Search Results for 'Q. Patrick'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Fri 23 Dec 2022

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

REVIEWED BY DOUG GREENE:

Q. PATRICK – Death Goes to School. Smith & Haas, hardcover, 1936. Banner Mysteries #2, digest-sized paperback, April 1945.

Anthony Boucher once mentioned in a letter to John Dickson Carr that it was the authors using the pseudonyms of Q. Patrick, Patrick Quentin, and Jonathan Stagge, who developed a certain gimmick in mystery writing: their books during the 193Os challenge the reader to discover not only who is the murderer but also who is the detective.

Often, but not always, the narrator is the detective; sometimes the police detective discovers the criminal; occasionally the amateur detective actually, turns out to be the murderer. Even a relatively minor Q. Patrick work like Death Goes to School plays with the reader, and not till the end do we discover who solves the crime.

The story takes place in an English boarding-school, two of whose students are murdered apparently because their father, an American judge, has passed sentences against some Nazis. I describe the story as minor because the focus is not always clear and because the surprise ending can be predicted by readers who know Patrick’s tricks.

But there is much to praise in it, especially the character of St. John Lucas, a schoolboy who (having read Chums and other sensational papers for adolescents) helps unearth evidence. But I like Patrick/Quentin/Stagge so much that even when I can see through their tricks I enjoy their work. Indeed, I am beginning to revel in predicting their gimmicks.

In short, I recommend Death Goes to School for those who haven’t read enough Patrick to predict the solution, and for those who have reached the point that they positively enjoy outguessing the author.

– Reprinted from The Poisoned Pen, Volume 4, Number 4 (August 1981).

Mon 31 Jul 2017

Hi Steve

Martha Mott Kelley (sometimes misspelt Kelly) was an early co-author of Richard Webb Wilson writing as Q. Patrick, for Cottage Sinister (1931) and Murder at the Women’s City Club (1932; published in the UK as Death in the Dovecote). Searching on the internet, little seems to be known about her except she was born New York in 1906 (a date confirmed in records) while her date of death is often said to be 2005.

I can now confirm that that date of death is incorrect. On Ancestry, there is a section for ‘US Consular reports of births 1910-1945’ which has a form dated London May 3 1937 for the birth of Sarah Mott Wilson, daughter of Martha Mott Wilson, nee Kelley, born 30 April 1906 in New York, and Stephen Shipley Wilson aged 32 who were married in Amersham, Buckinghamshire, April 26 1933. They were then living at Villas on the Heath, London.

Unfortunately the GRO Death registration has made a typo of her middle name, though it would be found by searching for Martha Wilson and her date of birth, listing her as Martha Matt Wilson. And a search of the (UK) Probate Index finds a Martha Mott Wilson of 3 Willow Rd, London who died 17 November 1989.

All this can be found by diligent searching on Ancestry etc. Most of the records with incorrect date of death of 2005 give no indication of her marriage. In fact very little seems to be known about her according to the Internet. So I hope this will help to at least fill a couple of gaps in our knowledge of her. Perhaps the lack of information about her marriage to Stephen Wilson has caused some guesswork about her death. Does anyone know the origins/source of her supposedly dying in 2005, or even 1998 as the odd website says?

Incidentally, Stephen Shipley Wilson was born 4 August 1904 in Birkenhead, Cheshire and died 16 September 1989 (living 3 Willow Rd, London). He worked for the Public Record Office and Ministry of Transport, becoming Keeper of the PRO 1960-1966 when he retired.

Tue 7 Jun 2016

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

Q. PATRICK – S. S. Murder. Farrar & Rinehart, hardcover, 1933. Popular Library #23, paperback, no date stated (1944).

Another recuperative holiday here: After having her appendix removed, Mary Llewellyn, journalist, is taking a cruise on the S. S. Moderna — a luxury liner, according to the publishers; not so luxurious, according to Llewellyn — bound for Rio.

Soon Llewellyn begins to think of the ship as the S. S. Murder since during a relatively blameless game of bridge a seemingly harmless businessman is given strychnine in a drink and dies. Shortly thereafter someone tosses another passenger from the ship during a storm.

Llewellyn’s presence in the card room at the time of the death is helpful to the investigation. As one who occasionally fills in for the bridge columnist of her paper, she transcribes two hands that lead to revealing the identity of the murderer, a Mr. Robinson who appears to have been aboard the ship only for that card game since he cannot be found after a thorough search. Yet he shows up again, this time seeking Llewellyn’s journal, which seems to contain another clue damaging to him. I have my doubts about this clue, as interpreted by a Cockney detective who is on the ship to foil card sharps.

The novel is one of the rare documentary types, in the form of letters from Llewellyn to her betrothed. Thus the style is somewhat gushy. But nothing, let me hasten to add, likely to bring a blush to the cheek of a delicately nurtured male. Good characters, good crimes, though the second is rather theatrical, and fairish play.

Bibliographic Notes: In this case the Q. Patrick byline was the pseudonymous collaboration of Richard Wilson Webb and Mary Louise Aswell. The only other novel by this pair-up was The Grindle Nightmare (Hartney, 1935). See also Comment #1.

[UPDATE.] I first posted this review last Friday, but today I noticed that I’d omitted the last paragraph, tucked neatly away on a following page. Here now, at long last, is Bill’s review in its entirety.

Wed 25 Apr 2012

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

Q. PATRICK – Cottage Sinister. Roland Swain Co., hardcover, 1931. Popular Library #386, paperback, 1951.

In the village of Crosby-Stourton in a charming cottage called Lady’s Bower lives Mrs. Lubbock with one of her daughters, a nurse. Two other daughters are visiting and die of hyoscine poisoning. A fair number of people had the opportunity, several had the means, but a motive is difficult to find.

Archibald Inge, better known as the Archdeacon because of his resemblance to a Hound of Heaven rather than an earthly sleuth, is brought down from Scotland Yard to investigate. The Archdeacon is “an expert at psychological crimes because he never used his imagination — an adept in motiveless murder because he firmly believed that there was no such thing.” Thus, he was adroit at solving mysteries because he never thought anything mysterious.

Two more deaths occur after the Archdeacon arrives in the village. It is obvious to him near the end of the investigation who did it. Unfortunately, he is mistaken. Still, he should have realized that the motive he attributed to the suspect was nonsensical.

A well-written and amusing mystery, though the clues leave something to be desired. The Archdeacon is a fascinating character.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 11, No. 1, Winter 1989.

Bibliographic Notes: The tangle of names behind the “Q. Patrick” pen name is as bad as the mess of cables hidden behind my computer. Most of the books written under that byline were by Richard Wilson Webb and Hugh Callingham Wheeler. Cottage Sinister, along with one other, was written by Webb and Martha Mott Kelley. Two other books were done by Webb in collaboration with Mary Louise Aswell.

At another time and another day, an explanation of where Patrick Quentin and Jonathan Stagge also fit into the picture would be well worth doing, but for now, I’ll let Google do what it does best. While I haven’t checked it for completeness, here is a website that comes up early in the search, is organized very well, and should prove to be helpful to anyone who’s new to the author.

Unless something has slipped by Al Hubin, this was the only appearance of Archibald Inge, the “Archdeacon.”

Fri 4 Apr 2008

Q. PATRICK – Return to the Scene.

Books, Inc.; hardcover reprint, March 1944. First edition: Simon & Schuster/Inner Sanctum, 1941. Paperback reprint: Popular Library #47, ca. 1945. Serialized previously in The American Weekly as “The Green Diary.”

I don’t know how long this website will stay up, but it presently contains loads and loads of the beautiful (if not exquisite) artwork that filled the covers of The American Weekly in its heyday. While the examples are all from 1918-1943, the magazine, a Sunday newspaper supplement for the Hearst chain, continued on through the years until the title changed to Pictorial Living in 1963, then folded for good in 1966. (Information obtained from Phil Stephensen-Payne’s magnificent Magazine Data File website.)

Which is not relevant to anything more than the fact that this novel by Q. Patrick first appeared there, nothing more, but you really ought to see those covers.

(I couldn’t resist. The one shown here is from 1941, the artist Joe Little, and as you see, one of the authors who had a story in that issue was Max Brand.)

As for Q. Patrick, there is no way I am going to try to completely untangle the web of real names that lie behind that pen name and that of Patrick Quentin (and Jonathan Stagge). Suffice it to say that Return to the Scene was the result of the primary two collaborators who used that pseudonym, Richard Wilson Webb and Hugh Callingham Wheeler. On other Q. Patrick titles, Webb had as partners, at various times, Martha Mott Kelley and Mary Louise Aswell — pairwise, mind you, not in triple tandem.

It is interesting to note that Mary Aswell’s two efforts with Webb took place in 1933 (S. S. Murder) and 1935 (The Grindle Nightmare), and her single solo effort did not appear until 1957 (Far to Go).

As for Patrick Quentin (and Jonathan Stagge), we’ll leave any discussion of who they were (and when) for another time, but as well known as practitioners of the Golden Age variety of detection, none of the various aliases, nor their books, are very well known today.

Nor of course is Quentin/Patrick alone in this category. The rise and fall in popularity of various authors over the years is a subject that is likely to come up often in these pages in the days to come. Why, for example, are Agatha Christie’s books so timeless, and Borders has nothing on the shelves by Ellery Queen or Erle Stanley Gardner, and only a handful of titles by Rex Stout? John D. MacDonald’s books may be in print, but only from Amazon. I’ve not seen them on any actual bookstore shelves, new, in quite a while.

Not that answers are likely to be very forthcoming and/or definitive, but the question at least will be something that will turn up in one of these review/commentaries every once in a while.

Case in point. Return to the Scene, by Q. Patrick. Is it a book very likely to be published today? Answer, possibly, but not by a major publisher. Maybe by a small independent publisher like the Rue Morgue Press, which specializes in reprinting classic (and obscure) mysteries from the Golden Age, of which Return to the Scene is obviously one — and if you have gotten this far into this (which eventually will turn into a review), you really should be supporting them, and if you aren’t, then shame on you — or one of those publishers that specializes in large print editions for libraries, under the obvious assumption that only older people who can’t see so well any more will have any interest in reading them any more.

It starts out like a romance novel — this is now the review — with Kay Winyard rushing to back to Bermuda to stop her niece from marrying the man she once thought she was in love with, before she discovered what kind of man he was and walked out on him. And in her purse is her weapon, a diary. A very revealing diary written by the woman who did marry him, in spite of Kay’s warning, and who subsequently killed herself because of him.

It very quickly becomes instead a murder mystery, however, and there is no surprise to learn who the victim is. The rich, the powerful Ivor Drake, who is soon also very dead. And with a huge house of possible suspects, all of whom (it is also quickly discovered) had reasons to wish him that way.

The police investigate, and for one reason or another, no one tells them the truth. Alibis are created out of happenstance and convenience. Every one has their own package of facts that they do not wish to be known, and webs of intrigue and would-be (and only reluctantly admitted) love affairs make learning the complete truth next to impossible even for Kay, who is an insider, much less Major Clifford, the ultimate outsider.

Here’s a long quote from pages 116-117. It begins with Terry talking to his sister, Elaine. Elaine is the girl whose marriage Kay came back to Bermuda to stop:

“And I’ll go on telling that story to the police. You know I’ll do everything for you. But it can’t be this way between us. I’ve got to know what you were doing tonight.” He paused and then said in a tight, husky voice: “I can’t go on like this, wondering if you killed Ivor, not being sure.”

“Killed Ivor!” Elaine have a sharp little laugh that was like a sob. “You and Kay! Why do you keep on saying that I killed him? Why would I have wanted to kill him? You don’t even know if he was murdered. It’s just Major Clifford, something crazy he said. It isn’t true. It’s all a terrible nightmare and we’re going to come out of it.”

“It isn’t a nightmare, Elaine. It’s real. And there’s no hope for us unless we tell each other the truth.”

“But what can I tell you when — when I don’t know anything?”

Brother and sister were staring at each other with a cold, desperate intensity.

Alliances are built, along with the stories the players tell the police, then collapse, and bit by bit the truth gets put together like a gigantic jigsaw puzzle. Delicious! There are clues aplenty, and the alibis so spontaneously constructed eventually cannot stand up under the pressure, and they begin to fall apart. Not one of the alibis, as it happens, is any good.

The ending is disappointing, a little, but this (it seems to me) is what almost always happens. The explanation is so mundane, so unworthy, so why-didn’t-I-think-of that, but only, you realize, in comparison to the mystery itself.

Another problem is that when the victim is so dastardly as this one is, one hates to see anyone found guilty of the crime, although of course someone must be, and in the end, all of the pieces fit together. (At least without a careful re-reading, all the way through, they do.)

Not a classic, but in the Golden Age, even the non-classics came close.

— October 2005

PostScript: A preliminary checklist of titles in the Books, Inc., line of Midnite Mysteries, of which this book is one, can be found by following the link provided.

Tue 21 Jul 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Newell Dunlap & Marcia Muller:

PATRICK QUENTIN – A Puzzle for Fools.

Simon & Schuster, US, hardcover, 1936. Victor Gollancz, UK, hc, 1936. Paperback reprints include: Pocket #83, 1940, with several later printings; Dell D192, Great Mystery Library #4, 1957; Ballantine F461, 1963; Avon PN238, 1969, with at least one later printing. Trade paperback: Penguin Classic Crime, 1986.

Patrick Quentin is a pseudonym of the collaborative team of Hugh Wheeler and Richard Wilson Webb — who also wrote as Quentin Patrick. From 1936 to 1952, the pair produced a series of successful novels featuring Peter Duluth, a former Broadway producer and recovering alcoholic, and his wife, Iris.

After 1952, Wheeler went on alone to write seven more novels under the Quentin name, four of them featuring a New York police detective, Lieutenant Timothy Trant (who also appears in novels by Wheeler and Webb under the Quentin Patrick — or, in the original editions, Q. Patrick — pseudonym).

The novels are well written and well characterized, and frequently the plots are as baffling as the pseudonyms under which they were created. The endings of these novels, be they as by Patrick Quentin or vice versa, are sure to both surprise and satisfy the fan of traditional mysteries.

A Puzzle for Fools opens in the expensive sanatorium where Peter Duluth has gone to dry out. Bad enough to be in a mental hospital, doubting your own sanity and the sanity of those about you, but what if you also begin hearing a voice whispering to you at night? And what if that voice sounds remarkably like your own? And what if that voice warns you to get away, for there will be murder?

This is Duluth’s plight. However, instead of doubting him, the director of the clinic believes every word and asks for his help in solving not only this particular puzzle but also several other strange goings-on around the clinic. Thus does Duluth become a sort of Sherlock Holmes at work in a mental institution.

Certainly Duluth, and the police, have their work cut out for them, because soon the whispering prophecy comes true and one of the staff members is murdered, only to be followed by the murder of one of the patients. This, of course, is a rich and fertile field for the whodunit, and Quentin handles it well; not only must all the patients be considered suspects, but all the staff members as well. And there are secrets to be discovered on both sides.

Other complex “puzzle” mysteries starring Peter Duluth include Puzzle for Players (1938), Puzzle for Puppets (1944), and Puzzle for Fiends (1946).

Among the novels featuring Lieutenant Timothy Trant are Death for Dear Clara (1937) and Death and the Maiden (1939), both as by Q. Patrick; and My Son, the Murderer (1954) and Family Skeletons (1965). Wheeler and Webb also wrote a series of mysteries under the pseudonym Jonathan Stagge.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright � 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Editorial Comment: For another review of this book, see the one by Marv Lachman posted here not so long ago.

Sun 19 Jul 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[8] Comments

IT’S ABOUT CRIME

by Marvin Lachman

PATRICK QUENTIN – A Puzzle for Fools.

Simon & Schuster, US, hardcover, 1936. Victor Gollancz, UK, hc, 1936. Paperback reprints include: Pocket #83, 1940, with several later printings; Dell D192, Great Mystery Library #4, 1957; Ballantine F461, 1963; Avon PN238, 1969, with at least one later printing. Trade paperback: Penguin Classic Crime, 1986.

During the nineteen-thirties many movie comedies had the hero and heroine meet “cute.” Example: Claudette Colbert and Gary Cooper meeting in a haberdashery; he only wants pajama bottoms, and she only wants pajama tops. They agree to buy a single pair.

Patrick Quentin’s A Puzzle for Fools is in that tradition, as Peter Duluth, an alcoholic theatrical producer, and Iris Pattison, a young woman suffering from melancholia, met at an exclusive mental sanatorium. This book has seldom been out of print since it was first published more than fifty years ago.

The Duluth books were to get better as time went on. This book, the first which Hugh C. Wheeler and Richard Wilson Webb wrote as Patrick Quentin, is lively and readable but shows some of the earmarks of inexperience (Wheeler was only twenty-four at the time) and hasty writing; the team was very prolific in the years before World War II.

Duluth’s fears as he goes through alcohol withdrawal while trying to solve a murder are not well conveyed. Instead, we have him saying things like, “Those were some of the most harrowing moments of my life,” but the authors do not make the readers feel it.

Too often the authors rely on Had-I-But-Known writing to get across that there are sinister events to come. For example: “Of course, I had no idea then of the fantastic and horrible things which were soon to happen in Doctor Lenz’s sanatorium. I had no means of telling just how significant these minor and seemingly pointless disturbances were.”

And, later, “Maybe I could have prevented a lot of tragedy if I had gone to the authorities there and then.” (Quentin comes close to setting a world’s record for the amount of information withheld from the police in this book.)

The pace is very quick, and Duluth’s light, self-deprecating tone makes him an enjoyable narrator. Don’t expect the kind of sophistication to be found in the British puzzles of the nineteen-thirties, though Wheeler and Webb were born in England.

No American writer has quite achieved what is to be found in Allingham, Innes, Blake, Sayers, et al. There must be an invisible barrier on the western shore of the Atlantic.

Incidentally, if the name Hugh Wheeler sounds familiar, it should. After he stopped writing mysteries in 1965 he became a major playwright, best known for his collaborations with Stephen Sondheim on such works as A Little Night Music, Pacific Overtures, and Sweeney Todd.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 9, No. 2, March/April 1987.

Editorial Comment: This is the second of two mysteries taking place in psychiatric institutions that Marv referred to in his recent review of A Mind to Murder, by P. D. James. Although the book was in print in 1987, it no longer seems to be, some 22 years later.

Coming Soon: Another review of this book by Newell Dunlap and Marcia Muller, taken from 1001 Midnights; then my review of Puzzle for Players, the second book in the series.

Also relevant: Kevin Killian’s review of The Crippled Muse (1951), by Hugh Wheeler; and two of my previously posted reviews. First, Death My Darling Daughters, by Jonathan Stagge; then Return to the Scene, by Q. Patrick.

Sat 3 Jan 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews1 Comment

REVIEWED BY KEVIN KILLIAN:

HUGH WHEELER (PATRICK QUENTIN) – The Crippled Muse.

Rupert Hart-Davis, UK, hardcover, 1951. Rinehart & Co., US, hc, 1952.

The Crippled Muse was something of a departure for Hugh Wheeler (1912-1987) then half of the writing team that wrote the Patrick Quentin detective novels featuring Peter and Iris Duluth, and the Dr. Westlake books written as if by “Jonathan Stagge.” Both series were, ha ha, petering out when Wheeler published this novel, the only one he published under his real name.

The story takes place during a few spring days in a decadent, postwar Capri, the resort island in the Gulf of Naples, and is told from the point of view of a young American academic new to international travel and the ways of the jet set.

The novel is a sort of cross between a social satire like Norman Douglas’ notorious 1917 roman a clef about Capri (South Wind), and a regular Peter Duluth novel. This one could easily have been retrofitted for the Duluths and called Puzzle for Poets.

Our hero Horace Beddoes is on sabbatical from a provincial US college in order to write the biography of an acclaimed US modernist poet. Merape Sloane has been living in seclusion in the Villa Lorliz on Capri for thirty years and will see no one, not even the most famous of fans — Aldous Huxley, Auden and even T S Eliot have all come to get at her door, and she has sent them sternly away.

And yet Horace is hoping and praying for an interview in order to complete his book. Wheeler’s great accomplishment here is the creation of Merape Sloane, so convincing as an American legend that even the snatches of her poetry quoted in passing have the authentic ring of modernism.

She is part H.D., apparently, part Mina Loy, part Edith Sitwell, part Emily Dickinson, part Martha Graham even, and embodies the weirder and most melodramatic parts of each one’s life. And yet why has she written almost nothing since an accident crippled her thirty years ago? And what was the exact nature of that accident?

Trying to get closer to Merape Sloane means Beddoes must penetrate through many layers of the demi-monde surrounding the recluse.

Those of you familiar with the 1970 Harold Prince film Something for Everyone (screenplay by Hugh Wheeler) will recognize some of the antecedents for that witty and sardonic script here, in its unsavory yet scintillating Europeans, its continual contrast between the local color of the indigenous peasants and the riffraff of the aristocracy.

When hardboiled, heavy-drinking Mike McDermott, a rival to Horace both in biography and in love, meets with a sudden, violent death, the game becomes more dangerous, and Horace comes under suspicion of having bumped his rival off.

Wheeler invokes Capri in a flurry of impressionistic gestures: “…this island of wild humps and sudden plunges, this sharp, pinnacled fantasy of rock, grey as a dove’s breast, and below, always dizzily below, the Mediterranean, flashing with the blueness of all the butterfly-wings in Brazil.”

Merape Sloane’s life proves itself an ironic allegory for the nature of poetry itself, and her strange progress from a Cold Comfort Farm-like life of abject rural poverty, to being the venerated object of a cult of aesthetes, bisexuals and millionaires, has the ring of something really thought out, really felt.

As a mystery novel, The Crippled Muse is fairly clued, but Wheeler is so skillful that the last forty or fifty pages produce one amazing revelation after another.

_____

Happy new year everyone! My new year’s wish is still to get my paws on a copy of the elusive Danger Next Door by Q. Patrick (1952). Any leads tragically appreciated!

Sat 7 Oct 2017

BRAM STOKER – Dracula’s Guest. Published posthumously in the collection Dracula’s Guest and Other Weird Stories (George Routledge & Sons, UK, hardcover, 1914). Reprinted many times including: Weird Tales, December 1927; The Ghouls, edited by Peter Haining (W. H. Allen, UK, hardcover, 1971; Pocket, US, paperback, April 1971); Dracula’s Guest and Other Stories, edited by Victor Ghidalia (Xerox, US, paperback, 1972); Werewolf!, edited by Bill Pronzini (Arbor House, US, hardcover, 1979); The Vampire Archives: The Most Complete Volume of Vampire Tales Ever Published, edited by Otto Penzler (Vintage Crime/Black Lizard / Vintage Books, softcover, 2009); The Big Book of Rogues and Villains, edited by Otto Penzler (Vintage Crime/Black Lizard, softcover, October 24 2017). Film: Among others “inspired” by the story, Universal’s film Dracula’s Daughter (1936) was supposedly based on the tale, but nothing of the plot was used.

It is generally stated and accepted that this story, somewhat complete in itself, was the the first chapter of the original manuscript of Dracula, but deleted for reasons of length. It is told by an unknown narrator, but presumably it was Jonathan Harker who very foolishly ignores the advice of his innkeeper and the coachman of his carriage to get out to investigate on foot a village said to be unholy and abandoned for some 300 years.

On Walpurgis Night, no less. Needless to say, he soon realizes that he has made a dangerous mistake. Some thoughts. First of all, how modern Stoker’s writing is. This is story that could easily pass as having been written last week, if not yesterday. Secondly, it is wonder how well this story anticipates all those Hammer horror films that came along so many years later.

BONUS:

Here are the stories included in the Rogues and Villains anthology:

THE VICTORIANS

At the Edge of the Crater by L. T. Meade & Robert Eustace

The Episode of the Mexican Seer by Grant Allen

The Body Snatcher by Robert Louis Stevenson

Dracula’s Guest by Bram Stoker

The Narrative of Mr. James Rigby by Arthur Morrison

The Ides of March by E. W. Hornung

19TH CENTURY AMERICANS

The Story of a Young Robber by Washington Irving

Moon-Face by Jack London

The Shadow of Quong Lung by C. W. Doyle

THE EDWARDIANS

The Fire of London by Arnold Bennett

Madame Sara by L. T. Meade & Robert Eustace

The Affair of the Man Who Called Himself Hamilton Cleek by Thomas W. Hanshew

The Mysterious Railway Passenger by Maurice Leblan

An Unposted Letter by Newton MacTavish

The Adventure of “The Brain†by Bertram Atkey

The Kailyard Novel by Clifford Ashdown

The Parole of Gevil-Hay by K. & Hesketh Prichard

The Hammerspond Park Burglary by H. G. Wells

The Zayat Kiss by Sax Rohmer

EARLY 20TH CENTURY AMERICANS

The Infallible Godahl by Frederick Irving Anderson

The Caballero’s Way by O. Henry

Conscience in Art by O. Henry

The Unpublishable Memoirs by A. S. W. Rosenbach

The Universal Covered Carpet Tack Company by George Randolph Chester

Boston Blackie’s Code by Jack Boyle

The Gray Seal by Frank L. Packard

The Dignity of Honest Labor by Percival Pollard

The Eyes of the Countess Gerda by May Edginton

The Willow Walk by Sinclair Lewis

A Retrieved Reformation by O. Henry

BETWEEN THE WORLD WARS

The Burglar by John Russell

Portrait of a Murderer by Q. Patrick

Karmesin and the Big Flea by Gerald Kersh

The Very Raffles-Like Episode of Castor and Pollux, Diamonds De Luxe by Harry Stephen Keeler

The Most Dangerous Game by Richard Connell

Four Square Jane by Edgar Wallace

A Fortune in Tin by Edgar Wallace

The Genuine Old Master by David Durham

The Colonel Gives a Party by Everett Rhodes Castle

Footsteps of Fear by Vincent Starrett

The Signed Masterpieces by Frederick Irving Anderson

The Hands of Mr. Ottermole by Thomas Burke

“His Lady†to the Rescue by Bruce Graeme

On Getting an Introduction by Edgar Wallace

The 15 Murderers by Ben Hecht

The Damsel in Distress by Leslie Charteris

THE PULP ERA

After-Dinner Story by William Irish

The Mystery of the Golden Skull by Donald E. Keyhoe

We Are All Dead by Bruno Fischer

Horror Insured by Paul Ernst

A Shock for the Countess by C. S. Montanye

A Shabby Millionaire by Christopher B. Booth

Crimson Shackles by Frederick C. Davis

The Adventure of the Voodoo Moon by Eugene Thomas

The Copper Bowl by George Fielding Eliot

POST-WORLD WAR 2

The Cat-Woman by Erle Stanley Gardner

The Kid Stacks a Deck by Erle Stanley Gardner

The Theft from the Empty Room by Edward D. Hoch

The Shill by Stephen Marlowe

The Dr. Sherrock Commission by Frank McAuliffe

In Round Figures by Erle Stanley Gardner

The Racket Buster by Erle Stanley Gardner

Sweet Music by Robert L. Fish

THE MODERNS

The Ehrengraf Experience by Lawrence Block

Quarry’s Luck by Max Allan Collins

The Partnership by David Morrell

Blackburn Sins by Bradley Denton

The Black Spot by Loren D. Estleman

Car Trouble by Jas A. Petrin

Keller on the Spot by Lawrence Block

Boudin Noir by R. T. Lawton

Like a Thief in the Night by Lawrence Block

Too Many Crooks by Donald E. Westlake

Sat 20 May 2017

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

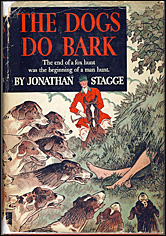

JONATHAN STAGGE – The Dogs Do Bark. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1937. Popular Library #350, paperback, 1951. Also published as Murder Gone To Earth (Joseph, UK, hardcover, 1936).

A question is often raised about whether it is worthwhile to spend time and space reviewing a poor novel. Why bother? Well, if nothing else, to warn prospective readers that they may be in for a disappointment. And a disappointment is what The Dogs Do Bark definitely is in this reviewer’s opinion.

Here ! must flout our distinguished editor’s admonition not to give anything away in a review. How else describe this book’s weaknesses?

A headless and armless female body is found during a fox hunt in Massachusetts. Since a female is missing from the area, her father, a religious fanatic, is asked to view the presumably naked torso of the corpse and identifies it, more or less, as his daughter, while throwing in some wild religious quotations to prove his fanaticism. Don’t ask me how this zealot was so familiar with his daughter’s naked body. (And the author certainly didn’t want anybody to ask.)

After the father has viewed the corpse and identified her, more or less, he is then read a description of the body, presumably another author’s ploy so that the authorities can say that she was not virgo intacta, although not pregnant, and thus must either have been married or immoral. The coroner and the doctor — the latter is the amateur detective in the novel — who had been deputized by the sheriff both seem to think that sexual intercourse is the only way that the hymen can be broken, no doubt a fond delusion during the 1930s.

Later on in the book we are told that the girl identified as the corpse thought she was pregnant. Do the doctor and the sheriff look at one another with wild or even mild surmise? Of course not. The primary reason for the head and arms being removed from the body does not occur to them, either. If it had — and some thought was given to another female’s disappearance, one who looked much like the corpse — the book would have ended at chapter 3 or 4. And what then would have become of the so-much-per-word story?

The arms are found in the hunting pack’s kennels, stripped to the bone by the dogs. The head is located later elsewhere, kept by the killer for reasons never made clear. The deputy doctor seems to have only one patient, a hypochondriac, so he has plenty of time to blunder around and nearly get himself killed in a had-I-but-known-or-even-given-it-some-thought fashion. He comes close to being burned to death in an old barn by the murderer, and it would have served him right. Once the corpse is correctly identified, a telegram from another police force points out the killer.

Recommended only to those who have a mild interest in the U.S. fox hunting scene.

Editorial Comment: I believe but I am not positive that the doctor Bill refers to in this review is Dr. Hugh Westlake, who appeared in all nine of Jonathan Stagge’s detective novels, of which this is the first. (I do not know who the deputy doctor might be.) Stagge was a pseudonym of Richard Wilson Webb, (1901-1970) & Hugh Callingham Wheeler, (1912-1987), who also collaborated on books as by Q. Patrick and Patrick Quentin.