Search Results for 'Dorothy L. Sayers'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Wed 9 Sep 2009

Posted by Steve under

ReviewsNo Comments

THE THING IN THE NYMPH,

by David L. Vineyard

“The Wizard’s Belt” by T. P. HANSHEW, from Cleek, the Master Detective. Doubleday, US, hardcover, 1918. Originally published in the UK as The Man of the Forty Faces (Cassell, hc, 1910).

In relation to Hanshew and Cleek I’ve previously mentioned [Comment #2] a story that I thought might have inspired one of Dorothy L. Sayers more bizarre and memorable Lord Peter Wimsey short stories: “The Abominable History of the Man with Copper Fingers” in Lord Peter Views the Body. “The Wizard’s Belt,” the sixth story in the twelve story collection Cleek, the Master Detective is that story.

As was common in that era, the book is what science fiction fans used to call a ‘fix-up,’ meaning related short stories that more or less form a novel narrative. This one features Hamilton Cleek, formerly the “Vanishing Cracksman,” and the one time king of Maurivania (he still lives of in fear of assassins and the agents of the French criminal underground known as the Apaches), a master of disguise (the Man of Forty Faces — apparently he was no Lon Chaney), and now a consulting detective for Scotland Yard, and his friend Mr. Maverick Narkom.

Since there is no possible way to discuss this story without giving away major elements, here is a

As the story opens, Narkom has contacted Cleek about a curious mystery that has arisen and the plight of a young woman and her invalid father, a couple of modest means. It seems her beau has disappeared from his room at their house with no trace. During an evening’s entertainment attended by the young lady, Miss Mary Morrison and her father Captain Morrison, the fiance George Carboys, and an artist friend Van Nant, Carboys began to talk about his days in the far east and the fortune owed Carboys by a wealthy Easterner who never gave him anything but some worthless trinkets — among them a blue leather belt claimed to have the power of invisibility.

Carboys then donned the belt, and still wearing it went to bed. The next morning he was not to be found. The belt lay on the floor in the locked room, and Carboys has vanished without a trace.

“Necromancy — wizardry — fairy lore — all the stuff and nonsense that goes into the making of ‘The Arabian Nights’ … All your ‘Red Crawls’ and your ‘Sacred Sons’ and your ‘Nine-fingered skeletons’ are fools to it for wonder and mystery. Talk about witchcraft! Talk about wizards, and giants, and enchanters and the things that the witches did in MacBeth! God bless my soul they’re nothing to it …”

Obviously Narkom is impressed. Cleek less so, to give him credit. But he takes the case and goes to investigate under the guise of George Headland. Once at the Morrisons he learns Carboys had an important meeting with a solicitor the next morning, and examines the man’s room.

In rather good minor Holmes style he quickly dismisses the obvious. “Our wonderful wizard does not seem to have mastered the simple matter of making a man vanish out of the thing, without first unbuckling the belt,” Cleek opines, and then goes on to point out that the belt is English and American, not from the Middle East, that Carboys had shaved, but not undressed, and obviously went out again unseen.

Still he has vanished. The sharp eyed Cleek also see Miss Morrison keeps pigeons, and notes some strange about one of the birds.

His investigation then takes him to Van Nant’s studio where he discovers among other things a statue of a Roman Senator, and a large rather ugly and misshapen figure of a nymph recently carved, and showing no signs of Van Nant’s talents. “My touch seems to have deserted me. Temporarily I hope.”

At this point Cleek announces he is baffled and can only hope to consult a clairvoyant. He arranges for Narkom to have the Morrisons and Van Nant meet at the Morrison’s house the next night, where no one less than the famous Hamilton Cleek will show up to solve the case.

But when Cleek doesn’t show, Narkom tells the others that Cleek is going to visit Van Nant’s studio before coming to the Morrison home. Van Nant feels he should be at home to meet Cleek, even though Cleek wouldn’t need to key to get in, and leaves. He arrives at his studio, calls out for Cleek though there is no answer, and goes directly to the ugly half-formed figure of the nymph.

At which point the statue of the Roman Senator pounces on him, wrestles him to the ground, and snaps on the cuffs. As Cleek, disguised as the statue, announces his arrest Narkom and the police burst in. They take the prisoner, and Cleek takes a hammer to the statue of the nymph — revealing the body of George Carboys inside.

It seems Carboys’ old friend the Eastern potentate had died and left a considerable fortune to Carboys. Van Nant knew, and since there was an old will naming him Carboys heir, that would be invalid when Carboys married Miss Morrison, he lured Carboys to his studio by making him think Miss Morrison was his secret lover, murdered him, and encased the body in the modeling clay.

He might have gotten away with it too if Cleek hadn’t seen a speck of clay on one Miss Morrison’s pigeons, the one Van Nant used to plant the note luring Carboys to his studio to be murdered… The note, allegedly from Miss Morrison, is found in Carboy’s pocket.

Hanshew must have liked the idea because he used it before in one of the stories in Cleek of Scotland Yard (1914) in a story involving another locked room — this one made of glass — a missing boy, and a waxworks. Of course it was also the plot of the film Murder in the Wax Museum and its remake, House of Wax. I seem to recall it even happened in reality once, but that may be an urban myth like poodles and microwave ovens.

You can see why John Dickson Carr was a fan of Cleek other than Hanshew being another American expatriate living and writing in England. For sheer melodrama and weird crime Cleek can be hard to beat. Quite a few locked rooms and impossible crimes occur, though they might be less mysterious if Maverick Narkom wasn’t prone to exaggeration, melodramatic statements, and hyperbole.

But then what can you expect from someone who thinks it is the height of discretion to pick the mysterious and secretive Cleek up in a red limousine.

Some of the stories are more preposterous than this, but almost all are fun, and Cleek has some of the true Holmes style as well as some of the traits of later pulp heroes like The Shadow or Phantom Detective. True, most of his big revelations are pretty obvious, and Holmes could have solved them with half a cigarette — no three pipe problems here — and some do fall into the category of Raymond Chandler’s famous critique of Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express — only a moron could have solved it.

Hanshew mostly walks a fine line between genuine mystery stories and pure claptrap, but he does walk it, and even when he misses a step the result is interesting. The writing does suffer a bit from some of the flaws of the era — a touch of what American writer and critic John Gardner called the Pollyanna school of writing, but for the most part Hanshew and Cleek are entertaining — even when laying it on a bit thick.

Of course there is no evidence Dorothy L. Sayers read this story or borrowed from it, but there are certain similarities. Her own story is better and builds to a nice chill at the end, but the Hanshew tale has its charms, and is accompanied by a nice illustration by Gordon Grant.

And whether the story inspired Sayers or not, it is one of the better Cleek tales, pardoning the melodrama and high handedness. Overall a good tale in a fairly good collection of one of the more interesting writers and creations of the period.

Still, I’ve always wondered why only forty faces? Maybe that was Hanshew-the-actor’s own limits. Surely he must have imagined himself playing his creation on stage. Even Conan Doyle never got to be Sherlock Holmes in the theater. Maybe forty faces was all he thought he could handle.

Editorial Comment: Besides David’s previous comments about Thomas Hanshew on this blog (follow the link in the first paragraph above), Mike Grost reviewed Cleek, Master Detective in its entirety in this followup post.

Sat 23 May 2009

Introduction: The following is an email that David Vineyard sent me following my request for a photo of mystery writer Philip MacDonald. A photo’s since been

found, but I thought the rest of David’s comments were worth sharing.

— Steve

I know a lot of classical detective fans don’t care for MacDonald because he tends toward suspense and even melodrama, but I’ve always thought his best books a sort of antidote to the driest and most formal of the golden age.

I love a good puzzler, but some of the practitioners sometimes forgot that one of the essential parts of the definition of mystery involves some sort of emotional response, not merely intellectual stimulation. Only Freeman ever managed to be dull and interesting, and Dr. Thorndyke is a hard act to follow and most got the dull part right, but not the interesting part.

Thorndyke is unique among fictional detectives in that he came first, and then the real life model, Sir Bernard Spilsbury. Most people don’t realise how much impact Thorndyke had on actual forensic investigation. I don’t know if it still is that way, but the box the forensic kit used to be carried in was always green after Thorndyke’s green forensics kit.

Much of the actual procedure of evidence collection used by the Yard and then by police around the world was taken from Freeman’s descriptions, and the actual forensics box based on his.

I ran across a terrific article in a 1914 issue of the New York Times on their archive site. Seems when Thomas Hanshew, author of the “Cleek, Man of Forty Faces” books (John Dickson Carr was a huge fan), was suspected to have been Bertha M. Clay when he died.

Hanshew, an actor who was one of Ellen Terry’s stock company, and died in England where he was living (and where the Cleek books are set), was a hugely prolific writer who wrote some 150 novels.

Clay, who was Charlotte M. Brame, was a popular writer of books for women (notably young women) whose work was issued in paperbound editions similar to the Nick Carter Nickel Library.

When she died in 1884 Street and Smith were unwilling to give up the golden goose, and apparently Hanshew, John Corryell (Nick Carter), and others took over, sometime writing from her notes, other times probably writing their own books.

The article is particularly kind to both Hanshew and Clay, and not the least snobbish (well, a little when it refers to her young female readers with mint on their breath — waiting in vain, we assume, for that first kiss), and even gives a few examples of how Hanshew changed Clay’s originals to his own style.

The article comes complete with a very nice drawing of Hanshew, who was a handsome fellow. If you have never read the Hanshew books, many of them can be downloaded from Google Books On-Line library, and while they are full of melodrama and over the top writing, you will begin to see what Carr liked about them. I freely admit I sometimes get my fill of the literary and want something bad but fun. Hanshew made the cut in Bill Pronzini’s Gun in Cheek books, and deserves it. He is a true alternative classic.

Hanshew doesn’t play fair as a detective novelist, but Cleek is an interesting character. The heir of a royal throne, he is the finest cracksman in London (The Vanishing Cracksman), but as usual true love turns his hand and he reforms, being hired by Maverick Narkom (great name) Superintendent of Scotland Yard as a consulting detective.

High handed and theatrical (as you might expect from an actor) the books are bad writing at its best. One of the stories seems to me may have been the source for one of Dorothy Sayers Wimsey shorts, the one where Lord Peter finds the sculptor is hiding real bodies in his bronzes.

Impossible crimes and locked rooms are common stuff, but the solutions are often of the poison unknown to science type. The Google edition available of Cleek of Scotland Yard includes the photos from either a silent film or play (I’m not sure which).

Little as either Clay or Hanshew is known now, it seem strange that they should have merited a New York Times article in 1914. Anyway, sometime you might treat yourself to a taste of Cleek, his true love Alicia, his servant Dollops, Mr. Maverick Narkom, and Margot, Queen of the Apaches (French Apaches, not American ones). Readers once read this breathlessly, and truth be told even today they can take your breath away, though not perhaps as they intended to.

Sun 19 Apr 2009

Posted by Steve under

Authors ,

Reviews1 Comment

A Review by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

E. C. BENTLEY – Elephant’s Work: An Enigma. Hodder & Stoughton, UK, hardcover, 1950. Alfred A. Knopf, US, hardcover. 1950. Also published as The Chill. Dell 704, paperback, 1953.

E(dmund) C(lerihew) Bentley is one of the magical names in the mystery genre. His book Trent’s Last Case (1912) is usually cited as the birth of the Golden Age of the British detective novel, and certainly the book that carried the genre from the short form practiced by Doyle, Chesterton, and Morrison, to the novels championed by Christie, Sayers, Berkley and others.

In addition to the classic Trent’s Last Case Bentley also wrote a collection of short stories featuring journalist and amateur sleuth Philip Trent, Trent Intervenes (1938), and a second novel, Trent’s Own Case (1936) with H. Warner Allen, but then was silent in the field until 1950 when he penned Elephant’s Work: An Enigma.

And enigma is exactly what Elephant’s Work is. Bentley dedicated the work to John Buchan, and it is certainly in the form of a “shocker,” inspired when Bentley expressed his admiration for Buchan’s The Thirty Nine Steps and Buchan suggested Bentley pen his own. The result forty years later was this book. In retrospect he should have ignored the advice and stuck to detective stories.

The novel begins promisingly. The hero Severn boards a train where he encounters a formidable American and learns there is a dangerous fugitive abroad. As they wait, there is a ruckus coming from a nearby circus train. An elephant has escaped and gone on a rampage. When the elephant goes wild again on the train and causes a wreck, Severn is knocked unconscious.

When he awakens, he is suffering from amnesia and finds he is the guest of one General da Costa who informs him the name on his passport is Taylor, and while the General, the doctor, and everyone else are all perfectly kind, it soon dawns on Severn he is a virtual prisoner, and his fate is involved with someone known as Nick the Chill who works for a gangster called Farewell Billy.

In fact it is more than implied by the General and others that Severn is none other than Nick the Chill, a gunman in the employ of Farewell Billy.

So far so good. The writing is clean and clear and the suspense well calculated. The sense of mystery and Severn/Taylor’s confusion and growing paranoia well drawn. Is he the deadly Chill, or an innocent man being set up to take the fall in some elaborate scheme? Buchan himself could hardly have done it better, especially when Severn/Taylor eludes his protectors and tries to piece the mystery together pursued by mysterious sinister men and unable to go to the police who may believe he is a dangerous killer.

And then Elephant’s Work takes the most absurd twist you can imagine. I almost hesitate to reveal it, save unwary readers might think Elephant’s Work was a lost classic of the thriller genre only to run aground on the most unlikely reef in the history of the chase and pursuit novel.

Severn isn’t Taylor, and he isn’t Nick the Chill, he’s the Bishop of Glanister, on a little holiday before taking up his new duties — as the just appointed Archbishop of Canterbury — and the entire conspiracy has been the hastily contrived work of his friends attempting to protect him from any potential bad publicity while he was recovering his memory.

If at this point you feel the need to throw the book across the room, it is at least a small volume. Of course there is a bit more to it than that. The General himself was a fugitive of sorts who didn’t want Severn’s presence to reveal where he was until his situation was settled, but even that is hardly a satisfying explanation why everyone behaves in the most absurd manner possible and for the most absurd of reasons.

Ultimately Elephant’s Work is one of those annoying books where if anyone behaved halfway reasonably or made some effort to actually think, the entire facade would come crashing down like the house of cards the author has constructed. You should on general principle avoid any book which the author subtitles an “Enigma.” Chances are he means it.

This shouldn’t put anyone off reading Bentley’s classic detective novels. While it’s a bit dated, Trent’s Last Case is a genuine classic, and both Trent Intervenes and Trent’s Own Case are exceptional works in the genre.

Philip Trent is the model for many of the amateur sleuths to come later and especially an early influence on Dorothy L. Sayers and Lord Peter Wimsey. Bentley was a clever and charming man who gave his own name to the playful four line stanzas known as Clerihews he wrote in school and which were published with illustrations by G.K. Chesterton as Biography For Beginners. Bentley himself was a respected journalist and editorial writer for the Daily Telegraph.

But be forewarned, Elephant’s Work is one of the single most annoying thrillers ever written, light as a souffle only because it really is filled with hot air. And be careful where you throw it. You might upset an elephant and start the whole absurd business all over again.

The victim of Trent’s Last Case is the millionaire Sigsbe Manderson, that name being a motive for murder if nothing else, as some wag once pointed out. Trent’s Last Case was filmed twice, the second time as The Woman in Black with Michael Wilding as Trent and Orson Welles as Manderson.

Despite, or because of that, it’s a dull affair all around. Luckily we were spared the film version of Elephant’s Work — one of those small mercies we should be grateful for.

Sun 20 Nov 2022

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

JOHN DICKSON CARR – The Crooked Hinge. Dr. Gideon Fell #8. Harper & Brothers, hardcover, 1938. Popular Library #19, paperback, 1944. Reprinted many times.

SHADOWS WERE GATHERING ON the lower slopes of the wood called Hanging Chart, but the flat lands to the left of it were still clear and warm. Set back from the road behind a wall and a screen of trees, the house had those colors of dark-red brick which seem to come from an old painting. It was as smoothed, as arranged, as its own clipped lawns. The windows were tall and narrow, with panes set into a pattern of stone oblongs; and a straight gravel drive led up to the door. Its chimneys stood up thin and close-set against the last light.

No ivy had been allowed to grow against its face. But there was a line of beech-trees set close against the house at the rear. Here a newer wing had been built out from the center—like the body of an inverted letter T—and it divided the Dutch garden into two gardens. On one side of the house the garden was overlooked by the back windows of the library; on the other by the windows of the room in which Sir John Farnleigh and Molly Farnleigh were waiting now.

A clock ticked in this room. It was what might have been called in the eighteenth century a Music Room or Ladies’ Withdrawing Room, and it seemed to indicate the place of the house in this world. A pianoforte stood here, of that wood which in old age seems to resemble polished tortoise-shell. There was silver of age and grace, and a view of the Hanging Chart from its north windows; Molly Farnleigh used it as a sitting-room. It was very warm and quiet here, except for the ticking of the clock.

What the Farnleighs are waiting for, though they don’t yet know it, is foul murder, a hint of the supernatural, Satanic cults, possible robot killers (in 1938), and a killer whose lack of genius almost overwhelms the brilliance and eccentricity of Dr. Gideon Fell’s efforts to unravel the mystery.

But pause a moment to admire the literary skill in this little scene at the start of Chapter Two of The Crooked Hinge, a classic Carr mystery. It not only established Farnleigh Close, which is both the setting and the McGuffin that seemingly sets the action in motion but it sets a mood. Chimney’s are “thin and close,†the woods are called Hanging Chart and shadowed ominously, the “silver of age and grace†lays over a room. A clock ticks at the beginning of the paragraph and is brought in again at the end, establishing a tension. Something is coming. Something sinister though nothing concrete has been said to tell us that.

Carr does this effortlessly, his use of metaphor and simile as sharp as Chandler, though applied to a different end.

Even the title, The Crooked Hinge, suggests something sinister about a house, something not quite right about it or the people in it.

The setting is Kent, where John Farnleigh (“The old-time Farnleighs were an unpleasant lot…â€), a survivor of the Titanic lives with his wife in Farnleigh Close, but another claimant has shown up claiming to be the real John Farnleigh and an inquest is scheduled to establish the truth. Carr tries out his own solution to the famous Tichborne Claimant case.

Then the first Farnleigh is murdered by the pool, his throat slashed in front of three witnesses, and none of them saw anyone do it and the police can’t find the weapon.

Is it the automaton modeled on Maezel’s Chess Player that reaches out to touch a maid and nearly frightens her to death, and who stole the thumbograph, a device for taking fingerprints, not to mention the suggestion of a cult of Satanists. DCI Elliot (…â€youngish, raw-boned, sandy-haired, and serious-minded. He liked argument, and he liked subtleties…â€) investigates and calls on Dr. Fell to sort out the sinister goings on, as he points out:

“But, even believing that this is murder, I still want to know what our problem is.â€

“Our problem is who killed Sir John Farnleigh.â€

“Quite. You still don’t perceive the double-alley of hell into which that leads us. I am worried about this case, because all rules have been violated. All rules have been violated because the wrong man had been chosen for a victim…â€

A ranking of the top ten impossible crime mysteries of all time placed this one number four. It is Fell and Carr at their considerable best. It is dedicated to Dorothy L. Sayers.

Just why the wrong man was murdered becomes as important as how. Fell cannot quite lay hands on why the murderer struck and why he has not struck again: “This murder is human, my lad. I’m not, you understand, praising the murderer for this sporting restraint and good manners in refraining from killing people. But, my God, Elliot, the people who have gone in danger from the first! Betty Harbottle might have been killed. A certain lady we know of might have been killed. For a certain man’s safety I’ve had apprehensions from the start. And not one of ’em has been touched. Is it vanity? Or what?â€

In finding the solution Fell even calls on S. S. Van Dine and Philo Vance’s favorite work, Criminal Investigations: a Practical Textbook by Hans Gross (The Bishop Murder Case) to explain the esoteric but quite real murder weapon (and true to Carr he has laid the groundwork for the killer’s expertise with the weapon) and in a real twist reveal the killer twice in a single chapter.

The Crooked Hinge is Carr and Fell at their best. The mystery sparkles with hints of something unhealthy and outside the realm of the possible, with Fell at his eccentric, high handed, and deceptive finest, and full of well-realized characters just the right side of cardboard, neither overwhelming the story nor mere cut-outs to be moved on the board.

This is a model for the genre, especially that special corner of impossible crime and hints of something sinister and beyond that John Dickson Carr made his own.

Thu 3 Nov 2022

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

JILL PATON WALSH – The Wyndham Case. Imogen Quy #1. Hodder & Stoughton, UK, hardcover, 1993; trade paperback, 2003. St. Martin’s, US, hardcover, 1993.

Jill Paton Walsh, who died in 2020, was first best known as the author of a long list of children’s book. She rose to fame in “our†field for being chosen to complete one of Dorothy L. Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey novels, left unfinished at the time of her death (Thrones, Dominations, 1998), followed by three more Wimsey novels written on her own.

Alongside these she wrote the four books in her Imogen Quy series, of which this is the first. Imogen is a young nurse at St. Agatha’s College, Cambridge University — an interesting way to write detective mysteries involving college professors and deans in action, up close and personal, but yet from the outside, without having a major stake in the game.

The “Wyndham Case†is actually (as a play on words) the spectacular shelving unit in a special, separately endowed scholarly library at St. Agatha’s, complete with arcane requirements for its care and financial upkeep . Found dead there one morning is a student who, because of his meager means, is suspected by many of being there for nefarious reasons. Thievery,

A close male friend of Imogen is a police officer, which is always a good way to get a layperson involved in a murder case. Imogen is, in fact, invited by him to do just that when the students in the dead boy’s life stonewall the police.

Walsh has to have been a good choice to continue to Peter Wimsey series. Her prose is clear, precise, witty, and just fusty enough to qualify. (I haven’t read any of them.) Imogen Quy (rhymes with “whyâ€) is quiet but both perky and intelligent enough to be able spend a lot of enjoyable time with – perhaps too much so, as the fully absorbed reader (me) can easily find him- or herself so caught up in her personal life as to let the clues in the case slip on by Me again).

Do not lose yourself in the game, therefore, and miss sight of the goal. Read and remember all the details as the case goes on. They will all be there (mostly).

I enjoyed this one.

The Imogen Quy series —

The Wyndham Case (1993)

A Piece of Justice (1995)

Debts of Dishonour (2006)

The Bad Quarto (2007)

Fri 30 Sep 2022

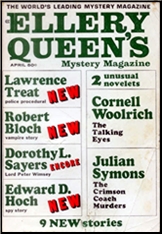

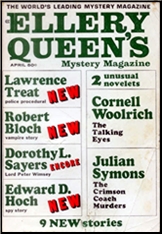

ELLERY QUEEN’S MYSTERY MAGAZINE April 1967. Overall rating: ***

JULIAN SYMONS “The Crimson Coach Murders.†Novelette. First published in The Evening Standard, 1960, as “The Summer Holiday Murders.” A detective story writer seeking background material takes a tour through southern England. Murder gives him a chance to try his abilities. (3)

ROBERT BLOCH “The Living Dead.†A World War II vampire story; not too imaginative. (2)

EDWARD D. HOCH “The Spy Who Came Out of the Night.†Rand of Double-C is sent to Berne to decode a message. His bitterness is forced to light. (3)

JACQUELINE CUTLIP “The Trouble of Murder.†A murderer burns down his inheritance unknowingly. Dry and confusing writing, but ending is good. (4)

CORNELL WOOLRICH “The Talking Eyes.†Novelette. First published in Dime Detective Magazine, September 1939, as “The Case of the Talking Eyes.†A paralyzed woman, able to communicate only wth her eyes, overhears her son’s wife plotting to kill him. Unable to stop the murder, she manages to avenge his death. Who else could attempt such a story? (4)

RHODA LYS STOREY “Sir Ordwey Views the Body.†Anagram-pastiche [by Norma Schier] of [Dorothy L. Sayers’] Lord Peter Wimsey. (1)

DOROTHY L. SAYERS “The Queen’s Square.†First appeared in The Radio Times, December 23, 1932. Lord Peter Wimsey solves a murder no one could have committed. A red costume in red light would appear white. (3)

JIM THOMPSON “Exactly What Happened.†Man disguised as another is killed by the other disguised as him. (1)

H. R. WAKEFIELD “The Voice of the Inner Ear.†First appeared in The Clock Strikes Twelve by H. Russell Wakefield, Herbert Jenkins, 1940, as “I Recognised the Voice.†A “psychic†detective solves mysteries. (2)

L. J. BEESTON “Melodramatic Interlude.†Revenge is thwarted by the victim’s wife. Obvious but still exciting. (3)

CHRISTOPHER ANVIL “ The Problem Solver and the Burned Letter.†Richard Verner reads a clue from a typewriter ribbon. (2)

LAWRENCE TREAT “P As in Payoff.†Mitch Taylor of Homicide Squad solves a hotel robbery as he tries to gain a favor. (3)

–January 1968

Sat 30 Jul 2022

Posted by Steve under

Reviews1 Comment

REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

J. JEFFERSON FARJEON – Seven Dead. Inspector Kendall #3. Collins, UK, hardcover, 1939. Bobbs-Merrill, US, hardcover, 1939. Poisoned Pen Press / British Library Crime Classics, US, trade paperback, 2018.

When journalist and yachtsman Thomas Hazeldean who has come ashore to post a letter spots Ted Lyte fleeing from a house on a remote part of the coast he and a constable catch him with silverware in his pockets, but Lyte is uncommunicative.

Something has scared the wits out of him.

They take him to police headquarters where Detective Inspector Kendall is on duty. A few inquiries prove that Haven House where the Fenners live has been mysteriously quiet for some time and no calls have gone through though several have been made. Kendall resolves to find out why and with two constables, a police doctor, and Hazeldean in tow goes to investigate.

Here there is a nice bit of a jump scare involving the “howler,†an intrusive device the phone service has to notify customers a call is being made to them.

What they find is six men and a woman in man’s clothes (“She might have been attractive once. She was not now.â€), all roughly dressed, all obviously worse for wear, and all dead.

The doctor can’t say from what, though they have been dead too long to have been Ted Lyte’s work. Mysteries abound, including a painting of a young girl with a bullet hole in it, a gun fired one time, a dirty cricket bat on the mantle where a clock had stood, a dead cat outside, rubber tubing, a mysterious underground work shop that smells strange, and a note with an odd address that says the Suicide Club on the other side.

Hazeldean makes for an attractive and believable co-sleuth who actually contributes to Kendall’s job as the two, apart and together, pursue answers to what happened. Why would seven strangers come to an empty house, the owners are away, and kill themselves, if it was suicide? Who are they, how did they come, and what is the meaning of their dirty worn clothing, the men are dressed like sailors, and emaciated looks. What ordeal did they face before killing themselves or being murdered?

Joseph Jefferson Farjeon, who also wrote as Anthony Swift, was a popular writer from a distinguished family who penned several books with Kendall as sleuth and even more about Ben the Tramp, a charming hobo who sometimes assists Scotland Yard. His books were admired by Dorothy L. Sayers, and it isn’t hard to see why. His characters are and smart and attractive, his plots move swiftly, his murders are less contrived and more natural than they first seem, his criminals kill for believable motives, and even when he throws in a romance (as he does here) it is between attractive and likable people the readers cares about.

In an era where bright young things could be an absolute pain to deal with in an otherwise good mystery novel Farjeon manages to keep them attractive and this side of believable. Hazeldean becomes fascinated by the girl whose picture has a bullet hole (who proves to be Dora Fenner, the now grown daughter of the owner, shades of Laura) in it, and follows a clue across the Channel to Boulogne where more mystery awaits.

Seven Dead gives us a classic Golden Age puzzle, good dialogue and by play between Hazeldean and Kendall, the latter smart without being unlikely (as Hazeldean says, “…he didn’t play the violin or have a wooden leg or something…,†and only a shade acerbic in an attractive way, and more importantly a reasonable solution that ends in a nice bit of melodrama that nevertheless develops from the plot and characters and doesn’t strain credibility.

It doesn’t hurt that Farjeon isn’t afraid to throw in thriller and adventure elements and blend them with the puzzle (he wrote several good chase novels too, including one filmed by Alfred Hitchcock, Number 17), meaning his books often seem less dated and formal than many of the greater lights of the genre. I suppose for some that is a drawback, but for this reader it is a definite plus.

The British Library Crime Classics version of this has a fine introduction by Martin Edwards and an attractive cover and is available reasonably. All the Ben the Tramp books are available currently and several of Farjeon’s others, and all the ones I’ve read have been entertaining, though not necessarily classics.

He’s not another Christie or Sayers, but he is great fun to read which isn’t always true of writers from his era. His books are old fashioned enough to fill that bill while written in a straight forward modern enough style not to leave the reader gritting his teeth, for a solid fast entertaining mystery novel of the era you could do a lot worse than Farjeon.

Tue 31 May 2022

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

It began, I suppose, with Lord Peter Wimsey. Early in the Golden Age of English detective fiction between the World Wars, Dorothy L. Sayers’ first Wimsey novels created the sub-branch of the genre whose hallmarks were donnish wit, literary allusions and a contemporary sensibility. Near the end of the period in which this type of whodunit flourished, the mantle passed from women authors like Sayers to men, notably Nicholas Blake, Michael Innes and, a few years later, in the middle of World War II, Edmund Crispin.

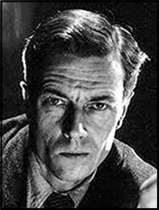

All three names were pseudonyms, the mystery-writing bylines of gentlemen with other careers. Blake, the one we are following today, was equally well known as C. (for Cecil) Day-Lewis (1904-1972), who along with his friends W.H. Auden and Stephen Spender was ranked among the foremost young poets of the post-WWI generation. Lovers of that form of literature remember him as England’s Poet Laureate from 1968 until his death, and for movie buffs he’s perhaps best known as the father of actor Daniel Day-Lewis.

I can’t remember when I began reading Nicholas Blake novels or even whether it was before or after we read the Day-Lewis translation of the Aeneid in high school. In any event it was generations ago. Recently I decided to revisit Blake and see how his work stands up today.

***

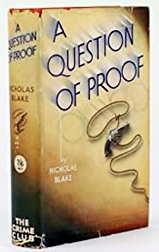

His debut novel, A QUESTION OF PROOF (1935), opens at Sudeley Hall, a preparatory school of the sort in which Day-Lewis spent several years as an instructor. Of the eighty-odd boys that it houses, the richest and most despised is Algernon Wyvern-Wemyss. His classmates refer to him as a squit and a worm, and if THE WIND IN THE WILLOWS hadn’t taught Brits to love the sweetly singing little amphibian known to biologists as Bufo bufo, no doubt they would have called him a toad.

On the end-of-term day when the inmates’ parents are invited to the school for fun and games, this young fiend is found strangled to death inside a hollow haystack which a few hours earlier had been the scene of a passionate rendezvous between one of the school’s instructors and the lovely young wife of its pedantic and tyrannical headmaster, who is also the dead boy’s uncle and only living relative.

Could the lovers have been caught in the act by the kid, and could one or both of them have strangled him to keep his mouth shut? There are of course more than two suspects, including some other instructors and the headmaster, who inherits most of his swinish nephew’s money. (With his complete lack of interest in law, Blake does nothing to explain how this came about.)

But the young man who visited the haystack is so deeply under suspicion that he sends to London for his old Oxford friend Nigel Strangeways, a Holmes-like consulting detective.

At first Nigel comes across as something of a silly-ass character, demanding endless cups of tea, singing an aria from Handel’s ISRAEL IN EGYPT during a wild auto chase (the first of many physical action scenes in Blake novels), submitting to a schoolboy secret society’s initiation rite that involves, among other things, putting a chalk mustache on the statue of a “nimph†in the village square.

But most of the time he plays his detective role well, preferring psychological to physical clues (of which there are none), recognizing that one unanswered question—why was the dead boy not seen by anyone in the hour or so before his death?—is the key to his murder.

When a second murder takes place, a stabbing with an improvised stiletto during a cricket game between the students and their fathers, he concludes that the answer to another question—how was the stiletto made to disappear?—will solve both this crime and the earlier one. For Yanks there may be a bit too much schoolboy and cricket jargon but on the whole this is an excellent debut novel, deserving all the accolades it has garnered since its first publication.

***

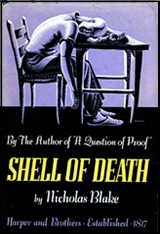

The title of the second Strangeways exploit and much of its plot are taken from an obscure (except to specialists) Jacobean melodrama. THOU SHELL OF DEATH (1936) is a quotation from Cyril Tourneur’s THE REVENGER’S TRAGEDY (1607), a play which becomes increasingly relevant as we progress through the book.

On a recommendation from his uncle, an Assistant Commissioner at Scotland Yard, Nigel travels to rural Somerset a few days before Christmas to investigate three threatening letters that have been sent at the rate of one a month to Fergus O’Brien, a World War I air ace who, somewhat like Lawrence of Arabia, has retired to the countryside.

The most recent letter prophesies that O’Brien will die on the day after Christmas, also known as Boxing Day and the Feast of Stephen, the day on which good king Wenceslas in the carol went out. The reclusive war hero is uncharacteristically hosting a house party over the holidays, a party consisting of a woman explorer whose life he had saved in Africa, her financially desperate brother, a shady roadhouse proprietor, O’Brien’s discarded mistress, and an old Oxford don who had been one of Nigel’s professors.

Sure enough, O’Brien is found shot to death on Boxing Day morning, and over the next few days there’s another death, this one by poison inserted in a peanut, and a near-fatal bludgeoning. Many chapters are filled with complex alternative theories of the crimes, propounded by Nigel and a Somerset officer and Inspector Blount of Scotland Yard, but the reasoning remains on a speculative level until Nigel travels to rural Ireland in search of O’Brien’s mysterious pre-war past.

SHELL is more of a full-blooded detective novel than A QUESTION OF PROOF, with a particularly brilliant “player on the other side†(although how this adversary came to know so much about the works of Cyril Tourneur remains unexplained) and abundant quotations and allusions ranging from the tale of Hercules and Cacus and the epistles of St. Paul through Shakespeare (and of course Tourneur) and finally a few of Day-Lewis’s contemporaries.

Nigel no longer guzzles tea by the potful as he did in his first outing but at one point, having missed his dinner, he snarfs a gargantuan impromptu meal—a pound or so of cold beef, ten potatoes, half a loaf of bread and most of an apple pie—-and later, just as in A QUESTION OF PROOF, he breaks into song during a wild auto chase.

American readers might be put off by the number of minor characters who speak in regional or ethnic dialects as if they were in a Harry Stephen Keeler novel, but at least the accents are more authentic than the ones HSK dreamed up. (*)

***

The poisoned peanut in the second Blake novel is (dare I say it?) a mere bag of shells compared with the murder method in the third. There were signs in that second book that Nigel was beginning to fall in love with Georgia the daredevil explorer. At the start of THERE’S TROUBLE BREWING (1937) they’re married. Nigel is still a consulting detective but has developed a sideline as an authority on poetry, and on the basis of his book on the subject he’s invited to deliver a lecture before the Literary Society in the Dorsetshire town of Maiden Astbury.

The Big Daddy of the place is the owner of the local brewery, whom, if I weren’t so fond of Bufo bufo, I’d describe as a toad of the first water. He bullies his wife and all but cuts her out of his will (which I don’t think possible under either English or American law, but we’ve seen before that Blake has zero interest in legal issues).

He also sexually harasses young women, requires his laborers to work inhuman schedules, makes life hell for his socially conscious younger brother, blackmails into silence the local doctor who has documented the brewery’s unsafe working conditions. He even beats his fox terrier! It’s because of this dog, who was found two weeks earlier in one of the brewery’s pressure vats, literally boiled to death, that the Big Daddy character prevails on Nigel to stay in Maiden Astbury for a while and investigate the animal’s murder.

Nigel spends the next day touring the beer factory and interviewing its principals but his detection is interrupted by the discovery inside the same pressure vat of a human skeleton, apparently that of Big Daddy, although Nigel and the local police inspector seem to be familiar with Conan Doyle’s THE VALLEY OF FEAR and the early Ellery Queen novels since they seriously consider the possibility that the boiled corpse is someone else.

Suspicion spreads among various characters and several highly speculative alternate theories of the crime are articulated. In due course come two more murders and a midnight climax in the eerie brewery that may remind some readers of a 1930s cliffhanger serial, although Blake is careful to keep Nigel from acting like a serial hero.

With each chapter prefaced by a literary quotation—from Shakespeare and Bacon and Ben Jonson through 19th-century figures like Byron and Coleridge and Dickens to the poet A.E. Housman, who had died in 1936—this is a fine example of the kind of detective novel whose earliest protagonist was Lord Peter Wimsey.

***

Blake’s fourth novel was the only book of his that became the basis of a feature-length film by a prestigious director. I’ll discuss both the book and the movie when I return to Blake later this year. His fifth novel was almost made into a movie by another prestigious director—or more precisely by a young man who quickly became one of the most prestigious directors of all time. When I take up Blake again I’ll tell that story too.

Thu 3 Feb 2022

REVIEWED BY MIKE TOONEY:

(Give Me That) OLD-TIME DETECTION. Autumn 2021/Winter 2022. Issue #58. Editor: Arthur Vidro. Old-Time Detection Special Interest Group of American Mensa, Ltd. 36 pages (including covers). Cover image: A Rumpole Christmas.

This issue of Old-Time Detection continues to maintain the usual high standards for the publication, being replete with perceptive book reviews and features that would be of interest to any mystery fan.

“Mystery Reviews” by Jon L. Breen has Breen, one of the sharpest detective fiction critics, finding R. D. Rosen’s Strike Three, You’re Dead a most agreeable mix of baseball and amateur detection — “may be,” he says, “the ultimate sports mystery.” For fans of Wall Street mysteries, there’s a “more-than-adequate British equivalent” in David Williams’ Advertise for Treasure.

In “The Paperback Revolution,” Charles Shibuk covers a lot of classic detective fiction ground with short but pithy assessments of some of the works of Eric Ambler (Journey Into Fear, 1940), Leslie Charteris (The Saint in New York, 1935), Agatha Christie (The Moving Finger, 1942), Joseph Harrington (Blind Spot, 1966, and The Last Doorbell, 1969), Baynard Kendrick (Out of Control, 1945), Ross Macdonald (The Underground Man, 1971), Ngaio Marsh (Overture to Death, 1939), Ellery Queen (There Was an Old Woman, 1943, and Calamity Town, 1942), Dorothy L. Sayers (Murder Must Advertise, 1933), and Rex Stout (The League of Frightened Men, 1935, and The Rubber Band, 1936).

Dan Magnuson offers us his tribute to the late J. Randolph Cox, not only a close friend but also a Nick Carter expert, and, among other good things, the author of books about Walter Gibson and Flashgun Casey.

A fine addition to the issue is an “Author Spotlight” by Michael Dirda focusing on Edmund Crispin, more often than not one of the most delightful detective fiction authors of the Golden Age. You’re not likely to find a more comprehensive yet concise essay on Crispin than this one.

In the “Christie Corner” by Dr. John Curran, the foremost living expert on the works of Agatha Christie, comes news of the publication of a non-Christie book (The Invisible Host, 1930), the plot of which some would say Agatha “borrowed” for And Then There Were None (1939); Curran, however, is more than a little skeptical and offers good reasons for his doubts. Since 2022 marks the 90th anniversary of The Thirteen Problems (USA title: The Tuesday Club Murders), a publisher has decided to “re-imagine” Miss Marple, even commissioning some non-crime writers to do the bloody deed — I mean, give us their interpretations of the character. Curran finishes by briefly noting a computer game featuring Hercule Poirot and yet another scrambled up short story collection “culled from throughout Christie’s career.”

This issue’s fiction selection is T. S. Stribling’s “The Mystery of the Choir Boy” (EQMM, January 1951), in which Dr. Poggioli gets involved in a scheme meant to hoodwink the public but which culminates in murder.

“‘Count the Man Down,’ A Nero Wolfe Pilot” by Bruce Dettman illumines the experimentation that Hollywood in the ’50s was performing in adapting well-known — meaning “hopefully it’ll make money since everybody’s heard of it” — quantities to the small screen. Inspired by the huge success of Perry Mason, the producers tried — and failed — to bring Rex Stout’s famous detective and his “assistant” to life (“pretty much a botched effort”). Only the actor playing Archie gets a thumbs up from Dettman, a rookie thespian who in a few years would become a TV icon.

“The Life and Death and Life of Sherlock Holmes” by Richard Lederer compactly outlines the career of the Sage of Baker Street and the adience-abience dilemma that confronted his literary creator.

Then come more in-depth book reviews of John Mortimer’s A Rumpole Christmas (2009), reviewed by Ruth Ordivar, a collection of five stories whose “quality more than makes up for the thin quantity”; Anthony Berkeley’s Murder in the Basement (1932), reviewed by Harv Tudorri, in which Roger Sheringham seeks “to get to the bottom of a problem and to prove it to my own satisfaction”; Agatha Christie’s Crooked House (1949), reviewed by Sheila M. Barrett, a story whose “elements are laid forth as the reader might expect from Christie’s expert hand”; Jon L. Breen’s Listen for the Click (1983), reviewed by Arthur Vidro, a sports/mystery novel that works just right; and Christie’s Murder in the Mews (1937), reviewed by Trudi Harrov, containing four stories that collectively manage to “hit the spot.”

“The Non-Fiction World of Ed Hoch” has the all-time master of the short detective story “Seeking the First Mystery Magazine,” from possible candidates like Old Cap. Collier Library and voluminous Nick Carter publications in the late 19th century through Detective Story and Mystery Magazine and, of course, Black Mask in the early years of the 20th century. As Hoch tells us, however, designating what was actually the first mystery magazine could come down to a matter of categorization.

“The Readers Write”: “Thanks for continuing to do this labor of love for all of us who enjoy the Good Old Days!”

. . . and finally there’s the Puzzle Page—and it’s a doozy.

___

If you’d like to subscribe to Old-Time Detection:

Published three times a year: spring, summer, and autumn. – Sample copy: $6.00 in U.S.; $10.00 anywhere else. – One-year U.S.: $18.00 ($15.00 for Mensans). – One-year overseas: $40.00 (or 25 pounds sterling or 30 euros). – Payment: Checks payable to Arthur Vidro, or cash from any nation, or U.S. postage stamps or PayPal. – Mailing address: Arthur Vidro, editor, Old-Time Detection, 2 Ellery Street, Claremont, New Hampshire 03743.

Web address: vidro@myfairpoint.net

Wed 22 Dec 2021

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

REVIEWED BY JIM McCAHERY:

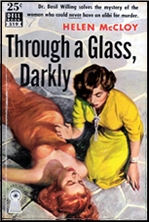

HELEN McCLOY – Through a Glass, Darkly. Basil Willing #8. Random House, hardcover, 1950. Dell #519, paperback, mapback edition, [1951]. Dell, paperback, date?

This is the eighth novel featuring psychiatrist-detective Dr. Basil Willing, recently returned from Japan after completing his military service. Willing is alerted by his soon-to-be fiancée and wife Gisela von Hohenems to the strange happenings surrounding Faustina Crayle at Brereton, a school for girls where they are both teachers — Gisela in German and Faustina in Art.

It would appear that Faustina has been seen bilocating more than once. When she is finally released from her teaching contract, Willing decides to investigate these “supernatural” appearances which he is convinced have. their roots in reality.

He soon learns that Faustina had been discharged from her first teaching position for the same reason. Further probing suggests that it is not just Faustina’s reputation that someone is out to destroy, and there are two deaths before a final confrontation.

This is probably the best use of the Doppelganger theme since Dorothy L. Sayers’ The Image in the Mirror. The title taken from Cor1nthians is very cleverly used here, but its significance does not become clear until the denouement.

The novel is an expansion of Miss McCloy’s 1948 short story of the same name which appeared in the September issue of EQMM.

– Reprinted from The Poison Pen, Volume 3, Number 3 (May-June 1980).