Search Results for 'Dorothy L. Sayers'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Wed 27 Jul 2011

PRIME TIME SUSPECTS

by TISE VAHIMAGI

Part 5.0: Theatre of Crime (US)

Taking its cue from 1930s and 1940s radio drama, the U.S. television play format (initially a live presentation) gathered strength during the 1950s. Presented in various anthology series, the form evolved from live performances to filmed episodes (as developments in broadcast technology progressed).

Unlike contemporary British television (BBC), with its roots in theatre (the stage), American television drew on professional elements from Radio and from Hollywood (when the latter saw fit to work for the small-screen). By the 1960s, some of the on-screen results were simply astounding.

The Crime and Mystery genre was represented not only by some outstanding individual plays presented in general anthology series (such as Studio One) but also by entire anthology collections dedicated to the theme. Unfortunately, most of these genre-based anthologies tended to feature ordinary television suspense yarns (usually concerning devious murderers or remorseful fugitives).

I have, therefore, omitted many of these anthologies (such as Hands of Destiny, DuMont, 1950-51; The George Sanders Mystery Theatre, NBC, 1957; Panic!, NBC, 1957) from this overview.

In the beginning, Studio One (aka Westinghouse Studio One; CBS, 1948-58) appeared to have only one thing going for it, a brutally realistic adaptation of Dashiell Hammett’s “Glass Key” (May 1949). But then, later in 1949, another Hammett appeared, “Two Sharp Knives”.

It was the beginning of a Studio One deluge, sweeping in with “The Room Upstairs” (1950), from Mildred Davis, “Shield for Murder” (1951), from William P. McGivern, “Nightfall” (1951), from David Goodis, “Mr. Mummery’s Suspicion” (1951), from Dorothy L. Sayers, and “The King in Yellow” (1951), from Raymond Chandler.

In 1952 they presented “The Devil in Velvet”, from John Dickson Carr, “They Came to Baghdad”, from Agatha Christie, “Stan, the Killer” and, later, “Black Rain” (1953), from Georges Simenon, “Little Men, Big World”, from W.R. Burnett, and “The Hospital”, from Kenneth Fearing. 1953 saw “Sentence of Death”, from Thomas Walsh. In 1954 came “Let Me Go, Lover”, from Charlotte Armstrong.

By 1955 this deluge was down to a trickle, with “Donovan’s Brain”, from Curt Siodmak, and, in 1956, “The Talented Mr. Ripley”, from Patricia Highsmith. The final drops (genre-wise) were squeezed out with “First Prize for Murder” (1957), from John D. MacDonald, and “A Dead Ringer” (1958), from James Hadley Chase. Along the way, Studio One’s two-part “The Defender” (1957), by Reginald Rose, became the inspiration for the excellent 1961-65 series The Defenders (CBS).

Taking its title literally, Suspense (CBS, 1949-54) showcased stories by Cornell Woolrich, John Dickson Carr, Craig Rice, Stanley Ellin, Robert Louis Stevenson, Edgar Allan Poe, Joel Townsley Rogers, Arthur Conan Doyle, John Collier, Geoffrey Household, Georges Simenon, Wilkie Collins, and many others. But before the mouth-watering begins, it should be noted that these plays were broadcast live and therefore less than a third of them survive.

[Places like The Museum of Broadcast Communications in Chicago, Museum of Television and Radio in New York and The Paley Center for Media in Los Angeles may have viewing copies of some surviving episodes. Then, there’s always the Internet Archive – Moving Images – Television to explore: http://www.archive.org/details/television.]

Recipient of a Special Edgar Award in 1951, The Web (CBS, 1950-54) was a live New York series presenting stories from the works of the Mystery Writers of America (MWA). Tantalizing in the extreme, especially with so little to go on in terms of detailed episode credits, one can only imagine (fantasize, even) the possible selection of genre stories translated here for television.

Living up to its name, Danger (CBS, 1950-55) certainly satisfied its viewers with moments like Philip MacDonald’s “The Green and Gold String” (1950), John Dickson Carr’s “Charles Markham, Antique Dealer” (1951), Anthony Boucher’s “Mr. Lupescu” (1951), William L. Stuart’s “Blackmail” (1953) and Daphne du Maurier’s “The Birds” (1955). At the same time the series also promoted the early careers of directors Sidney Lumet and John Frankenheimer as well as actor James Dean.

Another live and prestigious series was Robert Montgomery Presents (NBC, 1950-57) which invested in some noteworthy episodes, particularly during the earlier seasons. Included were presentations based on works by Dorothy B. Hughes, Cornell Woolrich, Raymond Chandler (“The Big Sleep”, 1950), Wilkie Collins, Mary Roberts Rinehart, Hemingway (“The Killers, 1955) and Fredric Brown.

Inner Sanctum (NBC, 1953-54) featured stories based on the popular 1940s radio series, which included Edgar Wallace as story source for “The Lonely One” (1954) and author John Roeburt as a contributor of various teleplays.

Based also on a popular radio series was the earlier Lights Out (NBC, 1949-52). Similar in atmosphere and theme to Inner Sanctum, it presented stories by Edgar Allan Poe (“The Fall of the House of Usher”, 1949; “The Masque of the Red Death”, 1951; “The Pit”, 1952), August Derleth (“Rendezvous”, 1950), Dorothy L. Sayers (“The Leopard Lady”, 1950), Ira Levin (“Leda’s Portrait”, 1951), Fredric Brown (“The Pattern”, 1951) and Cornell Woolrich (“Nightmare”, 1952).

Filmed at Elstree in England for NBC, Douglas Fairbanks Jr. Presents (NBC, 1953-57; ITV/UK from 1955) presented one particular episode which is worth being celebrated by fans of the genre because it represents the only proposal (to my knowledge) for a Bulldog Drummond TV series: the half-hour pilot episode “The Ludlow Affair” (NBC, 1957), with Robert Beatty as our hero and the scene-stealing Michael Ripper as his sidekick.

Climax! (CBS, 1954-58) got itself off to an enterprising start with Chandler’s “The Long Goodbye”, starring Dick Powell again as Marlowe, and followed it up quickly with Bayard Veiller’s “The Thirteenth Chair”, Fleming’s “Casino Royal” and Lucille Fletcher’s “Sorry, Wrong Number”.

The rest of its TV treasures consisted of works by Mary Roberts Rinehart, Eric Ambler, A.A. Fair [Erle Stanley Gardner], John D. MacDonald, George Hopley [Cornell Woolrich], Patricia Highsmith, Ursula Curtiss, Charlotte Armstrong, Ed McBain [Evan Hunter], and John Dickson Carr.

Warner Brothers Presents (ABC, 1955-57) was the umbrella title for Conflict (ABC, 1956-57), an anthology presenting compositions by Frederick Brady and Thomas Walsh as well as the first pilot (“Anything for Money”, 1957) for the influential 77 Sunset Strip (ABC, 1958-63).

Lux Video Theatre (CBS, 1950-54; NBC, 1954-57) ran for some seven years, but the NBC seasons were the ones that were of the most interest. During this period the series began featuring teleplay adaptations based on screenplays from some notable Hollywood movies. For instance, there was “Double Indemnity” (1954), “So Evil My Love” (1955), “Shadow of a Doubt” (1955), “My Name is Julia Ross” (1955), “The Suspect” (1955), “Suspicion” (1955), “Ivy” (1956), “Witness to Murder” (1956), “Mildred Pierce” (1956), “The Guilty” (1956) and “The Black Angel” (1957).

The first genre anthology to be filmed by a major studio (Universal), Alfred Hitchcock Presents (CBS, 1955-60; NBC, 1960-62) has over the decades acquired something of a mystique of its own.

Utilizing the art and craft of many screenwriters, big-screen actors and like-minded directors, the series’ producers (Joan Harrison and, later, Norman Lloyd) provided a wonderful insight into the workings of the famed Hitchcock (his Shamley Productions produced the series for which he was executive producer). Hitchcock was also savvy enough to explore the work of a vast range of lesser-known genre authors.

Story sources for Alfred Hitchcock Presents include Lillian de la Torre, C.B. Gilford, Michael Arlen, Norman Daniels, Richard Deming (1915-1983), Henry Slesar, Lawrence Treat, Roy Vickers, Harold Q. Masur, Brett Halliday [Davis Dresser], Margaret Manners, Helen Neilsen, Anthony Gilbert [Lucy Beatrice Malleson], Dorothy Salisbury Davis, and Ed Lacy.

It may not come as too much of a surprise to many readers that the highly-praised 1960 film Psycho was made at Universal by Hitchcock’s TV team, conspicuous by the striking monochromatic imagery of Shamley’s cinematographer John L. Russell.

The series was revived by NBC (1985-86) and featured colorized Hitchcock intros of the now-deceased host from the original 1950s show. Befittingly macabre or merely mindless? Then, USA Cable Network continued the title (1987-88) with some additional episodes.

Hitchcock’s Shamley Productions turned to NBC for Suspicion (NBC, 1957-58), even while Alfred Hitchcock Presents was still running over on CBS. The series consisted half-and-half of filmed (Shamley) and live presentations, including Woolrich’s “Four O’Clock”, Helen McCloy’s “The Other Side of the Curtain”, and the rarely-seen “Voice in the Night” (1958) by William Hope Hodgson. “Eye for an Eye” (1958) was the pilot episode for Ray Milland’s 1959-60 private eye series Markham (CBS).

Kraft Television Theatre became Kraft Mystery Theatre (NBC) for the summer of 1958. The series presented many fine and unexpected works, most notably Ed McBain’s [billed as Evan Hunter] “Killer’s Choice”, the Larry Cohen-scripted “The Eighty Seventh Precinct” [from the McBain novels] and “Night Cry” [from the 1948 novel by William L. Stuart; filmed in 1950 as Where the Sidewalk Ends]. Kraft Television Theatre was the last of the live shows when it faded in 1958, everybody else having already turned to filmed recordings.

There is one particularly interesting episode of the anthology Pursuit (CBS, 1958-59): “Epitaph for a Golden Girl” (1959), adapted by Lorenzo Semple Jr. from a short story by Ross MacDonald. The story originated in EQMM in June 1946 as “Find the Woman,” with MacDonald writing as Kenneth Millar. In the Pursuit adaptation, star Michael Rennie’s private detective is now called Rogers (instead of Lew Archer).

In April 1959, Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse (CBS, 1958-60) presented writer Paul Monash’s two-part “The Untouchables” which served as a suitably violent introduction to the popular and controversial series The Untouchables (ABC, 1959-63). The series helped launch the action-filled 1959 to 1962 television gangster phase (to be a later Part in this TV history overview).

A second Part of this “Theatre of Crime (US)” will follow shortly, concluding the US history of the genre anthology from the 1960s onwards.

Note: The introduction to this series of columns by Tise Vahimagi on TV mysteries and crime shows may be found here, followed by:

Part 1: Basic Characteristics (A Swift Overview)

Part 2.0: Evolution of the TV Genre (UK)

Part 2.1: Evolution of the TV Genre (US)

Part 3.0: Cold War Adventurers (The First Spy Cycle)

Part 3.1: Adventurers (Sleuths Without Portfolio).

Part 4.0: Themes and Strands (1950s Police Dramas).

Part 4.1: Themes and Strands (Durbridge Cliffhangers)

Wed 15 Jun 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[8] Comments

SUSPENSE — WITH A HITCH

Cornell Woolrich’s Rear Window and Other Stories

A Review by Curt J. Evans

CORNELL WOOLRICH – Rear Window and Other Stories. Penguin, paperback, 1994. First published as Rear Window and Four Short Novels: Ballantine, paperback original, 1984.

There have been so many Cornell Woolrich short story collections collected over the years that one can enter into an agonizing state of suspense just trying to decide which of these collections to buy. Fortunately I can assure you — if you do not know it already — that this particular collection is a corker.

Interestingly, not only is the title short story (“Rear Window,†1942) associated with that cinematic master of suspense, Alfred Hitchcock, so are the collection’s additional four tales: “Post-Mortem†(1940), “Three O’Clock†(1938), “Change of Murder†(1936) and “Momentum†(1940). Indeed, I strongly suspect this is why they are collected here in this volume.

Rear Window of course, is one of Hitchcock’s great films, while “Post-Mortem,†“Change of Murder†and “Momentum†all were filmed for the memorable television series Alfred Hitchcock Presents (“Change of Murder†as “the Big Switchâ€) and “Three O’Clock†was directed by Hitchcock himself for the fifties television series Suspicion.

I have seen all of these adaptations bar “Three O’Clock†and all are first class mystery entertainment. (“Three O’Clock†was retitled “Four O’Clock” and shown as the first episode of Suspicion on 30 September 1957. I have never seen an episode of this series.)

Woolrich’s “Rear Window†is an excellent story, but for me it has been rather upstaged by the film. Not so the rest, however. Of the remaining four stories the most minor is the early Woolrich tale “Change of Murder,†though it a clever little piece with a nice twist in the tail (it also is the shortest of the five by far).

“Momentum†is a strong work (again with a fine twist), but my absolute favorites in this collection are “Post-Mortem†and “Three O’Clock.†Though I have great admiration for the droll television adaptation of the former (with its excellent performances by Joanna Moore, Tatum O’Neal’s mother, and Steve Forrest, a brother of Dana Andrews), I found the story easily stands on its own as a biting and ironic domestic suspense classic rather on the order of Dorothy L. Sayers’ brilliant “Suspicion.†Quite a bit of plot complexity is packed into this tale (which was streamlined in the adaptation).

As indicated above, “Three O’Clock†was completely new to me, and I found it a powerful screw turner of tension. Again the tale has a domestic setting, but where “Post-Mortem†is black comedy, “Three O’Clock†is just blackly grim — and powerfully and memorably so.

Suspense is remorselessly (if at times improbably) drawn out and the twist, when it came, took me totally by surprise. I hesitate to say anything in detail about the plot for those who have not read the tale or seen the television adaptation. To those people: just read it!

Rear Window and Other Stories seems to me a great place to start a literary relationship with the great master of suspense Cornell Woolrich. It is also one to return to again and again … if you dare. Unpleasant dreams!

Thu 9 Jun 2011

WE ARE ALL SENTIMENTALISTS NOW:

Leonard Cassuto’s Hard-Boiled Sentimentality:

The Secret History of American Crime Stories

by Curt J. Evans

Over the last twenty years feminist literary scholars have leaped into the field of mystery criticism with great energy and enthusiasm; and they have had a remarkable impact on it. In Great Britain, such academic authorities as Gill Plain, Susan Rowland and Merja Makinen have written perceptive revisionist studies on British Golden Age “Crime Queens†(Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, Margery Allingham and Ngaio Marsh), defending them from the traditional (usually male) criticism, dating back to Raymond Chandler and Edmund Wilson in the 1940s and prevalent through the early Marxist-influenced academic monographs of the 1970s, that their work is insipid, reactionary drivel, in contrast with the admirable, socially progressive and genre transcending American hard-boiled fiction most famously associated with Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler himself.

This scholarly feminist emphasis on the Crime Queens, while important in revising earlier masculinist views of these authors, has led to the elevation of an increasingly commonplace view within academia, namely that the mystery genre in Britain during the Golden Age was essentially feminine, representing a purportedly distinct and uniquely female set of values, such as the privileging of feelings and intuitions over material detail (i.e., psychology over footprints and timetables), a preference for cerebration over fisticuffs as the way of reaching solutions to problems and an emphasis on domestic detail and the inter-connectedness of individuals. “All in all,†emphatically concludes Susan Rowland in a representative statement from a recent essay, “the golden age form is a feminized one.â€

[Susan Rowland, “The ‘Classical’ Model of the Golden Age,†in Lee Horsley and Charles A. Rzepka, eds.,

A Companion to Crime Fiction (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), 122.]

Thus portrayed, “feminine†English Golden Age detective fiction starkly contrasts with the “masculine†hardboiled form that frequently has been taken to represent American detective fiction during this period (roughly 1920 to 1939) — though the critical estimation of English Golden Age detective fiction (or, to be more precise, the four women authors often portrayed as nearly entirely representing it) has been considerably raised.

However, another feminist literary scholar — this time an American, Catherine Ross Nickerson — has pointed out in an important 1998 study, The Web of Iniquity: Early Detective Fiction by American Women, that detective fiction in the United States was not actually a strictly masculine preserve, a playground for the tough guys. Rather, Nickerson has shown, an indigenous American tradition of female-authored crime fiction existed well back into the nineteenth century.

One of the writers she discusses, Mary Roberts Rinehart, was active and extremely popular in the United States all though the Golden Age (indeed, she was much more significant at this time than Raymond Chandler, who only published his first novel in 1939, at the very tail-end of the Golden Age, confining himself before that to pulp short stories).

But although Professor Nickerson helped remind her academic colleagues that women mystery writers with their own narrative style and literary concerns not only existed but were much read in the United States in the 1920s and 1930s, it remained for Professor Leonard Cassuto to do something that no other academic had yet done: perceive the American hardboiled detective novel itself as feminized.

[Academic scholars continue to mostly overlook detective novelists in both the United States and Great Britain who did not write in the hardboiled style and were not women, but that is the subject for another essay!]

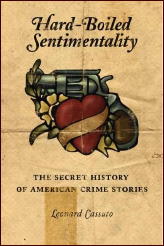

Leonard Cassuto’s Hard-Boiled Sentimentality: The Secret History of American Crime Stories (Columbia University Press, 2008) is one of the most highly praised academic crime literature monographs of the last decade. “Superb…fresh insights on every page,†declares Alan Trachtenberg of Yale University.

Not to be outdone is crime writer Julia Spencer-Fleming, who provides a blurb that is surely one to die for: “Hard-Boiled Sentimentality is a nonfiction epic that reads like the best genre fiction, tracing the bloodlines of crime fiction from Sam Spade to Hannibal Lecter. Cassuto’s scholarship is impeccable; his narrative voice magnetic. A must-read for every student of genre fiction and the go-to source for the evolutionary history of the genre.â€

Whew! Is it really as good as all that? In my view, not quite; though Cassuto makes an interesting (if not invariably persuasive) argument and his writing is comprehensible and refreshingly jargon-light, not something that can be said for many of the academic monographs in this field. Hard-Boiled Sentimentality often is quite insightful and for those interested in hardboiled fiction it should make rewarding reading.

[Despite the zealous claim that

Hard-Boiled Sentimentality reads as grippingly as the best crime novels, sentences like “this refusal to speculate aligns Spade with some of the reformist political positions of the Progressive era†do not trip off the tongue. To be fair to Cassuto, however, I cannot recall any academic monograph that reads just like a crime novel.]

Leonard Cassuto contends that rather than being “masculinist†tales of unfeeling lone tigers prowling in the asphalt jungle, hard-boiled novels in reality are closely related to women’s sentimental domestic fiction of the nineteenth century, which “celebrates the reliable and nourishing social ties that result when people extend their sympathy to others around them.â€

In Cassuto’s view, hard-boiled tales “engage with a domestic sentimentalism born of a specific historical period†and it is this “engagement with the nineteenth-century sentimental†that “shapes the history and evolution of the hard-boiled from its inception to the present day.†“Inside every crime story is a sentimental narrative that’s trying to come out,†declares Cassuto provocatively. “Sentimentalism invented the American crime novel.â€

Over the course of his study, which extends from the 1920s to the present day, Cassuto explicates the key role he sees sentimentalism as having played in the shaping of the American crime tale. Chapter One deals with the influence exercised on the hard-boiled school of crime writing by mainstream novelists Theodore Dreiser and Ernest Hemingway.

Chapter Two looks at Dashiell Hammett. Relying on his reading of The Maltese Falcon (and to a lesser extent Red Harvest and The Dain Curse), Cassuto argues that Hammett portrays “sentimentalism in ruins: a world of self-interested individuals cut loose from family ties and family obligations, who have abandoned sympathy to chase the dollar.â€

However he emphasizes that in The Maltese Falcon tough-as-nails detective Sam Spade struggles between “self-interest and sympathy†and that in The Dain Curse the Continental Op “shows genuine concern for his young charge [Gabrielle Leggett].â€

Chapter Three sees Cassuto taking on “Depression Domesticity,†primarily through James M. Cain’s Mildred Pierce and Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep and The High Window.

With its family saga of a deluded mother and her deceiving daughter, writes Cassuto, Mildred Pierce allows James M. Cain to bring “the sentimental and the hard-boiled into the same house.†It offers readers “the key to the hard-boiled engine-room.â€

Chandler’s detective Philip Marlowe, for his part, is in Cassuto’s view driven primarily by a need to put broken houses back together, restoring families to that portion of harmony still possible in 1930s America. As an author, asserts Cassuto, Chandler was “in quixotic pursuit of a family ideal that was being threatened during the Depression, when financial hardship broke many families apart.â€

Chapter Four, which takes us past World War Two and into the 1950s and the Cold War, sees Cassuto considerably expanding his analytical net, taking in a wider range of novels, including those by Chandler, Mickey Spillane, David Goodis, John D. MacDonald, William P. McGivern, Wade Miller, “John Evans†(Howard Browne), Gil Brewer and Cornell Woolrich.

“Working from the model provided by Raymond Chandler,†explains Cassuto, “postwar crimefighters become passionate and involved defenders of home and hearth.†Cold War paranoia and the desire to restore traditional gender roles after global conflagration had menaced world order combined to create the fetching but fearsome femme fatale, a creature in Cassuto’s view that is most notable for her refusal to accept what was seen as her natural role in the social order, that of domesticated wife and mother.

“A veritable army of unpredictable femmes fatales, armed and dangerous and set to destroy home and community, swarms out of the crime stories of the 1950s,†Cassuto writes colorfully. He is especially interesting here on the hard-boiled novel’s treatment of lesbians and transsexuals, who represented the ultimate in “female†transgression.

Even Cassuto’s creativity at finding sentimentality in every hard-boiled cavity he searches is stymied by those deviant and demented darlings of modern critics, Patricia Highsmith and Jim Thompson, however; and in Chapter Five, “Sentimental Perversion,†he shows how these compellingly idiosyncratic authors subversively undermined sentimentalism at every opportunity.

To be sure, sentimentality makes a considerable comeback in Chapter Six, where Cassuto looks at the work of Ross Macdonald, John D. MacDonald and (to a much lesser extent) Robert B. Parker. Anyone familiar with Ross Macdonald’s novels knows they changed over time, as Macdonald shook off the influence of Chandler (who was quite cutting in his appraisal of the younger man’s work) and allowed his own personal preoccupations to take hold of his narratives.

Making use of Tom Nolan’s fine biography of Macdonald, Cassuto is able to show how the author’s family problems meshed with the therapeutic culture of the 1960s to lead Macdonald to produce book after book on household dysfunction and the generation gap, with Macdonald’s series detective, Lew Archer, acting as a sort of family therapist (or as Cassuto writes, “a kind of walking vessel for collective guilt†and “an everyman of sympathyâ€).

For Cassuto Ross Macdonald “stands as perhaps the most sentimental of all hard-boiled novelists because he understands family ties in the same way the sentimental writers did a century before him.†Similarly, Cassuto believes the robust if offbeat home life (aboard a Fort Lauderdale houseboat called the Busted Flush) of John D. MacDonald’s detective Travis McGee firmly affiliates this author’s work with the sentimental side of life, since his detective is not office-centered like Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe.

Dealing with, respectively, female private eyes and race in the hard-boiled novel, Chapter Seven and Eight feel somewhat tacked on, but Cassuto returns in full force with a discussion of the serial killer and the crime novel in his monograph’s final chapter. Contrary to what we might think, serial killer novels also reflect sentimentalist hegemony, according to Cassuto. The serial killer should be understood as “an anti-family man,†Cassuto declares. “He is purely anti-sympathy, anti-domesticity, anti-sentimentality.†And opposing him is the increasingly sensitive and domesticated detective.

At one point in his book, Cassuto forcefully criticizes scholars’ “static and stereotyped conception of hard-boiled masculinity.†He rightly notes that this conception has arisen to a great extent from ingenuous readings of Raymond Chandler’s polemical 1946 essay, “The Simple Art of Murder,†which stridently emphasizes the tough masculinity of hard-boiled heroes by “feminizing the genteel detective story tradition.â€

To be sure, other critics before Cassuto have discerned a certain amount of hollow chest-beating bravado in Chandler’s essay. The great centenarian scholar Jacques Barzun, for example, noted forty years ago in the introduction to his and Wendell Hertig Taylor’s A Catalogue of Crime (Harper & Row, 1971) that Chandler in notable ways was himself a “sentimental [emphasis added] tale spinner†(p.11), whatever claims he made to the contrary in “The Simple Art of Murder.â€

Still, in forcefully challenging the “static and stereotyped conception of hard-boiled masculinity†with his lengthy study Cassuto deserves our praise. Nevertheless, I think that his admirable zeal to revise error sometimes pushes Cassuto to overstate his case, rendering an over-sentimentalized (or overly-feminized) interpretation of the hard-boiled crime novel.

Cassuto’s coverage of hard-boiled fiction in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s is sparser than I would have expected from an author advancing such an ambitious, overarching thesis. A number of significant tough crime writers of the period are short-shrifted (Raoul Whitfield) or ignored entirely (Jonathan Latimer).

Despite his fine discussion of Mildred Pierce, never does Cassuto convince me that James M. Cain’s admired novel truly is “the key to the hard-boiled engine room†(on the other hand, it is the work that most strongly supports his thesis). Does Mildred Pierce unlock Jonathan’s Latimer scabrously humorous The Lady in the Morgue (its repertoire includes necrophilia jokes about the lady missing from the morgue), for example?

While Cassuto provides some analysis of how James M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice and Double Indemnity (as well as Horace McCoy’s They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?) fit into his thematic structure, he largely omits consideration of the short stories of Hammett and Chandler, as well as Hammett’s novels The Glass Key and The Thin Man and Chandler’s novels Farewell, My Lovely, The Lady in the Lake and The Little Sister. (Playback is not here either, but who can really complain about that.)

These are significant omissions when one considers the small output of novels from the hard-boiled twin titans. In his entry on the novel in 1001 Midnights, Francis M. Nevins has written of The Glass Key that “its third-person narrative voice … is so objectively realistic and passionlessly impersonal that it seems to draw an impenetrable shield between character and reader.â€

Does Cassuto find sympathy in The Glass Key? In regard to Chandler, are his novels Farewell, My Lovely and The Lake in the Lake, published about the same time as The Big Sleep and The High Window, about Marlowe as a fixer of broken families? It would have been nice to see Cassuto’s thoughts on how these particular novels develop his themes.

[Bill Pronzini and Marcia Muller, eds.,

1001 Midnights: The Aficionado’s Guide to Mystery and Detective Fiction (Arbor House, 1986), 335.

In

Hard-Boiled Sentimentality, Chandler’s

The Big Sleep is discussed on a dozen pages,

The High Window on a half-dozen and

The Long Goodbye on three, while

Farewell, My Lovely is mentioned once (and this only in reference to its 1940s sales) and

The Lady in the Lake and

The Little Sister no times at all.

While doubtlessly

The High Window better illustrates Cassuto’s sentimental domesticity thesis than, say,

Farewell, My Lovely (where in my reading the strongest sentimental feelings are directed at single men),

The High Window certainly is not inherently a more “important†book in the Chandler canon than

Farewell, My Lovely. (Indeed, most critics clearly deem

Farewell, My Lovely to be markedly superior to

The High Window as a piece of literature.)

Similarly, Cassuto discusses Hammett’s

The Maltese Falcon on nearly thirty pages,

Red Harvest on seven and

The Dain Curse on six, while failing to mention the highly-praised

The Glass Key. Certainly

The Glass Key is considered a richer work than

The Dain Curse, which is almost universally regarded as Hammett’s poorest novel.]

Further, Cassuto’s attribution of causality for the way the narratives develop in the Hammett and Chandler novels he does write about sometimes is debatable. For example, Hammett’s vivid fictional world of grasping, self-interested and self-regarding individuals may owe more to the author’s engagement with Karl Marx than with Harriet Beecher Stowe.

Similarly, it seems to me that much of the thematic content in Chandler’s novels is derived from his marked resentment (personal, not ideological) of the idly wealthy and his deep sense of masculine honor. In my view, Marlowe’s sympathy in The Big Sleep is reserved for old General Sternwood, not his corrupted daughters.

Any repairing of the General’s home necessarily involves driving the insanely murderous and nymphomaniacal Carmen Sternwood from its precincts. (It is important to recall here the famous image of the stained-glass window in the Sternwood home depicting the knight battling the dragon, i.e., serpent — the serpent in the Sternwood home is Carmen, who even hisses at one point.)

As the critic Clive James has perceptively noted, “Carmen is the first in a long line of little witches that runs right through the [Chandler] novels, just as her big sister, Vivian, is the first in a long line of rich bitches who find that Marlowe is the only thing money can’t buy.â€

[Clive James, “Raymond Chandler,†in

As of this Writing: The Essential Essays, 1968-2002 (W. W. Norton, 2003), 204.]

Marlowe (who assuredly represents his creator) does not expend a lot of sentiment or sympathy either on the little witches or the rich bitches, those fallen temptresses and potential destroyers of men.

Certainly Chandler’s little witches are those les belle dames sans merci of hardboiled mystery, the femmes fatales (they appear — quite memorably — in Farewell, My Lovely and The Lady in the Lake as well, novels Cassuto does not discuss).

This fact alone leads me to question Cassuto’s assessment of the femme fatale primarily as a 1950s phenomenon. Cassuto himself admits that The Maltese Falcon offers a prominent example of the femme fatale, but the willful creature also rears her lovely head, as indicated above, numerous times in the works of Raymond Chandler, not to mention forties film noir, as well as other hard-boiled tales by the many 1940s writers not discussed by Cassuto.

Surely the explosion of the femme fatale phenomenon in this period was set off in part simply by the paperback revolution and the dramatic discovery that more explicit sexualization of women helped sell hardboiled books to male readers. In his book Hard-Boiled America, Geoffrey O’Brien perceptively highlights the impact of World War 2 in this context:

Wars in America have generally led to a relaxation of sexual censorship; for instance, the public acceptance of

Penthouse and

Hustler can probably be traced to the Vietnam War. Likewise the returning GIs of the 1940s craved stronger stuff than Betty Grable pinups…. With all the energy of an industry undergoing rapid development, the paperbacks — free of the constraints that hampered movies and radio — resolutely pushed the limits…. Encouraged by rising sales figures, [paperbacks] were no longer playing by the same rules (An illustrator whose career began in the postwar period recalls, “The word went out — get sex into it somehow.â€)

[Geoffrey O’Brien,

Hard-Boiled America (Da Capo Press, 1997) (expanded edition; originally published 1981).]

In short, sometimes hardboiled fiction surely engaged more directly with sexuality than sentimentality. (Certainly the lurid paperback covers did.) In Chandler’s case, the continual resort to the device of the femme fatale appears to have arisen more out of personal issues than national social and economic concerns (as does the distaste for homosexuals Chandler expresses though Marlowe in The Big Sleep), so once again Cassuto’s approach (e.g., traditional family rhetoric and the Cold War made them do it) seems overly mechanistic.

It should be noted that where it supports his thesis that a given hardboiled author is sentimental (Ross Macdonald in this case), Cassuto does resort in part to personal biography for answers as to why the author wrote as he did. Doing so makes his argument more persuasive (indeed, the Ross Macdonald section is one of the strongest in the book).

Sometimes Cassuto can be heavy-handed in his approach to causal factors. Could The Maltese Falcon or The Big Sleep have come into existence without Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, which observed the role self-interest played in guiding human endeavor, or his The Theory of Moral Sentiments, which analyzed sympathy?

Apparently they could not have, according to Cassuto. “Adam Smith may be considered the founding father of both sympathy and the hard-boiled attitude at the same time,†Cassuto rather breezily pronounces. “Smith published perhaps the foundational hard-boiled text, The Wealth of Nations, in 1776…. But Smith was already an expert on sympathy at the time he wrote his anatomy of capitalistic individualism; in 1759 he wrote The Theory of Moral Sentiments.â€

Such speculation led me idly to wonder how it is that Adam Smith never wrote a hardboiled crime novel. Had he done so, it inevitably would have been called, one imagines, The Invisible Hand.

[If Adam Smith is the “founding father†of sympathy, where does Jesus Christ fit into the picture?]

Despite these criticisms on my part, I think Cassuto has a valuable thesis overall. Academic analysts have tended to overly polarize male hard-boiled authors and female crime fiction writers (as well as traditional male detective novelists).

Thus I would recommend the perusal of Hard-Boiled Sentimentality by those interested in better understanding crime fiction. Yet I must also add a few more criticisms of the book that are of a different nature, stemming from Professor Cassuto’s evident lack of familiarity with the history of the mystery genre on certain points. (He is by no means alone among academic scholars in this regard.)

First, although he references Catherine Ross Nickerson’s The Web of Iniquity, rarely does Cassuto mention women crime writers before 1970 (Patricia Highsmith is the notable exception). In her review of Hard-Boiled Sentimentality, Sarah Weinman criticized Cassuto’s omission of Dorothy B. Hughes’ In a Lonely Place (1947) as “particularly startling†because “this novel seems to prove Cassuto’s thesis conclusively.â€

[Sarah Weinman, “Sentimental Tough Guys,â€

Los Angeles Times, 17 October 2008. Since in a footnote Cassuto briefly refers to the author’s handling of a serial killer in

In a Lonely Place, his failure to integrate the novel into the main body of his study clearly is deliberate, not inadvertent.]

I understand that Cassuto presumably wanted to focus on male hard-boiled writers rather than female ones, because the response to the inclusion of such a writer as Dorothy B. Hughes might well have provoked the response, “of course she wrote with sympathy, she was a woman!â€

Yet the omission of so many women writers does leave a sort of vacuum on those occasions when the author makes rather sweeping statements. When Cassuto writes that the “male heroes of most fifties crime novels … assume the protective role that women played in sentimental fiction of the previous century,†I could not help wondering what was going on in the fifties crime novels written by women. (In the works of women writers of 1950s “psychological suspense,†for example, one cannot always be sure of those “male heroes.â€)

Second, Cassuto, like most academic literary scholars, perpetuates the myth that Raymond Chandler cared nothing for plotting. In doing so he ironically relies mostly on Chandler’s “The Simple Art of Murder†essay, though elsewhere, as noted above, he chastises other scholars for unquestioningly accepting it. (He also digs up the old chestnut about Chandler not knowing who killed the chauffeur in The Big Sleep when questioned by Howard Hawks and William Faulkner, who were adapting the book to film).

Chandler “rejects the puzzle-whodunit because it’s unrealistic†and “turned away from the intricate plots of the likes of Ellery Queen and S. S. Van Dine because they’re too intellectual to activate the power of sympathy,†asserts Cassuto.

In a 2006 article in the Wall Street Journal, Cassuto is even blunter on this matter. “Raymond Chandler was the rare mystery writer who didn’t care whodunit,†Cassuto peremptorily pronounces in the first sentence of the article. Near the end of it, he asserts that “Chandler’s artistic impulse turns on his rejection of the puzzle mystery.â€

Though Cassuto is hardly alone in diminishing Chandler’s interest in the puzzle mystery (indeed, both Chandler’s biographers do it), he is wrong in doing so. Chandler read and enjoyed the traditionalist British detective novelists R. Austin Freeman and Freeman Wills Crofts (though he hated the debonair gentleman sleuths of the British Crime Queens and thought Agatha Christie was unfair to the reader), envied the plotting skill of Perry Mason creator Erle Stanley Gardner and composed, in the same decade as he wrote “The Simple Art of Murder,†a set of rules for writing mystery fiction that in many respects is as orthodox as those famously devised by Englishman Ronald Knox.

Further, for someone who purportedly “didn’t care whodunit†and rejected the puzzle mystery, Chandler perversely composed several well-plotted detective novels — praised by the orthodox critic Jacques Barzun — including Farewell, My Lovely, The High Window and The Lady in the Lake.

To be sure, The Big Sleep, his first mystery novel, does have, as scholars so often note, its share of plotting problems (I have never been too sure about that pesky chauffeur’s demise either); but that does not take away from the fact that several of his other novels are impeccably plotted. Chandler found plotting hard to do and groused about doing it, but he never rejected it and he often performed it admirably.

[Leonard Cassuto, “The Hero is Hard-Boiled,â€

Wall Street Journal, 26 August 2006. In his critical study

Raymond Chandler (Twyane, 1986), William Marling observes that Chandler’s novels after

The Big Sleep reveal the author’s “increased attention to plot.â€

He notes that Chandler “often came close to the ‘whodunit’ style of English mystery….than he cared to admit†(p. 104). For more on this subject see my forthcoming essay, “‘The Amateur Detective Just Won’t Do’: The Straight Dope on Raymond Chandler and British Detective Fiction.â€]

Third, Cassuto misunderstands the economics of book publishing in the years before the consummation of the paperback revolution. In Hard-Boiled Sentimentality, Cassuto describes The Big Sleep‘s selling of 12,500 copies as a “rocky debut.†(In his Wall Street Journal article, he earlier characterized such a sale as “meager.â€)

Riffing off this point, he concludes that the novel did not “find an audience†until 1943, when it was published in paperback and sold nearly a half-million copies. But in actuality, hardcover sales of a mystery novel title totaling to 12,500 copies was quite impressive in that era, a time when frugal people mostly borrowed mystery fiction (as opposed to “serious literatureâ€) from rental libraries.

Since presumably libraries purchased a great many of those 12,500 books sold, many thousands more than that number would have read the book in the four years that elapsed before The Big Sleep was published in paperback.

Finally, Cassuto’s references to the classical, puzzle-oriented detective novels of the Golden Age tend to be slighting and misinformed. Cassuto, who so forcefully critiques stereotype in the portrayal of hard-boiled fiction, tends himself to reach for stereotypes when using traditional detective fiction as a foil for the tough (yet tender) stuff.

“Hammett’s detective novels departed from genre tradition by presenting a story — and a set of social problems — unenclosed by a drawing room, a country estate, or any other discrete space,†writes Cassuto, relying on the well-worn but overstated notion that the narratives in traditional detective novels of the Golden Age are invariably confined within what are essentially enclosed stable spaces, usually country houses or villages.

Elsewhere, Cassuto passingly declares that hard-boiled novels “supplanted†puzzle-oriented Golden Age mysteries. While admittedly it is true that the rise of the hard-boiled school was one of the factors that helped break the puzzle’s hegemony over Golden Age crime literature, when (or even whether) hard-boiled tales “supplanted†puzzle mysteries is another question.

To state the most obvious example, the puzzle mysteries of Agatha Christie retain immense global popularity even today. Further, as stated above, the plots of many hardboiled novels in fact feature complicated puzzles. Novels like Raymond Chandler’s The Lady in the Lake or Jonathan Latimer’s The Dead Don’t Care have at their hard-boiled hearts fiendishly clever puzzle plots that would have graced even the diabolically ingenious tales of Agatha Christie and Ellery Queen.

All these matters aside, Cassuto has produced a worthwhile and interesting book. The splendid cover illustration of a steely gun and a beribboned red heart tells it all: the tough and the tender often manage to co-exist in the hardboiled novel.

Although Cassuto at times over-tenderizes the tough crime tale and I am not convinced that his engagement-with-domestic-sentimentalism thesis is the master-key that unlocks the hardboiled engine room (however much it helps reveal to us Mildred Pierce), I personally found in Hard-Boiled Sentimentality many fascinating points to engage me.

Wed 1 Jun 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[11] Comments

ROUND ROBIN MURDERS:

The Floating Admiral (1931) and Double Death (1939)

by Curt J. Evans

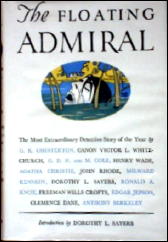

In its ongoing attempt seemingly to wring every last pound of profit out of the Agatha Christie literary estate, HarperCollins has recently reprinted The Floating Admiral, the collaborative detective novel (originally published in 1931) by fourteen members of the then recently formed Detection Club (each writing a successive chapter).

Although Agatha Christie’s contribution is a chapter of eight pages (in my 1979 Gregg Press edition) — 3% of the book — she gets top billing, with only Dorothy L. Sayers and G. K. Chesterton (the latter of whom contributed, by his own admission, a strictly ornamental prologue of five pages) also being mentioned by name, in much smaller letters. Such are the publishing perks of fame and continued books sales!

To my mind, the detective novel, requiring as it does the most scrupulous planning, is not really a form that is receptive to “round robin” treatment. Case in point: The Floating Admiral. Overloaded with complications from too many eager hands, the tale in my opinion begins to take on water and sink well before reaching its conclusion (tellingly entitled by Anthony Berkeley, “Cleaning Up the Mess”).

Nevertheless, if one is interested in authors of Golden Age detective fiction, The Floating Admiral is in many ways quite interesting, whatever its artistic failings.

Things go pretty well for the first five chapters (written by Canon Victor L. Whitechurch, G.D.H. and Margaret Cole, Henry Wade, Agatha Christie and John Rhode), with the authors refraining from over-elaboration. Unfortunately the calmly floating boat is upset by water violently churned by Milward Kennedy (his chapter, which follows Rhode’s “Inspector Rudge Begins to Form a Theory” is impertinently entitled “Inspector Rudge Thinks Better of It” — the good Inspector should not have).

Dorothy L. Sayers tries to straighten everything out that had tangled with a thirty-seven page chapter but she only makes things worse.

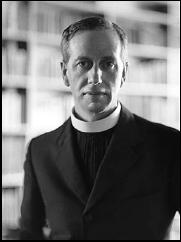

Ronald A. Knox’s chapter, “Thirty-Nine Articles of Doubt” (Chapter Eight) warningly raises thirty-nine problematical points that have accumulated for the authors following him to consider and Freeman Wills Crofts in Chapter Nine politely notes that, among other things, the body (allegedly of the admiral of course) was never adequately identified or an inquest arranged. But all to little avail.

Clemence Dane complains in her notes to her Chapter Eleven, the penultimate chapter, that the mystery has become “quite inexplicable to me” — and she likely has not been alone in that sentiment over the years.

Anthony Berkeley’s conclusion has been praised heartily by over-generous critics. I deem more like the curate’ egg — good in spots but essentially rotten. But to be fair to the poor fellow, he was handed the devil of a job.

The fun for me in reading The Floating Admiral is not in reading a cogently plotted detective novel (it simply isn’t one), but in seeing the narrative approach each author takes in his/her chapter:

â— G. K. Chesterton writes rich prose.

â— Canon Whitechurch introduces a charming vicar.

â— Henry Wade develops appealing and credible relationships among his policemen.

â— Out of the blue, Agatha Christie introduces a garrulous, gossipy lady innkeeper.

â— John Rhode discusses tidal movements (the admiral was floating after all) and sympathetically expands the role of the retired petty officer, Neddy Ware.

◠Milward Kennedy overcomplicates the story, as does Dorothy L. Sayers (the ingenious Sayers should have been given the opening chapter — she and Kennedy both clearly wanted it).

â— Ronald A. Knox makes a long list.

â— Freeman Wills Crofts checks alibis and has his inspector travel by train.

â— In his notes to his chapter, Knox amusingly declares, “I once laid it down that no Chinaman should appear in a detective story. I feel inclined to extend the rule so as to apply to residents in China. It appears that Admiral Penistone, Sir W. Denny, Walter Fitzgerald, Ware and Holland are all intimate with China, which seems overdoing it.”

In her recent Guardian review of the new edition of The Floating Admiral, Laura Wilson deems Agatha Christie proposed solution for the tale “as you would expect, the most ingenious” of all the solutions. Certainly it’s more tricksy than, say, the solution proffered by John Rhode (without a complicated murder means, Rhode is unable to play to his greatest strength here). It’s also absolutely absurd.

Here’s how Christie envisioned the state of affairs in the Admiral’s household (*** SPOILER *** to Christie’s proposed solution follows, obviously):

The Admiral’s niece is really his Uncle’s nephew masquerading as the niece. He has been doing this in his Uncle’s household for weeks, and is able to get away with it because he “has been an actor at one time” (that Golden Age crutch for the unlikely accomplishment of great disguises) and because the Admiral has not seen the niece since she was a child (he has seen the nephew more recently, however). The servants are fooled as well, as are the various beaux of the neighborhood, whom the nephew “takes an artistic pleasure” in vamping. (*** END SPOILER ***)

Ingenious or rather ridiculous? You decide for yourself, but I know what I think.

On the whole, I much preferred Double Death, a round robin novel with chapters by Dorothy L. Sayers, Freeman Wills Crofts, Valentine Williams, F. Tennyson Jesse, Anthony Armstrong and David Hume that originally appeared in the Sunday Chronicle in (I believe) 1936 and was published in book form by Victor Gollancz.

It is often stated to be a Detection Club production, but I do not see how this could be, since only two of the six writers, Sayers and Crofts, were members of the Detection Club.

In her introductory chapter to Double Death, Sayers sets up a compelling possible domestic poisoning situation, followed by a death at a railway station, at the evocatively named town of Creepe.

Freeman Wills Crofts embroiders on this opening situation ably (he even provides a stunning map of Creepe and Creepe station), as does Valentine Williams, though the latter is more known for his “Clubfoot” thrillers than his (underrated) detective novels. Unfortunately the later authors are less concerned with cluing, so that as a fair play mystery the tale ends up rather a bust (especially if you read the silly prologue, added later).

However, the writing and overall emotional situation remains compelling throughout Double Death, thus making the tale more of a success than the The Floating Admiral.

It’s interesting to note that in Double Death, written in the mid-thirties, all the authors are concerned with maintaining love interest; whereas in The Floating Admiral all the characters are sticks in whom one could not be expected take the slightest interest (well, there’s the vamping transvestite nephew, as envisioned by Christie).

As the 1930s progressed, the Golden Age detective novel began to put more emphasis on emotional situations and less on ratiocination. In the end, it is this shift in emphasis that makes Double Death more interesting than The Floating Admiral, in my view. Admiral depends for artistic success on detection and too many hands on deck sink the craft.

Yet with less than half the people involved, Double Death might have managed to work as a true fair play detective novel. Certainly Sayers, Crofts and to a lesser extent Valentine Williams made an admirable start of it.

I rather wish the novel could have been kept a collaboration simply of two: Sayers and Crofts. The two authors corresponded over the opening chapter of Double Death in the spring of 1936, with Sayers requesting and Crofts supplying pertinent points of railway station detail.

Sayers had already written her railway timetable novel The Five Red Herrings (1931) as a sort of homage to Crofts’ Sir John Magill’s Last Journey (1930) — these two brilliant books continue to stand today as the ne plus ultra of railway timetable mysteries. Double Death in their hands might well have been a classic product of the Golden Age. As it is, it is still a good read.

Wed 27 Apr 2011

ONLY IF YOU LIKE IT (THE GOLDEN AGE) ROUGH:

A REVIEW OF THE ROUGH GUIDE TO CRIME FICTION

by Curt J. Evans

BARRY FORSHAW – The Rough Guide to Crime Fiction. Rough Guides, softcover, July 2007.

The Penguin Group’s Rough Guides to literature is a smartly-presented series of pocket-sized guidebooks chock full of easily digested information on various literary genres. Barry Forshaw, who edits the Crime Time website, produced The Rough Guide to Crime Fiction [RGTCF], the series’ take on the mystery genre.

While this particular guide definitely has its virtues and can be recommended, the helpful reviewer (especially at a website like Mystery*File) must include a considerable caveat: the coverage of the Golden Age leaves quite a bit to be desired. Dare I say, it’s a bit rough?

The back of the RGTCF notes that “this insider’s book recommends over 200 classic crime novels and mystery authors.†By my count, 248 crime novels are independently listed, along with 21 authors who are specially highlighted. The first book listed was published in 1899, the last in 2007. Thus the 248 books are drawn from a time span of nearly 110 years. Here is how the nearly eleven full decades are represented:

1899-1909 3 books

1910-1919 3 books

1920-1929 4 books

1930-1939 12 books

1940-1949 14 books

1950-1959 11 books

1960-1969 10 books

1970-1979 9 books

1980-1989 16 books

1990-1999 25 books

2000-2007 141 books

Notice anything slightly out of balance here? Perhaps that 57% of the books listed come from the last decade? Or that two-thirds (67%) of the books were published after 1989? Or that 4% of the books come from the first thirty years, 1899-1929?

Barry Forshaw writes in his preface that his Rough Guide “aims to be a truly comprehensive survey, covering every major writer….It covers everything from the genre’s origins and the Golden Age to the current bestselling authors, although a larger emphasis is placed on contemporary writers.†This is a bit of an understatement, perhaps.

I would have no objection to this selective coverage, but for the fact that the book is offered as a “truly comprehensive survey†of this 109 year period. Let’s look at how the earlier decades, particularly those of the Golden Age, are covered, shall we?

First it should be noted that the listed books are divided into fifteen sections. It’s a mite confusing, since some are chronological, more or less, and some go by subject:

1. Origins

2. Golden Age

3. Hardboiled and Pulp

4. Private Eyes

5. Cops

6. Professionals

7. Amateurs

8. Psychological

9. Serial Killers

10. Criminal Protagonists

11. Gangsters

12. Class/Race/Politics

13. Espionage

14. Historicals

15. “Foreignâ€

You can see immediately how there is potential for overlap—and there often is (Hardboiled/Private Eyes). Then there are places where there isn’t any such overlap, though one would have expected it — Golden Age and Amateurs, for example.

The Golden Age was the Age of the Amateur, surely, yet the Amateurs chapter lists twenty books, only one from before 1957 (G. K. Chesterton’s The Innocence of Father Brown) and, indeed, only three (including Innocence) from before 1992.

Similarly, one might have thought that in the Historicals chapter there might have been room for Agatha Christie’s Death Comes as the End (set in ancient Egypt), John Dickson Carr’s The Devil in Velvet (set in Jacobean England), Josephine Tey’s investigative The Daughter of Time (concerning Richard III and the murder of the princes in the Tower) or one of the collections of Lilian de la Torre’s Dr. Samuel Johnson short stories; yet, no, of the 22 listed books, only three come from before 1990, and these are all between 1978 and 1985 (Ellis Peter’s A Morbid Taste for Bones, Peter Lovesey’s The False Inspector Dew and Julian Rathbone’s Lying in State).

It comes to appear that the later chapters mostly exist to provide more opportunities for listing more current authors. Indeed, one could rightly wonder, after reading this book, why the decades of the 1920s and 1930s are considered a “Golden Age†at all. The real Golden Age would seem to have dawned with the new millennium in 2000.

Only thirteen books are listed for the Golden Age:

Margery Allingham, The Tiger in the Smoke

Nicholas Blake, The Beast Must Die

Christianna Brand, Green for Danger

John Dickson Carr, The Three Coffins

Agatha Christie, Murder on the Orient Express

Edmund Crispin, Love Lies Bleeding

Erle Stanley Gardner, The Case of the Turning Tide

Patrick Hamilton, Hangover Square

Geoffrey Household, Rogue Male

Francis Iles, Malice Aforethought

Ngaio Marsh, Surfeit of Lampreys

Dorothy L. Sayers, Gaudy Night

Josephine Tey, The Franchise Affair

Again there is confusion. Is the Golden Age a period or a style? If a style, what are Hangover Square and Rogue Male doing there (couldn’t the one go in psychology, say, and the other espionage)? If a period, why do three of the books come from after the end of World War Two? Does Forshaw view the Golden Age as having lasted into the early 1950s — if so, why? It would have been nice to have some more depth here.

But, more important, Forshaw’s collection of Golden Age book listings seems ever so paltry. It will be recalled that fully 200 of the 248 listed books in RGTCF come from after the 1950s. Where are British writers like R. Austin Freeman (he’s not in Origins either), Freeman Wills Crofts, H. C. Bailey, Michael Innes, Cyril Hare and Gladys Mitchell?

And, damn it, where in hell are the bloody Americans?! It’s rather eccentric to find (if we discount John Dickson Carr) only one American, Erle Stanley Gardner — and this not for a Perry Mason but rather a 1941 Gramps Wiggins tale. In this book you will not find listings for Melville Davisson Post, Earl Derr Biggers, S.S. Van Dine, Ellery Queen, Rex Stout, Mary Roberts Rinehart or Mignon Eberhart.

One might almost conclude that the United States did not exist in the 1920s and 1930s, but for the presence of a slew of hardboiled novels by the usual suspects (Chandler, Hammett, James M. Cain, W. R. Burnett, etc.).

In a moment I found quite regrettable indeed, Forshaw writes: “The superficial ease of churning out potboilers attracted many hacks, such as the prolific but now little read Ellery Queen.†I am utterly baffled by this statement. How anyone who has read “Ellery Queen†in his best period, from the thirties to the fifties, can deem him a “hack†is beyond me (events after 1960, when the Ellery Queen name was loaned out, admittedly are more problematic).

If Forshaw thinks writing books like The Greek Coffin Mystery and Cat of Many Tails was easy, he should turn his hand to mystery writing immediately, because he must surely be a creative genius of the first order.

It’s emblematic of the low standing to which Ellery Queen has fallen that “he†could be treated in such a way. Not only were the cousins behind Ellery Queen (Frederic Dannay and Manfred Lee) great genre writers, they were most generous men who did much to promote mystery writing and genre scholarship. To me it seems rather a shame for a writer following in their footsteps to dismiss them in such a cavalier manner.

There are other omissions of which one could complain. No mention is made of Edgar Wallace and Sax Rohmer — hugely important figures in the history of the English thriller (they were even “bestsellers,†just like John Grisham, who is included here). They could easily have been fitted into the Criminal Protagonist or Gangster chapters.

Philip MacDonald is omitted, even though his brilliant Murder Gone Mad most certainly belongs among the Serial Killer tales.

Margaret Millar and Celia Fremlin are omitted in the Psychology chapter (and everywhere else, for that matter). To be sure, they are not as well-known today as Patricia Highsmith (listed for Strangers on a Train and with a separate info-box for her Ripley series), but they did fine work that influenced other writers in the 1950s though the 1970s and merited inclusion in a collection of nearly 250 books.

Julian Symons, the important and influential mid- to late-20th century crime novelist and mystery critic, is omitted as well; as are Symons’ excellent contemporaries, Michael Gilbert and Andrew Garve.

In the Origins chapter, Forshaw gives brief nods to Edgar Allan Poe, Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins, but ignores Mary Elizabeth Braddon, Mrs. Henry Wood and Anna Katharine Green. These three women are in my view inferior to the three men, but they certainly should have been mentioned at least. (They have been subjects of quite a lot of academic scholarship of late.)

Many (though not all) of the omissions I suspect can be explained by the fact that the omitted authors were out of print when Forshaw was writing his Rough Guide. And that’s perfectly fine, really, but I think this point should have been conceded up front for the benefit of the less experienced readers who presumably are the Rough Guide’s target demographic, for such innocent neophytes may be considerably misled, with potentially baneful results, in that they will not learn of many good writers or not see good writers at their best.

Ruth Rendell, for example, gets three listings, all for three novels published after 2000. I have read two of them, The Babes in the Wood and The Rottweiler, and in my view they are in no way anywhere comparable to the author’s best work from, say, 1975 to 1995. Where in the world, for example, is A Dark-Adapted Eye or A Demon in My View or A Fatal Inversion?

Similarly, P. D. James gets a listing for The Murder Room and H. R. F. Keating for Breaking and Entering, both post-1999 novels and simply not their best work. (In a separate entry for P. D. James, Forshaw lists “the top five Dalgleish books†— confusingly this list omits the one James book with a full entry, The Murder Room, while including Innocent Blood, a suspense novel in which Dalgleish never appears.)

I have probably sounded quite rough on this Rough Guide, but it does have its rough patches. Nevertheless, the book has merit, especially for people mainly interested in recent crime fiction (especially that published between 2000 and 2007), for whom I think it can be recommended without qualification. There the coverage truly does appear to be “truly comprehensive.â€

I also should mention that I particularly enjoyed the Espionage chapter and that I thought Forshaw’s treatment of Hardboiled books superior to that which he gave the Golden Age detective novel. Perhaps the Golden Age needs a Rough Guide all its own!

Thu 21 Apr 2011

PRIME TIME SUSPECTS

by TISE VAHIMAGI

Part 2.0: Evolution of the TV Genre (UK)

This section could be called the Golden Age Traditionalists. Early crime and mystery drama on television is, quite simply, divided into two strands. The British one (namely BBC), which had its roots in Radio and in the Theatre, and the American one (namely NBC), which had its roots in Radio and (in a limited capacity) in the Cinema.

British television (BBC), in the beginning, experienced something of a race in technology. Inventor John Logie Baird’s mechanical system versus EMI-Marconi’s electronic system. In February 1937, the EMI-Marconi system was formally adopted by BBC Television.

The BBC’s Royal Charter made it their duty to “inform, educate and entertain.” The first two were served with TV news broadcasts and with various instructional documentaries. The third element started off as little more than “photographed stage plays.”

It was the lofty, upper-middle-class BBC view of the time that either scenes from West End theatre productions or studio-produced adaptations of artistically intellectual novels made up almost the only “entertainment” programmes.

However, television Crime & Mystery genre history was made in 1937 — when George More O’Ferrall produced the medium’s first (hitherto unperformed) Agatha Christie play, The Wasp’s Nest, on 28 June 1937. The 25-minute TV presentation, broadcast live, starred the portly Francis L. Sullivan, a popular actor of the time who had earlier achieved a great success as Hercule Poirot in Christie’s 1931 West End stage hit Black Coffee.

The other great television genre “first” was the NBC experimental broadcast of Conan Doyle’s 1924 “The Adventure of the Three Garridebs,” transmitted from the stage of the Radio City Music Hall on 27 November 1937 as The Three Garridebs. Luis Hector played Sherlock Holmes and William Podmore was Dr. Watson.

Arriving in the latter part of the literary genre’s Golden Age, BBC presentations included television adaptations of plays by Emlyn Williams (Night Must Fall, 1937), Edgar Wallace (The Case of the Frightened Lady, On the Spot, Smoky Cell and The Ringer, all 1938), Christie (Love from a Stranger, 1938), Patrick Hamilton (Gaslight, 1939) and Edgar Allan Poe (The Tell-Tale Heart, 1939).

Of related interest was a black comedy about 19th century body snatchers Burke and Hare, and their mentor Dr. Knox, in The Anatomist (1939; presented again in 1949). The first actual UK made-for-television genre series was Telecrime (1938-39), a programme consisting of 10 and 20-minute whodunits set to test the viewer on their powers of observation and deductive reasoning.

The BBC hurriedly closed down their Television Service in September 1939 due to the outbreak of war in Europe.

Telecrimes (now plural) returned in post-World War Two 1946, written again by Miles Horton and now with James Raglan as Inspector Cameron. A similar viewer-participation series, Consider Your Verdict, was shown in 1947.

Starting in July 1946, the works of Edgar Wallace continued to be popular with The Ringer, The Green Pack (1947), On the Spot and The Case of the Frightened Lady (both 1948), and The Squeaker (1949) adapted for television.

Joining the Wallace adaptations, among others in the TV Crime & Mystery genre, were G.K. Chesterton’s play Magic (1946), the Anthony Armstrong thrillers Ten-Minute Alibi (1946), and later, in 1948, The Case of Mr. Pelham. In Gilbert Thomas’ Scotland Yard detective play Murder Rap (1946), Desmond Llewelyn played the intrepid Inspector Fearon.

Patrick Hamilton also saw plenty of small-screen time, with Rope (January 1947), featuring young Dirk Bogarde as murderer Charles Granillo, Gaslight (1947 and 1948), The Duke in Darkness (1948) and The Governess (1949).

Fans greeted Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1947) and Martin Vale’s The Two Mrs. Carrolls (1947) with glee. Agatha Christie was represented with Love From a Stranger (1947), adapted by Frank Vosper, and Three Blind Mice (1947), the latter written especially by her for BBC Television to mark Queen Mary’s birthday.

There was also a version of Maria Marten, or The Murder in the Red Barn (1947), with William Fox in the villainous Tod Slaughter role. Dorothy L. Sayers (and Miss St. Clare Byrne) had Busman’s Honeymoon (October 1947) adapted for television, with Harold Warrender as Lord Peter Wimsey and Ruth Lodge as Harriet. Toward the end of 1947, a dramatization of George du Maurier’s Trilby (October) was shown, with Abraham Sofaer as the spooky Svengali.

J. B. Priestley’s intriguing drama An Inspector Calls was dramatized in May 1948, with George Hayes as Inspector Goole (the Alastair Sim role in the famous 1954 film version). From May 1948, saturnine storyteller Algernon Blackwood told a chilling Saturday Night Story straight to camera. Anthony Holles was Inspector Hanaud in A.E.W. Mason’s At the Villa Rose (1948). On Christmas Eve 1948, the BBC presented He That Should Come, a Nativity play written by Dorothy L. Sayers.

Under the TV programme banner of Triple Bill (June 1949), Sidney Budd adapted Christie’s Witness for the Prosecution (presented alongside Denis Johnston’s Irish Rebellion play The Call to Arms and Peter Brook’s one-man [Marius Goring] show Box for One). Christie’s body-count play, then called Ten Little Niggers, was produced in August 1949.

At the end of the year, as a part of BBC’s Edgar Allan Poe Centenary (in October 1949), the TV play versions of The Cask of Amontillado, Some Words With a Mummy and The Fall of the House of Usher (all adapted by Joan Maude and Michael Warre) were presented.

Towards the end of the decade, television began adopting regular programming schedules. Emulating the long-standing BBC Radio form, strands like Children’s Television, Sport, Theatre, and Variety began producing their own series and soon established their weekly slots.

Outside of radio (where other genre authors composed works especially for BBC Radio, such as Sax Rohmer with the eight-part serial Shadow of Sumuru, December 1945-January 1946), the TV genre consisted mainly of documentaries — for example, It’s Your Money They’re After (1948), with Scotland Yard explaining some of the then-new and ingenious frauds, and The Man On the Beat (1949), showing how a policeman becomes our protector.

There was also the occasional, early drama series: The Inch Man (1951-52), concerning the adventures of a hotel house detective, and the now-legendary Sherlock Holmes (October-December 1951) series of stories starring Alan Wheatley as Holmes and Raymond Francis as Watson; the stories were adapted for television by Observer film critic C.A. Lejeune. (But more on the TV Sherlock Holmes later.)

1952 saw the beginning of the Francis Durbridge suspense thrillers, bringing UK television’s early Crime & Mystery period to a close.

In the second section of this two-part Evolution of the TV Genre, I will be looking at the same 1930s/1940s period in US television.

Note: The introduction to this series of columns by Tise Vahimagi on TV mysteries and crime shows may be found here, followed by:

Part 1: Basic Characteristics (A Swift Overview)

Tue 8 Mar 2011

Posted by Steve under

Authors[34] Comments

As posted today on Elizabeth Foxwell’s The Bunburyist blog:

The Top Ten favorite mystery writers of 1941, as reported by the New York Times on April 18, 1941, based on a survey conducted by Columbia University:

1. Dorothy L. Sayers

2. Agatha Christie

3. Arthur Conan Doyle

4. Ngaio Marsh

5. Erle Stanley Gardner

6. Rex Stout

7. Ellery Queen

8. Margery Allingham

9. Dashiell Hammett

10. Georges Simenon

Follow the link above for more information, including who was considered “Best Detective.”

Any surprises? Based on recent discussion on this blog, any comments?

Wed 9 Feb 2011

PRIME TIME SUSPECTS (Crime & Mystery Television)

by TISE VAHIMAGI

Part 1: Basic Characteristics (A Swift Overview)

It is hardly surprising, perhaps, that one of the main reasons why so little has been written about the TV crime and mystery genre is that while everyone knows what constitutes as crime drama, no one has been able to define quite what it is. As has often noted before, the general consensus is that the crime and mystery, at its core, is a puzzle.

Essentially, when not a Whodunit (identifying the criminal) it is a Whydunit (the reasons for the crime). While the puzzle factor does indeed lie at the heart of the genre, the shape and structure of the puzzle may adopt a myriad of forms.

Certain basic characteristics can be deduced from the presentations themselves. It is more often than not contemporary. It has an urban setting (the city). It involves a crime of some nature (murder and robbery being among the foremost).

But these, of course, are not the mandatory hallmarks of a TV Crime & Mystery. The Western, for instance, has lawmen and outlaws, gunfighters and hold-ups, but they are hardly crime and mystery. Although in keeping with the TV vein here, the 1870s investigations of gunfighter/private eye for-hire Shotgun Slade (syndicated, 1959-61) and the police procedurals of Denver police detective Whispering Smith (NBC, 1961) may well be the cause for some constructive argument. And not forgetting Richard Boone’s early forensics in NBC’s Hec Ramsey (1972-74).

It has been expressed before that realism rather than stylization, a sense of authenticity and not outright adventure are the keynotes. The settings, the look, the narrative, and the procedure are all intended to be realistic. Or at least plausible. Content may often appear to be ritualized and behaviour somewhat stereotyped, but the characters are (in the majority of cases, at least) individuals rather than archetypes.

In this view, the TV genre is at times variably flexible and tends to be audience-led. It often bows to contemporary flavours and fashions. Its richest moments, however, offer access to a world not normally afforded the ordinary citizen, the slightly sinister world of the dogged detective or the cynical street cop, the nocturnal prowling of the private eye or the ice-cold operation of a secret agent.

The spirit of the genre is that law and order must be maintained at all costs, or, from the flip side of the coin, outwitted, outsmarted, and even defeated.

It can take the form of the pursuit: quiet and observational (as in Maigret [BBC, 1960-63], Agatha Christie’s Poirot [ITV, 1989-93; 1995]) or physically fast and furious (The Sweeney [ITV, 1975-76; 1978], Starsky and Hutch [ABC, 1975-79]), or even the long-form (The Fugitive [ABC, 1963-67]). It can be a psychological chess game (Cracker [ITV, 1993-96]), a medical examination (Quincy ME [NBC, 1976-83]), or a forensic probe (CSI: Crime Scene Investigation [CBS, 2000-present]).

The setting can range from Miss Marple’s cozy English village of St. Mary Mead to the dangerous night-time streets of The Wire’s Baltimore. Then there’s the milieu, the occupational routine of the sleuth. Or the social and/or professional world they inhabit. The hospital/medical milieu (Diagnosis Murder [CBS, 1993-2001]). The clerical milieu (Father Dowling Mysteries [NBC, 1989; ABC, 1990-91]). Wealthy eccentrics (Burke’s Law [ABC, 1963-65]). Horse racing (The Racing Game [ITV, 1979-80]). Et cetera, et cetera…

Because it contains so many elements and facets related to crime, engaging the viewer from a variety of directions, the TV genre can not be defined precisely.

The basic story-telling characteristics are an extrapolation of the forms and formats of, in one-part, the literary genre, one-part the radio drama and one-part the cinema. The TV form (not unlike the literary form) can embrace almost any genre, and can pursue any narrative strand. It can be set in the past or in the present. It can select as its point of narrative focus the law enforcer, the criminal, or the innocent bystander. It can be a TV play, a TV film, a miniseries/limited serial, an episodic series, or a series of self-contained episodes or thematic episodes (the anthology).

The detective or sleuth character is usually the leading figure in the narrative. Leading the path that the viewer is obliged to take, they follow the pattern of the investigation. It is the sleuth’s particular application to the details of the crime that provides the dramatic interest or action (whether the gung-ho tactics of a Lt. Frank Ballinger of M Squad [NBC, 1957-60] or the careful scrutiny of a Hercule Poirot).

The sleuth may have an assistant (Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson) or a partner (Inspector Morse and Sergeant Lewis). Or may consist of the a team (Ironside [NBC, 1967-75]) or a specialised squad (the cold cases unit of Waking the Dead [BBC, 2000-present]).

The subgenre of the private detective provides, usually, the loner (Peter Gunn [NBC, 1958-60; ABC, 1960-61], Shoestring [BBC, 1979-80]). Among the subdivisions are the amateur sleuths (Hettie Bainbridge Investigates [BBC, 1996-98], Kate Loves a Mystery [NBC, 1979]) and the sleuth couple (The Thin Man [NBC, 1957-59], Hart to Hart [ABC, 1979-84], Wilde Alliance [ITV, 1978]).

They can belong to established organisations (The FBI, Scotland Yard, MI5, the CIA, the French Sûreté, Interpol) or carry out their assignments on behalf of made-up agencies (U.N.C.L.E., C.O.N.T.R.O.L., Nemesis, CI5).

The most popular, and the most associated with the TV genre, has been the police drama. Mainly the Police Detective (Columbo [NBC, 1971-77; ABC, 1989-93], Inspector Morse [ITV, 1987-2000]) but also the Police Officer (Dixon of Dock Green [BBC, 1955-76], Joe Forrester [NBC, 1975-76]).

Among the subdivisions here are the undercover cop (Wiseguy [CBS, 1987-90], Murphy’s Law [BBC, 2001-2007]), the internal affairs/investigations cop (Between the Lines [BBC, 1992-94]), as well as the mobile cop (Z Cars [BBC, 1962-78], Highway Patrol [syndicated, 1955-59], CHiPs [NBC, 1977-83]).

The Adventurer. Thrill seeker; often on the lookout for dangerous and exciting experiences. Perhaps a round-up of the expected suspects along these lines would include Roger Moore’s The Saint (ITV, 1962-69), Robert Beatty’s Bulldog Drummond (in “The Ludlow Affair” pilot [ITV, 1958] for Douglas Fairbanks Jr Presents), The Agatha Christie Hour (with “The Case of the Discontented Soldier” [ITV, 1982]), Raffles (ITV, 1977), Josephine Tey’s Brat Farrar (BBC/A&E, 1986), Modesty Blaise (pilot; ABC, 1982), The Lone Wolf (syndicated, 1954), Jason King (ITV, 1971-72), The Baron (ITV, 1966-67) and, since this type of programming seems to have the greatest appeal to casual TV viewers, the countless others that we could all name.

The Private Detective (or Private Eye) has had a long and popular run in the TV genre. In the traditional American sense (77 Sunset Strip [ABC, 1958-64] as team, The Rockford Files [NBC, 1974-80] as loner) as well as the more British tradition of the ‘consulting detective’ (The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes [ITV, 1984-85], Agatha Christie’s Partners in Crime [ITV, 1983-84]), along with the occasional UK leanings toward the American style (Public Eye [ITV, 1965-75]).