Wed 10 Jun 2009

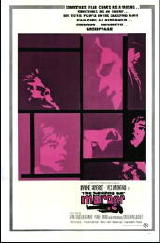

A Movie Review by David L. Vineyard: THE SLEEPING CAR MURDER (1961).

Posted by Steve under Mystery movies , Reviews[6] Comments

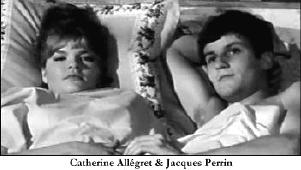

THE SLEEPING CAR MURDER. Seven Arts, 1961. Simone Signoret, Yves Montand, Pierre Mondy, Jean-Louis Trintignant, Jacques Perrin, Michel Piccoli, Catherine Allégret (debut), Charles Denner. Based on the novel Compartiment Tueurs (aka The 10:30 From Marseille) by Sébastien Japrisot. Director: Costa-Gravas.

Before he made his mark as a political director with leftist leanings, Costa-Gravas made his debut with this slick little police thriller about the hunt for a mad killer.

The police are represented by Inspector Grazziano (Grazzi) played by Yves Montand and his younger partner Grabert played by Jean-Louis Trintignant, whose involvement begins with the discovery of a body on the Phoce’en, the 10:30 morning train from Marseille, and an attractive young woman who has been murdered.

We are almost instantly in Maigret country, but to Costa-Gravas’s credit, he establishes his own visual style and technique rather than rely on memories of films of Simenon’s novels. There is nothing leisurely or casual about Montand and Grabert. They are real policemen who chew on antacids, smoke too many cigarettes, and take endless notes, and almost from the top they are up to their necks in it, because before they have finished sorting the first corpse there’s a second waiting for them. The weariness in Montand’s lined doggedly handsome features becomes a character in itself.

Police and authorities are seldom sympathetic characters in Costra-Gravas’s films, so it comes as a shock how much this film identifies with its put-upon policeman heroes.

They are decent men with lives outside the office, and would rather do just about anything than have their superiors down their necks as they face an increasing number of corpses and a possibly mad killer.

Costa-Gravas relies less on flashy camerawork and more on storytelling in this one, with atmosphere to spare, thanks to cinematographer Jean Tournier’s brilliant camera work, the film’s quick pace and the well-done action scenes.

Signoret and the rest of the cast are fine, as might be expected, and thanks to staying close to Japrisot’s tight cinematic script, the film is both suspenseful and a good mystery well-solved.

That said, you would do well to find a copy of the film with subtitles and avoid the awful dubbed version I first saw.

Costa-Gravas became a world wide sensation with his next film, Z, but his increasingly leftist films became more propaganda than entertainment, though his one American film Missing, with Jack Lemmon and Sissy Spacek, was highly thought of. Since then politics outstripped the film-making in too many of his later works. Montand also appeared in Z, State of Siege, and The Confession all helmed by Costa-Gravas, forming one of the French cinema’s most productive teamings.

Sébastien Japrisot is one of the more familiar French writers on this side of the Atlantic, thanks to the films of his works, including his original screenplays for Rider on the Rain and Goodbye Friend, and adaptations of many others like Lady in the Car With Glasses and a Gun and One Deadly Summer. Most recently the 2004 film of his novel A Very Long Engagement was an international hit.