Wed 4 Nov 2020

Music I’m Listening To, Selected by Jonathan Lewis: THE GRATEFUL DEAD “I Know You Rider.” Live, 1970.

Posted by Steve under Music I'm Listening ToNo Comments

Wed 4 Nov 2020

Tue 3 Nov 2020

MIAMI VICE. “Milk Run.†NBC, 04 January 1985 (Season 1, Episode 12.) Don Johnson, Philip Michael Thomas, Edward James Olmos. Writer: Allison Hock. Director: John Nicolella.

If by twelve episodes into the first season, viewers hadn’t realized that they were a long way from Cabot Cove territory, they certainly would have after watching this one. Murder, She Wrote had begun the year before, and while the two shows were never on opposite each other (that I know of), half the country, I’m sure, would have been watching that one, while the other half found a lot more to watch in this one.

There’s not time for a lot of byplay between the main characters in “Milk Run.†The story begins at the beginning and plays through with no digression to the end. It is assumed that viewers knew who Crockett and Tubbs were when they started watching, and if they didn’t, it was certainly easy enough for them to catch up.

The main story line involves two young boys who have come down to Miami to turn they life savings into real money. Unfortunately their plan of action requires dealing with a smuggling ring, with one of the two traveling to Columbia, picking up a religious statue filled with drugs, and bringing it back into this country.

Which is not at all a good idea.

While the skies in Miami are generally clear and sunny in this one, there is more than the usual sense of darkness and suspense than I think there were in most crime-related television series at the time. The setting, the music, the clothes, all mesh together in a perfectly choreographed tale of crime gone wrong that’s at one time very simple but also very complicated.

Even better, it’s a story that easily be shown today with very little updating needed.

Tue 3 Nov 2020

MICHAEL ROBOTHAM – When She Was Good. Cyrus Haven/Evie Cormac #2. Scribner, hardcover, July 2020; paperback, July 2021. Setting: Contemporary England.

First Sentence: Late Spring. Morning cold. A small wooden boat emerges from the mist, sliding forward with each pull on the oars.

In this follow-up to Good Girl, Bad Girl, the mystery of Evie Cormac continues. Found hidden away in the hidden room off the bedroom where a man was tortured and killed, the question remains as to whether he was her kidnapper, or her protector. Although the press are still curious, someone more sinister is after the information, and Evie, while psychologist Cyrus Haven, plagued with monsters of his own past, teams up with Sacha Hopewell, the former Constable, who found Evie, to try to protect her.

There are several elements needed for a memorable book and description/sense of place is one. Robatham has that well in hand— “The air outside smells of drying seaweed and wood smoke, and the distant hills are edged in orange where God has opened the furnace door and stoked the coals for a new day.”

It is useful to have already read Good Girl, Bad Girl. However, Robotham not only fills in the backstory of Evie, but includes new information. The way in which Cyrus’s background is conveyed is brilliantly understated yet establishes an important link. We also learn much more about Terry Boland, the man whose body was found in the house where Evie was hiding.

This is a dark book. Robotham has written a clear and strong example of the impact of abandonment. Then he changes the pace with a surprising plot twist and an example of Edie’s ability as a truth wizard — one who can tell when others are lying.

There are observations which cause one to pause and are relevant to today— “The real power belongs to the people who control information… Individuals who can suppress stories, fix problems, spin news, and plant false information.” —and make us think of current situations— “…is a classic sociopath, who seeks power and influence rather than fame.

Where others notice the beauty in the world, he sees only how it could benefit him. Relationships are designed to further his own interest. It’s not about loving or hating but about duplicity and deception and his own corrupt lust.” Intended or not, and although the author is an Australian living in England, the story cannot help but make one think of current events.

When She Was Good is a complicated story with unique characters and a satisfactory ending. Slow in places, it picks up with well-done twists.

Rating: Good Plus.

Tue 3 Nov 2020

FOUR STAR PLAYHOUSE “Bourbon Street.†CBS, 09 December 1954 (Season 3, Episode 11). Dick Powell, Beverly Garland, William Leicester, Clarence Muse, Ed Platt. Writer: Richard Carr. Director: Roy Kellino.

In many ways this noirish 25 minute play has more going for it than many a shoot ’em up, ultra violent neo-noir two-hour extravaganza in full color does today. Dick Powell is in full hard-boiled tough guy mode in this one, as a piano player who has managed to make his way out of the quicksand life of New Orleans, only to return when he learns that the girl he loved has committed suicide.

He blames the young hoodlum who stole the girl from him, and the only thing on his mind is revenge. Along the way he meets another girl (Beverly Garland) who pleads with him to give it up and take her along with him. Does he? Not a chance. He walks out, closing (but not slamming) the door behind him.

Right into an out-and-out beating and a twist that maybe you will see coming, but I didn’t. It’s beautifully set up, though, and if you decide to watch it (video clip provided), I hope you agree. I liked this one.

Mon 2 Nov 2020

We never met but once we came close to having a conversation. It was the late Seventies, and I was in La Jolla to attend the annual meeting of the University of California library board on which I served. He lived in the same town, and I was given his phone number and tried to call him one evening. His wife answered, saying he literally couldn’t talk with me: he’d just gotten out of the hospital after surgery for throat cancer. That was as close as I came to contact with Jonathan Latimer.

If you watched PERRY MASON regularly during its first-run years on TV (1957-66) you saw his name in the credits again and again. Erle Stanley Gardner is said to have called him the only writer who really mastered the art of writing MASON scripts. Between the second of the show’s ten seasons (1958-59) and its last (1965-66) he wrote a total of 32 hour-long scripts for the series: 25 originals, 6 adaptations of Gardner novels and, I kid you not, one script based on a short story by Hugh Pentecost. But that was the tail end of his career. Our main concern here is with his beginning.

He was born in Chicago on 23 October 1906 and named Jonathan after his great-great-grandfather, who had served on George Washington’s staff during the Revolutionary War. After graduating from Knox College (Galesburg, Illinois) in 1929 he returned to Chicago and worked as a crime reporter for the Herald-Examiner and the Tribune, meeting several celebrity gangsters while on the job. He was in his late twenties when he began writing novels, the first six published by Doubleday Crime Club, five of them featuring a private detective and somewhat under the influence of the overwhelmingly dominant author of that genre during the 1930s, Dashiell Hammett. The first of these was MURDER IN THE MADHOUSE (1935).

It opens inside an ambulance with a guy named William Crane in handcuffs and being transported through upstate New York to a private sanitarium for well-to-do mental cases. No sooner has he arrived than he seems to establish why he’s there by claiming to be a famous detective, no less in fact than C. Auguste Dupin.

The kicker is that he really is a detective, a PI hired to infiltrate the sanitarium and look into the claim of one of its residents, a dotty old lady who loves to knit, that a box containing negotiable bonds worth $400,000 — a huge amount back in the days when gasoline cost 11 cents a gallon — has vanished from her room. (If you’re wondering why she kept that fortune unprotected, well, didn’t I tell you she was dotty?)

The inmates of this nameless loony bin, whom Crane quickly meets and begins to interact with, include a fellow who thinks he’s Abraham Lincoln, a wolf man who prowls around the grounds on all fours, another guy who hasn’t spoken a word in four years, and several more, perhaps a few too many. The doctors in charge are at each other’s throats, most of the nurses are predatory sexpots in starched whites, and the staff is mainly composed of weirdoes like the religious maniac who acts as night watchman.

As per the title, there is a murder in the madhouse, four of them in fact. The local law enforcement people are idiots, but there are genuine clues to follow and Crane does a neat job of reasoning in between hearty slugs of the local applejack.

Like Hammett’s Continental Op, Crane is not a lone wolf but works for a big agency, its head being an unseen character known as the Colonel (later expanded to Colonel Black). Unlike the Op, he doesn’t narrate his own cases. But Latimer’s style consists mainly of simple declarative sentences such as we find in Hammett’s THE MALTESE FALCON and THE GLASS KEY. And Crane, like Nick Charles in THE THIN MAN, drinks gallons of booze.

What Latimer contributes to these established ingredients is a sardonic gallows humor whose like is not found in Hammett. We don’t find a great deal of this in MURDER IN THE MADHOUSE but it soon becomes prominent.

Like Sam Spade in THE MALTESE FALCON and Ned Beaumont in THE GLASS KEY, Crane was onstage at every moment of MADHOUSE, but his next case features several scenes without him. In HEADED FOR A HEARSE (1935) he’s still based in New York but spends almost all of his time in Chicago, racing against the clock to save an innocent man from the electric chair. Joan Westland was found shot to death in her locked apartment, to which only she and her estranged stockbroker husband Robert had keys.

There’s no murder weapon on the scene but ballistics tests establish that the fatal bullet came from a rare British pistol of World War I vintage. Robert owned such a pistol, which has mysteriously vanished. The people in the apartment below Joan’s testify that they heard a shot at a time when by his own admission Robert was visiting her.

He’s convicted and sentenced to death, but shortly before his execution he receives a note, apparently from a criminal prowling in Joan’s apartment building at the time of the murder, who claims he can prove Robert’s innocence. With less than a week before his date with the chair, Robert brings in a sleazy criminal lawyer named Finklestein, who in turn brings in Crane.

As in MURDER IN THE MADHOUSE, our PI spends many hours guzzling the sauce as more bodies pile up but somehow manages to get sober for the denouement two hours before Westland is to be fried. The plotting is tight and the solution to the locked-room puzzle pretty simple by John Dickson Carr standards but rather ingenious, although the tie-buying clue and the telephone-call gimmick still leave me scratching my head.

The most powerful scenes take place in the death house at the beginning and end of the novel. In Chapter XI comes a pure specimen of Latimer’s gallows humor as we get a description of a Bascom Wonder Funeral, “including a handsome Lincoln hearse, three automobile loads of mourners (we can augment your mourners if you desire), the use of our private chapel with the $8000 Barton organ and the Golden Isle Quartette,†plus “a choice of five distinctive caskets.†All for the low low price of $217!

Those not at home in the geography of the Windy City can have a lot of fun with a map tracking Crane’s taxicab journeys back and forth across the Chicago River from Point A to Point B in search of the vanished pistol. But I must warn potential readers that, its merits as a whodunit to one side, HEARSE is a generous anthology of political incorrectness, with epithets taboo in the 21st century strewn all over the landscape: Heeb, sheeny, Chink, dago, even the six-letter word which I’d be screamed at as a racist if I repeated.

All this is okay when coming from the mouths of characters of the Archie Bunker ilk but not so okay in the early pages of Chapter IX when it seeps into the third-person narrative. Small wonder that HEARSE didn’t appear in paperback until more than twenty years after its hardcover publication and then, like another Latimer novel we’ll discuss eventually, only in bowdlerized form (Dell pb #D1896, 1957).

Two years after its publication HEARSE became the basis of the first in Universal Pictures’ 8-film Crime Club series. THE WESTLAND CASE (1937) was directed by industry old-timer Christy Cabanne (1888-1950) from a screenplay by Robertson White. Preston Foster played Crane, with Frank Jenks as his sidekick Doc Williams.

I can’t recall ever seeing this picture but from what I’ve read on the Web (including Dan Stumpf’s review for Mystery*File) it seems to have followed Latimer’s plot fairly closely, although I’m willing to bet that none of the racial and ethnic epithets with which the novel abounds survived into the movie.

In his first two books Latimer tried his hand at the whodunit laced with gallows humor but the next one was his masterpiece in that vein. In THE LADY IN THE MORGUE (1936) New York is still Crane’s base but while temporarily in Chicago he receives a wire from his boss, Colonel Black, directing him to hang out at the Cook County morgue and try to identify the body of an attractive blonde who apparently hanged herself in her cheap hotel room right after taking a bath and disposing of all her shoes. (As we learn later, the firm has been hired by members of a wealthy family who are afraid the dead woman might be the clan’s rebel daughter.)

But the body is stolen from the morgue during the wee hours and the night attendant bludgeoned to death. The hunt for the missing corpse soon leads to the murder of an undertaker and a wave of wacky-gruesome incidents as Crane and his sidekicks Doc Williams and Tom O’Malley encounter a pair of feuding gangsters, a gaggle of luscious blondes, and an alcoholic bulldog in whose company they conduct a midnight search of a cemetery for another (or is it the same?) vanished female body.

Crane finds little time to sleep but plenty to guzzle — including a slug of embalming fluid unaccountably kept in a bottle of Dewar’s Scotch — as he and his buddies lurch from one cockeyed venue to another, perhaps the most vivid being the dime-a-dance joint where all the girls dance in their underwear and the morgue where Crane wraps himself in a sheet and, posing as an embalmed corpse, waits for the murderer.

The solution is chaotic and what passes for reasoning leaves much to be desired, but what a madcap epic! In his entry on Latimer in 20th CENTURY CRIME AND MYSTERY WRITERS (3rd ed. 1991) Art Scott calls it “a genuine mystery classic….grotesque and hilarious at the same time, a masterpiece of black comedy.â€

That may be too thick a coat of encomium, but if you’re going to read any Latimer at all it’s gotta be THE LADY IN THE MORGUE. Note for the triviac: In the first edition the drug best known as pot is rendered as marahuana, a spelling I’ve never seen before, but in Crime Club’s hardcover reprint of 1953 it’s changed to the form we all know and love.

Under the novel’s title but without much resemblance to its anarchic plot, THE LADY IN THE MORGUE (1938) became the third entry in Universal’s series of Crime Club movies, with Preston Foster returning as Crane. This one was directed by Otis Garrett, who had served as film editor on THE WESTLAND CASE, with screenplay by Eric Taylor and Robertson White.

A copy of the movie accessible on YouTube shows us that the man claiming to be the vanished corpse’s brother was portrayed by Gordon Elliott, who later in 1938 started going by Bill or Wild Bill Elliott and, under these monickers, quickly become a notable star of B Western flicks.

No novel under Latimer’s byline appeared in the year after MORGUE but a novel by Latimer did. THE SEARCH FOR MY GREAT-UNCLE’S HEAD (1937) was published as by Peter Coffin, who also serves as first-person narrator (Peter Nebuchadnezzar Coffin, to give him his full name). Anyone who had read an earlier Latimer novel was unlikely to have been fooled by the new byline since the detection is done by none other than Colonel Black from the Crane series.

In his ENCYCLOPEDIA MYSTERIOSA (1994) William L. DeAndrea called it “a weird hybrid of country house cozy and hard-boiled effects.†That’s good enough for me. Sometime soon I’ll explore Latimer’s three final PI novels — two about Crane, the third not.

Sun 1 Nov 2020

THE BROKENWOOD MYSTERIES “Blood and Water.†Prime, New Zealand. 28 September 2014 (Season 1, Episode 1).. Neill Rea (Detective Senior Sergeant Mike Shepherd), Fern Sutherland (Detective Kristin Sims), Pana Hema Taylor, Cristina Ionda, and a large remaining ensemble cast. Writers: Tim Balme (also creator) & Philip Dalkin. Director: Mike Smith. Currently streaming on Acorn TV via Amazon Prime Video.

When an elderly man who has been grieving the death of his wife for several years is found drowned below the bridge he came to on the same date every year, the immediate assumption is that he committed suicide. But why then, has Auckland almost immediately sent Det. Sgt. Mike Shephard (Neill Rea) to the small town of Brokenwood to investigate?

With the head of the small local police force stepping out of the picture in deference to Shepherd, it is up to Detective Kristin Sims to deal with Shepherd’s brusque and often unorthodox approach to police work, but (to no viewer’s surprise, including mine, nor should it) she gradually and begrudgingly learns that Shepherd really does know what he’s doing.

As Mike Shepherd, Neill Rea is really the star of the show, which has been on now for six seasons of four two-hour episodes each. (It comes as no surprise that at the end of the first episode Shepherd has decides to stay on, having come to appreciate the advantages of living and working in a small town filled with quirky characters.) He is overweight, scruffy, has an unspecified number of ex-wives – he admits to three, maybe four – but possesses a quick mind that is always working.

The detective work is better than average, the setting is often beautiful, but it’s the people in the stories that follow that will have me coming back often, I’m sure.

Sun 1 Nov 2020

BLACK ORPHEUS. Dispat/Tupin, Brazil, 1959. Original title: Orfeu Negro. Breno Mello, Marpessa Dawn, Lourdes de Oliviera, and Ademar da Silva. Written by Marcel Camus & Jacques Viot, based on the play Orfeu da Conceição by Vinicius de Moraes, which is itself an adaptation of the Greek legend of Orpheus and Eurydice. Directed by Marcel Camus. Winner of Oscar® for Best Foreign Language Film at the 32nd Academy Awards in 1960.

Costumes, celebration, death and voodoo — could any film be more fitting for Halloween?

Yes, I know it’s paternalistic, simplistic, and slowed down by too many overlong dance scenes, but the sheer vibrant energy and romantic urgency of the thing sweeps me along with the uncluttered story-line: A beautiful young Eurydice comes to Rio at Carnaval, fleeing Death. She is temporarily rescued by Orpheus, but in the end, he must seek his love in the next world.

The simple story is conveyed with memorable visuals. The shanty-towns of the city seem to hang on cliffsides as precarious as the pursuing death, the costumes glitter and shimmer in the sun, and Death itself (athletically portrayed by Ademar da Silva) moves with a coiled grace that makes me wonder if the creators of Spider-Man (whoever they may be) were inspired by his lithe and lethal acting.

Just as striking is Orpheus’s descent into the underworld, wandering empty corridors until a benign Janitor — Charon, with a broom instead of a barge pole — guides him down a staircase of infinite emptiness to a hellish voodoo world where the myth must play itself out once again.

Like me, you may be used to thinking of Halloween movies in terms of Karloff, Lugosi, Universal and Lewton. Or you may be of a generation that equates Horror Movies with serial slashings and CGI monsters. But I found Black Orpheus the equal of these, and in its own way, better than most.

Need more? Actors Breno Mello and Marpessa Dawn, the star-crossed lovers of the film, died within weeks of each other, and Ademar da Silva died on the same day as the composer of the film’s justly-celebrated score:

Sat 31 Oct 2020

PHANTOM OF THE OPERA. Universal Picures, 1943. Nelson Eddy, Susanna Foster, Claude Rains, Edgar Barrier, Leo Carillo, J. Edward Bromberg. Jane Farrar, Frank Puglia, Stefan Geray, Fritz Feld, Miles Mander, Fritz Leiber, Barbara Everest, Hume Cronin. Screenplay by Eric Taylor & Samuel Hoffenstein. Adapted by Hans Jacoby as John Jacoby, based on the novel by Gaston Leroux. Directed by Arthur Lubin,

When Universal sought to capitalize on the film that first made them a great studio in the silent era thanks to Lon Chaney Sr., they spared no expense. Like the original silent film, this version of the oft-told tale features lavish sets and costumes, a cast of some of the finest faces in Hollywood, including the ever popular Nelson Eddy, and one of the finest actors in Hollywood in the lead as the Phantom, Claude Rains.

To this, add an original operatic score, cinematography by W. Howard Greene and Hal Mohr, and stunning Technicolor.

It is too bad that somewhere along the way they forgot the mystery, the horror, terror, and for the most part Eric, the Opera Phantom.

They remembered the opera though.

Here we have Erique Claudin (Claude Rains), a violinist in the orchestra of the Paris Opera who secretly loves Christine (Susanna Foster), stand-in to vainglorious diva Biacarolli (Jane Farrar), so much so, he has secretly been paying singing master Leo Carillo to train her, But when Claudin loses his job, he needs money, so he takes the music he has written to publisher Miles Mander who dismisses him.

In his despair and desperation Claudin kills Mander accidentally and scars his own face with acid, fleeing to the sewers which lead beneath the Opera house, there beginning his reign of terror against Biancarolli so that Christine may take her place.

And all that is well enough if Rains and his Phantom did much more than run around in a costume borrowed from Lamont Cranston, casting a few half-hearted shadows and mostly lurking offscreen unseen and unheard, while we get a parade of some of the finest character actors in Hollywood in what mostly plays as a light opera with way to much comic business between baritone Nelson Eddy and policeman Edgar Barrier fighting over Christine, and far too many operatic numbers.

The famous chandelier scene is well-handled, and there is a well done chase between Eddy and Rains in the rigging above the stage, but mostly this generates virtually no mystery, no terror, and no horror, no Masque of the Red Death. Even the famous scene of Christine unmasking the Phantom is tossed off with no suspense or style.

Oh, yeah, he’s disfigured. Ho, hum.

Rains is largely wasted. The fine cast has to hold a thriller with no thrills and a mystery with no mystery there between too many musical numbers there only to justify Nelson Eddy being cast in the film.

Just about everything you expect of the Phantom is missing. There is no Gothic atmosphere, no labyrinth sewers beneath the Opera, no menacing shadows, and the violence, when it comes is all done off camera ending anti climatically with Claudin fleeing through the large well lighted halls of the opera dressed like an escapee from Mad Magazine’s Spy vs Spy.

Seldom in film history has more money been spent to less effect.

That’s a pity, because the makings were there for a fine film of the classic, if everyone hadn’t been so overcome by the class of the project they forgot it was also a tale of murder, madness, terror, horror, and obsession.

Sat 31 Oct 2020

For my Halloween movie viewing this year, I revisited two films that I had previously watched and reviewed for this blog. United Artists’ White Zombie (1932), reviewed here, and Universal’s Werewolf of London (1935), reviewed here.

Both are films that I had enjoyed and appreciated. Both also were movies that I had the chance to see screened in 35mm here in Los Angeles, the former at UCLA and the latter at Quentin Tarantino’s New Beverly Cinema.

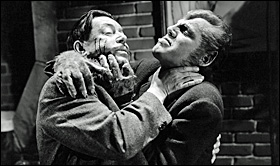

White Zombie, in which Bela Lugosi plays the ultra-sinister Haitian villain named Murder Legendre, was the first proper zombie movie released by a Hollywood studio. (How zombies went from creations of Haitian voodoo to that of viruses and outbreaks merits a whole different discussion). And Werewolf of London, starring Warner Orland and Henry Hull, was the first proper werewolf movie.

The movies are, in some ways, clunky by today’s standards. (One might say they were even clunky for their time.) But that doesn’t really matter. While Werewolf of London is a bit more stylish and grounded, both movies have a timeless, nearly dreamlike quality to them.

They are both, in many ways, fairy tale romances as well. It wasn’t until I watched both consecutively that I realized that, fundamentally, both movies are about doomed love triangles. In both movies, a man ends up sacrificing himself so that the woman he loves could be with her one true love.

Sat 31 Oct 2020