Mon 7 Nov 2022

CON REPORT: Pulp AdventureCon, November 5, 2022 by Walker Martin

Posted by Steve under Collecting , Conventions , Pulp Fiction[6] Comments

Pulp AdventureCon, November 5, 2022

by Walker Martin

What a beautiful period to have a book and pulp convention! Temperature in the 70’s which is very unusual for November. Though the show is officially only one day. My friends and I celebrate the occasion from Wednesday through Saturday and some years even Sunday.

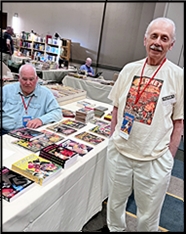

Ed Hulse.

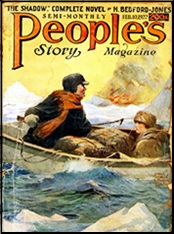

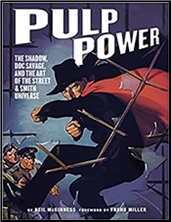

As usual Matt Moring arrives first on Wednesday and uses the extra time to research and scan pulp covers and contents. This work eventually ends up as the books published by Steeger Books (steegerbooks.com). 600 books, mostly pulp reprints and counting! An amazing achievement.

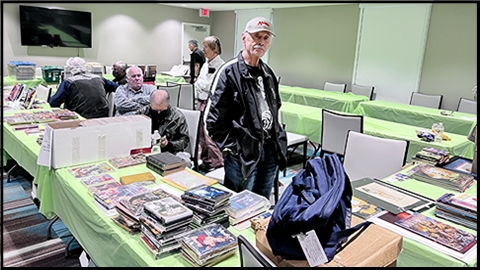

Walker Martin.

Thursday and Friday, the other pulp collectors arrive and we proceed to have several meals at such restaurants near me as Metro Grill, Bell’s Tavern, Town and Country. Sadly Mastoris Diner, after almost a hundred years, was a victim of the Covid virus restrictions but we noticed that Town and Country looked very similar as to seating and menu.

Cowboy Tony.

I try to keep the Friday brunch down to 10 collectors because that’s all I can handle and control. Yes, control, because these guys are all insane bibliomaniacs (is there such a word?) and to give you an idea here is a listing of the attendees with the years I’ve known them. They all have enormous book and pulp collections:

Digges La Touche–50 years

Scott Hartshorn–46 years

Nick Certo–46 years

Paul Herman–40 years

Andy Jaysnovich–40 years

Ed Hulse–25 years

Richard Meli–25 years

Matt Moring–10 or 12 years

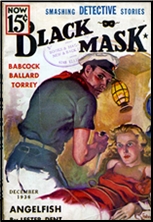

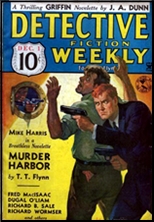

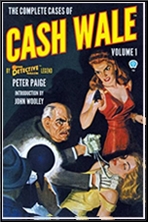

In addition we had a new guest, Peter Wolson, the son of Morton Wolson, who wrote under the name of Peter Paige for Dime Detective, Black Mask, and Detective Tales. Under his own name he also wrote for Manhunt and Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine. Peter collects only the pulps that his father appeared in so he is the only one of our group who has his collecting activities under control.

Though there were many Peter Paige stories in the pulps, he had written only one novel, so when The Complete Cases of Cash Wale appeared from Steeger Books in 2021, his son Peter was surprised and happy to see that his father was still remembered by readers and collectors.

This collection is the first volume reprinting the over 20 Cash Wale and Sailor Duffy stories. Cash was a hard boiled private eye and Sailor was his assistant and strongman. The first couple stories appeared in Detective Tales and Black Mask but the rest of them found a home in Dime Detective during the 40’s and early 50’s. The stories were long novelets and close to 20,000 words each. The author received high word rates since they were so popular. I’ve seen cancelled checks made out to Morton Wolson for $400 to $500 dollars. All the stories were hard boiled, wise cracking private eye yarns told with a sense of style and humor. I highly recommend them and they are available at steegerbooks.com or amazon.

John Gunnison.

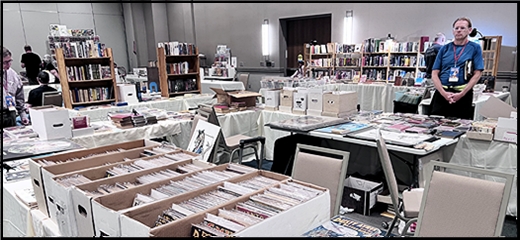

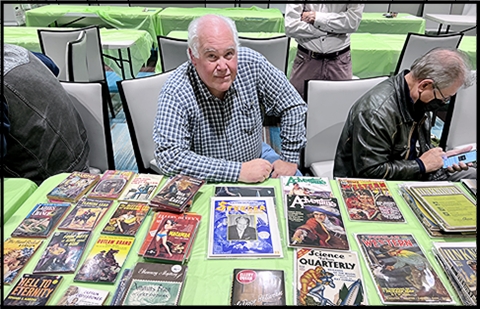

Attendance at the convention was between 80 and 100 with many dealers and 42 tables. There were two fairly large rooms and one small one. One big benefit was the free breakfast available at the hotel. I needed the egg sandwich, hash browns and coffee to get me through the day because I’m too excited to waste time taking a lunch break. Yes, “waste time,” because it’s all about the books and pulps!

Unfortunately, I’ve been at the collecting game so long that I no longer need much and I didn’t find many of my wants. But Matt Moring and I shared a table and I sold some Shadow digests, Adventure, Black Mask, and Dime Detective pulps. I saw Matt running back and forth with many pulps that he needed and it made me wish I could relive the old days when I needed a lot and had a big want list.

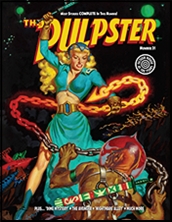

Speaking of Matt, keep an eye out for the Steeger Books Thanksgiving sale. He showed me over 20 new volumes that will be soon up for sale, including books in the Argosy and Dime Detective series.

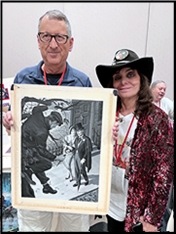

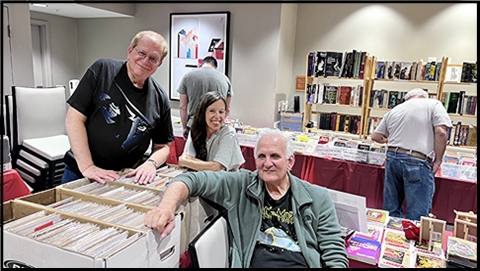

Bruce Tinkle with Lucille & Gary Lovisi.

The rooms were busy all day long, especially the tables manned by John Gunnison (five!), Cowboy Tony, Paul Herman, and Michael Brenner.

I’d like to thank the organizers of this excellent show: Rich Harvey and Audrey Parente. Also thanks to Rich’s father who has been in charge of taking attendance since the first show over 20 years ago. The photos were taken by Paul Herman. Thanks Paul! And thanks to all my collector friends for making this another memorable occasion.

Hope to see you at Windy City and Pulpfest!