FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

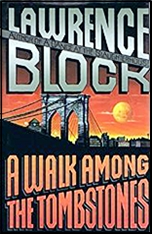

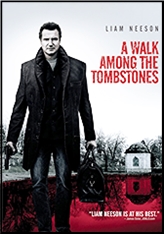

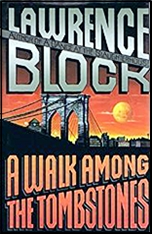

I am satisfied that Lawrence Block, who turns 82 this year, is the finest living writer of private-eye novels, and that his protagonist Matthew Scudder is the late 20th-early 21st century counterpart of Philip Marlowe and Lew Archer. In previous columns I’ve explored the earlier Scudder novels, going back to his debut in 1976. This month we take the character to near the end of the century which first saw him come to life on the page.

***

If A TICKET TO THE BONEYARD (1990) and A DANCE AT THE SLAUGHTERHOUSE (1991) were the most powerful novels in the series to date, one of the main reasons was that they pitted Scudder against genuinely satanic adversaries. So does the next book in the series. A WALK AMONG THE TOMBSTONES (1992) opens with a scene presented in third person, and for a few minutes we wonder if we’re reading about the unlicensed PI we’ve come to know so well. But Matt and first-person narration return after two pages, and the rest of Chapter 1 alternates between the two modes. It’s as if Block were determined to make the third-person scenes more vivid and, yes, more graphic than they could possibly have been in the form of dialogue between Scudder and others.

The tale these scenes tell is of the kidnaping of 24-year-old Francine Khoury from the street outside the ethnic market in Brooklyn where she’d been shopping. Her husband Kenan, a prosperous narcotics trafficker, receives phone calls from the abductors demanding a million dollars for her return. They settle on $400,000. After the ransom is paid, Khoury gets another call, telling him his wife is in the trunk of a Ford Tempo parked illegally at a fire hydrant around the corner. He and his brother Peter check and find her: cut up into cutlets and wrapped in plastic bags.

Peter, who isn’t in the drug trade but is a recovering junkie and alcoholic, recommends that Kenan hire Scudder. Once committed to the case, and thanks to his police contact Joe Durkin, Matt learns that Francine wasn’t the first woman to be mutilated and murdered by criminals using the same modus operandi. Eventually he finds one young woman who escaped alive, although only after the perps performed an obscene parody of the novel and movie SOPHIE’S CHOICE, making her decide which of her breasts they should cut off. With the help of two teen-age computer hackers brought to him by his young black buddy TJ, he obtains the numbers of the various pay phones on which the murderers called Kenan Khoury.

Then comes another kidnaping, the victim this time being the adolescent daughter of a Russian drug dealer, and the inevitable race to save her from sexual violation, mutilation and death. The first part of the climax, packed with tension but without a moment of onstage violence, takes place near midnight in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery, site of the exchange of the girl for a million dollars; the second, at the serial killers’ house.

In A TICKET TO THE BONEYARD Scudder killed a psychopathic monster in cold blood but, unwilling to make a habit of the practice, declines to take part in Khoury’s vengeance, which is best described by one of the Latin phrases tossed around earlier in the novel by an attorney recalling the legalisms in that language that he learned in law school. The phrase: lex talionis. Later Khoury describes the scene for Scudder — so graphically it makes him vomit. As might many readers.

***

Block apparently realized that if all subsequent Scudders involved combat against satanic adversaries they’d soon become indistinguishable. In the next book in the series he tried another experiment in minimalism. The basic story of THE DEVIL KNOWS YOU’RE DEAD (1993) occupies at most 25% of the novel’s 316 pages, the murderer never appearing onstage for a moment and not even his name mentioned until page 292.

Scudder and Elaine casually meet Glenn Holtzmann, a yuppie lawyer working at a large-print publishing house, and his pregnant wife Lisa. For some reason, or perhaps just on cop instinct, Scudder is turned off by the man. Lisa loses the baby, and one evening about two months later her husband is shot to death with four bullets, three in the body and the fourth in the back of the neck as a coup de grâce, while standing in front of a pay phone — not inside a booth, they don’t exist anymore — on Eleventh Avenue almost within sight of the high-rise condo on West 57th Street where he and Lisa lived.

Within 24 hours a near-homeless street person and Vietnam veteran is arrested for the murder, the shell casings from the four bullets found inside his stinking Army jacket. He doesn’t remember whether he committed the crime or not. His younger brother, another recovering alcoholic, hires Scudder to make sure of the facts one way or the other. The job brings Matt in close contact with Lisa, who calls on him for help when she finds a strongbox containing several hundred thousand dollars on a closet shelf, and it soon becomes apparent that Glenn Holtzmann was obtaining huge amounts of cash from a mysterious source.

In the course of the investigation Scudder and Lisa begin an affair. There’s not a moment of violence or menace in this novel except for a brief interlude when Scudder takes on another case, this one pitting him against a sadistic psycho whose ilk we’ve seen in other Block novels. Several interesting chapters follow Scudder as he methodically probes Holtzmann’s past, but in the end the truth is revealed to him by a transsexual hooker and Scudder and Elaine move in together while Matt seems poised to continue his affair with Lisa.

This is one of those Block novels you read not so much for the story as for the extraneous incidents surrounding the story, my favorite being the one on page 97 where Scudder recounts a mob hit in which four innocent people sitting at a table on one side of a restaurant were blown away and the four intended targets on the other side were left untouched. “The shooter, it turned out, was dyslexic, and turned left when he should have turned right.†Moral? “Everybody makes miskates.†Or, as Hammett put it unforgettably, we live while blind chance spares us. This incident, like several but not all the others, is thematically related to the core story: I won’t say how.

Like other Scudder novels, THE DEVIL KNOWS features guest appearances by the usual regulars: Mick Ballou, TJ, Matt’s former lover the sculptor Jan Keane, his AA sponsor Jim Faber, the cop Joe Durkin, the black albino Danny Boy Bell. One of these doesn’t make it to the last page, and though Block doesn’t intend the death to be a surprise, on general principles I won’t say who. I do get the impression that for a while Block seriously considered making Ballou the murderer and writing him out of the series, but if so, clearly he had second thoughts. I prefer the Scudders with a stronger story and a satanic adversary but, like millions of others, I can’t stop reading these books.

***

If Block was bothered by the lack of sufficient core story in THE DEVIL KNOWS YOU’RE DEAD, he solved the problem in the next Scudder, A LONG LINE OF DEAD MEN (1994), by pitting his protagonist against another serial killer, although this one is not a sadist but something of a philosopher. One of the current members of a 31-man club which may have been founded centuries ago, and whose only purpose is to meet for dinner every year on the first Thursday in May and and commemorate the members who have died since the birth of the club’s present incarnation in 1961, comes to Scudder when it dawns on him that there are only fourteen members still alive.

To put it another way, there have been an unusual number of member deaths in the past 30-odd years: some unsuspicious, like that of the young man who was killed in Vietnam in 1966; some clearly from natural causes, others apparent accidents or suicides, four clearly murders. This premise requires that many of the characters, being dead, never appear onstage, but Block with superb skill makes them all but come back to life as Scudder investigates how they died—and whether a member of the club has been devoting years of his life to killing off his fellow members. (No, this is not a tontine, where the last man standing gains millions, nor is it a trust as in my novel BENEFICIARIES’ REQUIEM where every death in the family increases the share of the survivors. If there is a serial killer, he can’t be motivated by money.)

Eventually, and largely by trial and error, Scudder identifies his adversary, with whom he’s had a most unusual relationship before this moment, and the game of cat and mouse takes a new turn. Some of the murders have been exceptionally brutal, particularly one whose details Scudder learns from his NYPD friend Joe Durkin: the wife of a murdered club member who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time “was garroted with a strip of wire. Her head turned purple and swelled up like a volleyball….She had a fireplace poker thrust up her vagina and well into the abdomen.â€

When one of the club members (a controversial criminal defense lawyer notorious for getting guilty monsters acquitted) assures Scudder that the legal system will never be able to bring the killer to justice, the only option left on the table is extra-legal vengeance. In this case vengeance takes a unique and not too plausible form, but at least it circumvents the Mike Hammer type of justice we found in novels like A TICKET TO THE BONEYARD.

On the personal side, Scudder is still a sober alcoholic regularly attending AA meetings, living with Elaine and sleeping now and then with Lisa. The usual regulars make their expected appearances, not only Joe Durkin but Mick Ballou and TJ and Scudder’s AA sponsor Jim Faber. Also appearing, and in a major role, is one we have seen in Block novels many times before: Mister Death. Even before the first word of the book, we get to read William Dunbar’s poem “Lament for the Makaris†with its incessant refrain Timor mortis conturbat me (fear of death terrifies me). The theme is reinforced by the huge number and variety of deaths we encounter (although there’s hardly a moment of onstage violence in the entire book) and dialogue about death. “Cancer, heart attacks, all those little time bombs in your blood vessels. Those are the things that scare you.â€

The speaker will die violently a few chapters after he says this. Scudder: “[M]an is the only animal that knows he’ll die someday. He’s also the only animal that drinks.†Mick Ballou: “But do you think there’s a connection?†Scudder: “I know there is.†Like so many other novels in this powerful series, A LONG LINE OF DEAD MEN makes it understandable that so many are now calling all PI fiction noir.