Search Results for 'whodunit'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Thu 21 Feb 2013

CORNELIA PENFIELD – After the Town Clerk Died. Typed manuscript with corrections made by hand. No date. Unpublished.

Prologue: Cornelia Penfield was the author of two published works of detective fiction, both of which have recently been reviewed on this blog: After the Deacon Was Murdered and After the Widow Changed Her Mind. If you haven’t already, I’d recommend going back to read the earlier reviews (follow the links) before continuing:

The Internet is wonderful. It’s terrific. It took only a few days to trace down the family of Mrs. Cornelia Penfield Lathrop. She died in 1938, and a son Robert died several years ago, but Marilyn Lathrop, Cornelia’s daughter-in-law, is still alive and well. She lives two towns over to the east of me, and I’m not sure exactly what she thought when she opened the letter I wrote her, asking if she indeed was who I thought she was. (No, I have that wrong. I wrote the letter to Robert Lathrop, as the telephone is in his name, and I wasn’t sure if it were Robert the son, still living, or perhaps Robert, a grandson.)

In any case, she wrote back, saying yes, Cornelia was her mother-in law, and yes, she’d welcome a chance to talk to me on the phone. I called not too late the following evening, hoping to set up a time when we could talk longer. What happened instead was a conversation about Cornelia Penfield that lasted at least 30 minutes. I no longer remember whether I received the answer in the initial letter that she wrote me or in that conversation, but the question that I was simply itching to ask, given the first suitable opportunity, was “Do you know why the third book was never published?â€

What I didn’t expect, whenever it was that the question was asked, or at least not realistically, was the reply that manuscript still existed, and would I be interested in seeing it sometime? I think my mind went blank right about then, but you know what my reply had to have been.

I went to see it, had a chance to have another lengthy conversation with Marilyn Lathrop and (which I never really anticipated) I was allowed to borrow it. I have kept it far too long. There were some extenuating circumstances, including a number of unexpected events that intervened and kept me from starting to read it, but I think the real reason I put off reading it for so long was that for me, it was a once-in-a-lifetime event, and I was simply relishing the anticipation much longer than I should have.

As to the answer to the question as to why the book was rejected – and this is the family’s version of what happened – is that the publisher said it “wasn’t seamy enough.†When we get to the review proper, I’ll go into that, but later on Marilyn partially reconsidered, saying that perhaps “seamy†wasn’t the word that was used, but even if it wasn’t, it was close.

What I didn’t realize right away, though, is that the title of the manuscript I have is NOT the title of the third book that was promised, and there is nothing in the story itself to suggest the title was changed, there being no doctor in the tale that I have.

So there is a fourth novel, and it is still missing, and unless someone in the Lathrop family remembers something – a box or trunk never opened – we shall reluctantly have to assume that it no longer exists.

It also seems possible that After the Town Clerk Died is a novel that was never sent to Putnam’s. It may have been that After What the Doctor Said was the one that was rejected, with the aforesaid comment attached, and that Town Clerk was abandoned before completion, almost but never quite finished.

It is, I am sure, no longer possible to say. It is remarkable that the typed pages still exist. As a mystery, it needs some work. I’ve never tried to write a full-fledged detective novel, or even an unfledged one. Reading this, in what I’m going to continue to think of as being in the form of a rough first or second draft, gave me quite a bit of insight into the physical problems of doing so. Being sure that an event mentioned on page 233 (say) as having happened earlier on page 165, really occurred, for example, and that a clue discussed on page 198 (say) was mentioned and pointed out back on page 53.

That’s what still needs some fixing, not a lot, and editors of detective story fiction deserve all the praise we can give them. (There are still a few of them, but not as many as before.)

Jane Trimble, the semi-elderly genealogist who appeared in the two published books, also appears in this one, her primary focus being that of keeping her friend Gordon Burr from becoming a suspect in the death of a man in a suspicious fire. Burr is a writer who is not only having problems completing his latest book, but who is also having domestic troubles with his wife, and Jane cherishes them both.

I don’t imagine retelling the plot in detail makes a lot of sense, as when is anyone else ever going to be able to read this as a work of detective fiction? I’ll retract a good deal of what I was going to say, and start painting things with a wider brush.

But what I started to say still applies. Jane was hardly the detective of record in the first book at all, and it was something of a surprise to find that she appeared in the second. In the second one, Widow, she shared sleuthing duty with another character, but in this one, she is the primary detective, even to the extent that she is the one with a watchful eye out for trouble even before there is trouble to be had.

And here lies a problem. It takes nearly 150 pages before the body of the dead man is discovered, and it takes a fairly talented mystery writer to keep the reader’s interest that long, with little or no “action†taking place. There are a lot of characters to identify, a lot of refined conversation to listen in on – this is suburban Connecticut, after all, and even in (say) 1935, the level or refinement was greater than many another part of the world.

Once Jane’s detective activities begin in earnest, it is quite a complicated state of affairs the mystery finds itself in, and – here’s another problem – many of the clues happened or were discovered back in the earlier portion of the book when no one (but Jane) even suspected that they were clues. An alert reader might get glimpses of the essentials of the plot in its early going, but as the manuscript now stands, some strong rewriting seems to be very much necessary.

There is a great to-do about who was where and saw what when, and even more about beards, false beards, who had one and who shaved one off and who hired someone to impersonate them who did or did not have a beard when he needed one. I may not have implied what I wanted to in that sentence. It is all very fascinating.

Penfield’s great talent was in miniature characterization, burbling good humor, dialogue, and in the end, a kindly heart. The mystery, as in Widow, turns out to have been a minor affair, complicated by a myriad of factors, related and unrelated, but once again – with a sense of forgiveness for loose ends – it’s a charming affair that I’m glad to have had the pleasure to read. (By the way, the Town Clerk’s death is involved, but he died of natural causes, and his involvement comes only in a clever way, one that could have been known only by someone intimately involved with the problems of genealogical research, and as such, it may be a First. The entire series, in other words, and this one in particular, may be “One for the Books.â€)

Postscript: I have debated for a while whether I should do this, and once again, since you’re reading this, you will know that the better argument won. Here’s a longish quote from pages 245-246, getting within a hundred pages from the end. It will give you a sense, I think, of Cornelia Penfield’s knowledge of the conventions of the mystery field, and how, as I’ve mentioned in the two previous reviews, how she liked to play around with them.

Reviewing her evening with the Admiring Confidants, in the foggy dawn of a New York spring day, Jane felt she had not shone. How was it that fictional detectives made themselves the center of awestricken attention, summed up their findings in crisp dramatic sentences, and stated so authoritatively that the criminal must have done this and that as was clearly shown by these and those?

How was it that invariably they enlisted the kindly and obsequious services of? (1) Scotland Yard (2) the Division of Investigation of the Department of Justice (3) the Police Department of the metropolis concerned – (Select (1), (2), or (3) giving reasons for choice and write in your own words a complete detailed description of methods employed by that organization.)

By what magic did they also find various district attorneys, solicitors, barristers, photographers, experts in criminology and laboratory practice, reporters, butlers and valets to abet and assist the Super-Detective without wanting any reward beyond a kindly smile, who argued with him just sufficiently to point out his infallibility- and were content with being yes-men and filling about two hundred and ninety pages of escape literature?

None of her own intense concentration and really intelligent work on the Dymchurch affair had to date earned her a darned thing — and might possibly, as Judge Whitaker had hinted, be bringing her activities suspiciously into the official limelight.

However positive she might be that at least one of the theories so neatly worked out and counter-indexed in her notebook was a correct solution, just how was she going to submit the notebook to the Principal Official and secure his kind attention? After having, for reasons which at the time appeared to her sound, led him to believe her a romantic and muddleheaded moron?

And coming down to her own friends from whom at least she had the right to expect some awed silent admiration, what had been their attitude?

Merely a polite and passing interest in the least important phases of the whole affair – the beard and the altered entry – and in order to explain those she had had to battle against guppies and banal bunnies as conversational topics!

Worse of all, Judge Whitaker upon whom she had relied for so much of encouragement and intelligent cooperation, had not only failed her utterly, but had expressed his opinion in tactful judicial terms that she was a Meddlesome Mattie, and had better let the state of Connecticut and the town of Dymchurch deal with their own affairs as they were so well equipped and prepared to do.

“Ah well,†said Jane, ringing the pantry service. “A bit of breakfast may chirk me up. I must hold to the thought that I am not a Super-Detective, but merely riding a hobby-horse I found grazing along the roadside: and that even so I am an unpretentious Jarrocks and not eligible to the Hunt Club: nor am I called upon to demonstrate haute école before a circus audience that thinks a balotade is probably an off-color French joke… But, all the same, if this sinister Langton person does do away with me and dispose of my body in a crematory way, won’t all the grown-ups be sorry and begin to appreciate the risk I am taking?â€

The pause-giving difficulty would be that she would not be around to hear the post-mortem regrets and to see Judge Whitaker turn her notebook pages with trembling fingers or to hear him say “Poor Jane! How little we appreciated all this clever work of hers!â€

She sipped her coffee and enjoyed one of the famous St. Crispin croissants and decided to live a while longer, Langton willing. Even though a few more deaths were needed to bring the Dymchurch quota up to a good Van Dine average.

I’ve decided that if I’m going to do long quotes from the text, I ought to do it right. Here’s an earlier passage, from pages 35-38, in which Jane meets Don Wyckoff, a local attorney, who may or may not be representing either artist Jack Collins or his wife Julia in their upcoming divorce proceedings. As part of their conversation, some more light is shed on Jane’s detective proclivities:

Wyckoff smiled diplomatically. “… But I can’t undertake to nurse Jack Collins all the time.â€

“Are you representing him or Julia in the oncoming action? Or doesn’t one ask?†Phyllis nibbled a cracker.

“One doesn’t – not at this moment.â€

“But is Julia really going to carry it through, Don? I should almost think after all these years … tell the waitress no mayonnaise for me, please – just the diet dressing … I’m sorry, Don. Ethics always seem so silly among friends – professional ethics, I mean.â€

There was a slight frown on Wyckoff’s bland forehead and he addressed his next remark directly to Jane. “Judge Whitaker spoke of you as a triple A detective, Miss Trimble.â€

“I suppose he referred to the Gleason will case. That was simple genealogical research. Elementary.â€

“The name is Wyckoff, not Watson. And I know an unfortunate lot about how much ability as well as research that sort of thing takes. Being myself mostly a digger-out of facts for others to profit by.â€

“Oh, Don! Don’t be so ’umble. He’s in with the oldest, snootiest law firm in Tidewater, Jane – seven names and an ampersand on the door – and every one of the seven is a judge or a trustee or a receiver or something.â€

“Except me and the ampersand. The only way I maintain my dignity out of office-boy hours is to keep a few clients of my own over here in Dymchurch.â€

He began to outline amusingly a case involving a farmer and his step-son. Phyllis listened with applauding phrases at the right moment. Jane divided her attention between the table in the alcove – as yet unclaimed – and his bland face and pleasant voice. She had rather a prejudice against young lawyers, so given as a rule to screening their uncertainties by bumptious pronouncements and bristling authority. Wyckoff was of another sort. He had an adaptable geniality that hinted of the politician – of experience in gaining the confidence of folk of all degrees. A tactful young man, she concluded, who had been about a bit, who was sure of himself but not irritatingly so, and who might will be exactly what her beloved old neighbor, Judge Whitaker had been in his green legal youth. The anecdote finished, he again referred to Jane’s detective experience.

“It’s been rather accidental and incidental,†she said. “If I ever tried real detecting, I’m afraid I’d be much more interested in a criminal’s heredity and background and other antecedents than in the crime and whodunit. In the long run, though, I suppose detection and genealogy require about the same amount of patience and imagination and experience – and luck – â€

“The ideal job of detection may,†laughed Wyckoff, “but the detectives I’ve met in real life depend principally upon a lack of delicacy and a certain flair for installing dictaphones, breaking down doors, and otherwise intruding on the private life of a sincere criminal. Not picturesque persons – and the less imagination the better. You ought to hear our local chief of police, Hal Flint, cuss out detective story detectives. So many of the young literary colonists scribble mystery novels and they keep looking Flint up and getting in his hair and asking him questions.â€

“And I suppose he replies in the same spirit as did the doctor whose dinner-partner wanted free medical advice and asked him what he did when he had a cold – he snorted at her and said ‘Same as everybody else ma’am. I cough and sneeze’ –â€

“Exactly the way Flint feels. Routine and romance don’t team successfully. And what’s more, if your average detective has no imagination, your average criminal certainly has less. I’ve never met a master-mind, I never hope to see one – but if I do, I’ll call you in, Miss Trimble. I promise.â€

“Thank you,†said Jane solemnly. “I’ll endeavor to cope genealogically.â€

One more quote. I hope I’m not overdoing this, but I’d like to demonstrate what I mentioned earlier about Cornelia Penfield’s knack for dialogue. Jane is talking to Mrs. Turner, the cook in the Burrs’ household. Her husband Jim is the Burr’s handyman, and Beulah is their daughter, whom they’ve been concerned about. Either I’m right, or I’m hopelessly wrong, but I think this is the way people actually talk, instead of in neat diagrammable sentences. From pages 76-77:

“Perhaps I can give Mrs. Burr a few hints when she comes back,†concluded Jane. “She hasn’t, I know, the faintest idea of making it hard for you.â€

“I know she hasn’t. That’s why I’ve kep’ my mouth shut and tried to do my best. Of course I never thought I’d get to do housework for other folks, but we couldn’t have it nicer than we have here, with our own little house an’ all. And after stretchin’ an’ strainin’ so many years, it’s a real rest to spend somebody else’s money for a change … not but what I don’t try to manage just as close ’sif it was my own†– added Mrs. Turner conscientiously, “But Mr. and Mrs. Burr, they’ve never had to count every cent twice, and they both do like good victuals … if we only had Beulah back and Jim didn’t get upset so easy–â€

“About her?â€

“Yes. That’s the whole trouble. Jim kep’ straight ’s string till she went off t’ New York, but people ’round here don’t give him credit for that. An’ I was hopin’ maybe if she did come home–†Mrs. Turner’s tight lip quivered – “You see, Miss Trimble, we lived out of Branford on a farm of our own when we was first married, and all the time Beulah was growin’ up we had all our own things nice. Then the bank closed in New Haven where we had our money, and the other bank foreclosed on a moggidge Jim had taken out to buy some more proputty with, and it was before they started the Home-Owners’ Loan or anything and we couldn’t beg or borrow a cent – so we lost our place and had to sell our furniture for what it’d bring – I had real nice walnut suites that had b’longed to my folks – and the best we could do was try to live with Jim’s step-uncle over Redding-way, but he’d never liked Jim – and his second wife didn’t get along with Beulah an’ we all had it pretty hard till Beulah took a notion to take her high-school cookin’ and so on seriously and get herself a job waitin’ on tables at the Tavern. She did real well with tips an’ all an’ then she found out there’d be this place for us all so we decided we’druther be independent an’ work for pay than keep on where we were … Only with Beulah gone and no relyin’ on Jim no more, I guess the Burrs is about ready to make a change. And if we haveta leave here, Jim’ll just get from bad to worse.â€

In conclusion: Thanks again to Marilyn Lathrop for allowing me the use of the manuscript, and for the conversations we have had concerning her husband’s mother. Since Marilyn never knew her mother-in-law, her own knowledge is based on what Robert and other members of the family have told her over the years. Cornelia’s daughter Helen Harriet Petty is still living. She is in her late 80s, and the memories she has of her mother have been conveyed to me through Marilyn. A nephew, Fred Lathrop, is also still alive, and he has assisted me in proofreading the reviews and commentary above. He remembers her only as a young boy, recalling for the most part the years toward her death, when she was often bedridden with tuberculosis.

My impression of Cornelia Lathrop, through these conversations, was that she was a very progressive woman, ahead of her time in many ways. Similar in nature, I believe, to Eleanor Roosevelt, a lady whom Cornelia is said to have met. Not many women in the 1920s, for example, would take her three children to live in France for well over a year without her husband, who stayed home working.

She was always interested in the arts. Besides her brief involvement with Broadway, previously mentioned, in the mid-30s she also wrote several articles for Stage Magazine, including five in a 1936 series on famous Hollywood directors.

The photo you see at the top of this article/review is a publicity shot taken by her mystery publisher, G. P. Putnam. It’s nice to be able to display it again.

Wed 6 Feb 2013

TWELVE IMPORTANT ACADEMIC ESSAYS ON CRIME FICTION

by Josef Hoffmann

When I drew up my rcent list of the “Twelve Best Essays on Crime Fiction,” I restricted it to literary essays. This is clear from the fact that almost all the essayists on that list have also written crime stories. I am now complementing that with a list of essays by academics.

What characterises an academic essay? The knowledge presented, the content of the message, is more important than the formal beauty of the writing. It is not so much a matter of the essay providing reading pleasure, as of it stating the truth by putting forward a differentiated and critical analysis of crime fiction texts.

The theses have to be defended by means of stringent arguments and text references. The sources of the knowledge should be referred to, preferably in the form of precise data in footnotes. The author of the essay must be familiar with scholarly methods. As a rule, he or she will already have recognised status in the academic field, for example, as a university professor. An important academic essay will be cited and discussed in academic writings and act as a stimulus for other essays on the topic, etc.

In the following list I have only essays that appeared in print. For this reason an essay like “The Amateur Detective Just Won’t Do: Raymond Chandler and British Detective Fiction†published by Curtis Evans in his blog, The Passing Tramp, cannot be included. Online essays would require a list of their own.

Now to the announced list, presented alphabetically by author:

Alewyn, Richard: “The Origin of the Detective Novel†in The Poetics of Murder, ed. by Glenn W. Most and William W. Stowe, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1983.

Alewyn puts forward the provocative thesis that the detective story had its roots not in the rationalist 19th century but in Romanticism and Gothic novels that revere the mystical and irrational.

Barzun, Jacques / Taylor, Wendell Hertig: Introductory in A Catalogue of Crime, Harper & Row, revised and enlarge edition 1989.

In their introductory essay the authors make a knowledgeable and trenchant case for the refined literary art of detection in the tradition of the classical whodunit.

Deleuze, Gilles: “The Philosophy of Crime Novels†in Desert Islands and Other Texts 1953-1974, Semiotext(e) Foreign Agent Series 2004.

In this essay the famous French philosopher deals mainly with the difference between the traditional detective story and the crime novels of the legendary série noire, and at the same time makes interesting reading recommendations, such as James Gunn’s Deadlier Than the Male.

Eco, Umberto: “Narrative Structures in Fleming†in The Poetics of Murder, ed. by Glenn W. Most and William W. Stowe, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1983.

Eco came from scholarship to novel writing, including The Name of the Rose. Many of his essays are widely read and very well known, like this one about the James Bond stories.

Jameson, Fredric: “On Raymond Chandler†in The Poetics of Murder, ed. by Glenn W. Most and William W. Stowe, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1983.

Jameson, a literary expert above all on postmodern cultural phenomena, is also a considerable Chandler connoisseur. A more recent essay on Chandler is contained in the essay collection Shades of Noir, ed. by Joan Copjec, Verso 1993: “The Synoptic Chandler.”

Knight, Stephen: “The Golden Age†in The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction, ed. by Martin Priestman, Cambridge University Press 2003.

Knight, who is renowned for his history of Crime Fiction, 1800-2000: Detection, Death, Diversity (2003), provides a balanced and in part critical survey of the golden age of whodunit fiction.

Lacan, Jacques: Seminar on “The Purloined Letter†in The Poetics of Murder, ed. by Glenn W. Most and William W. Stowe, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1983.

The typical detective-story reader will probably be disappointed by the essay or even hate it, as he or she may get the impression that Lacan projects his concept of psychoanalysis on Poe’s story, thus monopolising it for his own purposes. Nevertheless, Lacan’s essay is one of the most frequently cited and discussed essays on Poe’s detective story; a separate volume is devoted to it: The Purloined Poe, ed. by John P. Muller and William J. Richardson, Johns Hopkins University Press 1988.

Marcus, Steven: Introduction, in Dashiell Hammett: The Continental Op, Picador 1984.

This essay is surely the most influential ever written on Hammett. The Columbia University professor shows that academic scholarship and literary form can go hand in hand.

Reddy, Mauren T.: “Women detectives†in The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction, ed. by Martin Priestman, Cambridge University Press 2003.

The essay offers a critical survey of the most important women detective writers, from Ann Radcliffe’s precursor figure Emily, to Kathy Reichs’ Dr. Tempe Brennan.

Sebeok, Thomas A. / Seboek-Umiker, Jean: “You Know My Method: A Juxtaposition of Charles S. Peirce and Sherlock Holmes†in The Sign of Three: Dupin, Holmes, Peirce, ed. by Umberto Eco / Thomas A. Sebeok, Indiana University Press 1983.

The surprising result of this comparison between the investigative methods of Peirce and Holmes is their great similarity.

Shklovsky, Viktor: “Sherlock Holmes and the Mystery Story†in Theory of Prose, Dalkey Archive Press 1991.

Shklovsky is an outstanding representative of the Russian formalist school, which had a considerable influence on modern literary studies. His collection of essays dated 1925 contains the above-mentioned essay on Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Homes stories, which can only described as “ground-breaking.â€.

Sturak, Thomas: “Horace McCoy’s Objective Lyricism†in Tough Guy Writers of the Thirties, ed. by David Madden, Southern Illinois University Press, 3rd printing 1977.

A meticulous analysis, based on Sturak’s dissertation, of the specific literary achievement of an underestimated author.

Some readers may find this list is missing academics who have rendered great service to the study of crime literature, like Francis M. Nevins, Lee Horsley, Robert Polito, Sally R. Munt, Dennis Porter, Kathleen Gregory Klein, Martin Priestman, Jochen Vogt and many more.

For anyone looking to access the wide-ranging field of the academic essay on crime literature, I would suggest the highly representative essay collection The Poetics of Murder, which is also recommended by the British Queen of Crime, P.D. James in her book on crime fiction.

— Translated by Pauline Cumbers.

Thu 31 Jan 2013

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

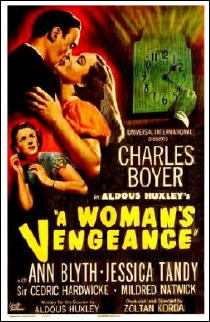

A WOMAN’S VENGEANCE. Universal, 1948. Charles Boyer, Ann Blyth, Jessica Tandy, Cedric Hardwicke, Mildred Natwick, John Williams. Director: Zoltan Korda.

A Woman’s Vengeance is undeniably a Class Act. That it also makes compelling viewing is just an added bonus. Directed by Zoltan Korda, written by Aldous Huxley (from his own story “The Giaconda Smileâ€) with a big budget and a cast that includes Charles Boyer (then past his prime as a leading man but growing in stature as an actor) Jessica Tandy and Sir Cedric Hardwicke, with support from Mildred Natwick and John Williams (the actor, not the composer; look to the right) plus a fine ingénue turn by Ann Blyth.

The story served by all this talent is one of harrowing simplicity: Boyer is an English Country Squire (by marriage) nursing a whiny invalid wife as attentively as he can while carrying on a covert affair with a younger woman (Ann Blythe, who radiates a voluptuous innocence here).

He is also being blackmailed by his worthless brother-in-law and loved from anear by neighbor Jessica Tandy, who finds daily excuses to visit the sick wife and chat with Charles.

So when the invalid wife dies suddenly, following tea in the garden with Jessica and Charles, the viewer knows almost at once what happened, whodunit and who’ll get the blame. The wonder is in seeing how skillfully director Korda and writer Huxley can play it out.

The dramatic effects sometimes seem a bit too carefully orchestrated (not unlike certain powerful scenes in the Huxley-scripted Jane Eyre of1943) such as Tandy declaring her love for Boyer in a darkened room while a violent electrical storm thunders and flashes outside; or a character gloatingly confessing guilt to another who is sitting on death row for the crime while the nearby guards studiously ignore them. But that’s just me carping; this is gripping all the way.

Jessica Tandy is brilliant here, but even better thesping comes from Sir Cedric Hardwicke, a fine actor who spent too much time in movies like Ghost of Frankenstein and The Invisible Man Returns. He plays the doctor who falls into some disrepute for mis-diagnosing the death as due to natural causes; when it’s revealed as a murder, he intuitively knows who was responsible, but he also knows that his opinion doesn’t carry much weight lately. His patient, compassionate detective work here is one of those cinematic examples of a fine actor perfectly suited to a meaty part, and much pleasure to watch.

Thu 10 Jan 2013

A TV Review by MIKE TOONEY:

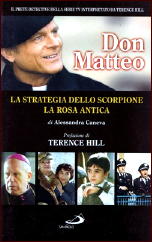

“The Strategy of the Scorpion” (“La strategia dello scorpione”). From the Don Matteo series. Season 1, Episode 5. First broadcast 21 January 2000. Regular cast: Terence Hill (Don Matteo), Nino Frassica (Marshal Cecchini), Flavio Insinna (Captain Anceschi), Claudio Ricci (Nerino), Nathalie Guetta (Natalina), Francesco Scali (Pippo), and Pietro Pulcini (Ghisoni). Writer: Carlo Mazzotta. Director: Enrico Oldoini. In Italian with English subtitles (MHz International Mysteries series).

Don Matteo is Italy’s answer to Father Brown. Terence Hill, who is most known to American audiences for his spaghetti Westerns, plays a parish priest with a knack for solving crime. Indeed, without Don Matteo many innocent people would be serving life sentences for murders they didn’t commit.

Not that the police are idiots — they’re good at their jobs but basically lack the priest’s insight into situations.

Take this episode, for instance. A prison inmate has evidently been murdered in his cell, with the valve handle from a boiler sticking out prominently from the middle of his spine. Since the dead man was known to have clashed with another prisoner (over, what else, a woman) and since this same man worked on the boiler, it looks like a simple case of murder for revenge.

But for Don Matteo, the obvious discrepancies point in a different direction: the fact that the barred window of the victim was standing wide open in freezing weather; the upside down fingerprints on the window latch; the well-kept secret that the dead man had leukemia — all of these convince Don Matteo that this crime isn’t what it appears to be.

Even after Don Matteo explains what actually happened, however, Captain Anceschi insists that without more solid evidence his solution will have to remain simply a theory.

Such solid evidence is available, though, in the form of two eyewitnesses who can give the accused man an alibi — but if they do so, it will cost them dearly.

If you know what a scorpion does when it’s in a hopeless situation (and I didn’t), you might be able to solve this one halfway through.

Don Matteo has already run in Italy for eight seasons; a ninth one is scheduled for 2013. It’s a mixed bag: usually the whodunits are easily figured out, but on occasion they’re real head-scratchers. The humor is often forced, with the best by-play between the Marshal and the Captain.

(Passing thoughts: Perhaps only in Italy could a priest enter a prison carrying a large sack of what he says are gifts and not be stopped for a search. As for the prison facilities: American criminals should have it so good.)

——————————————————————-

IMDb series listing: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0178132/

Fri 7 Dec 2012

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

While working on the last tedious chores in connection with ELLERY QUEEN: THE ART OF DETECTION, which will come out in January, I expected to devote my final column of the year to someone besides EQ. Almost anyone. But back in October Joseph Goodrich — a name you’re familiar with if you read this column regularly — emailed me a long document consisting of a large number of letters from Manny Lee to Fred Dannay that for space and other reasons he hadn’t included in BLOOD RELATIONS, his collection of the correspondence between the cousins whose byline was Ellery Queen.

Many of these letters were undated, those that had dates were often out of chronological order, typos abounded, but — Wow! For the next few weeks I alternated between slogging away at the ART OF DETECTION index and working on the Lee document: reorganizing, trying to date the letters that were dateless, adding material in brackets to explain (where I could) who or what Manny was talking about, doing pretty much the same things Joe Goodrich himself had done so well in BLOOD RELATIONS.

One item I discovered I was able to work into the text of my book at the last minute. The earliest letter in the document dates from very late 1940. Fred Dannay had recently been discharged from the hospital after suffering serious injuries in an auto accident. Manny’s letter mentions that among the people who had called asking about Fred was one Laurence Smith, whom he identifies as the ghost writer behind the then recently published novelization based on the movie ELLERY QUEEN, MASTER DETECTIVE (1940).

Laurence Dwight Smith (1895-1952) has long been forgotten but a few minutes with Google brings him back to life. Under his own name he wrote four or five whodunits, several mystery/adventure books for young adults, and a few nonfiction books like CRYPTOGRAPHY: THE SCIENCE OF SECRET WRITING (1943) and COUNTERFEITING: CRIME AGAINST THE PEOPLE (1944). His short story “Seesaw†was one of the first originals to be published in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine (July 1942). What else he may have written under other bylines, or even whether he ghosted the other EQ movie novelizations, THE PENTHOUSE MYSTERY (1941) and THE PERFECT CRIME (1942), remains unknown.

It’s long been known that Fred Dannay devised the plots for the Ellery Queen novels, stories and radio dramas and Manny Lee did the actual writing — and also that at a certain point in the nine-year life of the radio series Fred, whose wife had been diagnosed with cancer that eventually (on July 4, 1945) killed her, couldn’t perform his function any longer.

Exactly when that happened would remain unclear today except for the Lee document. In a letter written on June 30, 1948, shortly after the Queen radio program was cancelled, Manny mentions that he had taken over the series “in January of 1944, when you dropped out of active work.†For most of that year, Manny reminds Fred, he made do by recycling 30-minute scripts from earlier seasons and condensing some of the original 60-minute scripts (1939-40) to half-hour length.

Eventually, Manny says, he “began doing originals from bought material.†When? In October 1944, at the start of the program’s fifth season. Does this mean that every new weekly episode from then on was based on a plot synopsis by someone other than Fred? Not at all! Manny’s correspondence with Anthony Boucher informs us that Fred was several synopses ahead of schedule at the time he dropped out.

These Manny squirreled away and fleshed out into scripts over the next two years, the last one (“The Doomed Manâ€) being broadcast late in August 1946. But most if not all of the new scripts for the fifth season were probably based on “bought material.â€

Bought from whom? For the first several months of the new regime, the plots were devised by a long forgotten scribe named Tom Everitt. Even in the age of the Internet almost nothing is known about this man, but we know a great deal about what Manny thought of him because his letters to Boucher are full of snarky remarks about Everitt’s competence and character. On May 24, 1945, he described himself as “hating [Everitt’s] smug, treacherous guts†and Everitt’s recent plot synopses as “sloppier…even than usual….â€

His letters to Fred Dannay in the Lee document offer more of the same. On November 4, 1947, he called Everitt “a son-of-a-bitch†who at the rate of $400 per synopsis got “tremendously overpaid†even though “the bulk of the creative work was done by me, out of sheer necessity….[Y]ou don’t know the things…that bastard has been saying and is still saying in the advertising business about his ‘part’ in the Queen show. There is no protection against his kind of conscienceless and unscrupulously shrewd self-propaganda….â€

Manny would love to have worked exclusively with Boucher but Tony was unable to come up with complex Ellery Queen plots on a one-a-week basis and Manny had no choice but to continue buying from Everitt until late in the program’s radio life.

At least 33 of the Queen scripts between January 1945 and September 1947 came from Everitt raw material and are identified as such in my book THE SOUND OF DETECTION (2002). Most of the scripts between October 1944 and mid-June 1945, when the first episode based on a Boucher plot was broadcast, were probably derived from Everitt too. “Cleopatra’s Snake†(October 12 and 14, 1944) finds Ellery as backstage observer at a live production of ANTONY AND CLEOPATRA for experimental TV when the genuine poisonous snake being used in the death scene (yeah, right) bites to death the actress playing Cleopatra.

In “The Glass Sword†(November 30 and December 2, 1944) Ellery tackles the case of the circus sword swallower who died when the sword in his stomach broke while the lights were out. These concepts strike me as way too wacko to have come from the mind of Fred Dannay. Therefore they almost certainly came from Everitt.

The vast majority of Everitt-based EQ episodes have never been published as scripts and don’t survive on audio. But it now seems quite possible that one of them was mistaken for a Dannay-based episode and published a few years ago — as the title story in the collection THE ADVENTURE OF THE MURDERED MOTHS (Crippen & Landru, 2005). The episode with that title was broadcast on May 9, 1945. The plot is nowhere near as off-the-wall as those of “Cleopatra’s Snake†or “The Glass Sword†and therefore might be one of those Fred completed before he left the series. We just don’t know. Maybe we never will.

Mon 5 Nov 2012

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

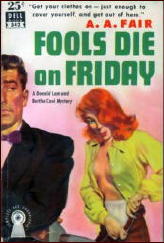

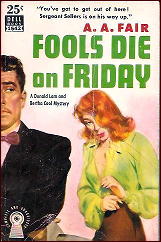

For my last column I revisited one of the Bertha Cool/Donald Lam novels written by Erle Stanley Gardner as A.A. Fair, and for this one I tackled another. Fools Die on Friday (1947) is more straightforward than Bedrooms Have Windows and the plotting more under Gardner’s control.

The firm is hired to protect a real-estate tycoon from having his food poisoned by his second wife, who married him after his first wife died of, you guessed it, food poisoning. Donald quickly catches on that his new client isn’t who she claims to be. Then he devises a scam to delay the poison plot by posing as PR man for a manufacturer of anchovy paste and offering to put Wife Two in ads for the product.

The realtor is poisoned anyway — with arsenic in the paste Donald left at his house as samples — and so is his wife. He recovers but she doesn’t. Then his secretary is strangled and Donald finds the body. Mixed into the ragout are a devious dentist, a machine that handicaps horse races, and a wandering package of arsenic.

There’s very little detection in this opus, but the pace is furious (as usual with Gardner) and the climax, with one character literally getting away with murder, would never have been allowed in a contemporaneous Perry Mason novel since the Masons were being serialized in the Saturday Evening Post and the Cool/Lam books weren’t.

Among other dividends in Fools Die we get to learn a new word. In Chapter 5 Cool tells Lam she’s trying to get the firm’s client “in a position where she has to pungle up more money.†In Chapter 15 she asks him: “You pungled up a hundred bucks in cold cash on the nose of one pony on the strength of it [i.e. the handicapping machine]?â€

I’ve never seen the word before in my life but Webster’s New International Dictionary assures me that it’s a genuine verb, meaning to pay or contribute. I wonder where Gardner came across it.

Ever hear of Walter Kaufmann? He was born in Germany of Jewish parents in 1922, left his homeland on a scholarship to an American college just before Hitler launched World War II, returned to Germany with Military Intelligence during the war, and eventually was hired by Princeton University as a professor of philosophy. I discovered him in my teens and have been reading him all my life.

Why am I recounting all this here? Because in one of his best-known books, Critique of Religion and Philosophy (1958), he tossed off a comment about our genre that is well worth preserving:

“Even as it is the fascination of a detective story that the truth is finally discovered on the basis of a great many accounts of which not one is free of grievous untruths — even as it is sometimes given to the historian to reconstruct the actual sequence of events out of a great many reports which are shot through with lies and errors…â€

The balance of this sentence is for our purposes (if I may cite a Gardnerism) incompetent, irrelevant and immaterial. I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that among Kaufmann’s favorite whodunits were those in which the detective acted as historian, for example Ellery Queen’s The Murderer Is a Fox (1945) and Josephine Tey’s The Daughter of Time (1952).

We’ll never know for sure. Kaufmann died horribly in 1980 at age 58. Anyone interested in the details can access his brother Felix Kaufmann’s account of his death by googling both men’s names.

Still bogged down as I am in the index for The Art of Detection, I’ll pad out this column to its usual length with the help of that nonpareil, that nonesuch, that Ed Word of the written wood, Michael Avallone.

Over the decades I’ve culled from his 200-odd novels well over a thousand prime specimens of the Avalloneism. Both Bill Pronzini and I as well as some others have offered samples taken from his Ed Noon PI novels, but readers of this column are less likely to have seen those he perpetrated in the dozens of paperback Gothics he wrote under female bylines back in the Sixties.

From The Second Secret, as by Edwina Noone (Belmont pb #B50-686, 1966) I’ve harvested 7½ single-spaced pages of howlers, which I hope to dole out over the next several columns. Page numbers are provided in case anyone wants to quote these in an academic journal. Hold onto your hats and here we go:

The tree had come to represent the rainbow of wishful thinking. (9)

He had been gone four long years and Cherry Williams had never stopped loving him. Like the red oak tree, she could not remember a time when she hadn’t loved dark-haired, handsome, surly Adam Freneau. (10)

The sturdy frame of his muscular young body, presaging the manhood that was to come, had engraved itself on her heart. (11)

She had only to say his name to herself or see his face in her fancies and the blood in her body would stir warmly. (13)

Cherry felt her heart stop beating, the lungs in her bosom squeeze unbearably. (14)

For a wild second, she wanted to run.

But her legs refused to heed the random irresolution of her mind. (14)

The tone of the words were worldly weary, yet unmistakably condescending. (16)

A mammoth, all-encompassing scarlet flare of color seemed to paint the world in flaming colors. (19)

(B)oth women could now hear the far off clang and trumpetry of the fire bells strategically placed all over Englishtown and vicinity. (20).

Miraculously, the stone pillars and colonnades had held off the worse that the flames could do. (20).

Of course, any number of Avallone’s Gothics are utterly devoid of such gems. When I find one of these I usually fling it across the room, snarling: “Why did I pungle up good money for this garbage? Someone edited it!†But so many of his immortal works are so lavishly studded with verbal cow pies that I could keep quoting like this till at least my 90th birthday. If there should be one.

[Editorial Comment.] 11-7-12. By the time Dell got around to reprinting their 1951 edition of Fools Die on Friday (#542), the first cover was considered risque enough that some changes had to be made. See below:

Sat 11 Aug 2012

RICHARD DEMING’s Manville Moon Series,

by Jon L. Breen

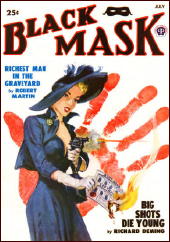

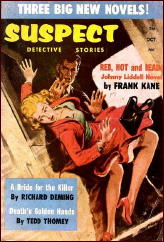

Richard Deming (1915-1983) was a solid and reliable pro whose crime-writing career extended from late 1940s pulps to early 1980s digests. He also wrote several volumes of popular non-fiction late in his life.

He is most likely to be remembered as one of the most prolific contributors to Manhunt and the early days of Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine and as a paperback original writer, sometimes of novels based on TV shows (Dragnet, The Mod Squad, and under the pseudonym Max Franklin, Starsky and Hutch). He was also a frequent ghost for the Ellery Queen team on paperback originals and for Brett Halliday on lead novelettes for Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine.

The private-eye hero of Deming’s earliest pulp stories and a number of his Manhunt stories was Manville Moon, who lost a leg in World War II, a disability that slows him down occasionally but not much.

The four full-length novels about Moon, all reissued as ebooks by Prologue Books and available at Amazon in the three-to-four dollar range, are notable for their uncharacteristic (for Deming) hard covers and (with one exception) their evocative titles. They reveal Deming to be, in common with Rex Stout, George Harmon Coxe, Erle Stanley Gardner, and quite a few others, a writer who drew on both classical and hardboiled conventions.

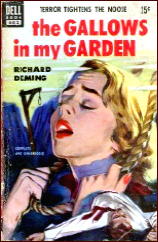

In The Gallows in My Garden (1952), Moon tells his story in smooth, relaxed, somewhat Goodwinesque first person. The terrific title comes from G.K. Chesterton’s “A Ballade of Suicide.†The setting is an unnamed Midwestern city, and the author exhibits a comfortable postwar Midwestern sensibility. The book is dedicated as follows: “To my mother, who would prefer me to write innocuous tales about members of Dover Place Church.â€

Though he will go through all the tough-guy paces, Moon is not really such a hardass and certainly a gentleman in his dealings with women. There’s some good character drawing but the secondary regulars (girlfriend Fausta Moreni, an Italian war refugee turned restaurateur; annoying comic sidekick Mouldy Green, a Moon Army buddy; and irascible friendly enemy cop Warren Day) seem made for radio.

The case is a classical whodunit setup, focused on an inheritance. Moon’s client, a 19-year-old heiress who will not collect her massive fortune until her twenty-first birthday, tells him a series of seemingly accidental close calls have convinced her someone is trying to kill her.

But it is her brother who becomes a murder victim. Many will share my immediate suspicion that Deming had lifted the plot and its ultimate solution from a very famous Golden-Age detective novel, and even those who do not know the novel in question might see that solution coming.

Does Deming have a surprise in store? Moon conducts a gathering of the suspects to reveal the generously-clued killer. The devotion to fair play puzzle spinning continues in all four novels, but this first is much the best of them.

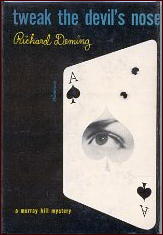

Tweak the Devil’s Nose (1953) begins with the shooting of the lieutenant governor of Illinois outside El Patio, Fausta Moreni’s nightclub and restaurant. Fausta is rich, which is a problem for Manny, a situation similar to those in many of William Campbell Gault’s novels. More of the obligatory gangsters and fight scenes are there to pay Deming’s hardboiled dues. It’s highly readable and entertaining, though not as good as its predecessor.

Give the Girl a Gun was originally published as Whistle Past the Graveyard (1954), a much better title, though the new one at least fits the story. Central to the plot is a new invention designed to prevent hunters from accidentally shooting each other. Deming inserts fisticuffs and a standard girlfriend in danger suspense sequence not vital to the main plot before another gathering of the suspects clears things up.

Juvenile Delinquent, published in Great Britain in 1958, apparently never appeared as a complete novel in the United States prior to the Prologue ebook, though it was published in Manhunt (July 1955) in a shorter version.

It lacks the light touch of earlier books in the series, offering a serious look at the J.D. problem with much preachment and speechifying included. It has a kind of procedural feel early on, reflecting a change of style and fashion in the middle fifties. The serious intent may be admirable, and I would never go so far as to miss the comic relief, but the didacticism makes this generally less successful purely as entertainment.

Fausta and the utterly unbelievable Mouldy finally appear in the second half, but the change to a lighter tone doesn’t help much. The cop contact is present but more subdued. The mystery plot is on the thin side, though the solution is typically well worked out.

In sum, Deming is a consistently reliable performer, always readable and entertaining. And admirers of the classical puzzle might see through the fisticuffs to a refreshing adeptness at misdirection.

The Manville Moon series —

The Gallows in My Garden. Rinehart & Co., hardcover, 1952. Dell #682, paperback, 1963.

Tweak the Devil’s Nose. Rinehart & Co., hardcover, 1953. Jonathan Press J-91, paperback, as Hand-Picked to Die, 1956 (abridged).

Whistle Past the Graveyard. Rinehart & Co., hardcover, 1954. Jonathan Press J-83, paperback, as Give the Girl a Gun, 1955 (abridged).

Juvenile Delinquent. Boardman, UK, hardcover, 1958. (No US print edition.)

Sat 4 Aug 2012

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

The golden oldie I picked to reread last month was The Bowstring Murders (1933), the only John Dickson Carr novel ever published under the byline Carr Dickson. I wouldn’t rank it among Carr’s top ten or even the top thirty but thought it was on the whole satisfactory, taking place almost entirely in an eerie 15th-century Suffolk castle full of the Poe-like atmosphere that the young Carr loved to generate.

Is it truly golden? According to Doug Greene’s biography The Man Who Explained Miracles (1995), Carr wrote Bowstring in New York “at white-hot speed†after his English wife Clarice discovered she was pregnant and also in order to finance a long visit to England for the family.

Greene calls the novel “badly flawed .. John Gaunt [the criminologist who solves the murders] is sharply drawn, but the plot…is unconvincing.†He correctly describes the explanation of the seemingly impossible murder of Lord Rayle as “a creative variation of the solution in [Carr’s first novel] It Walks by Night…â€

He was surprised by “how many mistakes Carr makes about England†but the ones he cites strike me as trivial: the servants “all speak a strange sort of Cockney†and after Lord Rayle’s murder the Bowstring footman fails to address the dead man’s son and successor to the title as “Your Lordship.â€

Greene also mentions “some sloppy lines†in the book but quotes only one, from Chapter 12: “With one gloved hand, he dived behind the body.†Does that sentence rise to the lofty heights of an Avalloneism? Personally, I don’t think so.

What bothered me most about the plot (am I giving away too much here?) is that, in order for the crucial gimmick to work, a cowled “white-wool monk’s robe†of the sort which the “more than half-cracked†Lord Rayle wore while wandering around Bowstring must be concealed by the murderer in an ordinary briefcase.

S. T. Joshi in John Dickson Carr: A Critical Study (1990), is no fonder of The Bowstring Murders than Doug Greene. He calls the novel a “confused and shoddily written work†and both the book and its protagonist “spectacular failures.†(Greene, as we’ve seen, disagrees with Joshi about John Gaunt.)

Joshi’s main complaint is that “the solution depends vitally upon our knowing the exact plan of the house, which is not provided.†Obviously there was no such plan in whatever edition Joshi read, and there’s none in the only edition I have (Berkley pb #G-214, 1959).

But there are several references to the local inspector making a drawing of Bowstring Castle, and I have a hunch that the sketch does appear in the original hardcover edition. If someone reading this column can tell me whether I’m right or wrong, please speak up.

If anyone decides to read the novel on the strength of this discussion, they should first go here and download the detailed diagram of the castle that Wyatt James, 1944-2006 (known to Internet mystery fandom as Grobius Shortling) kindly prepared for Carr fans who don’t have a copy of that first edition. And, if my hunch is wrong, even for those who do.

In my mailbox recently was a book that was sent from Japan but has an English as well as a Japanese title: The Misadventures of Ellery Queen. This 400-page anthology, edited by Yusan Iiki and published by Ronsosha Ltd. Of Tokyo, brings together a huge assortment of parodies and pastiches of the immortal EQ, written by such authors as Jon Breen, Ed Hoch, James Holding, Josh Pachter, Clayton Rawson and, if I may be so immodest as to say it, me. (Anyone remember “Open Letter to Survivors�)

The most recent story in the volume, and probably the finest Queen pastiche ever written, is “The Book Case†(EQMM, May 2007) by Dale Andrews and Kurt Sercu, in which Ellery at age 100 proves that his body may be feeble but his mind is sharp as ever.

Years ago Josh Pachter put together an anthology, also called The Misadventures of Ellery Queen, but could never find a publisher for it. The appearance of this new volume, coupled with the failure of Pachter’s book to find a home, provides an excellent demonstration of how tall Queen still stands in Japan and how deeply he’s sunk into oblivion almost everywhere else.

Thinking about the role of genetics in mystery fiction, we at once conjure up the DNA testing scenes in countless TV forensic series. But the subject has also figured in the Golden Age of the whodunit. In the 60-minute radio drama “The Missing Child†(The Adventures of Ellery Queen, CBS, November 26, 1939).

Ellery’s solution hinges on his assertion that it’s impossible for two blue-eyed parents to have a brown-eyed child. That was a common belief at the time, and was also crucial to the solution in an Agatha Christie story of the same decade (“The House at Shiraz,†collected in Mr. Parker Pyne, Detective, 1934).

But it’s flatly not true, as Fred Dannay and Manny Lee must have discovered sometime in the ten or eleven years following broadcast of the drama. How do I know? Because the fact of its falsity is central to one of the later EQ short stories, “The Witch of Times Square†(This Week, November 5, 1950; collected in QBI: Queen’s Bureau of Investigation, 1955).

Genetics mistake and all, the original script is included in that indispensable collection of Queen radio plays The Adventure of the Murdered Moths (Crippen & Landru, 2005).

In a column posted back in 2006 I waxed nostalgic for a paragraph or two about Boston Blackie (1951-53, 58 episodes), starring Kent Taylor in perhaps the earliest and certainly one of the finest action-detective TV series, most episodes featuring one or more elaborate chase-and-fight sequences shot on Los Angeles streets and locations.

Eighteen of the 26 segments that made up the first season were directed by Paul Landres (1912-2001), whose action scenes, brought to life by master stuntmen Troy Melton and Bill Catching, were of eye-popping visual quality, especially considering that each episode was shot in two or at most three days.

Until recently it’s been next to impossible to find decent VHS or DVD copies of Blackie segments, all of which have long been in the public domain. Which is why I was delighted to discover recently that at least twenty episodes are now accessible on YouTube — and that many of them were digitally restored last year.

I especially recommend the earliest segments like “Phone Booth Murder†(#2), “Blind Beggar Murder†(#5), “The Cop Killer†(#6), and “Scar Hand†(#11), all directed by Paul, whom I met when he was in his mid-eighties and who was the subject of a book of mine that came out about a year before he died.

Paul would have been 100 this month, and to celebrate his centenary I’ve prepared a DVD tribute that will be presented at the Mid Atlantic Nostalgia Convention in Hunt Valley, Maryland on August 11.

In one of the tapes I made with Paul he vividly described an accident that took place while he was shooting the climax of “Phone Booth Murder.†His description is now preserved on my DVD, accompanied by the climactic sequence itself.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uJ6voB6ADfE

If any readers of this column check out this episode and are interested in what went wrong and how Paul responded to the crisis, I’ll include his comments in my September column.

Sun 24 Jun 2012

A TV Review by Mike Tooney

“The Fourth Victim.” An installment of Gunsmoke: Season 20, Episode 8. First broadcast: 4 November 1974. James Arness (Matt), Ken Curtis (Festus), Milburn Stone (Doc), Buck Taylor (Newly), Leonard Stone, Ben Bates, Alex Sharp, Al Wyatt Sr., Frank Janson, Biff McGuire, Lloyd Perryman, Victor Killian, Woody Chambliss, Howard Culver, Paul Sorensen, Ted Jordan. Writer: Jim Byrnes. Director: Bernard McEveety.

Genuine whodunits set in the Old West are certainly rare, which makes this episode of Gunsmoke from its final season slightly more interesting.

A serial killer (seen only in silhouette and shadow) equipped with a .30-caliber rifle and a silencer is stalking Dodge City, murdering at will, sniper-style. Since there seems to be no obvious connection of the victims with one another, his motive is completely opaque.

Marshall Matt Dillon must turn detective to find the connection, which he does — and yet, technically speaking, he really doesn’t — halfway through the show, prompting him to think Doc Adams will be the next victim.

Using a willing Doc as bait, Dillon sets a trap, which is only partially successful, resulting in a severely damaged chair in Doc’s office and a wounded and therefore doubly dangerous sniper — who courteously sends Matt a note swearing revenge on him for interfering in his plans and calling him out for a midnight showdown — alone.

Feeling he has no better choice, Dillon appears on the deserted streets of Dodge, unaware that Doc and Festus have a surprise in store — but now fully aware of who the sniper really is ….

Since the plot centers on a woman, it’s interesting that there are no speaking parts for them in this episode. (By this time, Amanda Blake [Miss Kitty] had left the show after an argument with the producer.)

Unusually for this series, the episode takes place entirely on indoor sound stages.

Ben Bates makes an appearance in the same scene with James Arness, which is of interest since he was Arness’s stunt double throughout the run of the Gunsmoke series.

The mystery and suspense level of “The Fourth Victim” is gratifyingly high, although experienced mystery aficionados should be able to figure it out early on. If only the writer had surreptitiously introduced the final clue sooner, say in the first act, Matt’s solution near the end wouldn’t have had that rabbit-from-a-hat feel to it.

As it is, however, “The Fourth Victim” is still worth a view. It can be seen in its entirety on YouTube here.

Sun 8 Apr 2012

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

R. L. GOLDMAN – Death Plays Solitaire. Coward-McCann, hardcover, 1939. Green Dragon #10, digest-sized paperback, no date stated [1944], condensed.

While it will not endear me to the doubtless many fans of Asaph Clume and Rufus Reed, “impulsive redheaded reporter,” I must confess I am glad I read the “condensed” version of this novel since its tediousness is staggering even in the abbreviated version.

For example: “I’m supposed to be a political commentator, and I do a daily column, ‘Round-Up,’ which I sign ‘Rufus Reed’ because that’s my name.”

A former police reporter, Reed has been assigned by Clume, his boss, to cover the execution of Dan Hillyard for murder during a bank robbery from which the money has never been recovered. On his last night Hillyard gives the deck of cards with which he has been playing solitaire to his wife.

In turn, she gives the cards to Hillyard’s lawyer, who is murdered shortly afterwards. He, too, had been playing solitaire, something he had never done before, and the deck of cards has been taken by the murderer. Other deaths follow, and Reed himself faces torture and death. As Reed does the leg work, Clume does the thinking, such as it is.

Not well written even for the times, a very thin plot, an evident but clueless murderer. Still, one waits, not breathlessly, to read The Snatch, in which, according to Green Dragon, “A slipping male movie idol is the victim-and there are more than enough suspects with motives. Irrepressible Rufus Reed, red-haired reporter figures out whodunit just in time for a smashing, surprise ending that’ll leave you worrying about ethics for quite a while.”

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 11, No. 1, Winter 1989.

The Asaph Clume & Rufus Reed series —

The Murder of Harvey Blake. Skeffington, 1931.

Murder Without Motive. Coward, 1938.

Death Plays Solitaire. Coward, 1939.

The Snatch. Coward, 1940.

Murder Behind the Mike. Coward, 1942.

The Purple Shells. Ziff-Davis, 1947.

Editorial Comment: R. L. Goldman also wrote three non-series mysteries not included in the list above. Some biographical information about him can be found in the Ziff-Davis “Fingerprint Mystery” checklist compiled by Victor Berch, Bill Pronzini and myself.