Sun 20 Mar 2022

It’s been a year since I posted this link on my blog. Take a 30% discount on the prices you see here, which is how they’re priced on Amazon:

https://mysteryfile.com/Books/MysteryPB.html

Sun 20 Mar 2022

It’s been a year since I posted this link on my blog. Take a 30% discount on the prices you see here, which is how they’re priced on Amazon:

https://mysteryfile.com/Books/MysteryPB.html

Sat 19 Mar 2022

CLIFTON ADAMS – The Desperado / A Noose for the Desperado. Stark House Press, trade paperback, 2017. // The Desperado. Gold Medal #121, paperback original, 1950. // Noose for the Desperado. Gold Medal #683, paperback original, 1957.

First heard about this via George Tuttle’s defunct website defining noir and suggesting some titles:

He says there: “The Desperado by Clifton Adams … though a Western, this novel is a landmark of early Gold Medal noir. Set in Texas during Reconstruction, the story traces the subtle transformation of Talbert Cameron from battler of injustice to outlaw.â€

Never before having thought of westerns as part of the noirboiled genre, this way eyeopening and provided this bibliomaniac with a whole new reading source to plunder.

Though westerns seem like they are 1800’s rather than 1940’s, the genre started around the same time as noirboiled crime, involved many of the same writers, and contains many of the same themes and styles as the Hammett’s and Chandler’s whose bibliographies I’d exhausted.

The lone gunman, the town harlot, and the marshall of the western are fairly transposable to the hardboiled detective, Jim Thompson psycho, and the femme fatale. The town always corrupt.

The Stark House edition I read has the following Donald Westlake quote on its cover:

“A compact, understated, almost reluctant treatment of violence, first introduced me to the notion of the character adapting to his forced separation from normal society.†Sounds like the Desperado’s the Parker template.

Onto the books themselves (in a recent read (Blue of Noon) a female character says: “Get to the point. I never listen to prefaces.â€).

Talbert (“Tallâ€) Cameron is around 18 years old, with a temper, in small town Texas during reconstruction. His folks have a little homestead, raise cattle and horses. It’s all real homey.

But then Talbert punches a carpetbagging cop who insults the local ladies, and he’s due to do time on the work gang.

He ain’t going.

He takes off, and when the cops beat his dad to death when his dad refuses to squawk of Tall’s whereabouts, all bets are off.

Tall comes back, exacts his revenge, and from there on out he’s a desperado.

It’s well written. It’s hard. It’s dark. It’s boiled.

The Desperado is quite good. Quite archetypal. Innocence lost. Young love. Honor. Revenge. Betrayal.

And like the typical hard-boiled detective, he’s got an ethos. He doesn’t steal. He only kills in self-defense.

And then comes the sequel: A Noose for the Desperado.

First of all: Spoiler alert: No Noose. Not even the suggestion of a noose.

He takes over a western version of Poisonville for no apparent reason than greed.

Now, for some unexplained reason, the Desperado has lost his morals. Or at least traded them for ambivalence.

He’s like Yogi Berra’s old saying that if you see a fork in the road, take it.

He steals. And then he decides that money doesn’t matter. He uses people. And then he looks after them. And then he doesn’t.

One of the main Aristotelian virtues is constancy. It’s a virtue all the great heroes have.

The Desperado has it in the first novel and loses it in second.

While he escapes the noose, we do not.

Sat 19 Mar 2022

ELLERY QUEEN – The Origin of Evil. Little Brown, hardcover, 1951. Paperback reprints include: Pocket #926, 1953; #2926, 1956. Signet, 1972. Harper Perennial, 1992. Also one of the three novels included in the omnibus volume The Hollywood Murders (J. B. Lippincott, hardcover, 1951).

Ellery returns to Hollywood and finds reports of its death premature, but a new Hollywood, to be sure. Revenge is apparently the motive for a series of mysterious threats to a pair of business partners; one of them dies of fright.

It is the other, confined to a wheelchair, who believes he has worked out the murder scheme, but this time the real murderer is even more clever.

The pseudo-Tarzan living in a tree is the most remarkable character, one most remembered. There seemed to be a bit more lenient attitude toward sex in this story than expected. Ellery falls in love with one unworthy; Paula Paris is not mentioned.

The series of threats has a hidden significance, as well as the first threatening note. Was EQ’s presence a factor? Lack of evidence keeps justice from triumphing completely, not quite satisfying.

Rating: ***

Sat 19 Mar 2022

THOMAS B. DEWEY – Deadline. Mac #13. Simon & Schuster, hardcover, 1966. Pocket 55002, paperback, 1968. Carroll & Graf, paperback, 1984. Presumably expanded from the short story “Deadline” appearing in Sir!, August 1968.

For a hardboiled PI detective novel, which this one definitely is, it’s a little different from most hardboiled PI novels – but probably not different enough to be unique, one of a kind. Mac – that’s the only name we ever know him by in all 17 of his novels – has been hired by a panel of psychologists and social workers, not to prove a young boy on death row is innocent – he’s already confessed – but to prove that he’s legally insane, and to persuade the governor to issue a stay of execution.

Most of Mac’s cases take place in the down and dirty streets of Chicago. (The second and last two take place in Los Angeles.) Deadline takes place in the small farming community of Wesley, Illinois. Dominating the town is the local John Deere dealer, and since it was his daughter who was brutally murdered, the man most certainly does not want Mac to stop the execution.

Mac does not have much to work with. His “client†is socially challenged and it is difficult for him to give any coherent information about the day of the girl’s killing. Her best friend, still in high school, has an emotional disorder. Mac’s only ally in Wesley is Miss Adams, a teacher in the local high school, and since she is dating the girl’s father, her help is only reluctantly provided at best.

Mac is beaten up at least once in this one, and chained up in a barn so he can’t do any damage to the case against the boy about to be executed. The title, Deadline, is certainly an appropriate one. Mac’s efforts to figure out what exactly did happen come down to the last minute. Somewhat unfortunately, the clue that’s the key one is rather an obvious one. (I spotted it, after all.)

There’s a hint of attraction between Mac and Miss Adams, but it’s clear by book’s end that anything more than that is not going to happen. That’s an ending that quite probably happened to him more than once.

Fri 18 Mar 2022

THE NOVEMBER MAN. Relativity Media, 2014. Pierce Brosnan, Luke Bracey, Olga Kurylenko, Bill Smitrovich, Amila Terzimehic. Will Patton. Director: Roger Donaldson.

The concept is compelling; it’s the execution that’s flawed. That’s pretty much how I would describe The November Man to anyone who wanted a brief, succinct answer to the question: “What did you think of the movie?â€

Adapted from Bill Granger’s espionage thriller There Are No Spies, the seventh entry in the author’s “November Man” series, the movie is grounded in the realities of the post-Cold War world and has a solid, reliable lead in Pierce Brosnan. But it ultimately ends up being nothing more than a stunningly average spy film, one that relies on twists and turns that are – for those familiar with the genre, at least – clearly visible from miles away.

The movie opens at a fast clip, with the viewer immediately thrust into the action. CIA operative Peter Devereaux (Brosnan) and junior partner, David Mason (Luke Bracey) are in Montenegro and are on an assassination mission. Things don’t go according to plan. Brosnan is hit. And a young child is wounded, perhaps fatally.

Years pass and we find a retired Devereaux (the spy in retirement trope!) living in Lausanne, Switzerland. That’s when his former boss, John Hanley (Bill Smitrovich) shows up, asking Devereaux to take on one last mission: to extract a CIA asset from Russia by the name of Natalia Ulanova. She’s currently working for Arkady Fedorov, a former Russian Army general who is on his way to becoming president of the Russian Federation and has information that supposedly could bring Federov crashing down.

That’s where the twists and turns begin. Can Devereaux really trust that he is taking on a legitimate mission or has he been set up? Things get interesting when we learn that Federov apparently kidnapped and sexually assaulted a young girl during the Second Chechen War.

Things get more interesting when we learn that this girl may still be alive and that she may have been witness to a meeting between a CIA Agent and Federov that set into motion that deadly conflict.

Most of the film follows Devereaux as he attempts to make sense of a confusing, fast-moving situation. He not only finds himself at odds with Mason, his former protegee, but having to protect a social worker (Olga Kurylenko) who supposedly knows the whereabouts of Federov’s victim.

Now don’t get me wrong. I like Roger Donaldson’s work and consider his thriller, No Way Out (1987) one of the best, if consistently underappreciated, spy films ever. But here he feels as if he was just going through the motions. While there’s not necessarily anything wrong with the direction, there’s nothing particularly captivating about it either. The action sequences, filmed on the streets of Belgrade, are about as ordinary as can be. If it weren’t for Brosnan, one wouldn’t really pay much attention to them at all.

Wed 16 Mar 2022

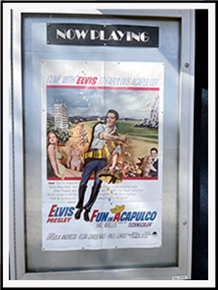

FUN IN ACAPULOCO. Paramount Pictures, 1963. Elvis Presley, Ursula Andress, Elsa Cárdenas, Paul Lukas, Larry Domasin, Alejandro Rey. Producer: Hal Wallis. Director: Richard Thorpe.

I realize that movies such as this one don’t turn up on this blog very often, but other than the fact that Elvis is in it, it marks a significant milestone for me. It’s the first movie I’ve seen in a theater in almost two and a half years. It was the matinee film shown at the New Beverly Theater in Hollywood last Sunday. The New Beverly is owned by Quentin Tarantino and specializes in retro films from 60s through the 80s, many of them prints coming from Tarantino’s own collection, such as this one. The poster below is the one on the sidewalk in front of the theater as you entered.

The movie was a big hit in its day, but to call it fluff from today’s perspective would be exaggerating by a factor of ten. The plot has something to do with Elvis’s character, the object of affection of two women in competition for his sole attention, and not much more than that — Elsa Cárdenas as a lady bullfighter, and Ursula Andress as the assistant social director at the resort hotel in Acapulco where Elvis has a combined job as a lifeguard and (of course) a singer.

I didn’t recognize any of the songs, but the teen-aged girls who came in hordes to see this movie in 1963 surely did. Besides Elvis, the other star attraction, the one aimed for the guys whose girls came to see him and were forced to come along, was of course Ursula Andress, this being the very next film she made following her bombshell appearance as Honey Ryder in the James Bond movie Dr. No. They made for an interesting couple on film. One can only wonder how they may have gotten along in real life.

I probably would never have sat down to watch this on TV, but it served its primary purpose very well. A movie in brilliant technicolor on a big screen with lots of people in it singing and dancing and just plain having a good time – and all that was only a bonus. It just felt great to be back in a movie theater again!

Wed 16 Mar 2022

IT HAPPENED IN BROAD DAYLIGHT. Switzerland,-West Germany-Spain, 1958. Original title: Es Geschah am Hellichten Tag. Heniz Ruhmann, Michel Simon, Gert Frobe, Maria Rosa Salgado, Anita Von Ow. Screenplay by Friedrich Durrenmatt (his story), Hans Jacoby, and Director Ladislao Vaja.

This offbeat German noir film is based on Swiss novelist Friedrich Durrenmatt’s novel The Pledge, but takes off from the main conceit of that novel in some interesting directions of its own as a powerful suspense film about the nature of obsession, guilt, and the lengths a man will go to accomplish his ends.

It opens in the woods outside a small town where Jacquier (Michel Simon), a peddler, discovers a child’s body and flees to town and the local pub where he calls chief investigator Matthai (Heniz Ruhmann) who once treated him well.

Matthai is on his last day before a new important job in Jordan, but calls out the authorities and they are guided to the body of the girl by Jacquier who in short order becomes the chief suspect, Matthai only saving his neck from angry locals when he points out that all who claim they saw Jacquier in the woods are just as much suspects as he is.

Matthai isn’t so sure about Jacquier’s guilt though. One of the girl’s friends shows him a picture the victim drew of her friend ‘the giant†a man she met in the woods and befriended. Surely a fairy tale, but …

When Jacquier commits suicide under the relentless police interrogation Matthai is not sure he was guilty but the police are happy to close the case and that of other girls who died similarly over the last four years.

Not Matthai though. He continues to investigate and begins to put together a picture of the killer, a man henpecked by his bitter Mother who strikes out in frustration with a razor against the children he has targeted.

Following a trail of clues Matthai closes in on the killer, but knows he can never trap him without the ideal bait, and in a small town he finds it in a lonely little girl like the ones killed before and her widowed mother, Frau Heller and Annemarie (Maria Rosa Salgado and Anita von Ow) . Taking a job at a gas station and living with the mother and daughter he begins to lay his trap.

By this point we know the killer is one Schott, a henpecked giant (Gert Frobe) who lives with his cruel mother.

Vajada skillfully inter-cuts scenes of Schott and Matthai almost encountering each other, Matthai filling Schott’s tank with gas as Schott watches Annemarie in his side mirror, the two men passing on the road, all building tension as Annemarie and Schott, her “Magician†meet in the woods and the pressure on Schott from his mother pushes him closer to action and the straight razor in his bath he has used before.

Even with Matthai finally seeing Schott he still has to catch him in the act, but that means using Annemarie as bait, something he cannot do because he has come to care for the child.

Matthai plants a doll dressed like Annemarie in the woods like the little girl Jacquier found, but Annemarie escapes from her room and heads for the woods to meet with her “Magician…â€

Heinz Ruhmann was a beloved German star in the period perhaps best known here for his films playing Georges Simenon’s Maigret that were dubbed in English and shown on American television in the Sixties. His humanity, gentle screen presence, and surprising strength made him a popular Maigret, but also lend themselves to the drama in the far more complex Matthai, a rather cool character whose cold calculations are complicated by his feelings for a lonely child.

This is supposedly the role that got Gert Frobe the role of Auric Goldfinger in the James Bond film. Around this time he would be introduced in more familiar form to American audience as the police inspector in Fritz Lang’s 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse and its sequel. A hero of the War who smuggled many Jews out from under the Nazis, Frobe would have a successful career in the West in films such as Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines and Bloodlines despite not speaking English.

Durrenmatt’s The Pledge was filmed with Jack Nicholson in a form much closer to the book. The author was a noted playwright and novelist perhaps best known among Mystery fans for his Inspector Barlach novels, one of which became a film with Jon Voight and Robert Shaw. His novels and plays often deal with mystery and suspense, but seldom in a straightforward manner. He is far more interested in the psychology of his characters and the paradox involved than straight detection or suspense alone. He’s an extremely important writer, if not always an easy one, and this does justice to his work.

That this film captures so much of the feel of his work despite having to play to a somewhat more standard model is one of its strengths. Evocatively filmed and well acted, particularly by Ruhmann, Simon, and the mute Frobe it plays like the best of film noir with all that implies about flawed wounded human beings, and how they sometimes destroy each other. It is a powerful and disturbing film that can jolt more with the image of a dead child’s hand emerging from a pile of leaves than a hundred gory horror films, a single cry of rage from Frobe when Schott realizes he has been tricked tells more than pages of dialogue about this repressed monster.

I can’t recommend this one enough. It’s hardly a lost film, but one that doesn’t get the kind of attention many of its French and American cousins do in the genre, and that is a shame. You really owe it to yourself to find it on YouTube (there are several versions, but the one by Old Movies B/W and Colour Simonbartbull has English subtitles and is a clear looking print).

See this one. It is a classic.

Tue 15 Mar 2022

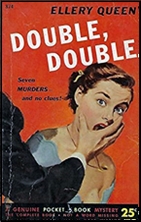

ELLERY QUEEN – Double, Double. Little Brown, hardcover, 1950. Pocket #874, paperback, 1952. Dell, paperback, 1965. Ballantine, paperback, 1975, 1979. Also published in a Signet double novel edition, and as The Case of the Seven Murders (Pocket, paperback, 1958).

A series of anonymous envelopes sent to Ellery Queen from Wrightsville filled with clippings from the local newspaper there is what first piques the well-known mystery writer’s interest. This is followed up by a visit from the daughter of the local “town drunk,†who has mysteriously disappeared and is assumed to have met with foul play and to be dead, his body swallowed up by quicksand at the bottom of a cliff.

The girl is somewhat of a “bird child,†living barefoot and alone in a shack at the edge of a swamp. (You should not be surprised to learn that her name is Rima.) Before the two of them return to Wrightsville, Ellery plays Pygmalion with her, furnishing her with new clothes, up-to-date hair styling and the like.

Wrightsville is a small town somewhere in New England, with small town stores and small town businesses, a local doctor who still makes house calls, and a place Ellery has a strange affinity for, with at least three previous cases having taken place there. The townspeople know him well.

Three deaths have already occurred, one suspicious, the other two not. Before the book is done, a total of seven have taken place. I suppose it does no harm to tell you now that the pattern that Ellery discovers connecting them comes from the nursery rhyme that begins “Rich man, poor man…â€

This being the first Ellery Queen novel I’ve read in a while, I was caught by surprise at how chaotic his detective stories could be: swirling winds of surrealism and the unknown. Added to the mix are suspicion, doubts, small town nostalgia, and karma. The final solution, the one that unravels the mystery at the end, is, in fact, greatly dependent on the latter. Events have happened that even the killer could not control.

The detective work is superb – it is utterly fascinating to read a novel in which so many threads of the story could be so knotted up and elusive – then unsnarled so the pieces all fit together. Except … except for the fact that in an Ellery Queen story the people do not act or react as real people would. They are in a sense both naive and artificial, and they do things that real people would not do – especially the killer, as hard as Ellery Queen the detective does his best to explain his or her thinking.

I do not mean to suggest that this is a bad thing, except perhaps for present day readers who do not understand the worth of a pure puzzle story. You start to read an Ellery Queen novel, and you will find yourself at once in an Ellery Queen world governed by Ellery Queen rules and Ellery Queen ways of thinking.

Opinions on this may vary, but I found myself enjoying this return visit to the world of Ellery Queen, a visit I’ve delayed for far too long. Shame on me.

Mon 14 Mar 2022

Points of interest online, perhaps:

◠A recent blog (only three entries, so far, unless I’m missing others) is called Crime Film Hub Daily, with links to news and reviews of, guess what, crime films online.

â— From a follower of this blog named Greg Karber: “I’m a huge fan of fairplay mysteries, and I’ve channeled that affection into an interactive murder-mystery logic-puzzle game called Murdle.â€

https://gtkmysteries.com/murdle

“I’m trying to share it with people I think might be interested. The mysteries get more complicated and difficult throughout the week, like the crossword, so if today’s too easy, just wait for tomorrow’s!â€

â— From Bob Byrne, a regular contributor to the Black Gate website:

“Back when the world blew up early in 2020, I began writing about a thousand words a day, about Archie Goodwin’s life, locked in the brownstone with Nero Wolfe.

“I wrote about 42,000 words over 45 days, posting them nightly at the Wolfe Pack FB page.

“I’m posting them weekly now at Black Gate, giving them a more permanent home. Here is this week’s entry – I’m up to Day 38:

“Each installment includes all my prior Wolfe musings and stories, including a solo Archie adventure that won a Wolfe Pack contest last year.”

Mon 14 Mar 2022

THE TEXAS RANGERS. Paramount, 1936. Fred MacMurray, Lloyd Nolan, Jean Parker, and Jack Oakie. Screenplay by King Vidor, Elizabeth Hill, and Louis Stevens, from the book by Walter Prescott Webb. Directed by King Vidor. Currently streaming on YouTube.

A trio of desperadoes get separated while fleeing from a posse. Two of them join the Texas Rangers as cover, and gradually find themselves becoming committed to the Ranger mission, while the third forms a new gang and continues on his thievin’ murderin’ way, and if you can’t tell what develops….

Despite the formulaic plot, this is far far from routine, thanks to Vidor’s assured direction and the performances from the leads. Until he hooked up with Disney and My Three Sons, MacMurray always lent a kind of equivocal edge to his roles that contrasted uneasily with his bluff good looks, and it makes him perfect as the bad guy turned hero (for now). Oakie’s good-for-little bravura makes a fine comedy relief, and Nolan’s big-city look suits his character just fine.

But it’s Vidor’s sensitive handling of stock situations and his flair for action scenes that lifts Rangers out of its cliche’d roots.

F’rinstance, there’s a bit where the Rangers are trapped on a cliffside, holding off angry Apaches down below. A few of the more ambitious Native Americans climb up above and start laboriously rolling boulders down at the Rangers. Vidor’s smooth way of cutting (The boulders come at intervals, thundering down the near-sheer wall like a cannon shot, as the rangers claw their way up the cliff to stop them) from long-shots, to medium exteriors, to studio “exteriors†propels the scene to epic proportions.

Then, in quieter moments, the emotional resonance he puts into the scene where Nolan and Oakie have it out — Oakie’s braggadocio melting as he realizes how dangerous his old pal has become, Nolan losing control of himself, and visibly enjoying it — has stuck with me since I was a kid, and followed me into my dotage.

Jimmy Stewart called moments like these “Pieces of time.†I call it fine movie-making and great fun.