Fri 25 Oct 2013

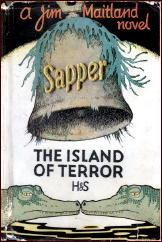

A Review by David L. Vineyard: H. C. McNEILE [SAPPER] – The Island of Terror: A Jim Maitland Adventure.

Posted by Steve under Characters , Reviews[2] Comments

H. C. McNEILE – The Island of Terror: A Jim Maitland Adventure. Hodder & Stoughton, UK, 1931, as by “Sapper.” US title: Guardians of the Treasure, Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1931.

The hour was two of a summer’s morning; the scene—somewhere in Hampstead. And as he walked down the steps into the drive he pondered for the twentieth time on the asininity of man, — himself in particular. Why on earth had he ever allowed that superlative idiot Percy to drag him to such a fool performance?

There sounds the true voice of the 1920’s thriller, a bit of P. G. Wodehouse, a touch of Arabian Nights (at least the Stevensonian type), and the social conscience of a gnat. But if you can get past 21st Century guilt and self loathing from the left and the right and read this as entertainment, as it was meant to be read, there are pleasures to be found, certainly in H. C. McNeile (Sapper)’s two books featuring Jim Maitland, a far less frothy and blathering fellow than Bulldog Drummond or Tiny Carteret.

Maitland is the puhka sahib type, more likely to haunt seedy waterfront bars in seedy waterfronts from Uraguay to Singapore than London’s stuffy gentlemen’s clubs. Maitland was a type — Somerset Maugham or Conradian gentleman in foreign ports. Roger Conway in Lost Horizon was one of the breed, and in real life they had names like Rhodes, Raffles, Gordon, and Burton, and nicknames like the White Rajah — who once haunted popular fiction.

It was the Jim Maitland’s George MacDonald Fraser’s Harry Flashman so deftly skewered. They were the backbone of that empire the sun never set on. They might be ruthless, certainly racist, but they did things like end slavery in the Sudan, find the source of the Nile (yes, I know that was Speke), crush piracy in the Malay Peninsula, and destroy thugee, a criminal conspiracy whose victims numbered in the millions — and often with surprizingly little help. Many were a good deal like Sapper’s description of Maitland:

…And if some of the stories grow in the telling it is hardly to be wondered at, though in all conscience the originals are good enough without any embroidery.

Talk to deep-sea sailors from Shanghai to Valparaiso; talk to cattlemen on the estancias of the Argentine and after a while, casually introduce his name. Then you will know what I mean.

“Jim Maitland! The guy with a pane of glass in his eye. But if you take my advice, stranger, you won’t mention it to him. Sight! his sight is better’n yourn or mine. I reckons he keeps that window there so that he can just find trouble when he’s bored. He’s got a left like a steam hammer, and he can shoot the pip out of the ace of diamonds at twenty yards. A dangerous man, son, to run up against, but I’d sooner have him on my side than any other three I’ve yet met.”

Thus do they speak of him in the lands that lie off the beaten track …

By the 1950’s he had gotten a bit sodden with gin and tonic, had a bit of malaria, and seemed more interested in trysts with women he should have left alone, but the lure was still there.

Maitland first appeared in a collection of novellas that ended with him saving a virginal girl from a fate worse than death from a nasty Egyptian chap (he was a spy too), and seemed headed toward the kind of blissful country manor life Dornford Yates’ Boy and Berry and Jonah were always departing for a bit of smuggling and humorous rescues of fair damsels in the Anthony Hope Ruritainian mode. Maitland was made of sturdier stuff, just read the story “The Temple of the Crocodile†from Jim Maitland. Hugh Drummond would have run home to Phyllis to change his nappies.

But come Island of Terror Maitland seems to have forgotten his former love, and he’s soon off for adventure in the wilderness. And wild it is.

Of course Miss Draycott is an English rose in full bloom, and Maitland’s not blind behind that monocle. And someone did take a shot at him in the dark.. On to Chapter Two … After consulting with a respectable businessman Maitland once saved from the gangs of Marseilles — before respectability caught up with him — Maitland gets on to Clem Hargreaves who knows everything worth knowing about the underworld.

It takes a while to get out of England headed toward Lone Tree Island, “south of Santos.†And quoting Robert Service to Judy Draycott we’re off: Have you ever stood where the silences brood/ And most of the horizons begin … Splendid stuff. Bulldog Drummond never got anywhere more exotic than Switzerland — and even then he never got near a Alp.

There’s a blind dwarf (the villain), a tribe of intelligent white apes (I suppose some of Tarzan’s cousins from the Great Apes immigrated), a little golden idol, a crude temple, a near run thing, a lost brother (a Balliol man I’ll wager — it always is in these things — never trusted one myself when I was at Oxford — nice respectable Christ’s College man you know), a ruby the size of a hen’s egg, and a hint lone Tree Island holds more mysteries …

Well, not Sapper, because having married off another hero we never hear from Maitland or his monocle again. But, if you only know McNeile from Drummond and Ronald Standish, get ahold of Jim Maitland and Island of Terror. Critic Richard Usborne called Maitland McNiele’s finest work in The Clubland Heroes, and I’m inclined to agree.

And next time you delve into the latest Rollins, Cussler, or Bell adventure you may understand why they were all McNeile fans.

Note too that “sometimes o’ nights,†that’s the true voice of the era, Haggarded Haggard’s, Kipled Kiplings, and Servicable Service, an age when adventure didn’t have to be accompanied by a social conscience, and you could enjoy some Godforsaken hell hole in the back of the beyond without wanting to pave the roads and build a school.

Those are noble things to do in real life, but just once I’d like to do a little armchair adventuring without the nagging voice of social awareness. I suppose someone would have tried to rescue those white apes, make them learn how to read, put shoes on them, and hook them up to the Internet.

If I wanted real life I’d be outside doing it, not inside getting vicarious thrills from our own breed of Imperial heroes like Dirk Pitt, Painter Crowe, or Alex Hawke … Somehow I think a “pane of glass†would improve any of them.