October 2011

Monthly Archive

Sat 22 Oct 2011

Posted by Steve under

ReviewsNo Comments

A REVIEW BY MARYELL CLEARY:

CHARITY BLACKSTOCK – Dewey Death. London House, US, hardcover, 1958. Ballantine U2125, paperback, 1964 (shown); several later printings, including one in 1985 referred to here. Originally published in the UK: William Heinemann, hardcover, 1956.

When a book originally published more than twenty years ago is reprinted, I’m always curious about how well it has withstood the passage of time. In the case of Dewey Death, the answer is “Fine!”

The Dewey Decimal System no longer has the widespread use that it once had, and Mr. Dewey’s idiosyncratic way of spelling never did. Since these figure only in chapter headings, that doesn’t matter much, and indeed give the book a certain out-of-the-way charm.

In Dewey Death Blackstock shows us a young woman progressively fascinated and ensnared by a fellow whom we’re not sure about. Perhaps he’ll turn out to be the hero, perhaps the villain. Both work in the Inter-Libraries Dispatch Association; both — and their co-workers as well — have good reason to dislike Mrs. Warren.

If anyone has a secret, Mrs. Warren can’t rest until she finds it out, and some secrets are dangerous to know. Mrs. Warren is killed. Barbara Smith, librarian and writer of novels; Mark Allan, who is enmeshed in a romance with the elusive Mrs. Bridgewater; the young Mr. Wilson; the “girls,” Greta and Maureen, and all the other employees, move in an atmosphere of suspicion, doubt and, finally, terror.

This book moves from a quiet beginning through mounting suspense to a crashing conclusion that left this reader breathless. Its reprinting was well deserved.

— Reprinted from The Poisoned Pen, Vol. 7, No. 1, Fall-Winter 1987 (slightly revised).

Sat 22 Oct 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[8] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

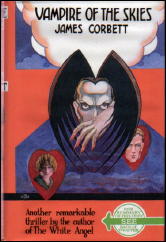

JAMES CORBETT – Vampire of the Skies. Herbert Jenkins, UK, hardcover, 1932. No US edition.

Reviewing a James Corbett novel is a challenging task, the reviewer says modestly. The temptation is to quote the entire novel, getting the ordeal over with by causing no pain at least to the reviewer, since no one is likely to believe what is to be said about the novel.

As Corbett himself put it in another and even worse — or better, depending on your point of view — novel: “The whole thing is so fantastic as to appear incredulous.” But in recognition of our esteemed editor’s sensibilities, the temptation to reprint the book will be resisted.

This is the fourth James Corbett novel that this reviewer has read. The first, The Merrivale Mystery, was recommended to Bill Pronzini as an “alternative classic,” and Mr. Pronzini agreed that it fit that category.

The second was The Monster of Dagenham Hall, which is essentially The Merrivale Mystery revisited, and thus a howler in its own right, although it would be bad enough standing on its own.

(Corbett, at least in the books mentioned, will be appreciated by those who enjoy the egregious mystery. His Red Dagger, on the other hand, does not deserve to be described as awful; it is merely poor. But not to read the novel, and no one but a masochist should, would mean missing a gem from the literature, so it is provided herewith:

(“Have you a cigarette?” she asked.

(“Cavanagh threw his case on the desk.

(“You seem upset?” he suggested, lighting a match and holding it to her lips.”)

There are certain types of readers to whom Corbett will not appeal. He should be avoided by those who like fine writing; by those who appreciate good description; by those who enjoy characterization and who think it helpful to be able to tell the characters apart; by those who do not appreciate non sequiturs or the almost-right word; by those who think real clues are essential in a mystery; by those who want detection and fair play; and by those who expect a writer to remember what he has written just a page before.

Finally, Corbett should be shunned by those who do not care for low, albeit unintentional, humor and who therefore do not find the following quotations risible:

First it made him furiously angry, then apoplectic, then diabolically insane with rage, and for the last quarter of an hour it affected his stomach.

* * *

Then he thought of England and Horatio Nelson, of Drake, Cabot, and Mussolini, of the multifarious regulations of the British Police Force, of the Westminster Confession of Faith, and sundry little oddments, then perspired up the ladder.

“Corbett for thrills” is what his publishers say about him. “Corbett for laughs” is my description, unless the preposterous happens to thrill you.

If anyone is still reading at this point, except for the long-suffering editor who must read this review before he rejects it, a doomed effort to describe what the book is more or less about:

A police constable observes an airplane flying at an estimated 2,000 feet in a “circumlocutory motion,” whatever that might be. The plane circles him seventeen times, and then a body is hurled from the plane onto a hayrick. On investigation, the constable discovers the corpse of “a remarkably young woman,” who later we are told looks 25 and is actually 23. This isn’t important, as much as Corbett tells us isn’t important, or interesting, or even correct, when it’s not downright contradictory.

The body has a gaping knife wound somewhere, though it’s a little unclear where, and around the wound are the “marks of animal-like teeth. The murderer has actually drank his victim’s blood.” The latter is a conclusion that is never substantiated, but the vampire of the title has to be justified.

The corpse at one time is wearing a brown mackintosh and at other times is not and has “disordered hair,” as if that’s a surprise after a free fall of 2,000 feet followed by a rather abrupt halt.

Well, the Yard sent down Malcolm Dacre. That act, in itself, showed intelligence. Manifestly Scotland Yard proved itself a going concern. But it has been going a long time….

This gives you some idea of Corbett’s prose and exposition style. It doesn’t get much better than this worse. How could it?

It was the Birmingham case that made him [Dacre] famous, where Reuben Morrison, a well-known jeweller, was found with his throat cut. Dacre disposed of the suicide theory….

There are no flies on Dacre, you’ll note.

Malcolm Dacre was what he looked. He never tried to look otherwise. He was an intellectual, and, with it all, he was genuinely modest. There was real discernment in his dark, glowing eyes, and the trick he had of bringing his lips together boded ill for any chance suspect….

He had seventeen crime solutions to his credit — “scalps,” he called them – -and, in every instance, they were murder cases where no clue presented itself.

Since there is one clue in this case, Dacre is obviously ahead of the game. He finds the clue — “the complete half of a gold bangle,” leaving us to wonder what an incomplete half might be — in the hayrick and conceals that fact from everyone, including his chief.

Perhaps, in some mysterious way, that other half would come into his possession. If it did, he would recognise it. How? That was his secret.

And he keeps his secret, for the bangle is never mentioned again.

Among other problems that Corbett has is a strange time sense, or Dacre is very fast with foot and mouth. At 10 p.m. Dacre decides to dine at a hotel. He orders and eats his meal, smokes a cigarette, is called to the local police station that is three minutes away, interviews the man who might be the father of the victim, discusses the case with the Chief Constable, and walks back to the hotel, arriving there “about ten-thirty.”

Later on, Dacre himself observes a plane circling seemingly the mandatory seventeen times — we are never vouchsafed an explanation for this behavior by the plane’s pilot or even told why anyone was counting — and another body is thrown out, from about 4,000 feet on this occasion.

This time the body hits the ground. As might be imagined, “the body was crushed beyond all recognition.” Well, except for the face and the area of the knife wound with the teeth marks around it. Corbett isn’t going to let small things like physics and blatant contradictions spoil a good story.

As an example of the author’s very short memory — indeed, from one page to the next — the suspect, whose own plane, an Avro, is not available, escapes our less-than-keen detective: “When our backs were turned, he darted like a shot across the lawn, climbed into that Bristol Fighter, and, with the aid of the efficient self-starting apparatus, got away like a flash of lightning.”

Captain Trevor Holmes, who is working with Dacre, takes off in that same Bristol Fighter to pursue the villain. “He has gone after your suspect, Dacre, and I believe he will catch him. Remember, he has got a Bristol bus, with one of the new model Jupiter engines, and at the rate he is going, no Avro could possibly keep ahead of him.”

Some other items are the detective’s searching “furtively” while being watched by three people, the odd impression that a red herring is a lure, the wonderful notion that “Oh yeh!” and “Sure thing!” can be said with an “American twang,” the puzzling simile, “It was like looking for an ostrich in a forest of monkeys!” to describe something difficult to locate, the detective’s superlative deduction of “Your daughter was a straight, God-fearing girl. That is the impression she has given me — even in death!”

Finally, this description of Mountdale, the villain’s residence, which frankly baffles this reviewer: “It somewhat resembled the French villas found at Paris Plage, except that the design was entirely English, while in that respect it was unique.” (Explanations on a postcard, please.)

There is only one suspect in the novel, so spotting the bad guy is not exceptionally difficult despite the lack of clues. Corbett’s general rule is to make the most likely person guilty; when he doesn’t make the guilty person someone who has not appeared in the case until the end of the book.

Still, there is a kicker of the most improbable sort at the end based on something the detective had noticed seven years before but hadn’t shared with anyone. As Dacre himself puts it: “This case is approaching an anticlimax.”

Yes, indeed. And it also reaches an anticlimax.

— From The Poisoned Pen, Vol. 7, No. 1

(Whole #33), Fall-Winter 1987.

Editorial Comments: James Corbett was the author of approximately 40 detective novels published between 1929 and 1951, all from the same publisher. (After reading this review, blackmail is suspected, by me, at least.) Of these, only two have US editions.

In spite of Malcolm Dacre’s reputation as a detective, this is the only case of his to have been reported upon by James Corbett. Of the various detectives in his list of fiction, none of them ever made a return appearance.

The author’s books are quite scarce. At the present time, there appears to be only one copy of Vampire offered for sale by anyone on the Internet, this one in Good condition with no jacket. The asking price, in case you’re interested, is $88 and change, including postage.

Fri 21 Oct 2011

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

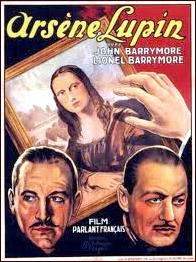

ARSÈNE LUPIN. MGM, 1932. John Barrymore, Lionel Barrymore, Karen Morley, John Miljan, Tully Marshall. Adapted from the stage play by Maurice Leblanc and Francis de Croisset. Director: Jack Conway.

John Barrymore plays Lupin and Lionel Barrymore is Inspector Guerchard, with Karen Morley playing a criminal who agrees to help Guerchard trap Lupin in exchange for her freedom.

There is some disagreement among, the various characters on the proper pronunciation of “Arsène,” with Lionel the must skillful at mispronouncing it, but this is a charming film climaxed by a spectacular theft of the Mona Lisa from the Louvre.

Morley, predictably, falls in love with Lupin; the Lupin character is laundered in the final scene to provide a conventional ending, and the transition from play to movie is not always successful. But John Barrymore plays the gentleman master criminal with an ease and casualness that give the film an illusion of freshness and spontaneity, while Morley is a beautiful and elegant foil to the two brothers.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 8, No. 4, July-August 1986.

Thu 20 Oct 2011

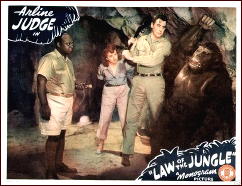

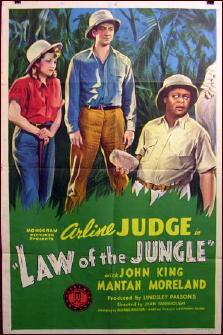

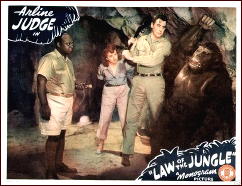

LAW OF THE JUNGLE. Monogram Pictures, 1942. Arline Judge, John King, Mantan Moreland, Arthur O’Connell, C. Montague Shaw, Guy Kingsford, Laurence Criner, Victor Kendall. Director: Jean Yarbrough.

I didn’t begin watching this movie with high expectations, and after five minutes, I was ready to turn it off. I’d seen it all before, I thought, and far better done, and this assuming I wanted to see another girl-singer-stranded-in-the-African-outback movie again in the first place.

But something caught my attention – maybe it was Arline Judge, a good-looking brunette with beautifully expressive eyes – or maybe it was Mantan Moreland, playing another comedy role in a low budget picture as “Jeff,†in this case the fellow heading up John King’s safari into the jungle looking for bones.

Or maybe it was the only player in this movie who later on received two Oscar nominations, Arthur O’Connell, the grizzled, dissipated and thoroughly crooked owner of the traders’ bar where Arline Judge has been stranded without a passport, which O’Connell, unknowing to her, has in his possession.

Palaeontologist John King, whom Arlene calls “Professor,†is her only lifeline out of Africa, as well as her means of escape from some Nazi-like fellows that O’Connell is in cahoots with.

Which just about explains everything, including perhaps why I kept watching. And enjoying myself, especially the scene in the moonlight in the jungle with Arlene Judge’s head on John King’s shoulder, and he totally oblivious to her charms.

In movies made by Monogram in their heyday, scientists were either mad, you see, or hopelessly naive. (John King’s acting is also as stiff as they come, but among other highlights of his career, he was one of the Range Busters in a series of early 40s B-westerns for Monogram after having the title role in the Ace Drummond serial in 1936.)

There is also later on a guy dressed up in a gorilla suit, and Mantan Moreland learns not to say “Scrambola†to the head chief’s hefty-sized daughter when trying to persuade her to release him and the other two stars of this motion picture. Whenever Mr. Moreland is on the screen, this movie is a comedy. When he’s not, it’s a below average jungle adventure, but believe it or not, none the worse for it.

Wed 19 Oct 2011

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

RIDE THE PINK HORSE. Universal, 1947. Robert Montgomery, Thomas Gomez, Rita Conde, Iris Flores, Wanda Hendrix, Fred Clark, Andrea King, Art Smith. Screenplay: Ben Hecht & Charles Lederer, based on the novel by Dorothy B. Hughes. Director: Robert Montgomery.

Starring and directed by Robert Montgomery, Ride the Pink Horse is not a great film by any means, but interesting throughout. Montgomery had, by all accounts, an unusually high IQ, and it has always seemed to me that his films are all marked by an almost intangible quality of Intelligence.

The failures as well as the successes seem to presuppose a certain degree of Smarts on the part of the movie-going audience (a classically underestimated group) and work from there.

The well-known extended subjective camerawork in Lady in the Lake, for example, is hardly an unqualified triumph, but it’s the sort of thing somebody had to try sooner or later; all it took was a director who had some confidence in his audience.

Likewise the sly references in Montgomery’s autobiographical daydream-movie Once More, My Darling, where Ann Blyth conveys a hitherto-unsuspected and startling sensuality while we wait for things to get funny, which they never really do.

Montgomery’s intelligence often showed itself even in films he didn’t direct but merely acted in. There’s his effete quisling in The Big House; the blandly ingenuous psycho in Night Must Fall; the Detective/Prince in Trouble for Two; and the memorable Here Comes Mr. Jordan and They Were Expendable, all films marked by much more thoughtfulness than is common in movies of their sort.

Oddly enough, it’s this very intelligence that mitigates against Ride the Pink Horse, in which Montgomery portrays Lucky Gagin, a not-too-bright petty crook out for revenge against Fred Clark as a murderous Political Boss; he just never convinces us that he’s as dumb as his character is supposed to be.

Montgomery walks and talks just like a pug throughout the film, but every so often he visibly relaxes and just listens while another character talks, and in these moments his face betrays him with a perceptive, alert expression that all the Dis ’n’ Dats in his dialogue just can’t hide.

What we have here is an educated man playing a Dummy, and for all his brains, Montgomery just ain’t a good enough actor to hide it.

I should go on to add, though, that except for this, Ride the Pink Horse is just about everything you could want in a film noir and more, with moody lighting, long, expressive takes, a host of skillfully limned minor characters, and the showy stylistic flourishes one expects from this genre.

Yet even the standard film noir brutality takes an oddly thoughtful turn here: for though the Good Guys in this movie take an awful lot of physical abuse — very graphically portrayed — the Baddies get their lumps off-camera, if at all.

And this is not a small point when you’re talking about film noir. One of the staples of Classic noirs no one ever mentions is that grin of Guilty Pleasure lighting the features of Bogart, Powell, et al. as they prepare to deliver a well-deserved ass-kicking to their erstwhile tormentors.

Nothing like that ever happens in Ride the Pink Horse, as if Montgomery were trying to subtly convey that violence is, after all, the province of the Bad Guys, and we grown-ups must look elsewhere for catharsis.

Hmm. Bob Montgomery may not be the best movie-maker ever, but he maybe deserves more attention than he’s getting.

Wed 19 Oct 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

A REVIEW BY RAY O’LEARY:

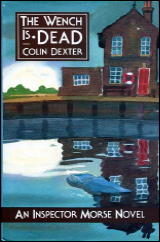

COLIN DEXTER – The Wench Is Dead. St. Martin’s Press, US, hardcover, 1990; Bantam, US, paperback, 1991. First published in the UK: Macmillan, hardcover, 1989. Reprinted many times since. TV Film: ITV/PBS; Season 11, Episode 1 of Inspector Morse in the UK. (11 November 1998), with John Thaw as Chief Inspector Morse.

Colin Dexter borrows the premise of one of the finest Mystery novels ever, despite what some may think, Josephine Tey’s The Daughter of Time, and has Inspector Morse try his hand at investigating a historical crime from his hospital bed.

This crime, however, isn’t nearly as famous as the Richard III murders, and judging by the book’s Dedication, the names of people involved in the case were changed and some of the circumstances fictionalized.

Morse, in Hospital (as they say over there) with ulcers, is given a short Vanity Press tome by the widow of its author, who was Morse’s short-lived roommate. Bored nearly to death himself, Morse reads what seems to be a straightforward account of an 1859 murder; slowly, over several days, absorbing all the facts of a case in which three Oxford canal boat crewmen were convicted of a passenger’s murder, Morse becomes convinced that there was something wrong about the case, and with the aid of Sgt. Lewis and the daughter of another patient, comes up with his own solution.

I sampled a couple of Morse novels several years ago, well before he became Hot Stuff on Mystery!, and I must admit they didn’t make much impression on me. I picked this one up for its resemblance to the Tey classic, and because the nice lady running the Library Used Book Sale kept insisting I could squeeze a few more books in my bag for the “Buck a Bagful” sale.

All I can say is I enjoyed it much more than I had expected.

Tue 18 Oct 2011

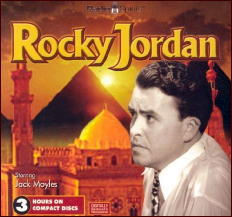

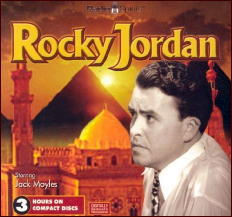

Old Time Radio’s ROCKY JORDAN (1945-1957)

by Michael Shonk

There is no simple credit line for Rocky Jordan. The radio series had many lives leaving it with a confusing history. This is an attempt to simplify that history and reveal a few surprises along the way. We begin where Rocky began:

A MAN NAMED JORDAN. Columbia Pacific Network (aka CPN or CBS West Coast). 15 minutes. Monday through Friday. January 8, 1945 through August 17, 1945. Written and directed by Ray Buffum. Jack Moyles as Rocky Jordan, Paul Frees as Ali, Jay Novello as Duke, Dorothy Lovett as Toni.

The story was told in the format of a radio serial complete with cliffhangers. With only two episodes surviving, it is difficult to judge the entire series, but one hopes the entire series was as fun and entertaining as the surviving episodes.

Set in Istanbul, the Cafe Tambourine’s owner Rocky Jordan is an adventurer who enjoys taking on bad guys in his search for profit. Rocky has little interest in the native culture and has a native Man-servant, Ali.

The two episodes feature a story of danger and adventure as Rocky seeks profit by busting a bad guy’s plan to smuggle Nazi war criminals and their loot out of Germany.

A MAN NAMED JORDAN. CPN. 30 minutes. Weekly. November 3, 1945 through September 27, 1947.

No episodes survive but it is assumed the same staff and cast returned.

ROCKY JORDAN. CPN. 30 minutes. October 31, 1948 through September 10, 1950. Produced and directed by Cliff Howard. Jack Moyles as Rocky, Jay Novello as Captain Sam Sabaaya.

Most of the episodes from this series survives.

Rocky and his Cafe Tambourine are now in Cairo. Trouble weary, Rocky tries to avoid adventure, but seems destine to always find himself stuck in the middle of trouble. Effort is put in using authentic music and locations, respect is paid to the different culture, and because of that Cairo comes alive to the listener.

The series mimics such films as Casablanca. There is a mystery to the characters. It is never revealed why Rocky can never return to America. Moyles is perfect as Rocky, while Novello as Captain Sabaaya is his equal. The relationship between the two characters was the backbone of the series’ appeal.

The next time Rocky resurfaced CBS was thinking television: “George Raft, movie actor, takes title role of CBS’s Rocky Jordan radio show tonight. It goes on TV this fall.” (Los Angeles Times, June 27, 1951)

Billboard (March 31, 1951) reports CBS plans to convert a number of their radio shows to television, including Rocky Jordan.

Broadcasting (September 10, 1951) mentions Rocky Jordan was “now in preparation” for TV.

Meanwhile, radio’s Rocky Jordan, with George Raft replacing Moyles, returned as a CBS summer series. It would be the only time Rocky would air over the entire country:

ROCKY JORDAN. CBS. June 27, 1951 through August 22 (*) 1951. Produced and directed by Cliff Howard. George Raft as Rocky Jordan, Jay Novello as Sabaaya, Four episode of the series’ eight plus the audition tape still survive.

(*) While radio logs from both the New York Times and Washington Post has Rocky‘s last episode August 22, the Los Angeles Times has an episode for August 29.

Raft plays Rocky as a tough guy with a heart of gold, making one miss the talents of Jack Moyles. Besides Raft, the only other real difference was having bartender Chris annoyingly talk directly to the listeners as he narrated the action.

There is no evidence that Raft continued to play Rocky beyond the CBS summer series. Using the Los Angeles Times logs (this post would not have been possible without JJ’s Radio Logs), I was unable to find any Rocky Jordan episode airing after August 29, 1951 and before October 13, 1952.

According to Broadcasting (October 6, 1952) Rainer Brewing signed to sponsor Rocky Jordan on CPN for fifty two weeks starting October 13, 1952.

ROCKY JORDAN. CPN. October 13, 1952 through June 26, 1953. Jack Moyles as Rocky Jordan.

None of these episodes survives. We know of Moyles’ return because Broadcasting twice (November 10, 1952 and March 30, 1953) referred to Moyles (using present tense) as starring in the title role of CPN’s Rocky Jordan.

There are surviving audition tapes from attempts to bring Rocky back in 1955 and 1957.

ROCKY JORDAN. August 25, 1955. Two fifteen minute episodes. Jack Moyles as Rocky, Jay Novello as Sabaaya.

Rocky is caught in the middle of a story of intrigue as his attempt to save a friend and Tribal leader backfires. The story is in the style of Rocky Jordan but uses the cliffhanger format of A Man Named Jordan.

ROCKY JORDAN. Armed Forces Radio Service. 1957. Jack Moyles as Rocky, Jay Novello as Sabaaya. Recreation of the episode “Nile Runs High” (September 18, 1949)

Rocky Jordan, with Jack Moyles, was a quality program with intelligence, wit, and style. This was radio at its best, telling a story with words and sounds so vivid it would awaken our imaginations and take us away to experience ancient cultures and exotic lands.

SOURCES:

JJ’s Logs: http://www.jjonz.us/RadioLogs

Thrilling Detective: https://www.thrillingdetective.com/jordan_r.html

Rand’s Esoteric OTR: http://randsesotericotr.podbean.com/category/rocky-jordan

Radio Archives: Volume 1.

Volume 2.

Volume 3.

Episodes are available to listen at archive.org and a variety of other places on the internet.

Tue 18 Oct 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[11] Comments

IT IS PURELY MY OPINION

Reviews by L. J. Roberts

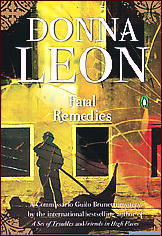

DONNA LEON – Fatal Remedies. Wm. Heinemann Ltd., UK, hardcover, 1999. Penguin, US, September 2007. Reprinted several times.

Genre: Police procedural. Leading character: Commissario Guido Brunetti; 8th in series. Setting: Italy.

First Sentence: The woman walked quietly into the empty campo.

Commissario Guido Brunetti is in a difficult position. It is his job to uphold the law. However, his wife, Professor Paola Brunetti, wants to stop a local travel agency from

running sex tours for men. She demonstrates her cause by vandalizing the agency.

With added pressure from above to solve a robbery and murder with possible Mafia connections, Brunetti is concerned both about his relationship with his wife and his career.

A book that starts without a prologue but with an unexpected, intriguing opening will always capture my interest and Leon wrote a great first chapter with Fatal Remedies.

But there are so many things to which I look forward, and enjoy, from Donna Leon. Her characters are wonderful. Brunetti has a very normal family with normal conflicts, even when they are demonstrated in not-so-normal ways.

I appreciate Brunetti’s seeming pragmatism and understanding that his job is to uphold the law, which is not always just; and the police secretary, the wonderful, smart and enigmatic Signorina Elettra is endlessly fascinating, for Brunetti as well as for the reader.

Leon creates a rich sense of place through sensory descriptions of sight, sound and particularly, smell. She also uses humor and introspection well… “There are days when I think everything’s getting worse, then there are days when I know they are. But then the sun comes out and I change my mind.â€

In spite of the light moments, Leon always reminds us that this is a true police procedural in which there is violence and tragedy. Well done, Ms. Leon.

Rating: Very Good.

Bibliographic Note: Scheduled for 2012 is number 22 in the series, Beastly Things. For a complete list, check out the Fantastic Fiction website.

Mon 17 Oct 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[7] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

H. C. BAILEY – Call Mr. Fortune. Methuen & Co. Ltd., UK, hardcover, 1920. E. P. Dutton, US, hardcover, 1921. Mckinlay Stone & Mackenzie, hardcover, 1921. Macdonald, UK, hardcover, 1949.

This is the first collection of Reginald Fortune short stories and, if the problems I had getting a copy are any indication, the scarcest one. Six stories are in this volume, and they range in quality from very good to excellent. There are, I might add, no bad or even poor Fortune short stories in any of the collections.

“The Criminal Investigation Department, solicitors, and others dealing with those experiments in social reform which are called crimes, by continually appealing to his multifarious knowledge and his all-observant eye, turned Dr. Reginald Fortune, general practitioner at Westhampton, into Mr. Fortune of Wimpole Street, specialist in — what shall we say? — the surgery of crime. And Reggie Fortune, though richer for the change, was not grateful. He liked ordinary things, and any day would have gladly bartered a murder for a case of chicken-pox. This accounts for his unequalled sanity of judgment.”

Fortune investigates usually with great reluctance and frequent complaints. In one case he says, “I believe the beggars get murdered just to bother me” and “They only do it to annoy because they know it teases.” Indeed, at one point he is “elaborating a scheme by which the murder and the cricket seasons should be conterminous.” In those cases where he willingly joins in the chase, children or friends are usually involved.

Fortune is not to everyone’s tastes. He, like most males, hasn’t really matured, only he never pretends that he has. While he is something of a gourmet, he has a penchant for sweets and muffins. He likes to play with puppets and write his own scenarios. Cold and discomfort he complains about bitterly, as would a small boy, particularly when he is taken away from his toys or his leisure, and when he drives an automobile it is with the complete abandon of youth.

Certainly even less mature, however, are Stanley Lomas of the Criminal Investigation Department and the various policemen that Fortune works with. Despite the unfailing accuracy of the Fortune eye and intellect, they continue to scout his ideas and ignore his warnings.

Read this collection, if you can find it, or any of the Fortune short story collections. Each puzzle in all of the books ranges from good to superb. And if Reggie irritates you in the beginning, as he did me when I first read him 30 years ago, you may find, as I did, that he grows upon you if he is given a chance.

— From The Poisoned Pen, Vol. 7, No. 1

(Whole #33), Fall-Winter 1987.

Editorial Comment: Bill was quite right about the price of a First Edition of this book, a “Queen’s Quorum” title — there is one currently offered for sale on ABE for $500 — but I doubt that he suspected a future in which those of you with a Kindle could have a copy zapped to you in seconds for only 99 cents.

Mon 17 Oct 2011

MARTIANS GO HOME. 1990. Randy Quaid, Margaret Colin, Anita Morris, John Philbin, Ronnie Cox. Based on the novel by Fredric Brown. Director: David Odell.

There may not be any underlying significance in what happens in this science fiction movie — it’s about an invasion of obnoxious green Martians who know everybody’s secrets, to their great rollicking delight — but there’s certainly thirty minutes worth of good laughs in their antics.

As far as how they get here, the composer of theme music for TV shows accidentally sends a message into space inviting then to cane visit our planet, and so they come — by the millions! (Truth in advertising. We see only about a dozen of them at different times on the screen — this is not a big budget movie.)

Bedrooms are not safe, the president’s office can’t keep them out, they’re all over the world; and they’re here to stay until our hero can find out a way to get rid of them. “Invaders can be dealt with. These guys are tourists!”

I think the book may have been clearer on one point, though — sorry, it’s been 30 or 40 years since I read the book – that human society exists only by maintaining secrecy and privacy and (therefore) complete dishonesty in all our affairs.

It’s a cynical point, and even though I enjoyed the movie, I think it’s one the people involved in making it let slip right through their fingers.

— Reprinted from Mystery*File 33, September 1991 (slightly revised).

[UPDATE] 10-17-11. While I was researching the credits for this movie on IMDB, I discovered that I must be one of the elite. There are perhaps only four or five people in the world who have liked this movie, and I am one of them.

It has been released as a Region Two DVD in the UK, but I’ve found a copy on VHS, and it’s on its way to me now. With Margaret Colin in it, really how bad could it be? (That’s assuming I was wrong about it the first time, which I am not conceding.)

« Previous Page — Next Page »