Sat 20 Jun 2009

THREE FOR THE SMALL SCREEN, Part 2, by David L. Vineyard: RUN A CROOKED MILE (1969).

Posted by Steve under Columns , Reviews , TV mysteries[5] Comments

Movie Reviews by David L. Vineyard

This is the second in a series of three reviews covering movies that were made for TV in the 1960s and 70s, the heyday of such film-making. Most of them were no more than ordinary, to be sure, but a few were well above average — small gems in terms of casts, plotting and production.

Previously on this blog: How I Spent My Summer Vacation (1967).

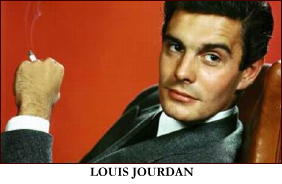

RUN A CROOKED MILE. Universal/NBC-TV, 18 November 1969. Louis Jourdan, Mary Tyler Moore, Alexander Knox, Wilfred Hyde Whyte, Stanley Holloway, Alexander Knox, Laurence Naismith, Ronald Howard. Teleplay: Trevor Wallace; director: Gene Leavett.

Richard Stuart (Jourdan) is a tutor who stumbles onto a murder in a remote English mansion. When he comes back with the law, the body is gone and he is ridiculed.

Certain he isn’t mad, he returns to London and hires a private detective, Stanley Holloway. Shortly after that he discovers a key to a room in the mansion, and is knocked unconscious.

When he wakes up, he finds he is on the Cote d’Azur, and his name is Tony Sutton, a wealthy playboy who took a blow to the head while playing polo. He’s married to the beautiful American heiress Elizabeth Sutton (Mary Tyler Moore) and he has lost five years of his life.

Who can he trust? Is his wife part of the conspiracy? Just what nest of snakes did he stumble into five years earlier?

Obsessed with finding out he returns to London to find Holloway now quite well to do and the Yard’s Inspector Huntington (Howard), not interested. Nevertheless he perseveres follows the clues back to the mansion owned by Sir Howard Nettington (Knox) and with Elizabeth’s help solves the mystery, uncovers a conspiracy, and brings down the high placed villains.

I suppose you do have to wonder why he would be so anxious to solve the murder of a stranger and risk a very good life with a rich and beautiful wife who loves him despite the fact he hasn’t been any prize as Tony Sutton, but if people behaved normally in these things, nothing would ever happen.

Run a Crooked Mile is a clever sub-Hitchcock exercise in the Buchan vein with handsome sets, and a fine cast. It moves quickly and relies on the considerable charms of Jourdan and Moore to get through whatever lags in logic that might plague you.

It’s one of those films where almost no one is quite who they seem to be, but it is done with such style and competence that it plays more like a feature than a made-for-TV film. Of the three films that will be reviewed herem it probably most deserves release on DVD.

It’s smart, funny, and suspenseful, attractive to look at, and much more literate and intelligent than it has to be. Howard, Knox, Whyte, Holloway, and Naismith all contribute nicely to the fun. In many ways it plays like a good episode of The Avengers, droll. literate, and full of twists.

Coming soon:

Probe (1969), with Hugh O’Brien and Elke Summer.