TV REVIEW AND SERIES HISTORY – CHARLIE WILD, PRIVATE DETECTIVE (1950-1952)

by Michael Shonk

As a long time fan of radio’s Adventures of Sam Spade, I have wanted to sample an episode of Charlie Wild for over forty years. While there are no known surviving copies of the NBC or CBS radio show I have found an available DuMont TV episode online at tv4u.com. [Scroll down to the Charlie Wild photo and link.]

But before we get to my review let’s examine the history of Charlie Wild, Private Detective (aka Charlie Wild, Private Eye).

In radio and early television, the networks sold time slots to advertisers. Wildroot Hair Tonic paid through Batten, Barton, Durstine & Osborn ad agency to NBC for the Sunday 5:30pm half hour slot to air Adventures of Sam Spade. The series was popular with radio listeners and critics, but there were growing problems. Wildroot decided to drop the series.

Broadcasting (September 25, 1950) reported over 6,000 letters requesting Sam Spade remain on the air. Wildroot and BBD&O denied the listing of star Howard Duff in “Red Channels” as a possible communist was the cause. They claimed it was due to the need for a lower budget so Wildroot could increase its spending in television.

When Wildroot dropped Spade, it had also reduced the time slots they owned from two to one. Producer-director William Spier, who owned a piece of Sam Spade radio series, confirmed there had been an attempt to budget radio and TV versions of Sam Spade, but no agreement could be reached.

“WILDROOT DROPS ONE DICK, PICKS ANOTHER PRIVATE EYE. Wildroot, which recently dropped Sam Spade, last week bought Charlie Wild, Private Eye, for its Sunday afternoon time on NBC.” (Billboard, September 9, 1950)

NBC RADIO. September 24, 1950 through December 17, 1950. Sunday 5:30-6pm (E). 13 episodes. George Petrie as Charlie Wild. Written by Peter Barry. Directed by Carlo D’Angelo. Produced by Lawrence White.

Broadcasting (August 28, 1950): “Wildroot Co, Buffalo will sponsor agency-created program titled Charlie Wild, Private Eye…”

In Billboard (October 7, 1950), reviewing the first radio episode of Charlie Wild, Leon Morse wrote, “Cut from the Sam Spade pattern with all the familiar ingredients, this detective series should also establish itself with the aid of some sharper scripting.” Morse found “George Petrie’s acting of the private eye was slick and smooth…”

While Charlie was a rip-off of Spade, Charlie was not Sam. It was Sam Spade (Howard Duff) who introduce Charlie Wild (George Petrie) to the radio audience, according to Spade historian John Scheinfeld. Also Sam and Charlie were both on NBC radio (Spade on Friday and Wild on Sunday) November 17th through December 17th.

Wildroot wanted Charlie Wild on TV as well as radio.

December 2, 1950 Billboard reported, “NBC’s loss of the $500,000 Wildroot radio billings for Charlie Wild, and half again as much for the projected TV version, was the direct result of the web’s being in such healthy shape in TV. Because NBC-TV could not provide the sponsor with a time slot for the new video version, Wildroot approached CBS-TV. That net agreed to take the business- if the radio version switched from NBC too. Total gain for CBS – about $750,000.”

CBS RADIO. January 7, 1951 through July 1, 1951. Sunday 6-6:30pm (E). Weekly. 26 episodes.

CBS TELEVISION. December 22, 1950 through April 6 (or 13), 1951. Friday 9-9:30pm (E). Alternate weeks.

— April 18, 1951 through June 27, 1951. Wednesday 9-9:30pm (E). Weekly.

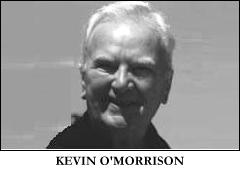

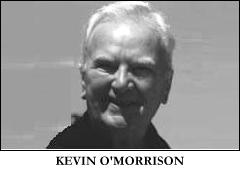

Charlie Wild played by Kevin O’Morrison (December through March), John McQuade (March 1951 through rest of series). Sponsored by Wildroot Company Inc through BBDO via CBS. Produced by Lawrence White and Walter Tibbals for Regis Radio. Written by Peter Barry. Directed by Paul Nickell.

The Billboard (January 6, 1951) review of the Charlie Wild, Private Detective TV premiere found that “O’Morrison was sufficiently engaging tele-wise as redoubtable Wild.” Reviewer Bob Francis also wrote, “What Wild needs is more original story approach and less hokum.”

Dates get confusing for the television series (perhaps some strong brave TV Guide collector could save the day). While the TV series aired on alternate Fridays, the radio series was weekly and on Sunday. It appears there were more radio episodes produced than television.

In the June 9, 1951 issue of Billboard, “…the cancellation this week of the simulcast version of Charlie Wild, Private Eye on Columbia Broadcasting System’s radio & TV networks by Wildroot… Wildroot brought Charlie Wild over from NBC, but the program failed to catch on sufficiently to make for renewal.”

That was the end of Wildroot’s involvement with Charlie, as well as the end of Charlie on radio, but it was not the end of Charlie Wild. Billboard (August 11, 1951) reported Mogen David Wine Corporation of America through agency Weiss & Geller decided to sponsor Charlie Wild and moved him to ABC-TV.

ABC TELEVISION. September 11, 1951 through March 4, 1952. Tuesday 8-8:30pm (E). Larry White Productions. Executive produced by Herbert Brodkin. Produced by Larry White. John McQuade as Charlie Wild.

In a Billboard (September 22, 1951) review of episode “The Case of the Sad Eyed Clam” written by Stanley Niss and directed by Leonard Valenta, critic Haps Kemper wrote, “Clam’s plot was routine, the script hardly scintillating, and the performances unenthusiastic…”

ABC was having major financial problems and was trying to convince the FCC to approve ABC’s desire to merge with United Paramount Theatres. (DuMont was the chief opposition. For more about that story read Billboard March 1, 1952, page 6.) Many of the advertisers panicked and removed their programs from ABC. Mogen David took Charlie Wild to DuMont.

DUMONT TELEVISION. March 13, 1952 through June 19, 1952. (*) Thursday 10-10:30pm. DuMont Presentation in association with L. White and E. Rosenberg Production. Sponsor was Mogen David Wine

(*) According to Broadcasting (July 7, 1952), Charlie was still on the DuMont schedule in July. The Los Angeles Times had Charlie airing on KTTV-TV Los Angeles at Thursday 8:30-9pm (P) as late as July 31, 1952.

“The Case of Double Trouble.” Cast: John McQuade as Charlie Wild, John Shellie as Captain O’Connell, Philip Truex as Tillinghost, Philippa Bevans as Amanda. Produced by Herbert Broadkin. Directed by Charles Adams. Written by Palmer Thompson. Television director was Barry Shear.

This was DuMont so it is no surprise the production values were cheap. Shooting live and in small sets limited the possibilities for action, forcing the story to rely too heavily on the weak dialog and disappointing cast. John McQuade performance as Charlie was lackluster.

We open as Charlie is talking into a Dictaphone to “Sweetheart.” He tells her about “The Case of Double Trouble.” It began when Charlie’s pal Police Captain O’Connell found an envelope outside Charlie’s door. The Captain and Charlie plan to have dinner together. The envelope contains half of a five hundred dollar bill and a promise for the other half when Charlie takes a unknown client’s case.

It is late Friday and despite a hungry Captain tagging along, Charlie meets the client. The client wants Charlie to protect a priceless parchment in a sealed envelope for the weekend. Charlie takes the envelope back to his office where he is knocked out by a huge ruthless woman and her pipsqueak husband.

Charlie wakes up and calls O’Connell who is still waiting for his dinner. Charlie tells his pal to go up to the client’s hotel room and keep him there until Charlie can get there.

Soon, all the characters gather in the room, there is a required fight, and all is revealed. We end back with Charlie on the Dictaphone telling “Sweetheart” there is money in the safe minus what he and the Captain spent on dinner.

“Get Wildroot Cream Oil, Charlie/It keeps your hair in trim/You see it’s non-alcoholic, Charlie/It’s made with soothing lanolin…”

One of my goals, with these research heavy reviews, is to focus on the source materials of the time the series was made in an effort to confirm or disprove the current historical views which too often is riddled with misinformation. There remains questions about Charlie Wild I was unable to confirm or disprove.

Did the series title come from the Wildroot commercial jingle that advised Charlie to get the hair product? Probably. Oddly, each of the Billboard’s reviews discussed the commercial but made no mention of any connection between the series title and the commercial jingle.

What role did Dashiell Hammett’s character, Sam Spade’s secretary Effie Perrin play in Charlie Wild? I find it hard to believe Wild’s secretary and Spade’s secretary was the same character. I found no mention of Wild’s secretary by any name, not even in the reviews. Try reviewing radio’s Sam Spade without mentioning his secretary.

Currently, it is unknown who played Charlie Wild’s secretary in the NBC radio series. It is commonly accepted today that Cloris Leachman played TV’s Charlie Wild’s secretary Effie Perrin.

Hopefully, someday a copy of the NBC radio Charlie Wild with George Petrie (who would have been a better replacement for Howard Duff as Sam Spade than Steve Dunne) will be found. I wonder what reaction the audience (to say nothing about the lawyers) had if Effie Perrin was Wild’s secretary in New York on NBC, Sunday at 5:30pm and Sam Spade’s secretary in San Francisco on NBC, Friday at 8:30pm.

There remain fifteen Charlie Wild TV episodes at the UCLA Film and Television Archive, as well as some at the Paley Center. These could hold the answer about Effie, if she did not spend all of her time off stage as she did in “The Case of Double Trouble.” Was Charlie Wild’s secretary Effie Perrin or, as I suspect, another character called Effie?

ADDITIONAL SOURCES:

On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio by John Denning.

JJ Radio logs: http://www. jjonz.us/RadioLogs

Mystery*File: https://mysteryfile.com/blog/?p=8425