COLLECTING PULPS: A MEMOIR, PART NINE —

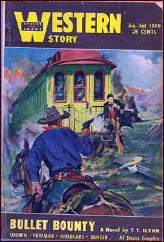

WESTERN STORY MAGAZINE

by Walker Martin

Recently, a collector of hardboiled fiction was visiting me and he noticed that my dining room was filled with stacks of WESTERN STORY MAGAZINE, hundreds of issues. In fact there were two extensive runs of the magazine, each one over a thousand issues. His first question was what on earth was I doing? A question I might add that my wife asks me each day in louder and more exasperated tones. Taking over the dining room was a major victory in the constant and bloody pulp wars between the collector and the non-collector.

I of course thought it was perfectly obvious what I was doing. I was going through the painstaking process of carefully comparing each issue in order to keep the better condition copy for my own collection. This process of having to decide which copy is the better one, has been known to drive collectors crazy.

He then wondered why I was bothering with a western magazine when he knew me as a collector of mainly SF and hardboiled fiction. After he left I started to think how did I get involved in such an enormous project as collecting western pulps. Why enormous? Because, after the love pulps, the western pulps were the most popular and best selling fiction in the 1920’s and 1930’s.

To start collecting the many titles is a major commitment in time and money. Not to mention the necessity of having the space to store them. Plus, I only collect books and magazines that I can actually read, so I have to devote some time to reading the stories. But I’ve never seen that as a big problem because I’m reading all the time: in bed, outside in the shade, while eating. The only time I’m not reading is while I’m asleep or at a book convention hunting for books. But even while sleeping I often dream about reading and what I’ve read.

When I was working and people would ask me about my job, I often responded that I was a reader and collector. Only later would I realize that they were referring to my occupation which I considered as only a means to pay the bills. We all have jobs and careers but if you are a serious collector, then your main function, your main purpose in life is often your collection. Hunting for rare items, adding to your collection, and thinking of new areas to expand your collecting interests.

And the above sentence just about explains why I expanded into the western pulp and paperback areas. I have this theory about collecting, mainly that the collector must keep expanding into other interesting areas because once you complete a collection of a certain author or magazine, then there is a danger of boredom setting in and you end up selling your collection. But if you keep collecting and getting interested in new areas, then you do not get jaded and cease collecting.

In my own case, I started out reading and collecting SF at age 13, then ten years later I started reading and collecting detective and mystery fiction, and then in a few years adventure fiction. Meanwhile I always kept an interest in mainstream and literary fiction.

I still remember the day in 1980, when I realized that I was close to realizing my pulp magazine goals. I had extensive runs of all the major SF, detective, and adventure magazines. I was mainly involved in filling in some gaps and titles. However, except for a few issues, I did not have many western pulps.

I was fortunate to be friends with a major western pulp collector, Harry Noble. Harry was quite a bit older than me and had actually bought the pulps off the newsstands. The only pulp I ever bought off a newsstand was SCIENCE FICTION QUARTERLY in 1956, just as the pulps died. So naturally Harry was the man to talk to about the western pulps.

While driving to Pulpcon in the early 1980’s, Harry regaled me with many stories of his early pulp collecting days. He started off in the early 1930’s as a boy reading WILD WEST WEEKLY. But this magazine was slanted toward the teenage boy market and he soon graduated to the more adult WESTERN STORY. This was probably his favorite magazine because of all the Max Brand stories.

By the time we returned from Pulpcon, I was desperate to collect WESTERN STORY. I asked Harry what he wanted for his set which was not complete but numbered over a thousand of the over 1250 issues. Yes, you read right, *over 1250* issues! For most of its life WESTERN STORY was a weekly, which meant 52 issues each year or 520 issues during a decade. A major title indeed.

He said $5,000 which came to around $5.00 each. Not a bad price but $5,000 was like impossible for me to pay. Like all of us, I had the usual bills to pay, car payments, mortgage, children to raise and educate, and a non-collecting spouse to care for and feed. In the early 1980’s I was earning maybe $10,000 a year which provided for a middle class lifestyle but not for a major expense like a set of WESTERN STORY.

But as some of you know, I’ve never let lack of money stand in my way when it comes to collecting my favorite addiction, my drug of choice: books and pulps. I mean this was my purpose in life, right? Since Harry and I were good friends, he trusted me to pay him $100 every pay check until the amount was paid off. So every pay check I paid Harry before any other bills. I saw the pulps as more important than such routine things as car payments, food, electric bills.

As I looked through the collection, I realized that I had made a the right decision. WESTERN STORY was one of the major pulp titles and one of the greatest success stories. In 1919, Street & Smith decided to follow up the success of DETECTIVE STORY, which had become a big seller since the first issue appeared in 1915. Just about immediately WESTERN STORY was a big success and during the 1920’s I’ve read some accounts that put sales at 400,000 and even 500,000 an issue. And this was for a weekly magazine.

The title lasted for 30 years, 1919-1949. However after the big selling 1920’s, the depression caused a decrease in the weekly circulation. The word rates were cut and Max Brand for instance, went from a nickel a word to 4 and even 3 cents. By 1934 he was no longer the main attraction and he developed other markets such as movies and other magazines.

I believe the next blow was in 1938 when Allen Grammer became president of Street & Smith. Before 1938, the firm had been mainly family run since the 1850’s, so Grammer was the first outsider to head the company. If a member of the family had been president, they probably would have had some sentimental attachment to the old dime novel and pulp days, but Grammer was strictly business. In fact, he saw the future as not the pulps but women’s slick magazines.

In 1943 came another blow when Grammer decided all the pulps would be published in digest size. All the other publishers elected to decrease pages because of the war time paper restrictions but Street & Smith started to appear in the smaller size format. It’s true that the digest size was the future but they really looked sorry compared to the larger 7 by 10 pulp size.

But he didn’t just decrease the size, he also killed several of the major Street & Smith titles such as WILD WEST WEEKLY (1927-1943, over 800 issues), SPORT STORY (1923-1943, over 400 issues), and the most missed of all, one of the greatest fiction magazines ever, UNKNOWN WORLDS (1939-1943, 39 issues).

Since Allen Grammer had no sentimental attachment to the pulps, he saw after WW II that their days were indeed numbered. He gave the order in 1949, he pulled the trigger that caused the bloodiest day in pulp publishing history, the killing of the entire Street & Smith line of pulps. The only exception was ASTOUNDING.

There have been many theories as to why this magazine survived the blood bath. I’ve heard that Grammer or one of the big shots in the organization liked SF. I’ve also heard that ASTOUNDING was on firmer financial ground and making money compared to the other pulp titles which were not that profitable.

The entire Street & Smith pulp line was dismantled and it must have been a sad and shocking day as the realization set in and the editors, staff and writers had to accept the fact that a major pulp market was indeed dead.

Daisy Bacon, one of the most senior editors with over 20 years experience editing LOVE STORY, DETECTIVE STORY and other titles was terminated. It’s reported she hated Grammer and never forgave him. In WESTERN STORY there was no advance notice, the magazine just ended with no obituary after over 1250 issues. A couple years later, Popular Publications tried to revive the title but the experiment lasted only a few issues. The pulp era was over except for a couple titles that limped on for a few years.

Now there is an amazing footnote to the above horror story (well, a horror story to a pulp collector like me!). In the mid-1990’s an elderly man moved into the house right next door to me. He was in his late 70’s and a retired music teacher. He held an open house to introduce himself to the neighbors and my wife and I attended. While walking through the house, we were stunned to see two original cover paintings from WESTERN STORY hanging on the wall of the den.

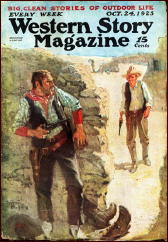

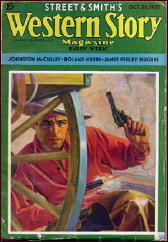

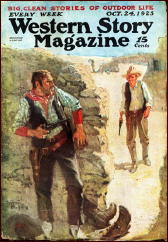

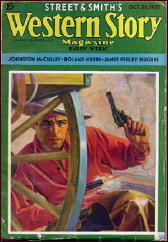

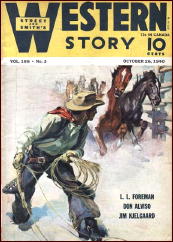

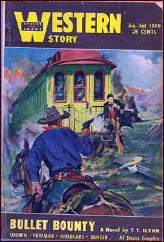

In a daze, I slowly approached the paintings and saw they were both by Walter Haskell Hinton who did several covers for WESTERN STORY in the late 1930’s (the dates of the covers are September 24, and October 29, 1938; shown to the left, and to the right below). I collect original pulp art and couldn’t believe my eyes. What are the odds of a neighbor moving next door with two pulp paintings? A billion to one?

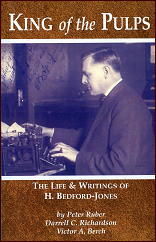

I foolishly said, like an idiot, “Hey, do you know you have two pulp paintings hanging in here, huh?” It’s a wonder he didn’t escort us out of the place. But yes, he realized it and his name was Paul Grammer and his uncle was Allen Grammer, the infamous president of Street & Smith!

He said his father also worked for the firm in some capacity and when the two brothers died, he inherited the two paintings. Paul is no longer with us but before he died he did sell me the two paintings, one of which I still have hanging in my family room as a reminder of the craziest coincidence in my life.

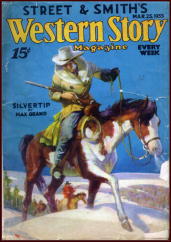

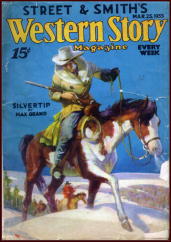

In addition to the fiction, the art of WESTERN STORY is reason enough to collect the magazine. They used several first rate artists which reminds me of another strange story. I once was in an art gallery in NYC back in the early 1980’s looking at fine art and abstract art. Then again, I was stunned to see a cover painting from WESTERN STORY. It was by Charles Lasalle and was the cover for the first Silvertip story by Max Brand.

The date is March 25, 1933 and shows a man on a horse looking at a trace of blood in the snow (shown to the left below). Again, while speaking to the gallery owner, I asked what do you want for the Charles Lasalle pulp painting. He gave me a look like I had asked him about pornography and said “We do not sell pulp art” and the way he said *pulp art* made it an obscene word.

After he quoted a high price that I couldn’t afford, I slunk out of the gallery and went home. The first thing I did was go to my WESTERN STORY collection and make sure it was a pulp cover. Then the next day I returned to the gallery with the pulp and showed the owner that the Lasalle painting was indeed pulp. He was so distressed that he sold it to me for a bargain price just to get rid of it.

Western cover art is known for the shoot ’em up images, usually a bunch of cowboys blazing away at each other. But WESTERN STORY, especially in the 1920’s, often showed scenes from a cowboy’s life. Anything from playing poker to rounding up steers at night or even chuck wagon scenes. Some favorites of mine are several covers that show cowboys reading WESTERN STORY.

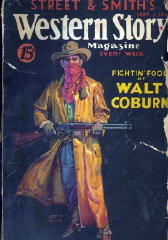

Perhaps my favorite of them all is the first cover Walter Baumhofer did for WESTERN STORY. It so impressed the editors that they hired Baumhofer to do 50 more covers including some great ones for DOC SAVAGE. It’s the cover for September 3, 1932 and simply shows a road agent with a rifle standing in the rain (shown to the right below).

Another very interesting series of covers was done by Gayle Hoskins in the early 1930’s. A couple dozen cover paintings showing scenes from “A Day in the Life of a Cowboy”. These were so popular with the readers that Street & Smith packaged them as prints and gave them away to subscribers. The vast majority of course were tacked up on walls and lost over the years. But I did manage to find a complete package with the envelope and prints that somehow survived.

I’ve saved the best artist for last. Nick Eggenhofer’s main market was WESTERN STORY for over 20 years during 1920-1943. He did many cover paintings which sell for more than I can afford but he also did thousands of interior illustrations. I have several in my collection and even these can cost a few hundred or a few thousand. There is a great book about his pulp work and working for Street & Smith. It’s called EGGENHOFER: THE PULP YEARS and copies can be found on the second hand book market.

But of course most collectors are interested in the authors. During 1920-1934 you can almost say that Frederick Faust, who wrote under the name of Max Brand and many other names, was WESTERN STORY. Some issues contain three of his stories, including the three longest such as two serial installments and the complete novel.

Though there used to be many collectors and lovers of Max Brand, we are now down to only a few. I remember in the 1960’s and 1970’s, these collectors were all over the place: binding copies of WESTERN STORY, making little homemade books out of stories excerpted from the magazine and even publishing a few fanzines.

I started reading Max Brand in 1955 but SF soon took over as my main reading addiction. I’ve always had a problem with his work and in 50 years of reading Brand I would have to say that he wrote too much and did it too fast. For many years he did over a million words a year and was one of the highest paid pulp writers. He was making over a hundred thousand a year when such money was like a million dollars. He owned a villa in Italy and wrote poetry. Unfortunately just about everybody agrees that his poetry is dated and of little interest. He was killed while serving as a correspondent in WW II.

I divide Max Brand’s work into three parts: one third is good, one third is OK but nothing special, and one third is below average or poor. I never know what I’m going to find when I read him. I might read a couple novels and think, that he is really good and that the fault has been with me for not being able to appreciate him. Then I’ll read a couple bland, sort of mediocre serials, followed by one so poor I have to give reading and I start thinking that he just wrote too fast, etc.

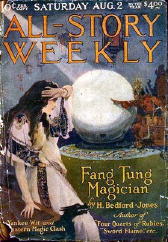

But Max Brand was not the only writer of interest in WESTERN STORY. I can recommend Luke Short who did some fine work for the magazine and went on become one of the best. Also Ernest Haycox and such excellent pulp writers like W.C. Tuttle, H. Bedford Jones, S. Omar Barker, T.T. Flynn, L.L Foreman, Robert Ormand Case, and many others.

But one of best that I’d like to specially mention was Walt Coburn. Like Max Brand, he wrote too much and too fast but he knew the west and cowboy life. In fact he was called “the cowboy author” because he actually lived the life. His western dialog and action rings true and is not false like some of Max Brand’s work. But he certainly was capable of poor work every now and then. He had a drinking problem but somehow managed to live to age 79 before hanging himself, probably due to poor health.

After buying the Harry Noble set and reading it for 20 years, I made a mistake and traded it away for some art. I figured I had read all the best fiction and could move on to something else, some other magazine that I might want to collect.

Well I figured wrong. As usual I missed the set and started to regret my decision. But fate is a funny thing and in 2006 Harry Noble told me he had a terminal illness and was expected to live only for a few months. He invited me and several other long time pulp collectors to visit him and buy magazines.

Since selling me the WESTERN STORY’s in 1980, Harry had built up his set and now in 2006, again had over a thousand issues. He agreed to sell me the set again and again for only $5,000! This time I had the money to pay him and I drove back home with a carload of WESTERN STORY. My wife was not pleased to see the magazine return home, to say the least. We all managed to say goodbye to Harry and so ended the life at age 88, of one of the greatest book and magazine collectors that I have ever known.

I could write a book about my experiences in collecting this magazine but I better bring it to an end. Wait a minute, here is another crazy collecting story. I once found out a bookstore in New Mexico had 800 issues of WESTERN STORY in nice shape from the late 1920’s to the digest years in the 1940’s. Though I had the issues already, how could I turn down their price of only 50 cents a issue if I took them all.

I frantically sent off $400 and in a couple weeks 16 large boxes of WESTERN STORY hit the Trenton post office. They evidently didn’t want to deliver them and the manager called me to come and pick them up. This actually was OK with me because then I could figure out a way to smuggle them past my wife, otherwise known as The Non-Collector.

I waited until she left for work and then I called my job and told them I’d be late due to a family emergency. I quickly picked them up from the post office, in the process almost throwing my back out due to my haste. I hid them in the basement so mission accomplished. I then went to work but I’d forgotten that I had to attend a staff meeting with some big shots. So not only was I late but my suit and tie had pulp shreds and dirt plastered all over. To make matters worse I apologized by mentioning my joy of receiving 800 WESTERN STORY pulps.

Now, one thing you cannot do as a collector and that is to try and really explain the joy you get out of collecting books or pulps. You might get away with it talking to other collectors, but not to people who collect absolutely nothing and in fact, don’t even read. For years after, my bosses would sometimes bring up the subject of my so called “western collection” in dismissive terms. It probably even cost me a promotion. The funny thing is they had no idea that the “western collection” was really just a small part of my overall collection. If they had ever known the true extent of my addiction and vice, they would have figured out some way to get rid of me.

At this point, after collecting WESTERN STORY for so many years, I’m down to needing only 11 issues but they are the hard to get 1919 and early 1920 issues, so I may never find them. But it’s been a hell of a ride and I’d do it all over again!