western not a western?

When it’s an adventure film, like The Treasure of Sierra Madre and this, Henry Hathaway’s Garden of Evil, even though it is set in the classical western period after the Civil War and features gunmen and Apaches.

Gary Cooper, a soldier; Richard Widmark, a gambler; and Cameron Mitchell a gunfighter too fast with a gun and his temper are aboard a ship headed south when they arrive too late in a small Mexican fishing town to make their ship and have weeks to wait until the next ship is due.

We never learn exactly what they are fleeing, but it is clear from the subtext of the film that what they are seeking — each in their own way — is a new beginning, redemption. None of them expect to find it in this sleepy little fishing village where the most excitement would seem to come from a flirtatious girl (Moreno) in the cantina, and a jealous vaquero.

But today is the day Susan Hayward shows up, a desperate American who says her prospector husband has been trapped in a mine and she needs help to save him — help she will pay for. But there are no takers. Hayward and her husband have been prospecting an old Spanish conquistador mine, one in the interior in a remote valley guarded by an almost stone age band of Apaches. No local will follow her for any amount of money. The valley is haunted, and damned.

But Cooper, Widmark, and Mitchell will, and the vaquero. They can be bought for money, the lure of gold, and the beauty of a woman. They are men who hold those things more dearly than life.

The tension rises as they set out toward the valley. The vaquero is trying to mark the trail (not knowing Hayward has destroyed his markers), and Cooper has to beat Mitchell half to death and humiliate him after a near rape.

Nor is Cooper fooled by Hayward’s desperation to save her husband. He has seen through her as clearly as he has Mitchell or the vaquero. She is guilty because she doesn’t love her husband, afraid he will die having gotten himself killed trying to prove he was worthy of her. Like the others, she is seeking redemption for herself as much as rescue for her husband.

Cooper can read them all because he knows himself. All but Widmark, the enigmatic gambler who talks too much too easily and says so little. Widmark’s ability to play both hero and villain plays a major role here, because neither Cooper or the viewer knows exactly where the cards will fall with him.

There is also a fairly subtle sense in the film that Widmark’s character is seduced almost as much by Cooper’s honor and sense of himself as he is by Hayward or the gold. Widmark will use the same almost homoerotic subtext in his role opposite Robert Taylor in The Law and Jake Wade.

It’s a mark of his qualities as an actor that the manages it without seeming the least weak or effeminate, He simply conveys that his character finds something missing in himself — or something he fears is missing in himself — in the strong silent and competent Cooper.

Finally they reach the valley and enter along a narrow cliff trail. The Apaches let them in with no trouble, though they watch them from every shadow. They will not let them out as easily.

They find the husband, Hugh Marlowe, alive, half mad, tormented by the Apaches who have made a game of watching him die, in pain, and bitter at Hayward who he blames for his own weakness and whom he half feared would abandon him, half feared would return and make him face again that he is a weakling, a failure, and unworthy of her..

Meanwhile Mitchell and the vaquero have gold fever. Only Cooper and Widmark know their problems have just begun.

Once they rescue Marlowe from the mine they set out to leave the valley.

One by one the Apaches pick them off. The vaquero, Mitchell, and finally Marlowe who sacrifices himself to save Hayward, earning in death what he could never find in life.

But Cooper, Hayward, and Widmark make it to the narrow cliffs in a running battle. There is one spot where a single man with a rifle could hold off the Apache while the others escape. They cut cards. Widmark stays behind.

Cooper gets Hayward out, but has to go back. He says it is because Widmark cheated at the card draw, then admits: “I was wrong about him, I have to tell him.” He returns in time to find Widmark wounded and dying with a quip and laugh on his lips. As the setting sun turns the valley to gold, Cooper says bitterly: “If the earth was made of gold, men would still die for a handful of dirt.”

He rejoins Hayward and they ride away.

Veteran director Henry Hathaway directed Garden of Evil from a literate script by Frank Fenton. The score is by Bernard Herrmann and does much to lift the film above its western origins; it is one of his best works.

The location cinematography by Milton Krasner is stunning, and few films of the era use technicolor as effectively. The location shooting looks like no other western of the period.

Like many simple adventure films Garden of Evil has things to say. At the time it must have seemed like just another good adult western, but through the looking glass of time we can see that the rare skills of the cast, director, script, score, and cinematography came together in ways that surpassed its origins.

It may seem a simple adventure story about men and a woman and their desires, dreams, hopes, and fears, but there is more here.

This is the type of film they mean when they say they don’t make ’em like that anymore. It has the thrills of a Saturday matinee or a serial, but it also has things to say about all of us, about why men and women risk their lives for dreams and for love.

Within the confines of a western it has something to say about loss, dreams, loyalty, and what those things can cost and are ultimately worth. Cooper is a man who has lost his dreams and regains them. Widmark, a man who never let himself dream, finds a woman worth desiring and a man worth dying for. Hayward’s obsession costs four men their lives, but she saves her soul and redeems herself as a woman.

Like Adam and Eve, she and Cooper are reborn, but in innocence this time, emerging from what an old padre called the garden of evil.

“If the earth was made of gold, men would still die for a handful of dirt.” Or for a woman’s love, honor, and a chance at redemption.