DORNFORD YATES AND THE CLUBLAND HEROES

by David L. Vineyard

You should be warned before venturing into Dornford Yates country that there is no middle ground. Either you will be charmed and drawn in to the never-never land of his mostly between-the-wars adventure tales set in a Europe that owes more to Anthony Hope’s Ruritania or George Barr McCutcheon’s Graustark (Yates own Ruritania was the mythical Carinthia) than Eric Ambler’s back alleys, or you will throw up your hands in disgust. There’s little in the way of gray area when it comes to Yates.

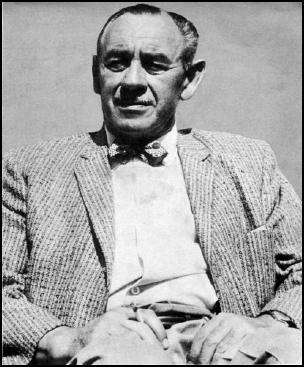

Yates was in reality Major Cecil William Mercer (1885-1960), a solicitor and the son of a solicitor (two of the three writers Richard Usborne calls the “Clubland” writers, Yates and Buchan, are solicitors, which may or may not mean something) and a cousin of H.H. Munro (Saki), seems to have been a bit of a crank and certainly thoroughly unpleasant.

Pawky, bossy, and quick to take offense, his reaction to World War II was largely to complain he had to leave his French home, and his reaction to Post-War England was so violent he picked up and moved to Rhodesia where he ensconced himself in a small personal fiefdom.

Neither A. J Smithers’ biography (Dornford Yates, A Biography) nor O. F. Snelling’s biographical sketch (“The Disagreeable Dornford Yates” at Wes Britton’s SpyWise blog) manage to project a very likable individual, and Richard Usborne, whose book The Clubland Heroes is the major study of Yates, Sapper, and John Buchan’s fiction, recounts how Yates threatened legal action when contacted because Usborne misused the term cad. Luckily it is the fiction and not the man under review here.

From the early twenties into the fifties, Yates wrote some of the most delightful books of his era. The Wodehousian books about Berry and Company are light-hearted romps featuring upper middle class Englishmen and women and their hijinks at home and abroad (smuggling of goods to avoid the duties was virtually a sport in Yates novels). The tone is light and playful, and the books retain much of their original charm.

The thrillers feature much the same European settings, and Jonah (Jonathan) Mansel ties the two types of books together, but while he’s still bossy in the Berry books, the Mansel of the thrillers is an altogether more dangerous character who once killed a man (the splendidly named Barabbus) with a single blow of his fist. (William Chandos, Mansel’s second in command and hero of his own books also does for a villain with a single blow, though in his case, Goat, is only a henchman, not a master criminal.)

The Mansel books and some non-series works usually team Mansel with William Richard Chandos, and George Hanbury, a pair of younger men who were sent down from Oxford after beating up some Bolshies (keep in mind this is written while the Russian Revolution was still making headlines).

In the first of the thrillers, Blind Corner, Chandos and Hanbury are on the Continent when they stumble on a murder, and the dying Englishman leads them home where a clue in the collar of the dead man’s dog eventually leads to Mansel, who has the ear of the Foreign Office, Scotland Yard, the Surete, and it is suggested MI6.

Soon they are up to their necks along with their servants Carson, Bell, and Rowley (no Yates hero would go abroad without a servant in company) in battle against Count Axel the Red, and before it’s over splitting a notable treasure among themselves and the servants.

This adventure takes them to Carinthia and Castle Wagensburg, where Mansel notes with some pleasure: “If you fought a duel with a pair of Lewis guns nobody’d take the trouble to come see what it was.” (Incidentally that odd apostrophe d for “nobody would” is a typical Yates touch. He sprinkles them everywhere.)

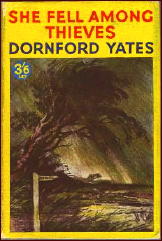

Names play a great role in the pleasures of Yates. Among the thrillers, titles like Cost Price, She Fell Among Thieves, Red Sky at Morning, Lower than Vermin, An Eye For a Tooth, Storm Music, and Perishable Goods promise what they deliver.

Then there are the villains (rotters to a man) like Count Axel, Rose Noble, Duke Saul of Varvic, Barabbus, Casca de Palk (“the English Willie with a mouth full of teeth and an Oxford accent”), Lord Withyham, Oliver Bleeding, Erny Balch, Daniel Gedge, Douglas Bladder, Boris Blurt, Coker Falk (an American), Sycamore Tight, and Major Von Blodgenbruck among the rogues’ gallery, with helpers whose names are things like Jute Shade (a crooked private detective), Goat, Lousy, and Sweaty.

Yates is also a great one for fine place names like the Castles of Gath, Midian, and Jezeel, and estates like White Ladies, Gracidieu, Break o’ Day, Poke Abbas, and Mockery Hall. There’s even a village named Broad i’ the Beam.

Dickens’s lower middle class sentimentality probably didn’t sit well with Yates, but his character names most certainly did. He has a less than kind view of his own profession as well, with solicitors like Biretta and Cain, Aaron and Stench, and Oxen and Baal not uncommon. (It’s a wonder they ever got a client.)

Whole volumes could be written about Yates use of the English language, but it suits the novels well. Berry, warned he will get his hands dirty during a bit of second story work replies:

“That were impossible … If I massaged a goat in a coal-mine, I couldn’t get these hands dirty.”

or this from Mansel in Perishable Goods:

“But for the whistle I heard, that it was not you, Chandos, would never have entered my mind.”

and:

“Rose Noble may have a fine hand, but he knows us too well to sleep sound when we are out of his ken.”

and something must be said of Jonah’ highhandedness as in The House That Berry Built, when he has done for the wretch Stapely:

“An unknown man is found dead, We can do for the details later, don’t you agree, Falcon? (Superintendent Falcon of the Yard)”

Philo Vance or Sherlock Holmes could hardly have done it better. Falcon, naturally, agrees. Only villains ever balk at Jonah’s commands, and they usually end badly.

Where women play little role in the novels of Sapper or Buchan, they are important in Yates world. Phyllis Drummond largely exists to be kidnapped in Sapper’s (H.C. McNeile) Bulldog Drummond books and Irma Peterson mostly to do the kidnapping and seek revenge for the death of her beloved Carl.

Buchan’s women tended to be practical and boyish, but not particularly attractive, though Janet Roylance in John McNab and Kore Arabin in The Dancing Floor have their moments.

This isn’t to suggest Yates is a proto-feminist, but the ladies who occupy his books are smart and attractive and well worth the risks involved rescuing them. There’s even a hint of sex that raises its head in Yates such as when Mansel has John Bagot and Audrey Nuenham registered as man and wife in French hotels while on the run after Bagot has already had to strip her unconscious form and rub her down after a near drowning.

Or take Storm Music where the hero and heroine take refuge in an idyllic woodland cabin, take time out for a skinny dip in a remote forest glade, and spend the night together during a magnificent thunderstorm. Nothing is ever stated, but there is a good deal implied, or inferred by the reader. And the ladies often set their sights for Chandos or Mansel, though in Mansel’s case to no use.

And there is no shortage of deadly traps in the books. Castle walls must be laid siege to, and some very nasty dungeons escaped. In Red Sky at Morning a remote schloss has a treacherous Judas floor that very nearly does our heroes in (a Judas floor is one built on a pivot that when released can drop you into a nasty inescapable dungeon underneath) and the threat of ending in some cold moat or down a Jacob’s ladder ala The Prisoner of Zenda is always present.

Barzun and Taylor praised Yates for his use of “Sturm und Drang” in A Catalogue of Crime, and it’s an apt phrase, for weather and scenery and setting play a large role in the charms of the books. Storms roll across the tops of mountains, fogs hamper deadly races along treacherous roads, and natural wonders like waterfalls are always good for dispatching villains or first glimpsing a beautiful damsel. Yates took the term “blood and thunder” literally and never skimps on either. It’s almost impossible to write about Yates and not use the term full-blooded.

Like most of the heroes of the era Mansel and company are a law unto themselves, and seldom waste time with the authorities, save for a bit of cleanup at the end. They have a particular disregard for customs authorities, and Mansel’s Rolls and Aston Martin both have secret compartments used to smuggle treasure, brandy, and his sealyingham terrier, Tester past nosy customs men. (It’s been suggested that Mansel’s Aston Martin inspired James Bond’s in Goldfinger.)

The books are adventure, thrillers, not detective stories, though Yates did write one detective novel, Ne’er-Do-Well (1954) in which Superintendent Falcon relates a case to Chandos and Mansel, but Yates proves no threat to Agatha Christie. Clever puzzlers were not his forte. But most of the books, humorous and serious have criminous ties, and all are informed with an almost addictive sense of adventure as a form of play (as opposed to duty in Buchan).

Readers interested in Yates will find A.J. Smithers book Dornford Yates, A Biography and Richard Usborne’s The Clubland Heroes invaluable. Usborne’s book is perhaps the only one to really study the phenomena of Yates, Sapper, and Buchan’s ‘shockers’ and is a classic in the field. Luckily it has been reprinted often enough that it isn’t hard to find or particularly expensive when found. I have relied on it heavily in writing this since my Yates books are currently still boxed up.

For those wanting to dip their toes in, but not invest any money, several of the Berry books are available as free ebooks at Project Gutenberg and Manybooks to be read online or downloaded.

One of the short stories from Brother of Daphne was adapted as an episode of the BBC series Hannay about John Buchan’s hero Richard Hannay, and the first episode of Mystery! shown in this country was She Fell Among Thieves, with Malcolm McDowell as Chandos and Michael Jayston (Nicholas and Alexandria and Quiller) as Mansel.

There is also a musical with lyrics by Yates. Sadly the books were never adapted to film in their day, which is a shame, since they are cinematic and romantic, and the Berry books would make a wonderful television series, all done with a light touch.

Yates isn’t going to be for every taste, but if you like a bit of adventure, the romance of low-slung cars on treacherous roads at high speeds, dastardly villains, clever heroes, and worthy heroines Yates is your man. True, the term Snobbery with Violence could have been coined to describe Yates novels, but if you are very sensitive to class consciousness you probably won’t be reading much between the wars fiction anyway.

Yates is the kind of writer designed for a stormy night and a roaring fire with a cat snoring in your lap and or a good dog at your feet, even if you are really reading in bed with the television on for background noise. Reading Yates is the next best thing to a pipe and smoking jacket, and a good deal more comfortable and healthy.

But I warn you. His particular brand of the whole Clubland scene can be addictive.