Search Results for 'Nicholas Blake'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Sat 28 Nov 2015

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

NICHOLAS KILMER – Harmony in Flesh and Black. Henry Holt, hardcover, 1995. Harper, paperback, 1995.

— Man with a Squirrel. Henry Holt, hardcover, 1996. Poisoned Pen Press, softcover, 2000.

— O Sacred Head. Henry Holt, hardcover, 1997. Poisoned Pen Press, softcover, 2000.

— Lazarus, Arise. Poisoned Pen Press, hardcover, 2001; softcover, 2005.

Go figure. In my previous review, I was more impressed by Michelle Blake’s The Book of Light than I was Nicholas Kilmer’s Dirty Linen (1999), but it’s the latter’s Fred Taylor “art mystery” series that I’ve been devouring like a box of chocolate-covered walnuts.

The situation is somewhat the same in each of the novels I’ve read: Fred Taylor, with a mysterious past that includes a traumatic stint in Vietnam, works for wealthy Boston collector Clayton Reed. Taylor has an office at Reed’s, but is part owner of a house in Watertown serving as a way station for scarred Vietnam veterans, although he lives much of the time with his librarian girl friend Molly and her two children at their Cambridge house.

The plots are generally sparked by an artwork that Reed wants Taylor to help him acquire, a task that puts Fred in extreme peril. Kilmer, a sometime painter and art dealer, has a cynical view of the art scene but he’s endowed his protagonist with a good eye for quality painting and the skill to negotiate the shark-infested waters dealers and collectors appear to swim in.

Many of the characters are only minimally sketched, but with a vitality that keeps the involved plots in motion. The most memorable of the characters is Jacob Geist, an gifted Jewish conceptual artist who is only momentarily onstage at the beginning of Lazarus, Arise. In spite of this cameo appearance, he comes to dominate the novel as Taylor discovers his secret studio and the cache of inspired drawings that he was working on when he died.

The best gimmick may be the one used in Man with a Squirrel. An antique dealer buys a section of an oil painting that has been rudely cut away from the canvas. As Fred attempts to track down the rest of the painting he finds that it and its dismemberment are connected to a popular self-help psychologist whose latest scam is deprogramming victims of satanic cults. The violence escalates, culminating in a climactic scene that strains the novel’s credibility but does tie up all the loose ends.

The action in the novels may be intense and bloody, but the dialogue is often intelligent, with informed discussions of art and artists. Some readers may find these too academic for their taste. I didn’t, but then I’m a retired academic, so maybe I’m somewhat prejudiced.

The novels don’t challenge, in precision and economy of style or structure, Iain Pears’ series set in Italy, but they are an entertaining mix of knowledgeable art dealings and crime that should interest the reader who likes the subject.

Bibliographic Note: There are three later books in the series: Madonna of the Apes (2005), A Butterfly in Flame (2010), and A Paradise for Fools (2011).

Mon 3 May 2021

REVIEWED BY MIKE TOONEY:

(Give Me That) OLD-TIME DETECTION. Autumn 2020/Winter 2021. Issue #55. Editor: Arthur Vidro. Old-Time Detection Special Interest Group of American Mensa, Ltd. 36 pages (including covers). Cover image: The Radfords’ Who Killed Dick Whittington?

As is his usual wont, in this latest edition of Old-Time Detection Arthur Vidro has once again delivered a valuable compendium of information about classic detective fiction, resurrecting long-forgotten pieces as well as showcasing up-to-date commentary about the genre.

When, in 1951, Howard Haycraft and Ellery Queen (the editor) got together to compile a list of what they considered to be a “Definitive Library of Detective-Crime-Mystery Fiction,” they probably had no idea that their compilation (commonly called the “Haycraft-Queen Cornerstones”) would still be worth consulting seventy years later. One of their choices for the list is Clayton Rawson’s locked room classic Death from a Top Hat (1938), which receives Les Blatt’s scrutiny. Another “cornerstone” is Somerset Maugham’s Ashenden (1928), which Michael Dirda, in contrast to the usual consensus opinion, does not regard as “the first modern espionage novel.”

Two now largely forgotten detective fiction novelists worth spotlighting are the married writing team of E. and M. A. Radford; they receive their due attention in Nigel Moss’s essay, which sadly notes that despite a long writing career “the U.S. market eluded them.” Moss also highlights the play, that rare theatrical bird, an honest-to-goodness whodunnit, derived from the Radfords’ sixth novel, Who Killed Dick Whittington? (1947).

While he was still living, impossible crime expert Edward D. Hoch turned his attention to Agatha Christie’s short fiction and found most of it praiseworthy: “If the short stories often are not the equal of the best of her novels, they still sparkle on occasion with her vitality and ingenuity, reminding us anew of the pleasure of a well-crafted tale.”

Dr. John Curran, the world’s foremost expert on all things Christie, has nice things to say about Mark Aldridge’s Poirot: The Greatest Detective in the World, in his opinion a “must-have book for the shelves of all fans of the little Belgian and his gifted creator.” Curran also includes little-known facts about Agatha, only a few of which yours truly was aware.

Continuing with the Christie theme is a talk by Leslie Budewitz aptly entitled “The Continued Influence of Agatha Christie”; “she was,” says Budewitz, “first and foremost a tremendous storyteller.”

Then come a couple of apposite reviews, both by Jay Strafford: Sophie Hannah’s The Killings at Kingfisher Hill (2020), starring Hercule Poirot; and Andrew Wilson’s I Saw Him Die (2020), the fourth in a series of novels making the most of that Queenian fictional trope of featuring a detective fiction writer as, well, an amateur detective.

The center piece of this issue of OTD, both figuratively and literally, is Stuart Palmer’s entertaining story “Fingerprints Don’t Lie” (1947), in which Hildegarde Withers, sans Inspector Piper, solves a knotty murder in Las Vegas.

Continuing with Charles Shibuk’s series of paperback reprints from the ’70s (at the time a noteworthy and welcome trend for classic mystery buffs), he highlights works by Nicholas Blake (Mystery*File here), Charity Blackstock (Mystery*File here), John Dickson Carr (of course!; Mystery*File here ), Agatha Christie (also of course!; Mystery*File here), Raymond Chandler (ditto; Mystery*File here), Henry Kane (Mystery*File here), Patricia Moyes (Mystery*File here), Ellery Queen (Mystery*File here), Dorothy L. Sayers (Mystery*File here), Julian Symons (Mystery*File here), Josephine Tey (Mystery*File here), and editor Francis M. Nevins’s (Mystery*File here) nonfictional The Mystery Writer’s Art, “obviously the logical successor to Howard Haycraft’s The Art of the Mystery Story (1946) . . .”

Several pages of contemporary reviews of (mostly) classic mysteries follow: Jon L. Breen about Robert Barnard’s School for Murder (1983/4) and Evan Hunter’s “factional” Lizzie (1984); Harv Tudorri about Ed Hoch’s Challenge the Impossible (2018); Ruth Ordivar about Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Angry Mourner (1951); and two reviews from Arthur Vidro about Barbara D’Amato’s The Hands of Healing Murder (1980) and John Ball’s In the Heat of the Night (1965): “with maturer re-reading, I am dazzled . . .”

The issue wraps up with letters from the readers and a befitting puzzle about Agatha Christie.

All in all, Issue 55 is definitely worth adding to your collection.

If you’d like to subscribe to Old-Time Detection:

Published three times a year: spring, summer, and autumn. – Sample copy: $6.00 in U.S.; $10.00 anywhere else. – One-year U.S.: $18.00 ($15.00 for Mensans). – One-year overseas: $40.00 (or 25 pounds sterling or 30 euros). – Payment: Checks payable to Arthur Vidro, or cash from any nation, or U.S. postage stamps or PayPal. – Mailing address: Arthur Vidro, editor, Old-Time Detection, 2 Ellery Street, Claremont, New Hampshire 03743.

Web address: vidro@myfairpoint.net

Sat 21 Dec 2019

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

CHRISTMAS AND MAYHEM:

Five Seasonal Mystery Reviews

by David Vineyard.

’Twas the night before Christmas and all through the house not a creature was stirring, not even the corpse…

Wrapping paper, ribbons, candy canes, and Christmas tree ornaments aren’t the only things that pile up around the holiday season, so do bodies, and almost from the start of the genre, the holiday of peace and love has also produced no few crimes and criminals.

Sherlock Holmes made his debut back in A Study in Scarlet in Beeton’s Christmas Annual in 1887, and crime and murder were popular themes in numerous competing Christmas Annual‘s over the years. Since books had long been a traditional gift at Christmastime, it was no surprise as the genre became more popular publishers often scheduled their bestselling mystery writers books around the holiday season hoping readers would pick up a copy of the new work for themselves and as a gift.

It was an ideal time for the genre in the Golden Age with families and friends gathered in tense stately mansions for a little mulled wine and cyanide, and the holiday often featured in classics of the genre.

Here are just a few examples over the years from classic Golden Age to modern thrillers.

NICHOLAS BLAKE – Thou Shell of Death. Nigel Strangeways #2. Collins, UK, hardcover, 1936. US title: Shell of Death. Harper, hardcover. 1936.

Nigel Strangeways is kept busy in his second outing, where he he encounters his wife Georgina for the second time, with no courting involved, and takes on a complex mystery that depends on a good use of snow and an adventurous finale.

MICHAEL INNES – Appleby’s End. John Appleby #10. Gollancz, UK, hardcover, 1945. Dodd Mead, US, hardcover, 1945.

Appleby’s End is a train station, not the finish of John Appleby, where young Detective Inspector John Appleby of Scotland Yard is deposited and becomes involved in the affairs of the Raven family in one of Innes’s best fantasmagorical outings. There are curses, pulp fiction, seeming lunacy that is eventually explained, actual lunacy no one can explain, Appleby meets and proposes to Judith Raven, the future Mrs. Appleby, while both are naked in a haystack, the wit and chuckles are genuine, the mystery good, and the end result a cross between an Ealing comedy and Agatha Christie.

Granted your taste in eccentricity may get strained, but in his tenth outing Appleby and Innes are in fine fettle for the holiday celebrations. When he wanted to no one wrote a wittier mystery than Innes. The chuckles and chortles here are deep and real.

ELLERY QUEEN – The Finishing Stroke. Ellery Queen #24. Simon & Schuster, hardcover, 1958.

From 1958, this late entry in the Queen saga is the American equivalent of the Great House mystery and incidentally a late recounting of Ellery’s first case.

Granted it is a bit hard to reconcile this Ellery with the one of The Roman Hat Mystery much less Cat of Many Tails, but there is a rhyming killer whose poesy predicts murder to follow and a case that takes Ellery his entire career to successfully solve.

Not the best of the Queen books, but nowhere near as much of a failure as some critics would have it.

DAVID WALKER – Winter of Madness. Collins, UK, hardcover, 1964. Houghton Mifflin, US, hardcover, 1964.

It’s back to Ealing, with a bit of Monty Python thrown in, as Lord Duncatto hosts a Christmas guest list at his Scottish estates that includes his beautiful and easily charmed wife and daughter, an Oxford educated son of a Mafia don, Russian spies, a mad scientist, an android, and Tyger Clyde, the idiot second best man in the British Secret Service (007 is busy) who spends more time seducing Duncatto’s wife and daughter than actually helping as all comes to a head on Duncatto’s private ski slope with a roaringly funny shoot out.

Walker is best know for his humorous novel Wee Geordie, about a naive Highlander come to London to compete in the Olympics, and Harry Black and the Tiger about the hunt for a man-eater in Post War India, both books made into films.

IAN FLEMING – On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. James Bond #11. Jonathan Cape, UK, hardcover, 1963. New American Library, US, hardcover, 1963. Film: Eon, 1969.

James Bond, 007, celebrates Christmas with a spectacular escape on skis from Ernst Stavro Blofield of SPECTRE’s Alpine HQ Piz Gloria and an encounter with Tracy, the daughter of Marc Ange Draco capo of the Union Corse, and soon to be future Mrs. Bond, foiling a plot to destroy British agriculture, and setting up a New Years Day raid to free Tracy and finally do away with Blofield and SPECTRE — almost.

It’s one of the best of the Bond books, and ended up the only Bond film to introduce a genuine Christmas song (“Do You Know How Christmas Trees Are Grownâ€).

It isn’t Christmas until James Bond throws a SPECTRE henchman into a snow blower cleaning the train tracks.

These are just a few examples of the genre celebrating Christmas in its own special way. Everyone from Sherlock Holmes to Hercule Poirot to Henry Kane’s Peter Chambers has taken on a holiday mystery. Even the 1953 film of Mickey Spillane’s first Mike Hammer mystery I, The Jury has a Christmas setting, as does the Robert Montgomery Philip Marlowe film of Lady in the Lake.

Maybe it’s because so many of us remember awaking to a special book on Christmas that we associate the genre we love with the holiday, maybe the canny Christmas release schedule of publishers, perhaps Mr. Dickens and his ghost story led us to wonder why there couldn’t be murder for the holidays if there were ghosts. Whatever the reason, the red in the holiday isn’t always from candy canes and Santa’s suit, and most of us are perfectly happy to associate a bit of mayhem with the eggnog and turkey.

Hopefully this Christmas morning will find you unwrapping a happy murder or two under your tree.

Mon 16 Sep 2019

(Give Me That) OLD-TIME DETECTION. Summer 2019. Issue #51. Editor: Arthur Vidro. Old-Time Detection Special Interest Group of American Mensa, Ltd. 36 pages (including covers). Cover image: Whodunit? Houdini?

ONCE AGAIN Arthur Vidro has brought forth a publication worth your attention, with a satisfying variety of articles about Golden Age of Detection (GAD) authors and their works, some from yesteryear and some contemporary. In case you haven’t noticed it, the GAD “renaissance” continues apace, and every issue of Old-Time Detection (OTD) serves as a fine compendium of information for both the experienced GADer (yes, it’s now a word) and the newcomer to this era of the “mystery” genre.

If you’re a Edward D. Hoch fan like us, you’ll appreciate a new series in OTD, “The Non-Fiction World of Ed Hoch,” featuring “a run of reprint pieces penned by” the latter-day master of the impossible crime short story, compiled by Dan Magnuson, Charles Shibuk, and Marvin Lachman. Hoch’s knowledge of the “mystery” field was practically unbounded, and what he had to say about it is always worth your notice.

Between the two World Wars the “mystery” story underwent a sea change from genteel drawing room bafflers to the hardboiled outlook, signaling the “death” of the formal whodunit as it was then known—or so people have been told. Jon L. Breen begs to differ; in “Whodunit? We’ll Never Tell but the Mystery Novel Is Alive and Well” he gives us just the facts, ma’am.

J. Randolph Cox focuses the Author Spotlight on Craig Rice (Georgiana Ann Randolph), known to most readers for her wild and woolly mysteries featuring lawyer John J. Malone, saloon owner Jake Justus, and Justus’s wealthy and beautiful wife Helene. Rice took the relatively understated screwball social dynamics of Hammett’s The Thin Man and pushed them to the limit: “In a genre in which death can be a game of men walking down mean streets unafraid to meet their doom,” writes Cox, “she wrote of men whose fearlessness came from a bottle—from several bottles, in fact—and made it seem comical.” However, “The drinking which she made amusing in print was not amusing in her own life.”

Thanks to a veritable explosion of paperback reprints of classic detective and mystery stories in the 1960s and ’70s, as well as the works of newer authors, the world of GAD-style fiction was kept from total extinction in the face of the hardboiled onslaught, as Charles Shibuk told us in his Armchair Detective reviews of the period.

Among the writers who enjoyed this attention from the publishers: Margery Allingham (“I’m convinced that Allingham’s best shorts are of greater value than her novels”), Eric Ambler (“The decline of this writer’s skills during the 1960s has been sad to contemplate . . .”), Nicholas Blake (“Here is another writer whose recent efforts are best left unmentioned, with one notable exception . . .”), John Dickson Carr (“This author’s best work was published between 1935 and 1938 . . .”), Agatha Christie (“If you have not read it, do not on any account miss Cards on the Table“), S. H. Courtier (“. . . obviously the logical successor to the late Arthur W. Upfield”), Amanda Cross (“. . . has only produced three novels in seven years . . .”), Andrew Garve (“. . . prolific and usually reliable . . .”), Frank Gruber, Ngaio Marsh (“Like fine wine, this author improves with age”), Stuart Palmer (“. . . his work was highly competent and always entertaining”), Ellery Queen (“. . . The Spanish Cape Mystery, which represents the last chapter in Queen’s first and best period”), Julian Symons (“Recent work has shown an attempt to return to form . . .”), Josephine Tey (“. . . I don’t think this is ultimately the stuff of which detective stories are really made”), and Raoul Whitfield (“. . . here is a rare opportunity to examine the work of an unjustly forgotten contemporary of Dashiell Hammett”).

Next, Marvin Lachman offers an affectionate memento of Lianne Carlin who, as a fanzine editor-publisher, was one of the major forces responsible for nurturing mystery fandom and keeping interest in the genre alive and well.

Dr. John Curran covers the world of Agatha Christie as no one else can: a seldom-seen and different play version of Towards Zero from 1945 (“The plot of both stage versions is, essentially, the same as the novel, as twisty a plot as any that Christie every devised”); Tony Medawar’s impending Murder She Said; The Agatha Christie Festival (“. . . in keeping with the last few years, is disappointing”); and Christie Mystery Day (“. . . no one knows what to expect until it begins”).

In “Zero Nero . . . Well, Almost”, George H. Madison offers a good summary of the finer points of Rex Stout’s popular series (46 books!) but ruefully explains why “our Nero will not be revived on screen this generation.”

As we mentioned earlier, a new feature of OTD reprises “feature articles and introductions written by Edward D. Hoch,” the first one being his preamble to the Index to Crime and Mystery Anthologies from 1990. “Here is a book,” says Hoch, “to make an addict out of any reader of short fiction.”

Amnon Kabatchnik’s summary article about Maurice Leblanc’s Arsene Lupin promises to tell us about “Lupin on Stage, the Screen, and Television,” and delivers nicely. It’s ironic that Leblanc, however, fell into the same trap that the creator of Sherlock Holmes did: “After the unexpected blockbuster popularity of Lupin, he found, as Conan Doyle had before him, that the public wanted him to produce stories and novels only about his most famous character and nothing else.”

The fiction offering in this issue is William Brittain’s “The Last Word” (EQMM, June 1968), with the author using the “James Knox” alias to signal that it won’t be one of his popular Mr. Strang adventures.

One of the best anthologies from the ’70s is Whodunit? Houdini? Thirteen Tales of Magic, Murder, Mystery (1976), which, despite its title, is not a collection of fantasy stories but mystery and detective adventures by Clayton Rawson, Rudyard Kipling, John Collier, Carter Dickson, Manuel Peyrou, Frederick Irving Anderson, Rafael Sabatini, William Irish, Walter B. Gibson, Ben Hecht, Stanley Ellin, and Erle Stanley Gardner, seasoned authors who knew how to write engrossing fiction.

Perceptive as always, in “Allure of Classic Whodunits” Michael Dirda tells us about the “distinct sense of well-being and contentment” he feels at what modern critics would regard as a defect, the artificiality that has become a “welcome attraction in many vintage who-and-howdunits,” stories which “deliberately leave out the messiness of real life, of real emotions, thus allowing the reader to mentally just amble along, mildly intrigued, feeling comfortable and even, yes, cozy,” putting the reader “a long way from deranged fantatics armed with semiautomatic weapons,” and, thus, engaging the mind rather the emotions, which is where the detective story had its beginnings (thanks, Edgar).

To wrap up this issue there are letters to the editor and a puzzle page that isn’t as easy as some. If you don’t already have a subscription to Old-Time Detection, here’s how to get one: It’s published three times a year: spring, summer, and autumn. A sample copy is $6.00 in the U.S. and $10.00 anywhere else. A one-year subscription in the U.S. is $18.00 ($15.00 for Mensans) and overseas is $40.00 (or 25 pounds sterling or 30 euros). You can pay by check; make it payable to Arthur Vidro; or you can use cash from any nation, or U.S. postage stamps, or PayPal. The mailing address: Arthur Vidro, editor, Old-Time Detection, 2 Ellery Street, Claremont, New Hampshire 03743. Arthur’s Web address is vidro@myfairpoint.net.

Fri 6 Jun 2014

RAYMOND CHANDLER’S FAVOURITE CRIME WRITERS AND CRIME NOVELS – A List by Josef Hoffmann.

In his letters and essays Chandler frequently made sharp comments about his colleagues and their literary output. He disliked and sharply criticized such famous crime writers like Eric Ambler, Nicholas Blake, W. R. Burnett, James M. Cain, John Dickson Carr, James Hadley Chase, Agatha Christie, Arthur Conan Doyle, Ngaio Marsh, Dorothy L. Sayers, Mickey Spillane, Rex Stout, S. S. Van Dine, Edgar Wallace. A lot of Chandler’s criticism was negative, but he also esteemed some writers and books. So let’s see, which these are.

A problem is that he sometimes had a mixed or even inconsistent opinion. When the positive aspects predominate the negative ones I have taken the writer or book on my list.

The list follows the alphabetical order of the names of the mystery writers. Each name is combined with (only) one source (letter, essay) for Chandler’s statement. I refer to the following books: Selected Letters of Raymond Chandler, edited by Frank MacShane, Columbia University Press 1981 (SL); Raymond Chandler Speaking, edited by Dorothy Gardiner & Kathrine Sorley Walker, University of California Press 1997 (RCS); The Raymond Chandler Papers: Selected Letters and Non-Fiction 1909 – 1959, edited by Tom Hiney & Frank MacShane, Penguin 2001 (RCP); “The Simple Art of Murder,” in: The Art of the Mystery Story, edited by Howard Haycraft, Carroll & Graf 1992.

I am rather sure that the list is not complete: It does not include all available sources nor all possible writers and books.

THE LIST:

Adams, Cleve, letter to Erle Stanley Gardner, Jan. 29, 1946 (SL)

Anderson, Edward: Thieves Like Us, letter to Hamish Hamilton, Sep. 27, 1954 (SL)

Armstrong, Charlotte: Mischief, letter to Frederic Dannay, Jul. 10, 1951 (SL)

Balchin, Nigel: The Small Back Room, letter to James Sandoe, Aug. 18, 1945 (SL)

Buchan, John: The 39 Steps, letter to James Sandoe, Dec. 28, 1949 (RCS)

Cheyney, Peter: Dark Duet, letter to James Sandoe, Oct. 14, 1949 (RCS)

Coxe, George Harmon, letter to George Harmon Coxe, Dec. 19, 1939 (SL)

Crofts, Freeman Wills, letter to Alex Barris, Apr. 16, 1949 (RCS)

Davis, Norbert, letter to Erle Stanley Gardner, Jan. 29, 1946 (SL)

Faulkner, William: Intruder in the Dust, letter to Hamish Hamilton, Nov. 11, 1949 (SL)

Fearing, Kenneth: The Big Clock, letter to Hamish Hamilton, Mar. 12, 1949 (SL); The Dagger of the Mind, The Simple Art of Murder

Fleming, Ian, letter to Ian Fleming, Apr. 11, 1956 (SL)

Freeman, R. Austin: Mr. Pottermack’s Oversight; The Stoneware Monkey; Pontifex, Son and Thorndyke, letter to James Keddie, Sep. 29, 1950 (SL)

Gardner, Erle Stanley, letter to Erle Stanley Gardner, Jan. 29, 1946 (but not as A. A. Fair, letter to George Harmon Coxe, Dec. 19, 1939) (SL)

Gault, William, letter to William Gault, Apr. 1955 (SL)

Hammett, Dashiell, The Simple Art of Murder

Henderson, Donald: Mr. Bowling Buys a Newspaper, letter to fredeeric Dannay, Jul. 10, 1951 (SL)

Holding , Elisabeth Sanxay: Net of Cobwebs, The Innocent Mrs. Duff, The Blank Wall, letter to Hamish Hamilton, Oct. 13, 1950 (RCS)

Hughes, Dorothy, letter to Alex Barris, Apr. 16, 1949 (RCS)

Irish, William (Cornell Woolrich): Phantom Lady, letter to Blanche Knopf, Oct. 22, 1942 (SL)

Krasner , William: Walk the Dark Streets, letter to Frederic Dannay, Jul. 10, 1951 (SL)

Macdonald, Philip, letter to Alex Barris, Apr. 16, 1949 (RCS)

Macdonald, John Ross: The Moving Target, letter to James Sandoe, Apr. 14, 1949 (SL)

Maugham, Somerset: Ashenden, letter to Hamish Hamilton, Dec. 4, 1949 (SL)

Millar, Margaret: Wall of Eyes, letter to Alex Barris, Apr. 16, 1949 (RCS)

Nebel, Frederick, letter to George Harmon Coxe, Dec. 19, 1939 (SL)

O’Farrell, William: Thin Edge of Violence, letter to James Sandoe, Aug. 15, 1949 (SL)

Postgate, Raymond: Verdict of Twelve, The Simple Art of Murder

Ross, James: They don’t dance much, letter to Hamish Hamilton, Sep. 27, 1954 (SL)

Sale, Richard: Lazarus No. 7, The Simple Art of Murder

Smith, Shelley: The Woman in the Sea, letter to James Sandoe, Sep. 23, 1948 (SL)

Symons, Julian: The 31st of February, letter to Frederic Dannay, Jul. 10, 1951 (SL)

Tey, Josephine: The Franchise Affair, letter to James Sandoe, Oct. 17, 1948 (RCS)

Waugh, Hillary: Last Seen Wearing, letter to Luther Nichols, Sep. 1958 (SL)

Whitfield, Raoul: letter to George Harmon Coxe, Dec. 19, 1939 (SL)

Wilde, Percival: Inquest, The Simple Art of Murder.

Fri 12 Apr 2013

NOTES ON RECENT READING: About the Mystery

by Marvin Lachman.

I really wanted to like THE POETICS OF MURDER (1983), edited by Glenn W. Most and William W. Stowe, an Edgar-nominated collection of essays from Harcourt, Brace Jovanovich in hardcover and trade paperback. Good writing about mystery is always in short supply. Unfortunately, this is an anthology of pretentious essays, written from an academic viewpoint, and boring as hell.

One essay argues that the “…intense curiosity aroused by the detective story derives from its association with the primal scene, a psychoanalytic term reference to a child’s first observation, either real or imagined, of sexual intercourse between his or her parents.” Other essays deal wih “The Detective Novel and Its Social Mission;” “Delay and the Hermenautic Sentence;” “From Semiotics to Heremneutics: Modes of Detection in Doyle and Chandler;” “Metaphysical Detective Stories in Postwar Fiction.”

An East German writer, Ernst Kaemmel, claims that the detective story is the child of capitalism, its crimes involve attacks on private property. He celebrates the absence of detective stories in Socialist countries but has missed the main reason. It is that the idea of finding truth, so essential to the detedcteive story as we know it, was not accepted in Nazi Germany, nor currently in East Germany or the USSR.

Professor David Grossvogel, reasoning along similar lines, finds the detective story bad because, by providing fictional mysteries to solve, it distracts readers from the real mysteries (and problems) of life. I wonder what, if anything, Professor Grossvogel does for escape.

In POETICS OF MURDER mysteries are repeatedly compared to “literature.” Opinions are tossed off, as if sacred, with no explanation, e,g., “Certain works are easily rejected, however. I have trouble reading Edgar Wallace and Ellery Queen, though I have tried several times.” Almost every article has a publish or perish quality to it, with never a feel for the fun in reading the mystery.

Now, if you want a really good book of essays about mystery fiction, pick Howard Haycraft’s classic THE ART OF THE MYSTERY STORY (1946), just reprinted in trade paperback by Carroll & Graf. The editor and his contributors are just as erudite and insightful, but they have written for people who read and love mysteries, and the differences show both in quality and variety.

We have serious but non-pedantic, pieces by Chesterton, Chandler, Knox, Gardner, Sandoe, Carr, and many others. There’s also humor, including Rex Stout poking his tongue in his cheek to prove that Watson was a woman. We have Edmund Wilson deriding the form, “Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd” and its proponents, writers like Nicholas Blake, Anthony Boucher, and Joseph Wood Krutch, giving a different viewpoint.

There are lists of great books, classic introductions by Sayers and Van Dine, reviews by Dashiell Hammett, etc. If ever an anthology deserved to be called “great,” THE ART OF THE MYSTERY STORY does.

However, one need not go back to 1946 to find a good book about the mystery. A fine recent book is THE CRAFT OF CRIME (1983) by John C. Carr from Houghton, Mifflin in hardcover. Carr provides interviews with twelve of the most popular mystery writers around and by adroit questioning and selection of articulae subjects, he has given us an interesting book which also increases our knowledge of the field.

The writers selected are Kendell, Lovesey, McBain, Francis,Langton, Gregory Mcdonald, Mark Smith, Robert B. Parker, Van de Watering, June Thomson, McClure, and Lathen. Mr. Carr is a good questioner with only occasional lapses when he is in too obvious awe of his subject. Otherwise, the Q and A technique works quite well, with the exception of a bias against William Faulkner which Carr betrays in several questions.

Most of the time we get probing questions which permit these writers to demonstrate how interesting and witty they are. There are differences in quality as is inevitable in a collection of this type, but not a bad interview in the lot. My favorites are those with Parker and the two women who write as as Emma Lathen.

Parker has some trenchant things to say about academic life which he was able to leave in 1979 for full-time writing. His description of his priorities in life make us feel as if we really know him, though I’m not sure about liking him. Parker provides a neat summary of the difference between old-style mysteries and the kind he writes, claiming that the world is “no longer amenable to logical deduction.”

He’s probably right in that regard, but he misses the point that it is exactly for that reason that many of us look for escape reading in which intellect does triumph. As long as writers write (and the public buys) mysteries like Parker’s which are often resolved by fist fights or gun battles, rather than by brains, we shall have a case of a self-fulfilling prophecy.

— Reprinted from The Poisoned Pen, Vol. 6, No. 2, Winter 1984/85.

Tue 11 Oct 2011

The 1980 Mystery*File AUTHORS’ RATING POLL, A to B.

I am reprinting this from Fatal Kiss #13 (May 1980), the same issue in which I reported the results of the first annual Top Ten Tec Poll.

The poll consisted of my listing ten authors whose last names began with either the letter A or B, then requesting respondees to rate them on a scale from 1 to 10. If you were not familiar with an author, then one of three categories were to have applied:

A = I never intend to read this author

B = I’d like to read this author but I haven’t yet

C = I’ve never heard of this author [or no vote]

There were 42 responses, including my own, from mystery readers scattered all over the world. Here are the results:

Author // Numerical Responses // Average // A — B — C

Eric Ambler 35 6.83 2 — 3 — 2

Nicholas Blake 26 6.65 3 — 7 — 6

Margery Allingham 32 6.00 2 — 6 — 2

Lawrence Block 23 5.89 1 — 11 — 7

Earl Derr Biggers 30 5.67 6 — 3 — 3

Charlotte Armstrong 28 5.29 5 — 6 — 3

Edgar Box 22 5.28 4 — 11 — 5

George Bagby 24 4.44 6 — 9 — 3

Edward S. Aarons 23 4.23 11 — 5 — 3

Carter Brown 24 3.79 10 — 5 — 3

One small surprise was the healthy showing of Lawrence Block, obviously not familiar to many people in 1980, but those who’d read him liked what they’d seen. [In 1980, Block had written a sizable list of paperback originals, the first three Matt Scudder books, and the first two “Burglar†novels.]

As I said at the time, I expected Ambler and Blake to do well, and they did. Aarons and Carter Brown did not do well with female voters, while Allingham and Charlotte Armstrong did not do as well with most male readers. And yes, I knew that Edgar Box was really Gore Vidal.

Since response was so high, I thought at the time that it was worth doing again. I’ll list the authors I suggested for the next poll, all of whose last names began with “C.” I don’t know if I have the issue in which the results were tabulated, or even if they ever were. I’ll have to do some searching in the garage where most of my back issues are stored.

If you’d care to record your opinions on the following authors, either in the Comments or by emailing me directly, feel free to do so:

Victor Canning, John Dickson Carr, M. E. Chaber, Raymond Chandler, Leslie Charteris, G. K. Chesterton, Agatha Christie, Manning Coles, James Hadley Chase, Tucker Coe, George Harmon Coxe, Frances Crane, John Creasey, Edmund Crispin, Freeman Wills Croft, Ursula Curtiss.

Wed 27 Apr 2011

ONLY IF YOU LIKE IT (THE GOLDEN AGE) ROUGH:

A REVIEW OF THE ROUGH GUIDE TO CRIME FICTION

by Curt J. Evans

BARRY FORSHAW – The Rough Guide to Crime Fiction. Rough Guides, softcover, July 2007.

The Penguin Group’s Rough Guides to literature is a smartly-presented series of pocket-sized guidebooks chock full of easily digested information on various literary genres. Barry Forshaw, who edits the Crime Time website, produced The Rough Guide to Crime Fiction [RGTCF], the series’ take on the mystery genre.

While this particular guide definitely has its virtues and can be recommended, the helpful reviewer (especially at a website like Mystery*File) must include a considerable caveat: the coverage of the Golden Age leaves quite a bit to be desired. Dare I say, it’s a bit rough?

The back of the RGTCF notes that “this insider’s book recommends over 200 classic crime novels and mystery authors.†By my count, 248 crime novels are independently listed, along with 21 authors who are specially highlighted. The first book listed was published in 1899, the last in 2007. Thus the 248 books are drawn from a time span of nearly 110 years. Here is how the nearly eleven full decades are represented:

1899-1909 3 books

1910-1919 3 books

1920-1929 4 books

1930-1939 12 books

1940-1949 14 books

1950-1959 11 books

1960-1969 10 books

1970-1979 9 books

1980-1989 16 books

1990-1999 25 books

2000-2007 141 books

Notice anything slightly out of balance here? Perhaps that 57% of the books listed come from the last decade? Or that two-thirds (67%) of the books were published after 1989? Or that 4% of the books come from the first thirty years, 1899-1929?

Barry Forshaw writes in his preface that his Rough Guide “aims to be a truly comprehensive survey, covering every major writer….It covers everything from the genre’s origins and the Golden Age to the current bestselling authors, although a larger emphasis is placed on contemporary writers.†This is a bit of an understatement, perhaps.

I would have no objection to this selective coverage, but for the fact that the book is offered as a “truly comprehensive survey†of this 109 year period. Let’s look at how the earlier decades, particularly those of the Golden Age, are covered, shall we?

First it should be noted that the listed books are divided into fifteen sections. It’s a mite confusing, since some are chronological, more or less, and some go by subject:

1. Origins

2. Golden Age

3. Hardboiled and Pulp

4. Private Eyes

5. Cops

6. Professionals

7. Amateurs

8. Psychological

9. Serial Killers

10. Criminal Protagonists

11. Gangsters

12. Class/Race/Politics

13. Espionage

14. Historicals

15. “Foreignâ€

You can see immediately how there is potential for overlap—and there often is (Hardboiled/Private Eyes). Then there are places where there isn’t any such overlap, though one would have expected it — Golden Age and Amateurs, for example.

The Golden Age was the Age of the Amateur, surely, yet the Amateurs chapter lists twenty books, only one from before 1957 (G. K. Chesterton’s The Innocence of Father Brown) and, indeed, only three (including Innocence) from before 1992.

Similarly, one might have thought that in the Historicals chapter there might have been room for Agatha Christie’s Death Comes as the End (set in ancient Egypt), John Dickson Carr’s The Devil in Velvet (set in Jacobean England), Josephine Tey’s investigative The Daughter of Time (concerning Richard III and the murder of the princes in the Tower) or one of the collections of Lilian de la Torre’s Dr. Samuel Johnson short stories; yet, no, of the 22 listed books, only three come from before 1990, and these are all between 1978 and 1985 (Ellis Peter’s A Morbid Taste for Bones, Peter Lovesey’s The False Inspector Dew and Julian Rathbone’s Lying in State).

It comes to appear that the later chapters mostly exist to provide more opportunities for listing more current authors. Indeed, one could rightly wonder, after reading this book, why the decades of the 1920s and 1930s are considered a “Golden Age†at all. The real Golden Age would seem to have dawned with the new millennium in 2000.

Only thirteen books are listed for the Golden Age:

Margery Allingham, The Tiger in the Smoke

Nicholas Blake, The Beast Must Die

Christianna Brand, Green for Danger

John Dickson Carr, The Three Coffins

Agatha Christie, Murder on the Orient Express

Edmund Crispin, Love Lies Bleeding

Erle Stanley Gardner, The Case of the Turning Tide

Patrick Hamilton, Hangover Square

Geoffrey Household, Rogue Male

Francis Iles, Malice Aforethought

Ngaio Marsh, Surfeit of Lampreys

Dorothy L. Sayers, Gaudy Night

Josephine Tey, The Franchise Affair

Again there is confusion. Is the Golden Age a period or a style? If a style, what are Hangover Square and Rogue Male doing there (couldn’t the one go in psychology, say, and the other espionage)? If a period, why do three of the books come from after the end of World War Two? Does Forshaw view the Golden Age as having lasted into the early 1950s — if so, why? It would have been nice to have some more depth here.

But, more important, Forshaw’s collection of Golden Age book listings seems ever so paltry. It will be recalled that fully 200 of the 248 listed books in RGTCF come from after the 1950s. Where are British writers like R. Austin Freeman (he’s not in Origins either), Freeman Wills Crofts, H. C. Bailey, Michael Innes, Cyril Hare and Gladys Mitchell?

And, damn it, where in hell are the bloody Americans?! It’s rather eccentric to find (if we discount John Dickson Carr) only one American, Erle Stanley Gardner — and this not for a Perry Mason but rather a 1941 Gramps Wiggins tale. In this book you will not find listings for Melville Davisson Post, Earl Derr Biggers, S.S. Van Dine, Ellery Queen, Rex Stout, Mary Roberts Rinehart or Mignon Eberhart.

One might almost conclude that the United States did not exist in the 1920s and 1930s, but for the presence of a slew of hardboiled novels by the usual suspects (Chandler, Hammett, James M. Cain, W. R. Burnett, etc.).

In a moment I found quite regrettable indeed, Forshaw writes: “The superficial ease of churning out potboilers attracted many hacks, such as the prolific but now little read Ellery Queen.†I am utterly baffled by this statement. How anyone who has read “Ellery Queen†in his best period, from the thirties to the fifties, can deem him a “hack†is beyond me (events after 1960, when the Ellery Queen name was loaned out, admittedly are more problematic).

If Forshaw thinks writing books like The Greek Coffin Mystery and Cat of Many Tails was easy, he should turn his hand to mystery writing immediately, because he must surely be a creative genius of the first order.

It’s emblematic of the low standing to which Ellery Queen has fallen that “he†could be treated in such a way. Not only were the cousins behind Ellery Queen (Frederic Dannay and Manfred Lee) great genre writers, they were most generous men who did much to promote mystery writing and genre scholarship. To me it seems rather a shame for a writer following in their footsteps to dismiss them in such a cavalier manner.

There are other omissions of which one could complain. No mention is made of Edgar Wallace and Sax Rohmer — hugely important figures in the history of the English thriller (they were even “bestsellers,†just like John Grisham, who is included here). They could easily have been fitted into the Criminal Protagonist or Gangster chapters.

Philip MacDonald is omitted, even though his brilliant Murder Gone Mad most certainly belongs among the Serial Killer tales.

Margaret Millar and Celia Fremlin are omitted in the Psychology chapter (and everywhere else, for that matter). To be sure, they are not as well-known today as Patricia Highsmith (listed for Strangers on a Train and with a separate info-box for her Ripley series), but they did fine work that influenced other writers in the 1950s though the 1970s and merited inclusion in a collection of nearly 250 books.

Julian Symons, the important and influential mid- to late-20th century crime novelist and mystery critic, is omitted as well; as are Symons’ excellent contemporaries, Michael Gilbert and Andrew Garve.

In the Origins chapter, Forshaw gives brief nods to Edgar Allan Poe, Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins, but ignores Mary Elizabeth Braddon, Mrs. Henry Wood and Anna Katharine Green. These three women are in my view inferior to the three men, but they certainly should have been mentioned at least. (They have been subjects of quite a lot of academic scholarship of late.)

Many (though not all) of the omissions I suspect can be explained by the fact that the omitted authors were out of print when Forshaw was writing his Rough Guide. And that’s perfectly fine, really, but I think this point should have been conceded up front for the benefit of the less experienced readers who presumably are the Rough Guide’s target demographic, for such innocent neophytes may be considerably misled, with potentially baneful results, in that they will not learn of many good writers or not see good writers at their best.

Ruth Rendell, for example, gets three listings, all for three novels published after 2000. I have read two of them, The Babes in the Wood and The Rottweiler, and in my view they are in no way anywhere comparable to the author’s best work from, say, 1975 to 1995. Where in the world, for example, is A Dark-Adapted Eye or A Demon in My View or A Fatal Inversion?

Similarly, P. D. James gets a listing for The Murder Room and H. R. F. Keating for Breaking and Entering, both post-1999 novels and simply not their best work. (In a separate entry for P. D. James, Forshaw lists “the top five Dalgleish books†— confusingly this list omits the one James book with a full entry, The Murder Room, while including Innocent Blood, a suspense novel in which Dalgleish never appears.)

I have probably sounded quite rough on this Rough Guide, but it does have its rough patches. Nevertheless, the book has merit, especially for people mainly interested in recent crime fiction (especially that published between 2000 and 2007), for whom I think it can be recommended without qualification. There the coverage truly does appear to be “truly comprehensive.â€

I also should mention that I particularly enjoyed the Espionage chapter and that I thought Forshaw’s treatment of Hardboiled books superior to that which he gave the Golden Age detective novel. Perhaps the Golden Age needs a Rough Guide all its own!

Fri 10 Dec 2010

REVIEWED BY CURT J. EVANS:

RONALD KNOX – Still Dead. Hodder & Stoughton, UK, hardcover, 1934, Pan #223, UK, paperback, 1952. US edition: E. P. Dutton, hardcover, 1934.

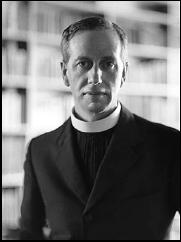

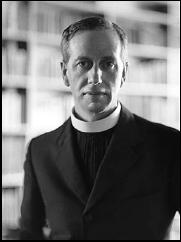

Ronald Arbuthnott Knox typifies many British writers and readers of detective fiction in that period between the World Wars we call the Golden Age of detective fiction.

Although in her recent short genre survey, Talking About Detective Fiction (2009), mystery doyenne P. D. James has written that it was Dorothy L. Sayers in the middle 1930s who made detective fiction intellectually respectable (with such “manners” crime novels as The Nine Tailors and Gaudy Night), in fact intellectuals were attracted, both as readers and writers, to detective tales at the very beginning of the Golden Age (roughly 1920), because of those tales’ ratiocinative appeal as puzzles.

For these individuals, the intellectual appeal of detective novels lay in the quality of their puzzles, not in any attempts on the part of their authors to ape the mainstream “straight” novel with compelling portrayals of social manners and/or emotional conflicts. Indeed, too much emphasis on such purely literary elements initially was often seen by common readers and more lofty genre theorists alike as detrimental in detective novels, because such an emphasis distracted readers’ minds from cold analyses of clues in their attempts to solve mystery puzzles.

One of the major literary standard-bearers for this now obsolescent view of the detective novel was an undoubtedly intellectual mystery fan and mystery writer, Ronald Knox.

Knox, a son of the Bishop of Manchester and an Eton and Oxford educated classical scholar who converted to Catholicism in 1917 (soon becoming a priest and one of England’s most prominent and articulate Anglo-Catholics), published his first detective novel, The Viaduct Murder in 1925.

Two more detective novels appeared in the 1920s (The Three Taps, 1927, and The Footsteps at the Lock, 1928), as well as Knox’s famous Detective Fiction Decalogue, wherein he laid down rules for the writing of detective fiction (all of which emphasized the puzzle aspect, or “fair play”).

On the strength of these accomplishments, Father Knox was invited in 1930 to become a founding member of the Detection Club. Three more detective novels would follow — The Body in the Silo (1933), Still Dead (1934) and Double Cross Purposes (1937) — before Knox gave himself completely over to his religious scholarship.

Less donnishly facetious than the 1920s tales, The Body in the Silo and Still Dead are commonly considered to be Father Know’s best detective novels, though oddly, they are two of the most difficult to find.

(AbeBooks lists the following number of copies for each Knox mystery title: Viaduct Murder, 27; Three Taps, 20; Footsteps, 35; Silo, 7 — all in German or French; Still Dead, 17 — though 12 of these are Pan paperback editions ranging from thirty to fifty dollars; Double Cross Purposes, 12.)

Both novels are worth reading for fans of the pure puzzle sort of detective novel, having rigorously fair play problems that even include numbered footnotes giving the pages where clues were earlier given. My preference goes to Still Dead, for its Scottish setting, over Silo, with its more hackneyed (but perennially popular) country house locale, though admittedly this is a purely literary consideration.

Still Dead concerns the death of Colin Reiver, the thoroughly undesirable heir to the Dorn estate in Scotland. Colin’s dead body was glimpsed by one of the estate’s employees, but had disappeared by the time he had left for help and returned to the spot with others.

Two days later, however, the body reappears at the same spot (still dead, hence the title). Colin is pronounced to have died from exposure, but is that really true and, either way, why were morbid shenanigans played with the corpse?

If Colin was murdered, there is no shortage of suspects. There is another employee, a gardener, whose child was run down by a drunken Colin (the latter was exonerated in court on the strength of false testimony from an Oxford friend). There are several family members, including Colin’s own father, Donald, as well as Colin’s sister, brother-in-law and cousin (truly, nobody liked Colin). There’s a family physician and also a leader of an odd religious sect to which Donald Reiver adheres.

The police write off the case (all to the good, since Father Knox evidently knew nothing about police procedure), but insurance investigator Miles Bredon (Knox’s series detective in five novels and a single, classic, short story, “Solved by Inspection”) is called in, because the question of when Colin actually died bears directly on a crucial insurance settlement (the dissolute Colin was heavily insured in his father’s favor and the Dorn estate is sadly diminished).

Still Dead starkly reveals both Father Knox’s strengths and weaknesses as a detective novelist. Positively, the fair play cluing is exemplary and reading the solution is quite enjoyable. Negatively, human interest is minimal and the plot moves very slowly.

Aside from a gentrified old lady at a hotel, Colin Reiver’s military martinet-ish cousin and a eugenics-professing doctor, none of the characters has a semblance of interest. Even these three aforementioned characters don’t come to life as they might have, given the basic material.

To be sure, Knox provides a little lightly humorous verbal byplay, courtesy of Miles Bredon’s wife, Angela (she always seems to accompany him on his investigations, despite having a child — or children, Knox is inconsistent on this point — at home). Yet Miles and Angela are no Lord Peter and Harriet, despite having preceded them into print as a mystery genre male-female duo by three years.

I found Still Dead rather more slow-moving than novels by Freeman Wills Crofts or John Rhode from this period, because Bredon’s investigation is peripatetic. Knox’s fictional works lack the relentless narrative investigative drive we see in mystery tales by those other, “humdrum”, authors, who focus so resolutely on the problem. Nor is Knox’s problem itself, though well-clued, as interesting as the alibi and murder means conundra presented by Crofts and Rhode, respectively.

In the blurb for Still Dead, Father Knox’s English publisher, Hodder and Stoughton, called Knox “a master of the English language.” Indeed, Knox is a very good writer; yet his strength as a writer is that of an essayist, not a novelist. Scattered throughout Still Dead are some fine scenic descriptions, pithy observations on religion and interesting digressions on the fate of England’s aristocracy, the nature of English gardens, chess, books, caves, hotel, etc., but, while they are interesting in themselves, by themselves they do not sustain the dramatic situation desirable in a crime novel.

Of course Knox would counter that he was merely trying to provide readers with a good puzzle, and this is a perfectly reasonable point. Admittedly, Still Dead is a good puzzle. Yet the basic material here — a dissolute gentry heir having killed a young child while driving inebriated — is interesting enough to have deserved a more serious treatment.

Knox’s handling of the material is too much on the dry side, even in the final chapter when the philosophical implications of the problem are discussed by the characters (though this is a good discussion).

Indeed, just a few years later Nicholas Blake (the pen name of poet Cecil Day-Lewis) took a rather similar plot and injected it with real human pain and suffering, in The Beast Must Die (1938), a tale much better-remembered today than Still Dead.

Even Agatha Christie, one feels, would have made a more compelling tale of Still Dead. There seems to me to have been an evident reluctance on the part of Father Knox to grapple with deeper emotions in his detective novels. (One sees this quirk as well in the half-dozen mild mystery tales by a Knox contemporary, Anglican minister Victor Whitechurch.)

Despite these reservations on my part, Still Dead is well worth reading for admirers of classical British mystery. If you can find a hardcover copy (as least this is true of the British edition by Hodder and Stoughton), you also will find a beautiful endpaper drawing of the Dorn estate and a dramatic frontispiece of stark Dorn House, both by Bip Pares, as well as that footnoted clue page guide.

The Pan paperback editions of Still Dead from 1952 that booksellers want thirty to eighty dollars for lack these graces, so charmingly redolent of the Golden Age detective novel, when many writers in their mystery tales unashamedly emphasized puzzles.

Editorial Comment: In my review of Knox’s The Three Taps earlier on this blog, I included his list of the “Ten Commandments for Detective Fiction,” also referred to by Curt.

Sun 17 Oct 2010

Dan Stumpf’s recent review of Spin the Glass Web serendipitously uncovered the fact that it was published by Harper in hardcover as a sealed mystery, in which the final chapters were sealed with a paper flap. The gimmick was that if you brought it back to wherever you bought it with the seal still intact, you could get your purchase price fully refunded.

This was nothing new. Back in the 1920s and 30s the same publisher published a full line of these books, designated as Harper Sealed Mysteries, and Victor Berch recently completed a full checklist of these.

The official series ended in 1934, but some research on the part of Victor and myself, plus some input from Bill Pronzini, has uncovered a few more books for which Harper used the same promotional idea.

There may be others, but this list should contain most of them:

JOHN DICKSON CARR Death Turns the Table, 1941.

BILL S. BALLINGER Portrait in Smoke, 1950.

MAX EHRLICH, Spin the Glass Web, 1952.

BILL S. BALLINGER The Tooth and the Nail, 1955.

NICHOLAS BLAKE A Penknife in My Heart, 1958.

NICOLAS FREELING Question of Loyalty, 1963.