Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

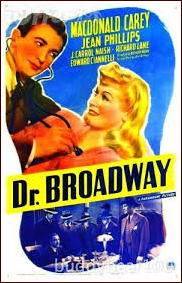

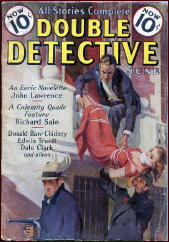

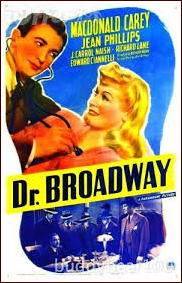

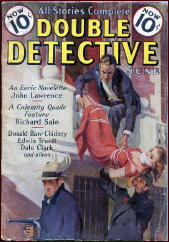

DR. BROADWAY. Paramount, 1942. Macdonald Carey, Jean Phillips, J. Carroll Naish, Richard Lane, Eduardo Ciannelli. Joan Woodbury, Gerald Mohr, Warren Hymer, Olin Howard, Frank Bruno, Sidney Melton, Mary Gordon, Jay Novello. Screenplay: Art Arthur, based on the short story “Dr. Broadway” by Borden Chase in Double Detective Magazine (June 1939). Directed by Anthony Mann.

Dr. Broadway … Specialist in Heart Trouble … and Lead Poisoning

The lights of old Broadway are flashing over Times Square, neon and traffic, crowds and honking horns, and a pretty girl on a ledge.

So what’s new?

Not much for Dr. Timothy Kane, Dr. Broadway (Macdonald Carey), a smooth taking GP who was raised and sent to college by the people of the Broadway streets when his much loved newspaper man father died. On this night there is a pretty blonde girl on a ledge (Jean Phillips — Ginger Rogers stand-in — and really nice legs I might add) and his old pal Detective Sergeant Pat Doyle (Richard Lane) bets him a ten spot he can’t talk her down.

Of course she has no intention of jumping. It’s a publicity stunt — but she didn’t know it could send her to jail, so Kane has to keep her out of jail — which is how he ends up with a leggy blonde receptionist.

Meanwhile Vic Telli (Eduardo Ciannelli) is fresh out of jail, a haunted gunman sent up by the Doc’s testimony. Everyone assumes Vic wants Doc dead — but what he really wants is a favor. Vic is dying: “I’m up to my neck in my own grave …” and wants Doc to see his innocent daughter gets the $100,000 dollars he has put back for her legally.

How much trouble could that be?

Pat: Doc, will you tell me why you hang around Times Square getting mixed up with these broken down Cinderella’s, Broadway screwballs, stale actors … I’m afraid they’re gonna jam you up …

Doc: I don’t know Pat. Maybe it’s because they need me more.

But jammed up he is. Telli is murdered in his office (fried by a heat lamp) and Doc promptly knocked out and framed. Someone wants Telli’s hundred grand for themselves.

Pretty soon Doc is on the run from the cops and the crooks. And then his new receptionist gets kidnapped.

All they want is the money. But Doc is in a cell and his only hope is to run a con on the kidnapers and rely on his army off the Broadway streets — grifters, hoods, news vendors, and the like.

In the meantime Doc is, as crooked haberdasher J. Carroll Naish puts it, “… half way between the hot foot and the hot seat.”

And you just know Doc and the girl are going to end up back on a ledge over the streets of New York before it’s over.

This handsomely shot B-programmer was Anthony Mann’s debut film. It is mostly shot at night in the reflected shadow of flashing neon and with the constant chatter and blare of Times Square in the background. It is peopled with a colorful cast out of central casting by way of Damon Runyonville and moves at a rapid pace full of fast talking and faster thinking.

Dr. Broadway is based on a series of stories written by Borden Chase for the pulps and was the pilot for a possible series that didn’t develop sadly. Chase may be more familiar to you for his books that became films (sometimes with his screenplays) like Red River and Lone Star.

Macdonald Carey had a long career as a mid-level leading man, and was always reliable. He brings an earnest and easy going charm to the central character as Dr. Timothy Kane, and Jean Phillips is good as the slightly dizzy blonde receptionist/girl friend caught up in his world.

Richard Lane could play good but frustrated cops in his sleep (he was most often the brunt of Boston Blackie’s adventures), while Ciannelli had at least one really good scene as the haunted gunman (reminding us how seldom he was used as effectively as he might have been) and J. Carroll Naish has some fun as the crooked haberdasher behind it all. Gerald Mohr appears briefly as a hood not long before he would be the voice of Philip Marlowe on radio.

There is no real mystery here, mostly just a fast paced crime drama.

Familiar faces like Warren Hymer, Sid(ney) Melton, Olin Howard, Mary Gordon, and Jay Novello round out the cast as various Broadway types.

Now, before someone starts, this is a slick fast paced, exciting B-programmer, but despite the direction of Anthony Mann, it is not noir or even proto noir. There are a few touches that will eventually become noir, but they were nothing new to this kind of film in 1942, and good as it is, entertaining as it is, it’s not a precursor of film noir.

You only have to look at a film like I Wake Up Screaming to see the difference. It’s far above average, but in many ways, it could have been made at any time from the start of the talkies as a slick mix of crime, humor, and characters. At most its a cousin of noir-like Mann’s Two O’Clock Courage.

There is an almost indefinable quality that makes a film noir, and this one doesn’t have it, even though it touches on some of the themes and styles.

On a personal note, it took me over twenty years to catch up with this one, ever since I read about in William Everson’s The Detective In Film. Usually when you wait that long it is a disappointment — this one is not. It is everything advertised, and the copy I have from the collector’s market is only a little soft, but otherwise extremely good.

This is a superior B-programmer from a time when they were often the best thing on the bill. Heat up the popcorn and enjoy it. If you look real close you will even see some of the promise of Anthony Mann to come. But either way it is a rapidly paced sixty eight minutes making the most of its low budget and an army of New York types.

You will probably enjoy it far more than its modest origins might suggest.