December 2010

Monthly Archive

Sat 11 Dec 2010

Posted by Steve under

PublishersNo Comments

TOP NOTCH THRILLERS

Summer & Fall 2010

This past summer’s titles from Ostara Publishing’s Top Notch Thrillers imprint which aims to revive Great British thrillers “which do not deserve to be forgotten” included a 50th anniversary reissue of a classic manhunt; the story of a World War II conspiracy from one of the biggest selling authors of the 1970s; an award-winning against-the-clock thriller; and a Gothic chiller from an author described as the literary link between Dennis Wheatley and James Herbert.

Watcher in the Shadows by Geoffrey Household is the tense, spare story of a manhunt across England’s green and pleasant countryside in 1955 which has been described by one critic “As if Gunfight at the OK Corral had been transposed to St Mary Mead.â€

Geoffrey Household, the writer widely considered to be the natural successor to John Buchan, had an unrivalled feel for the English countryside and the primitive bond between hunter and prey.

First published fifty years ago in 1960, Watcher in the Shadows is a masterly description of a deadly game of cat-and-mouse which ranks comfortably alongside Household’s legendary Rogue Male.

Black Camelot, first published in 1978, combines a superbly researched wartime conspiracy plot with blistering action and rightly led to the author, Duncan Kyle, being favourably compared to Alistair Maclean and Desmond Bagley.

Under his real name, John Broxholme was a distinguished journalist and Chairman of the Crime Writers’ Association, but it was as Duncan Kyle that he achieved international fame from the moment his first thriller, A Cage of Ice, became an instant bestseller on publication in 1970.

Francis Clifford was one of Britain’s most respected thriller writers from his first well-crafted mysteries in the late 1950s to his untimely death in 1975. His 1974 novel The Grosvenor Square Goodbye was a sensation on publication, won the Crime Writers’ Silver Dagger and was serialised in national newspapers.

The action of the book takes place in less than 24 hours and begins with a crazed lone gunman bringing the West End of London – and the American Embassy – to a violent halt. But nothing, absolutely nothing, in this ingenious ticking-clock thriller can be taken for granted.

The Young Man From Lima, first published in 1968, shows all the trademark touches which made author John Blackburn “today’s master of horror†(Times Literary Supplement).

John Blackburn held a unique place among British thriller writers of the 1960s, adding his own taste for the Gothic and the macabre to the conventions of the thriller, the spy story and the detective novel, and always at a ferocious pace. As a writer he is seen as the literary link between the work of Dennis Wheatley and James Herbert and many of his plots were based on scientific or medical phenomenon presaging the work of writers such as Michael Crichton.

7th December 2010

Top Notch Thrillers, the new imprint of print-on-demand publisher OSTARA celebrates its first year in operation with the re-issue of two classic British thrillers.

John Gardner’s debut novel The Liquidator was originally written as an affectionate spoof of the James Bond genre and featured the cowardly, accident-prone agent “Boysie” Oakes.

Originally published in 1964, shortly after the death of Ian Fleming, the Boysie Oakes books were seen as a natural successor to Bond and in the 1970s, John Gardner (by now an established thriller writer) was approached by the estate of Ian Fleming to continue the 007 franchise. In total, Gardner wrote over 50 novels, the last of which was published posthumously in 2008.

Victor Canning (1911-1986) was one of Britain’s best-loved popular novelists, whose first book was published at the age of 23 and whose writing career spanned more than 50 years. The Rainbird Pattern is probably his most famous thriller and won the Crime Writers’ Association’s Silver Dagger in 1972. It was filmed by Alfred Hitchcock (his last film) as Family Plot.

In the first year since its inception, the Top Notch Thrillers imprint has reissued 14 novels from what consulting editor Mike Ripley calls: “the heyday of British thriller writing – the 1960s and 1970s.â€

Says Ripley, himself an award-winning crime writer and a member of the International Thriller Writers organisation: “It’s a fantastic honour to be re-issuing many of the thrillers I grew up reading, but it is not just a question of nostalgia. The range and distinctiveness of British thrillers forty years ago was staggering, and the sheer quality of imaginative writing then simply does not deserve to be forgotten.â€

Full details of all Top Notch Thrillers can be found on www.ostarapublishing.co.uk. Titles are available from Amazon (£10.99 in the UK, $16.98 in the US).

Series Editor Mike Ripley can be contacted via Mike@ripley17.freeserve.co.uk

Editorial Comment: The last two are not yet available from Amazon in the US, but they can be obtained from bookdepository.com in the UK for $15.95, postpaid. (Price and availability may change quickly.)

Fri 10 Dec 2010

REVIEWED BY CURT J. EVANS:

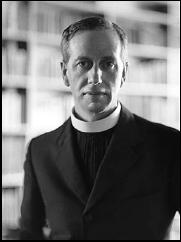

RONALD KNOX – Still Dead. Hodder & Stoughton, UK, hardcover, 1934, Pan #223, UK, paperback, 1952. US edition: E. P. Dutton, hardcover, 1934.

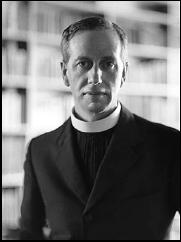

Ronald Arbuthnott Knox typifies many British writers and readers of detective fiction in that period between the World Wars we call the Golden Age of detective fiction.

Although in her recent short genre survey, Talking About Detective Fiction (2009), mystery doyenne P. D. James has written that it was Dorothy L. Sayers in the middle 1930s who made detective fiction intellectually respectable (with such “manners” crime novels as The Nine Tailors and Gaudy Night), in fact intellectuals were attracted, both as readers and writers, to detective tales at the very beginning of the Golden Age (roughly 1920), because of those tales’ ratiocinative appeal as puzzles.

For these individuals, the intellectual appeal of detective novels lay in the quality of their puzzles, not in any attempts on the part of their authors to ape the mainstream “straight” novel with compelling portrayals of social manners and/or emotional conflicts. Indeed, too much emphasis on such purely literary elements initially was often seen by common readers and more lofty genre theorists alike as detrimental in detective novels, because such an emphasis distracted readers’ minds from cold analyses of clues in their attempts to solve mystery puzzles.

One of the major literary standard-bearers for this now obsolescent view of the detective novel was an undoubtedly intellectual mystery fan and mystery writer, Ronald Knox.

Knox, a son of the Bishop of Manchester and an Eton and Oxford educated classical scholar who converted to Catholicism in 1917 (soon becoming a priest and one of England’s most prominent and articulate Anglo-Catholics), published his first detective novel, The Viaduct Murder in 1925.

Two more detective novels appeared in the 1920s (The Three Taps, 1927, and The Footsteps at the Lock, 1928), as well as Knox’s famous Detective Fiction Decalogue, wherein he laid down rules for the writing of detective fiction (all of which emphasized the puzzle aspect, or “fair play”).

On the strength of these accomplishments, Father Knox was invited in 1930 to become a founding member of the Detection Club. Three more detective novels would follow — The Body in the Silo (1933), Still Dead (1934) and Double Cross Purposes (1937) — before Knox gave himself completely over to his religious scholarship.

Less donnishly facetious than the 1920s tales, The Body in the Silo and Still Dead are commonly considered to be Father Know’s best detective novels, though oddly, they are two of the most difficult to find.

(AbeBooks lists the following number of copies for each Knox mystery title: Viaduct Murder, 27; Three Taps, 20; Footsteps, 35; Silo, 7 — all in German or French; Still Dead, 17 — though 12 of these are Pan paperback editions ranging from thirty to fifty dollars; Double Cross Purposes, 12.)

Both novels are worth reading for fans of the pure puzzle sort of detective novel, having rigorously fair play problems that even include numbered footnotes giving the pages where clues were earlier given. My preference goes to Still Dead, for its Scottish setting, over Silo, with its more hackneyed (but perennially popular) country house locale, though admittedly this is a purely literary consideration.

Still Dead concerns the death of Colin Reiver, the thoroughly undesirable heir to the Dorn estate in Scotland. Colin’s dead body was glimpsed by one of the estate’s employees, but had disappeared by the time he had left for help and returned to the spot with others.

Two days later, however, the body reappears at the same spot (still dead, hence the title). Colin is pronounced to have died from exposure, but is that really true and, either way, why were morbid shenanigans played with the corpse?

If Colin was murdered, there is no shortage of suspects. There is another employee, a gardener, whose child was run down by a drunken Colin (the latter was exonerated in court on the strength of false testimony from an Oxford friend). There are several family members, including Colin’s own father, Donald, as well as Colin’s sister, brother-in-law and cousin (truly, nobody liked Colin). There’s a family physician and also a leader of an odd religious sect to which Donald Reiver adheres.

The police write off the case (all to the good, since Father Knox evidently knew nothing about police procedure), but insurance investigator Miles Bredon (Knox’s series detective in five novels and a single, classic, short story, “Solved by Inspection”) is called in, because the question of when Colin actually died bears directly on a crucial insurance settlement (the dissolute Colin was heavily insured in his father’s favor and the Dorn estate is sadly diminished).

Still Dead starkly reveals both Father Knox’s strengths and weaknesses as a detective novelist. Positively, the fair play cluing is exemplary and reading the solution is quite enjoyable. Negatively, human interest is minimal and the plot moves very slowly.

Aside from a gentrified old lady at a hotel, Colin Reiver’s military martinet-ish cousin and a eugenics-professing doctor, none of the characters has a semblance of interest. Even these three aforementioned characters don’t come to life as they might have, given the basic material.

To be sure, Knox provides a little lightly humorous verbal byplay, courtesy of Miles Bredon’s wife, Angela (she always seems to accompany him on his investigations, despite having a child — or children, Knox is inconsistent on this point — at home). Yet Miles and Angela are no Lord Peter and Harriet, despite having preceded them into print as a mystery genre male-female duo by three years.

I found Still Dead rather more slow-moving than novels by Freeman Wills Crofts or John Rhode from this period, because Bredon’s investigation is peripatetic. Knox’s fictional works lack the relentless narrative investigative drive we see in mystery tales by those other, “humdrum”, authors, who focus so resolutely on the problem. Nor is Knox’s problem itself, though well-clued, as interesting as the alibi and murder means conundra presented by Crofts and Rhode, respectively.

In the blurb for Still Dead, Father Knox’s English publisher, Hodder and Stoughton, called Knox “a master of the English language.” Indeed, Knox is a very good writer; yet his strength as a writer is that of an essayist, not a novelist. Scattered throughout Still Dead are some fine scenic descriptions, pithy observations on religion and interesting digressions on the fate of England’s aristocracy, the nature of English gardens, chess, books, caves, hotel, etc., but, while they are interesting in themselves, by themselves they do not sustain the dramatic situation desirable in a crime novel.

Of course Knox would counter that he was merely trying to provide readers with a good puzzle, and this is a perfectly reasonable point. Admittedly, Still Dead is a good puzzle. Yet the basic material here — a dissolute gentry heir having killed a young child while driving inebriated — is interesting enough to have deserved a more serious treatment.

Knox’s handling of the material is too much on the dry side, even in the final chapter when the philosophical implications of the problem are discussed by the characters (though this is a good discussion).

Indeed, just a few years later Nicholas Blake (the pen name of poet Cecil Day-Lewis) took a rather similar plot and injected it with real human pain and suffering, in The Beast Must Die (1938), a tale much better-remembered today than Still Dead.

Even Agatha Christie, one feels, would have made a more compelling tale of Still Dead. There seems to me to have been an evident reluctance on the part of Father Knox to grapple with deeper emotions in his detective novels. (One sees this quirk as well in the half-dozen mild mystery tales by a Knox contemporary, Anglican minister Victor Whitechurch.)

Despite these reservations on my part, Still Dead is well worth reading for admirers of classical British mystery. If you can find a hardcover copy (as least this is true of the British edition by Hodder and Stoughton), you also will find a beautiful endpaper drawing of the Dorn estate and a dramatic frontispiece of stark Dorn House, both by Bip Pares, as well as that footnoted clue page guide.

The Pan paperback editions of Still Dead from 1952 that booksellers want thirty to eighty dollars for lack these graces, so charmingly redolent of the Golden Age detective novel, when many writers in their mystery tales unashamedly emphasized puzzles.

Editorial Comment: In my review of Knox’s The Three Taps earlier on this blog, I included his list of the “Ten Commandments for Detective Fiction,” also referred to by Curt.

Fri 10 Dec 2010

It’s been less than three months since Part 38 was added to the online Addenda to the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, and yesterday fifty more pages of corrections and additions were uploaded as Part 39.

Following the link will lead you to updated information on hundreds of authors and their books, and I hope you do. Much is relatively minor — birth or death dates and settings of novels — but a good deal is more substantial, consisting of biographical data, newly discovered pen names and previously unknown series characters. In a few cases, author entries have undergone a nearly complete overhaul.

And once again I’m pleased to say that some of data is generated from posts on this blog, and the followup comments. As an example, based on one that was left following Walker Martin’s memoir of Michael Avallone, it has been verified that he wrote the first Nick Carter “Killmaster” novels alone, rather than in tandem with Valerie Moolman, as was previously stated. A movie version of one his tie-in novels has also been identified.

These are but two small examples of the updating and correcting that’s still going on — Part 40 is already in progress — with input from many sources and contributors. Thanks to all!

Thu 9 Dec 2010

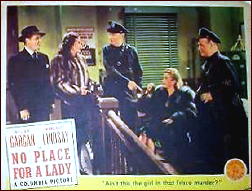

NO PLACE FOR A LADY. Columbia Pictures, 1943. William Gargan, Margaret Lindsay, Phyllis Brooks, Dick Purcell, Jerome Cowan, Edward Norris, Thomas Jackson. Screenwriter: Eric Taylor. Director: James P. Hogan.

It’s worth pointing out, I’m sure, that the two leading stars of No Place for a Lady, William Gargan and Margaret Lindsay, had just finished appearing in the last three of seven early 1940s Ellery Queen movies – playing EQ himself and Nikki Porter, respectively. (Lindsay was actually in all seven. It was Ralph Bellamy who portrayed the master detective in the first four.)

And digressing a little more before going any further, I can’t imagine either Bellamy or Gargan as the erudite Mr. Queen, but Hollywood license went a whole lot farther then than it does now.

Since Eric Taylor was involved in the writing of all seven EQ films, and director James Hogan did the last six, when it came time for them to do No Place for a Lady, it’s natural, I think, to wonder if they simply reworked a leftover Ellery Queen script, but I don’t think so. If they did, it was one heck of a rewrite.

William Gargan plays a high-powered PI named Jess Arno in this one, while Margaret Lindsay is a real estate agent June Terry, and his fiancée, She’s also the jealous type, which is important, and so is the fact that she’s a real estate agent.

Egged on by a close reporter friend named Rand Brooke (Dick Purcell), who’d like to get closer, Terry stages a fake murder in a seashore cottage she has for rent, hoping to get Arno in trouble when he leaves his latest client there, a beautiful blonde (Phyllis Brook) whom he’s just gotten off on a murder rap.

Unknown to everyone involved, a rat named Eddie Moore (Jerome Cowan) has already left his own very real murder victim there, a casualty of a scam involving a fire and hijacked tires.

Which leads to an entire movie’s worth of strange coincidences, misunderstandings, missing bodies, false leads and blaring air raid alerts, complete with the dumbest pair of shoreside cops you will ever hope to meet – or not. The fact that Eddie Moore is also a nightclub singer means that a few minutes can be taken up with a song or two.

Don’t expect any detective work to be done in this movie, and you’ll be all right. I imagine that in the movie theaters in 1943, the laughs came loud and often, but in all honesty, that wasn’t what I was watching for.

I’m always happy to have a copy of any PI movie that comes along, but while the movie isn’t actually bad, neither is it very good. In spite of its magnificent pedigree, No Place for a Lady is more disappointment than not.

Thu 9 Dec 2010

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

MARY PLUM – State Department Cat. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1945.

Touch the cat, aptly named Trouble, that wanders the State Department halls, and bad luck ensues. The last Department employee who did so was assigned to Australia and was never heard from again.

George Stair, about to take his oral exam for the Diplomatic Corps, touches the cat and fails the test. He also has secret papers stolen from him, is hit with the ever popular blunt instrument, and suffers various other unpleasantnesses while dealing with a would-be Latin-American dictator and a Nazi spy.

An occasionally amusing thriller that will probably appeal only to those interested in the Washington, D.C., area, and maybe not to them. Still, it’s far better than Plum’s mysteries featuring John Smith.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 11, No. 4, Fall 1989.

MARY PLUM. 1904?-1991? Series character: John Smith [JS].

The Killing of Judge McFarlane (n.) Harper 1930 [JS]

Dead Man’s Secret (n.) Harper 1931 [JS]

Murder at the Hunting Club (n.) Harper 1932 [JS]

Murder at the World’s Fair (n.) Harper 1933 [JS]

State Department Cat (n.) Doubleday 1945

Susanna, Don’t You Cry! (n.) Doubleday 1946

Murder of a Redhaired Man (n.) Arcadia 1952

— The information above was adapted from the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin.

Note: The first four books are all also Harper Sealed Mysteries. Of Dead Man’s Secret, an online list of novels taking place in Illinois says: “Most of the people at Gray Manner’s house party are glad to see Rook Chilvers get what’s coming to him, but no one is willing to admit the murder. As the case develops and evidence implicates first one guest then another, even the cool, logical John Smith, a professional Chicago detective, seems puzzled.”

Wed 8 Dec 2010

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

SHOOTING STARS. British Instructional, UK, 1927. Brian Aherne, Annette Benson, Chili Bouchier, David Brookes, Donald Calthrop. Director: A. V. Bramble, assisted by Anthony Asquith. Shown at Cinefest 28, Syracuse NY, March 2008.

A stylish silent film, with Annette Benson as the wife of actor Brian Aherne and his co-star, who has a fling with film baggy-pants comedian Donald Calthrop.

She wants to leave Aherne for her lover, but fears it will destroy her career. She substitutes real bullets for blanks in the gun that will be fired at Aherne in their thriller, but even though she decides not to go through with it, a series of misadventures results in the shooting of Calthrop and Benson’s withdrawal from films and her marriage.

There’s a final sequence in which, several years later, she has a walk-on in a film directed by Aherne, unrecognized by him or anyone else in the crew, with a poignant fade-out as she appears to walk away walks away forever from her former husband and the movies.

The behind-the-scenes look at the filming of silents, made this absorbing, ironic drama of unusual interest.

Wed 8 Dec 2010

THE PLOT THICKENS. 1936. James Gleason, ZaSu Pitts, Louise Latimer, Owen Davis Jr., Richard Tucker. Based on a story and characters created by Stuart Palmer. Director: Ben Holmes.

The role of Hildegarde Withers in this next-to-the-last movie based on her adventures with Inspector Piper was taken over from Edna May Oliver then Helen Broderick by ZaSu Pitts, whose fluttery hands and ways are best taken in small doses. She seems to fit the part, however, given Hollywood’s perspective on the stories.

This has come up before, and in the meantime I’ve given this some small amount of thought to it — the business of detective stories being made into comedies when converted to the silver screen, especially during the 30s and 40s.

Maybe it’s because the idea behind the traditional, cozy detective murder mystery is inherently ridiculous to begin with — the established routine of a victim, suspects, clues, questioning, locked rooms, alibis and so on.

Could it be, when transferred into cinematic terms, the whole entire unlikelihood of the proceedings is amplified into the utterly absurd?

That’s the question as I’ve reformulated it so far, and I haven’t answered it yet, but why else did so many favorite mystery characters turn into bumbling idiots when portrayed on the screen?

Or why did their adventures need to “enlivened” by the presence of goofy chauffeurs, clown-like cops or (simply) funny friends? Hard-boiled operatives fared much better. I don’t think Hollywood had a very great opinion of the Ellery Queen’s or Hildegarde Withers(es) of the literary world.

Which is not to say that I’m bitter — but wouldn’t it have been better to have had Jean Arthur play Pam North than Gracie Allen? Wouldn’t Sara Haden (Andy Hardy’s Aunt Millie) have made a better Hildegarde Withers? (It could have been worse — they might have used Marjorie Main.)

This not being an ideal world, however, simply the best of all possible ones, we accept what we’re given. As the title indicates, there’s a lot of plot in this one: first of all a murder, with lots of suspects, including a butler and a jealous boy friend. There also turns out to be a stolen emerald in the dead man’s possession, and the whole affair ends up in a museum where the famous Cellini cup is the target of a gigantic gang of thieves.

Simply terrific stuff!

James Gleason, as Inspector Oscar Piper, is a pint-sized bantam with an irascible temper and even fouler-smelling cigars. As a detective, well, it’s no wonder he had Miss Withers along to do his thinking for him.

— Reprinted from Mystery*File #35, November 1993, slightly revised.

[UPDATE] 12-08-10. When I wrote this review, I was unaware of a made-for-TV movie in which Miss Withers (Eve Arden) and Inspector Piper (James Gregory) were also the leading characters. It was A Very Missing Person, based on the novel Hildegarde Withers Makes the Scene by Stuart Palmer and Fletcher Flora. Shown on ABC, 4 March 1972, rumor has it that it was not as good as it might have been.

And a fact that was totally unknown to me until just now, according to Wikipedia, there was a 1950s TV sitcom pilot entitled “Amazing Miss Withers” that starred Agnes Moorehead and Paul Kelly. It is apparently considered lost, probably forever.

Tue 7 Dec 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

IT IS PURELY MY OPINION

Reviews by L. J. Roberts

DICK FRANCIS and FELIX FRANCIS – Crossfire. Putnam, hardcover, August 2010. Paperback reprint: August 2011.

Genre: Amateur sleuth. Leading character: Tom Forsythe; Dick Francis’s 45th book. Setting: England.

First Sentence: Medic! Medic!

Captain Thomas Forsythe has returned from fighting and being injured in Afghanistan, to a place called home in name only. He and his mother have never been close. She is a well-known, well-respected, successful trainer of racehorses and at risk of losing everything to a blackmailer and/or the Inland Revenue. For the first time ever, Tom can help his mother; if she would only let him.

One thing on which you can always count with a Francis novel is a captivating opening and this book does not disappoint. It begins with a bang, literally, and is both current to our time and effective.

After that, I must admit, the old charm wasn’t quite there. Tom is an effective character and classically Francis; he’s independent, a loner, self-reliant and determined. He was certainly the best of the characters in the story, and the most well developed.

It may sound silly, but I enjoy that the author’s voice, particularly with both the author and the characters being British, sounds British without an attempt to Americanize it. There was a strong sense of place, I feel I’m coming to know the Lambourn region.

Details make a difference. The inclusion of information on Tom’s life in the military, including what the infantry wears and carries with them, but also information on the tax system; these things add dimension to the story.

Taking into account that I was reading an uncorrected proof, there was a good deal of redundancy. I hope that won’t be true with the finished edition. The plot was good, but lacked the suspense to which I’m accustomed and a number of the situations were strikingly, and rather uncomfortably, familiar from previous books.

Remembering specifically which books definitely took me out of being involved in reading this one. One of the classic Francis elements was missing; the protagonist was never involved in a fight. Considering the occupation of the protagonist, this was one book in which he could really have held his own. Maybe that’s why it wasn’t included, but I certainly noticed the lack of it being there.

What did work, however, was the climax. It was unexpected, somewhat shocking and one of the best from Francis in awhile. The epilogue was well done and it is always important to me to know justice is served.

For all its faults, I don’t regret having read Crossfire. It will be interesting to see how the Francis name and style progresses from here.

Rating: Good.

Tue 7 Dec 2010

REVIEWED BY J. F. NORRIS:

MAX LONG – The Lava Flow Murders. Series detective: Komako Koa #2. J. B. Lippincott, hardcover, 1940.

After an expository overload in which the characters are introduced in quick succession, the first third of the book is spent on detailed descriptions of a volcanic eruption and the attempts of plantation policeman, Komako Koa, and the plantation owner, Tucker, in evacuating the visitors who have recently arrived from a yacht in the harbor.

They are also told to avoid a heiau (sacred Hawaiian shrine) to Pele. But two members of the party mock nearly everything to do with traditional Hawaiian beliefs and culture. One of those mockers, a brash woman, enters the heiau and is seen arguing with someone who the visitors believe is the embodiment of Hawaiian goddess Pele.

The woman is almost immediately discovered dead — her head crushed by a coconut. For some reason the mainlanders actually believe that Pele is responsible and there is a lot of silly melodrama with people running around crying out to beware of Pele.

None of this makes any sense. Koa takes advantage of this and rather than telling everyone that he knows the woman was murdered he lets them indulge themselves in superstitious gullibility. Irresponsible of a policeman and a bit contrived on the part of the author. But without that the rest of the story would not follow.

Meanwhile, the volcano continues to erupt and encroaching lava flows continue to threaten the characters as well as the ranch house where they are staying. Then another person is hit on the head with a coconut and yet another person disappears.

Soon it appears that a homicidal maniac is at work and the book takes on the atmosphere of And Then There Were None set in Hawaii with an active volcano as an added menace.

Koa’s friend and the series narrator, Hastings Hardy, believes that a local Hawaiian has gone mad and is acting as a murderous nemesis for the offended Pele. There is a character called “the firewalker” who fits this bill. But Koa says no Hawaiian would enter a heiau and commit murder let alone do any of the other horrid things that the killer does (for example, a woman is thrown into the steaming, fomenting ocean where the lava flow ends and is basically boiled to death!).

The book is not very well constructed and — believe it or not — is often dull. It’s a hodgepodge of a disaster adventure comprised of lots of scientific detail about volcanoes, lava flow, the different types of lava and how they behave, the types of rock and ash that accompany violent eruptions, etc. etc.

The murder mystery is thrown in almost as an afterthought. The book could easily have been much shorter and the narrative handled less clumsily had the author focused on the story rather than focusing on the volcano and the lava.

The only thing that holds one’s interest is the interspersing of Hawaiian lore and legends. The culprit, once one accepts Koa’s dismissal of anyone Hawaiian, is a bit obvious. The killer’s motive, set up also rather obviously way back in the first chapter when land rights and inheritances are discussed, and the denouement overall are less than satisfying.

LONG, MAX (Freedom). 1890-1971. SC: Komako Koa, in all.

Murder Between Dark and Dark. Lippincott, 1939.

The Lava Flow Murders. Lippincott, 1940.

Death Goes Native. Lippincott, 1941.

— Taken from the

Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin. A short biographical article about the author may be found

here on Wikipedia.

Tue 7 Dec 2010

J. B. O’SULLIVAN – Someone Walked Over My Grave. T. Werner Laurie Ltd., UK, hardcover, 1954. No US edition.

As I often do, I’ll append a list of all of J. B. O’Sullivan’s Steve Silk mysteries at the end of these comments. There are a few of them, as you’ll see, but only two have even been published in the US.

Silk himself is described on the Thrilling Detective website as “a former boxer turned un-licensed PI. Quick with a wisecrack and quicker with his fists, he dresses well and chases women with vigor,” but there are no signs of fisticuffs in the book at hand, and no woman chasing either.

Silk is usually based in New York, so maybe the difference is that when he visits Ireland, as he does in Someone Walked Over My Grave, he’s on his best behavior. In fact the murder that’s solved in this book is a country manor affair, one much more suited for the likes of Supt. George Tubridy than a smooth as silk operator like Steve.

There is a point in time, however, at which the reader (this one, anyway) will suddenly realize that what is going on is a competition between the two. Who (and which approach) will solve the case first? Amusingly, though, the two end up asking the same questions of the same people and each in their own fashion, coming up with very much the same answers.

Dead is the father of a would-be bridegroom, and the number one suspect is the wayward brother (on the other side of the Irish political divide) of the would-be bride when it appears the wedding is off (therefore all of the would-be’s). Telling the story is Jimmy (no last name noted), a local reporter who spent some time in the US chronicling some of Silk’s earlier adventures.

In the grand Golden Age of Detection fashion, there are lots of suspects, some with alibis, some not, and some of the alibis are suspicious if not outright flimsy. There are several decent twists before a suspect admits to having done the crime, then an even better one before (PLOT ALERT, and maybe I shouldn’t even be telling you this) the last three paragraphs turn everything around again.

An amazing feat. I was on cruise control at the time, and it made me stop on a dime, sit up and take notice, I’ll tell you that.

The Steve Silk novels — [Adapted from the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin]

Casket of Death (n.) Grafton 1945

Death Came Late (n.) Pillar 1945

The Death Card (n.) Pillar 1945

Death on Ice (n.) Pillar 1946

Death Stalks the Stadium (n.) Pillar 1946

I Die Possessed (n.) Laurie 1953. US: Mill, 1953

Nerve Beat (n.) Laurie 1953

Don’t Hang Me Too High (n.) Laurie 1954. US: Mill, 1954

Someone Walked Over My Grave (n.) Laurie 1954

The Stuffed Man (n.) Laurie 1955

The Long Spoon (n.) Ward 1956

Choke Chain (n.) Ward 1958

Raid (n.) Ward 1958

Gate Fever (n.) Ward 1959

Backlash (n.) Ward 1960

Make My Coffin Big (n.) Ward 1964

Murder Proof (n.) Ward 1968

The Supt. George Tubridy novels —

Someone Walked Over My Grave (n.) Laurie 1954

Pick Up (n.) Ward 1964

Lunge Wire (n.) Ward 1965

« Previous Page — Next Page »