October 2014

Monthly Archive

Sun 12 Oct 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[26] Comments

DASHIELL HAMMETT – The Maltese Falcon. Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1930. Originally published in Black Mask magazine as a five part serial from September 1929 through January 1930. Reprinted many times, in both hardcover and paperback. Film: Warner Bros., 1931; also released as Dangerous Female (Ricardo Cortez). Also: Warner Bros., 1936, as Satan Met a Lady (Warren William as Ted Shane). Also: Warner Bros., 1941 (Humphrey Bogart).

I don’t suppose I have to convince you to read this book, do I? If you haven’t read it yet, I don’t suppose you will. Maybe I’m wrong. Maybe you’ve never gotten around to it. It would be easy to do. But remember, nobody lives forever. You’ve only got one life to live, and that’s all you’ve got.

COMMENTS:

1. The part of Sam Spade was made for Humphrey Bogart.

2. John Huston was wise to write the part of Rhea Gutman out of the screenplay.

3. Spade’s mind always seems to be several jumps ahead of the story, but Barzun and Taylor call him “repeatedly stupid.” Why?

4. Likeable, I’m not so sure he is.

— Reprinted from

The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 5, No. 3, May/June 1981.

Sun 12 Oct 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

JUKE GIRL. Warner Brothers, 1942. Ann Sheridan, Ronald Reagan, Richard Whorf, George Tobias, Gene Lockhart, Alan Hale, Betty Brewer, Howard Da Silva, Faye Emerson, Willie Best. Screenplay by A. I. Bezzerides, based on a story by Theodore Pratt. Director: Curtis Bernhardt.

Although it may not have the most compelling plot or the best action sequences, the Warner Brothers melodrama Juke Girl benefits strongly from Ann Sheridan in a starring role. She portrays a tough, streets smart juke joint dance girl in a bustling Florida farming and packing plant town. Her commitment to the smoke filled music hall life is tested when she encounters Steve Talbot (Ronald Reagan), a charming itinerant farmhand with a strong commitment to the plight of the common man.

The plot, which occasionally seems to deviate sharply from where one expects it to be heading, follows the story of two friends, Steve Talbot (Reagan) and Danny Frazier (Richard Whorf) as they arrive in Cat Tail, Florida looking for work. They soon come to learn that the small town is all but run by packing magnate Henry Madden (Gene Lockhart) and his strong man, Cully (Henry Da Silva).

Soon after arriving in town, Steve falls for Lola Mears (Ann Sheridan’s character) who is working at the town’s smoke filled juke joint. But he doesn’t fall as hard for the tyrannical Madden. In fact, he decides he’d rather work for small time tomato farmer Nick Garcos the Greek (George Tobias) than the packing plant owner.

This strains his relationship with Danny (Whorf) who wants to work for Madden. Along for the ride and trying to keep the peace is character actor Alan Hale, who portrays Yippee, one of the locals with a strong conscience.

For a time, things go okay for Steve and Lola. They help Nick ship tomatoes to market in Atlanta, and there’s even talk of their settling down together. But Lola abruptly skips out on Steve. She still doesn’t think of herself as the settling down type. Things then get even worse for poor Steve when there’s a warehouse murder, which the townsfolk blame on him.

The movie abruptly veers from a melodrama to something of a crime film. But even so the crime aspect remains a mere sideshow to the story about the relationship between Steve and Lola, two rural working class lovebirds trying to make their way in a rough and tumble world.

That said, aside from championing honest work, the film really isn’t very political. There’s no heavy-handed message here. Reagan’s character isn’t as much a labor leader as he is a guy originally from the wheat fields of Kansas who wants hardworking farmers to get a fair deal.

Juke Girl isn’t the type of film that will likely stick with you for days and weeks after you’ve watched it. But it is nevertheless an enjoyable film, far less gritty than the films noir of the late 1940s, but one that hints strongly at a world where the greedy and the unscrupulous would gladly prey on the weak.

—

Sat 11 Oct 2014

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

THE SMALL BACK ROOM. The Archers / British Lion Film Corporation, UK, 1949. Released in the US as Hour of Glory (1952). David Farrar, Kathleen Byron, Jack Hawkins, Michael Gough, Cyril Cusak, Leslie Banks, Sidney James, Robert Morley, Geoffrey Keen, Anthony Bushell, Renee Asherson. Based on the novel by Nigel Balchin. Cinematography: Christopher Challis. Written and directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressberger

The small back room of the title is in a once tony Park Lane building where myriad agencies including Professor Mair’s Research Section are situated. It’s just one of dozens of similar wartime sections belonging to no one in particular and answering to no one save a handful of civil service bureaucrats, politicians, and ministry officials, all maneuvering for influence, power, and glory. It’s 1943, and amidst the war petty politics and back stabbing still go on.

Boffin Sammy Rice (David Farrar, Black Narcissus, 300 Spartans, Meet Sexton Blake), is above all this. All he wants is to do his job, contribute, romance his girl Suzy (Kathleen Byron), and find some way to dull the pain and the shame caused by his tin leg.

He’s content to run his section and use Suzy as a vent for the anger his constant pain causes, which only makes him feel guilty and more useless. An expensive bottle of Scotch he keeps in his apartment in plain view is the one escape, not to kill the pain — neither it nor the dope the doctors give him will do that — but to make him forget. He has sworn not to touch it, though he does get drunk in a local pub owned by ex-boxer Knucksie (Sidney James). That bottle is a symbol of more than his pain, it also symbolizes the life he has bottled up in its smoky depths as well.

As the film opens Lt. Stewart (a young Michael Gough) of the bomb disposal unit arrives at Professor Mair’s section with a top secret problem soon assigned to Sammy; a booby trapped device being dropped by the Germans that has so far killed three boys and one man. It may be aimed at children to demoralize the British populace, but so far they haven’t found a live one to study, and when they do they need a man like Sammy to tell them how to handle it.

Meanwhile everything is complicated by Sammy’s problems, political back-fighting led by R. B. Waring (Jack Hawkins), the glad handing minister whose purview the section falls under, Mair’s incompetence, a soldier tech with a problematic wife (Cyril Cusak), and Suzy’s growing anger that Sammy will not stand up and fight for what he knows is right but hides behind his pain and that unopened bottle of Scotch.

The Archers of course were directors, producers, and screenwriters Michael Powell and Emeric Pressberger (The 49th Parallel, Black Narcissus, A Matter of Life and Death, The Red Shoes, to name a few classics) who adapted this version of the novel by Nigel Balchin (Mine Own Executioner and the screenplay for The Man Who Never Was), a British novelist whose works in the manner of Nevil Shute were both suspense novels as well as serious mainstream novels. This is one of his best remembered novels and a fine example of his abilities.

There’s an exceptional cast for this one, even in bit roles: Robert Morley, Geoffrey Keen, even Patrick Macnee gets a closeup if no dialogue, and Farrar, Byron, Gough, Hawkins, Cussak as a stuttering technician, Anthony Bushell as a bomb disposal officer, and Renee Asherson as a corporal assigned as stenographer to a bomb disposal unit are all outstanding. Asherson has a fine scene where she reads the last instructions dictated from the site where an officer was killed trying to defuse the bomb to Farrar who will be the next man to attempt it. It’s a thousand times more effective than filming the scene itself could have been.

Christopher Challis’s cinematography must be mentioned as well; the location shots capture much of the wildness of some of the remote regions the booby-trapped devices carry Sammy and Stewart to, as well as the claustrophobia of crowded pubs and nightclubs with blacked out lights, tiny labs in the small back rooms of the title, and without the usual scenes in bomb shelters or footage of burning London, sketching in the aura of wartime England subtly. As it likely was for most ordinary people in London and the rest of the country, the war is always a presence even when it isn’t at the forefront.

One outstanding sequence in the film is a surrealistic waking nightmare as Sammy waits for Suzy, the only person who can distract him from his pain, and must battle not only his pain, but the attraction of the bottle. As the clock ticks maddeningly, his pills fail him, and the bottle looms larger and larger until he even sees its outline in the pattern of the wallpaper, he breaks down.

It’s a nerve-wracking scene, and wrenching to watch the otherwise taciturn and stoic Farrar deteriorate before your eyes. It’s as uncomfortable as anything in The Lost Weekend and as surreal as the famous Salvador Dali sequence in Hitchcock’s Spellbound, and the shadows and light interplaying on that craggy face make some memorable impressions. There is a moment when in his pain he stamps down on the tin leg to crush the pills and the agony on his face is palpable.

It won’t take much imagination or provide much of a challenge to know Sammy will end up defusing one of the booby trapped devices, the twin of one that has already killed, and with a hell of a hangover, in a climactic scene of tension, or that doing so will decide his future and the fate of his relationship with Suzy, but that is dramatic structure and there is no way around it in book or film, even if anyone was silly enough to want one. It’s a tense scene and all involved wring every sweaty drop of fear out of it.

Neither the film nor the book is as well known here as it was in England, but if you can find the trade paperback edition I recommend both it and Balchin’s Mine Own Executioner (also an excellent film with Burgess Meredith and Kieron Moore) highly. And if you know the work of the Archers, especially of director Michael Powell, then that alone is enough to recommend the film.

And for what it’s worth Farrar was a cousin of mine, and we share the family nose, no small connection, so forgive me if I think it is one hell of a performance for an actor who a few years before was playing Sexton Blake in B films.

Fri 10 Oct 2014

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

VALENTINE WILLIAMS and DOROTHY RICE SIMS – Fog. Houghton Mifflin, hardcover, 1933; Popular Librar #76, paperback, n. d. [1946]. Film: Columbia, 1933 (starring Mary Brian, Donald Cook and Reginald Denny).

The S. S. Barbaric lives up to its name as three of its passengers are strangled en route from New York to England. The first is the irascible millionaire Alonzo Holt, who wouldn’t have sailed if he had known that the son he never knew, his estranged second wife, and the charlatan who used to conduct seances for him were aboard.

While there is an occasional good sentence — for example, “The curious delusion that the ability to amass wealth implies a disposition to distribute it in charity, deserving or undeserving, attracts shoals of beggars to the millionaire’s door” — the authors have overwritten throughout. Worse, none of the characters ring true, except for the bridge fanatic, nicknamed Sitting Bull. Still worse, the hero spots the murderer through a clue provided by the heroine, who could not possibly have been in possession of the information she gave him.

Skip this one unless you’re a real nostalgia buff.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 11, No. 3, Summer 1989.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC NOTES: This is co-author Dorothy Rice Sims only entry in Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV. Valentine Williams was a far more prolific writer of crime ad detective fiction. There is a very extensive article about him on Mike Grost’s Classic Mystery and Detection website. Highly recommended!

PostScript. It belatedly occurred to me that I had been lazy, and that I should have tried harder find out more about Mrs. Sims, if I could. It turns out that there is quite a bit more to say.

From a website dedicated to famous contract bridge players, there is a short biography of her, along with a photo. Excerpting from the first couple of paragraphs:

“Dorothy Rice Sims was born June 24, 1889 at Asbury Park NJ. From her teens, Dorothy was active in competition, holding the motorcycle speed championship for women (1911) and becoming one of the first U.S. aviatrixes, in which capacity she met and married ACBL Hall of Fame Member P. Hal Sims.

“She was a noted sculptress, painter and author in fields other than bridge, though she wrote several bridge books. She is widely credited with inventing the psychic bid, but probably initiated only the popular name for it. However, she wrote her first book on the subject, Psychic Bidding, 1932.”

Note that one of the characters that Bill mentions is a fanatic bridge player.

Thu 9 Oct 2014

THE POWELL TOUCH

by Walter Albert

In 1935 and 1936, William Powell followed his 1934 starring role in MGM’s The Thin Man with two RKO comedy-mysteries, Star of Midnight and The Ex-Mrs. Bradford, both of them directed by Stephen Roberts.

In Bradford Jean Arthur is the ex-Mrs. Bradford who turns up at the beginning of the film to have physician Bradford (Powell) served a subpoena for non-payment of alimony; in Star, Ginger Rogers is Donna Manton, a social butterfly in love with lawyer Powell who claims to have more fun solving cases than trying them and whose friends consider him to be a combination of Charlie Chan, Philo Vance and the Sphinx.

Bradford is a racetrack mystery and Star a Broadway mystery, both versions of the classic form of amateur detective considered by less-than-bright homicide detectives to be a prime suspect in a murder case.

Bradford has the more original conclusion with the suspects invited to a meeting at which a film reveals the murderer’s identity, but Star is better paced and has some more polished acting in secondary roles, particularly by Vivian Oakland as a former girlfriend of Powell’s and Gene Lockhart as a somewhat unconventional butler who didn’t do it but is drafted for some ironic sleuthing.

Arthur and Rogers, both fine actress/comediennes, are delightful foils for Powell’s stylish drollery and each has at least one scene that is a standout: Arthur in a brilliant closing sequence and Rogers in a comic tum as she foils Oakland’s play for Powell.

Powell’s earliest appearance as an urbane amateur detective was in The Canary Murder Case, in which Jean Arthur also appeared, and by 1935 there was no more adept player of drawing-room comedy-mysteries.

The actor is probably no less accomplished in Bradford and Star than he is in The Thin Man, but it is certainly debatable whether, as William Everson maintains in The Detective in Film (Citadel, 1972), The Thin Man is “almost” equaled by the two lesser known movies.

The level of craftsmanship in all three of the films is very high, but I think that the decisive elements in the superiority of The Thin Man — and in its continuing popularity — are the inspired pairing of Myrna Loy, who matches Powell’s arch style with her own elegant delivery and movement, and first-rate scripting by Albert Goodrich and Frances Hackett, and directing by W.S. Van Dyck.

Script, direction, and performance come together in an extraordinary tour-de-force that climaxes the film. The wrapup party sequence in The Thin Man still dazzles as Powell delivers what is in effect an extended monologue and it is this perfectly timed scene, a classic example of the “cosy” mystery denouement, that, for me, makes The Thin Man the success that Bradford and Star achieve only in part.

Both actresses were on the verge of major stardom when they appeared with Powell. Loy would, of course, continue the role of Nora Charles in five sequels, and also appear in films like The Great Ziegfield, The Rains Came, The Best Years of Our Lives, and Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House.

The Thin Man is usually seen as the one in which Loy escaped type casting as an Oriental temptress — most notably as the daughter of Fu Manchu in The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932) — but non-Oriental roles in films like Love Me Tonight (1932), Topaze (1933) and Manhattan Melodrama (1934) suggest that her film roles were far more varied than they are usually thought to have been.

An oddity in the casting of Arthur is that she had played in three Fu Manchu films (in 1929 and 1930) and in the early thirties was better known as an actress in melodramas than as the star of comedy/dramas as she was subsequently to be.

By an equally ironic reversal, Rogers, after her dizzying success with Fred Astaire, would establish herself as a dramatic actress in the late thirties and forties, but with Astaire and with Powell she demonstrates an apparently natural comedic talent and a freshness that makes her performances with them among her most engaging.

[Almost eighty years] after their original release dates, The Thin Man and the two “forgotten” films, Star and Bradford, are entertainments that largely defy the passage of time. In addition, all three films — and one must add to the list James Whale’s brilliant 1935 baroque send-up of the drawing-room mystery, Remember Last Night? — are a tribute to the popularity of the amateur sleuth mystery in the 1930s and to the professional and artistic integrity of this genre.

The Thin Man gains some lustre in the context of related films but also should remind us that it operated out of a tradition that still gives pleasure for its wit and invention and, in particular, celebrates the career of one of the screen’s most distinguished player of amateur detectives, William Powell.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 8, No. 5, Sept-Oct 1986.

Wed 8 Oct 2014

COLLECTING PULPS: A Memoir, Part 12 :

Rereading UNKNOWN and UNKNOWN WORLDS

by Walker Martin

Why reread? I’ve known several readers and collectors who bluntly state that they seldom or never reread stories or books. They argue that there are too many new books waiting to be read, sort of the like the old saying, “So many books, so little time.”

I love to reread but only my favorite books and stories. And only the ones that I consider to be outstanding or great. There is nothing more exasperating than to reread a book and realize that it was not even worth reading the first time. Not to mention the waste of time. That’s why I’ve always noted on a slip of paper the date read, my grade, and comments about the book. Then, decades later, I can tell at a glance what I thought of the book and whether it is worth a second reading or not.

So aside from the enjoyment of rereading an outstanding book, why read it again? Some books demand a second (and a third and a fourth) reading because they have several layers and levels of complex meaning that you might want to explore and investigate. Also a book read in your twenties may reveal additional meanings when you reread it many years later. There have been books that I read as a young man that I didn’t have the proper maturity to truly understand but as an older reader, I now find them to be indispensable.

Every reader has their favorite books that they have reread. Some of mine are:

War and Peace — 3 times.

Moby Dick — 3 times.

The Sun Also Rises — 5 times.

Under the Volcano — 5 times.

In the different genres I’ve several books that I’ve reread:

In science fiction: Alfred Bester’s The Demolished Man and Stars My Destination. Also the novels of Philip K. Dick and Robert Silverberg; the short stories of J.G. Ballard and Theodore Sturgeon.

In the detective and crime genre: the novels of Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, Elmore Leonard, and Ross Macdonald.

In the western field: the novels of Luke Short, Elmore Leonard, Elmer Kelton. Lonesome Dove is maybe the best western I’ve ever reread.

I also have reread stories in the pulp magazines. Many literary critics make the mistake of lumping all the pulps into one sub-literary category. They think all the pulps published mediocre and poor action fiction of very little redeeming literary value. They are wrong. There is such a thing as excellent pulp fiction, and I’ve tried to point out some examples in this series on collecting pulps.

Of course, I absolutely agree with Sturgeon’s Law which in simple terms may be explained as “90% of everything is crap.” This is a good thing to say to anyone who criticizes your tastes in reading matter. For instance if they sneer at your love for detective, SF, or western fiction, then you can state Sturgeon’s Law, which I’ve found to roughly apply to just about all forms of literary endeavor.

In other words, I’m always looking for that less than 10% that I hope will be worth reading and rereading. As I reread my notes spread throughout thousands of books and fiction magazines, I see I’m now at a good point in my life where I’m reading mainly the good 10%. Sure, every now and then I make a mistake or blunder and find myself reading the 90% crap, but after so many years of reading, I’m getting pretty good at avoiding the stuff that is not worth reading.

A couple months before the August Pulpfest convention, one of the committee members, knowing my love for the magazine Unknown, asked me if I would participate on a panel discussing the title. This made me think about Unknown and how I had started collecting and reading it so many years ago.

When I first started to think about collecting it, I was just a teenager and had very little money. I had enough to buy the SF digests and paperbacks but a set of Unknown back in the 1950’s cost around $50, a sum that I never had until years later. Back then, just about all pulps were a dollar or less, a fact that is hard to believe now.

Finally in 1963, while attending college, I managed to put aside $50 and I started scouting around for a set of the 39 issues. All I could pay was $50 but everyone I contacted wanted more. I even contacted the Werewolf Bookshop in Verona, Pennsylvania (this bookstore advertised in many of the digest SF magazines) and I still have the letter dated September 3, 1963. I stapled it into my Unknown book where I noted my thoughts and comments on the magazine. The owner stated that he had contacted three fans and only one was willing to sell and he wanted $200 for his set.

Back in 1963 this was an outrageous sum, and it’s lucky I did not send money to the Werewolf Bookshop. It seems the owner was in the habit of sending you anything he had if he did not have the books that you ordered. Then when you complained about receiving books that you didn’t want, he would ignore your letters and keep your money. If I had sent him $200, there is no telling what he would have shipped me. Except that it would not have been a set of Unknown. I have read about and even met fellow collectors who fell victim to this scam.

Fortunately, I eventually bought a set from Gerry de la Ree, a SF collector and dealer who lived in New Jersey. For decades in the 1960’s, 1970’s, 1980’s, Gerry mailed out monthly sale lists listing SF pulps, digests, books, and artwork. He wanted only $50 and I now had the complete set. I read several stories in scattered issues, but college and then being drafted into the army delayed my project of reading the complete set.

However, by 1969 I was discharged and I spent six months of doing nothing but reading. I didn’t even look for a job, and I loved living in my mother’s house drinking beer and reading all day. She must of thought she raised a bum, but she was wrong. She raised a book collector and reader.

I started reading from the first issue, March 1939 and I read each issue, every story, every word, until the end in October 1943. That’s 4 1/2 years and 39 issues. Over 250 stories ranging from novel length to short story. John W. Campbell, the editor of both Unknown and Astounding, estimated that the 7 by 10 inch pulp size issues contained 70,000 words of fiction and the 8 1/2 by 11 inch format contained 110,000 words.

That means I read over 3 million words of fiction in 1969 when I started my project of reading the entire set. I forget how long it took me but since I was not wasting any time working, I probably read close to an issue every day or two. I then recorded my thoughts in a standard English composition notebook. I think they still make these things, black with white speckles and it says “Composition” on the front cover. With over 100 pages I could devote two pages to each issue, listing each story and author along with a grade and my comments. At the end of each year, I did a summary listing my favorites.

During the Pulpfest panel, I read some of my comments from this notebook and a couple collectors asked me if I had such books for each magazine that I collected. I used to but I eventually switched to the system of putting a slip of paper in each magazine or book with my comments, grade, and date read. I have thousands of books and magazines with these annotations tucked inside each copy. I still have a few of the notebooks, with the Unknown comments being the most extensive. I see I have one on Weird Tales where I read and noted my reactions to reading three years of issues, 1933-1935.

So to prepare for the panel, I reread only the stories that received an outstanding rating back in 1969. We often think that we were a different person 45 years ago and for the most part we probably were. I was in my twenties back then and ahead of me were all the usual things like getting married, raising a family, starting a career, buying houses, etc. Of course this series of essays deal with my collecting experiences. So what did I think at the age of 72 looking back on my younger self praising and exclaiming over the stories in Unknown?

As I reread story after story, I was impressed again at the literary quality of the magazine. I guess that’s why I’m writing about the magazine again in 2014, only instead of just comments meant for my older self, I’m now writing for other collectors and readers and encouraging them to read and reread Unknown.

What were the outstanding novels? Lest Darkness Fall and The Wheels of If by L. Sprague de Camp, who also wrote the superior Harold Shea novels with Fletcher Pratt. Death’s Deputy and Fear by L. Ron Hubbard; Hell Is Forever by Alfred Bester; Conjure Wife by Fritz Leiber; None But Lucifer by H. L .Gold and de Camp.

Among the shorter fiction, we have several novelettes by Henry Kuttner. I believe these stories represent the first quality fiction by Kuttner. Jane Rice also had several stories and when the magazine died in 1943, she almost stopped writing because Unknown was her favorite market. One of the sad things about Unknown ceasing publication was the fact the Jane Rice had a 33,000 word short novel that was scheduled for a future issue. But the manuscript has been lost by Street & Smith and Rice did not keep a copy. Anthony Boucher, Fritz Leiber, and Theodore Sturgeon also had many shorts.

But despite all the excellent fiction in Unknown, the magazine can best be described and explained by simply looking at the art of Edd Cartier. He is Unknownwith its gnomes, demons, and fantasy figures that defy description. I once had a chance to buy an original Unknown cover painting by Cartier. In the 1980’s, someone was walking around one of the Pulpcon conventions with the painting but he wanted $2,000 for it. At the time I had bought many cover paintings but the highest price I ever had to pay was $400. One of my collector mistakes. I should have dug up the money somehow because it’s worth a fortune now.

Cartier dropped out of fantasy and SF illustration sometime in the early fifties but I did manage to meet him around 1990 at Pulpcon in Wayne, NJ. Rusty Hevelin was running Pulpcon and he said Edd Cartier would be available to talk to one night. But it would be for only a special group of pulp collectors who Rusty would choose. Fortunately, I was one of them and it remains a Pulpcon highlight that I still remember all these years later.

Speaking of Cartier brings up what I think of as one of John W. Campbell’s mistakes. With the July 1940 issue the cover art was discontinued. Campbell must have looking to attract more readers with a literary style cover showing a more bland, sedate listing of stories. Maybe he thought the illustrations too garish on the covers. But the lack of any cover art at all just made the magazine seem a puzzle to many newsstand browsers. One of the big reasons for cover art is to grab your attention while you are looking at scores of magazines. Without cover illustrations the magazine just was lost on the stands. Where do you put it? This experiment was tried by previous pulps like Adventure and The Popular Magazine, and it was never successful.

I’ve owned several sets of Unknown during the last 50 years and it is still possible to pick up issues. After the panel a couple collectors told me they wanted to start collecting it and I told them to keep looking through the dealer’s room at Pulpfest because I saw several issues for sale. Usually the price is around $20 but I’ve seen higher and lower prices. Ebay also has issues.

At present I own two sets, one is the usual individual 39 issues and one is a bound set in 14 hardcover volumes. There is an interesting story about this bound set. I only paid $400 for it at Pulpcon a few years ago and neither the dealer or me noticed that it had a signature in the first volume. When I got home I was amazed to realize that I had John W. Campbell’s personal bound set of the magazine. It was inscribed as follows, “To George Scithers, who worked hard for this set”. Signed John W. Campbell. I’ve worked hard for certain sets of magazines, so I know what he means.

The magazine is not really rare because so many SF and fantasy collectors loved the magazine and saved their copies. It is probably the most missed of all the pulp titles. In the letter columns of old SF magazines, it is often referred to as “the late, lamented Unknown.” For several years after it ceased publication due to the war time paper restrictions, letters in Astounding kept asking when the title would be revived. Evidently Campbell intended to start it up again when paper was available. But that was not until 1948 and then Street & Smith killed off all their pulps except for Astounding in 1949.

So Unknown remained dead but several magazines were influenced in the 1950’s. Fantasy Fiction lasted four issues in 1953; Beyond Fantasy Fiction lasted ten issues in 1953-1955; and The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, which is still being published, has often printed Unknown type fiction.

If you are not a collector but you still want to read some of the best fiction, there are several collections available:

UNKNOWN WORLDS: Tales From Beyond, edited by Stanley Schmidt and Martin H. Greenberg (Garland Books, 1988) This is the biggest and best collection. 25 stories and 517 pages.

RIVALS OF WEIRD TALES, edited by Weinberg, Dziemianowicz, and Greenberg. (Bonanza Books, 1990) Among stories from other magazines, there is a section of 11 stories from Unknown, amounting to 200 pages.

THE UNKNOWN, edited by D. R. Bensen (Pyramid, 1963) This paperback has 11 stories and story notes.

THE UNKNOWN FIVE, edited by D.R. Bensen (Pyramid, 1964) Another collection from Bensen.

UNKNOWN, edited by Stanley Schmidt (Baen Books, 1988) Nine of the longer stories and 304 pages. Paperback.

HELL HATH FURY, edited by George Hay (Neville Spearman Ltd., 1963) Seven stories in hardback.

OUT OF THE UNKNOWN, by A.E. Van Vogt and E. Mayne Hull (Powell Publications, 1969) This paperback has seven Unknown stories by Van Vogt and wife.

And finally there are two full-length studies of the magazine:

THE ANNOTATED GUIDE TO UNKNOWN AND UNKNOWN WORLDS, by Stefan R. Dziemianowicz (Starmont House, 1991) This is an excellent study of all aspects of the great magazine. A total of 212 pages with a long essay about the magazine, followed with detailed story annotations on every story, a story index, an author index and much more! Highly Recommended.

ONCE THERE WAS A MAGAZINE, by Fred Smith (Beccon Publications, 2002). Each issue is discussed plus author and title index.

So ends my rereading of Unknown and I hope to return someday. I guess we shall never see a revival of the magazine. I noted over a dozen pleas from readers in Astounding, all asking when Unknown would be revived, but the October 1943 issue was the last one. A digest issue was planned and discussed in the October issue but an order for additional paper reduction came and Unknown was a victim of WW II.

REST IN PEACE: Unknown and Unknown Worlds.

NOTE: To access earlier installments of Walker’s memoirs about his life as a pup collector, go first to this blog’s home page (link at the far upper left), then use the search box found somewhere down the right side. Use either “Walker Martin” or “Collecting Pulps” in quotes, and that should do it.

Tue 7 Oct 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

THE VIRGINIAN. Paramount, 1946. Joel McCrea, Brian Donlevy, Sonny Tufts, Barbara Britton, Fay Bainter, Tom Tully. Based on the novel by Owen Wister. Director: Stuart Gilmore.

The Virginian has many of the elements one would expect to find in a solid Western that, all things considered, stands the test of time. This postwar film adaptation of Owen Wister’s 1904 iconic tale of the Old West has romance, a dastardly villain, cattle rustling, a genteel New England woman adapting to life on the frontier, and a friendship strained by one man’s poor decisions.

Directed by Stuart Gilmore, who is perhaps better known by cineastes for his editing work, The Virginian stars Joel McCrea in one of his earlier Western features. He portrays a man simply known as “The Virginian,†a Wyoming cowhand originally from the Old Dominion who is making a new life for himself out West. He’s playful and stoic, laconic and willing to speak his mind. The Virginian isn’t a man of formal education, yet he has a solid grasp on the way of the world. And he knows the difference between right and wrong.

The plot isn’t particularly complex. But it doesn’t need to be. It’s 1885, and a Bennington, Vermont, schoolteacher by the name of Molly Wood (Barbara Britton) is restless. She simply doesn’t want to get married and stay put in that small New England town. So she decides to take a train to Wyoming, where she plans to work as a teacher.

Soon upon arriving out West, Molly encounters two cowhands, the overly enthusiastic Steve Andrews (Sonny Tufts) and The Virginian (McCrea). In a plot device not unusual for Westerns, the story’s primary male and female protagonists, Molly Wood and The Virginian, don’t exactly start their relationship off on the best foot. But it’s the palpable tension between the characters that allows the story to move forward.

The Virginian is also a story about friendship in a society where law and order have yet to be firmly established. The Virginian and Steve Andrews have seemingly known each other for a long time. They have worked and gone drinking together. When Steve falls in with a cattle rustler named Trampas (a well cast Brian Donlevy), the two men’s friendship comes under great strain. The Virginian may be a bit of a prankster, but he won’t abide cattle rustling.

The Virginian repeatedly warns Steve against allying himself with the devious Trampas, but his protests are repeatedly ignored. It’s a fatal mistake for Steve, whose hanging at the hands of The Virginian, although it occurs off screen, is nevertheless poignant. There’s a beautifully sad bird song that accompanies the hanging. It’s a truly haunting moment.

Although The Virginian doesn’t have much in the way of particularly unique cinematography, it does make very good use of color to convey meaning. Early on in the film, Molly sports a bonnet with lavender feathers on top. These blend seamlessly with the couches and curtains of a saloon front room, demonstrating that she fits in more with the domestic, more sedate part of the saloon, than with the rowdy bar area.

There’s also a scene in which the conflict between The Virginian and Steve is foreshadowed. Both men are standing at the bar, drinks in hand. They are discussing Steve’s plan to get to New York City and to leave the cowhand life behind him. The Virginian bets his friend that he’ll never make it to the Eastern metropolis. In the background during this whole scene, although visible only briefly at the beginning, is a decanter of an unknown bright red liquid. It’s noticeably out of place, even at a bar. The symbolism is clear. There will be blood between these two friends.

Trampas is also a study in color. He has a dark heart and he wears it on his sleeve. Literally. He’s one color from head to toe, including a black hat and a black gun belt. The contrast between The Virginian and Trampas is best seen in the famous scene in which The Virginian presses his gun into Trampas’s gut and says, “When you call me that, smile.†In every way, The Virginian is of a lighter hue than the villainous cattle thief.

In conclusion, The Virginian, even if not worthy of critical acclaim, remains worth a look. In some ways, it’s a somewhat mature Western for its time. There are no goofy sidekicks or saloon girls. It’s as much a study of human nature as it is a frontier tale. Best of all, McCrea demonstrates that he is a natural in the saddle. No wonder why his career flourished as he went on to make so many fine Westerns.

Mon 6 Oct 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

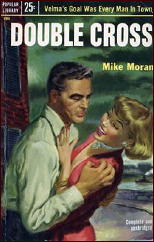

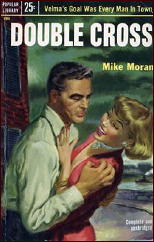

MIKE MORAN – Double Cross. Popular Library 494, paperback original, April 1953.

A recent review on this blog of William Ard’s Hell Is a City produced some opposing opinions on his work, but neither the review or his discussion brought up the fact that Mike Moran was one of Ard’s pen names. (Ben Kerr was mentioned, while Thomas Wills was also not.)

This was Ard’s only use of Mike Moran as a name to hide behind — for what reason he or someone thought he needed one is a question for which no one living may know the answer — and while I have some good things to say about it, I also have to admit that it’s a wildly uneven piece of work.

Tom Doran is the PI who tells the story. He’s an independent operator, but when the head of the agency he sometimes works for sends a case his way, he’s happy to take it. He’s hired to be a bodyguard for a boxer whose sparring partners have all been frightened off the job while the fellow and his trainer are in training camp preparing for a big fight.

Besides an ugly cook who takes a decidedly bad attitude toward Doran, there are two beautiful women involved, the first the boxer’s live-in girl friend Velma, a would-be singer with the morals of a bunny rabbit; the second, the blonde who owns the farm where the entourage has set up camp. Her name is Janet Pearce, and before you know it, she and Doran have taken up housekeeping together.

It’s that kind of PI story. The opening scene is very tentatively written, and even when the actions of the cook are explained later on, they still don’t make a lot of sense. Nor do those of any of the bad guys, were you to sit down and try to do so, as I am invariably wont to do, even for inexpensive PI fiction, as this one was when it first came out.

On the other hand, once the characters are introduced and the story is well on its way, it’s smoothly told and very easy to finish in a mere two hours or less. (It helps that it’s only 128 pages long, a mere bagatelle by today’s standards.)

Mon 6 Oct 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

DOUGLAS PRESTON & LINCOLN CHILD – The Pendergast Trilogy:

1. Fever Dream. Grand Central Publishing, hardcover, May 2010. Vision, paperback, April 2011.

2. Cold Vengeance. Grand Central, hardcover, August 2011; paperback, February 2012.

3. Two Graves. Grand Central, hardcover, December 2012; paperback, July 2013.

These three books by bestselling writing team Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child (Relic, The Ice Limit, Gideon’s Sword) comprise the first trilogy within the series that features the brilliant, wealthy, and eccentric FBI agent, Aloysius Pendergast. Previously Special Agent Pendergast and his friend Lieutenant Vincent D’Acosta of New York homicide appeared in a number of stand alone books including Relic/Reliquary and Dance of Death/Book of the Dead which were tied together. The second duo consisted of Pendergast’s battle with his mad brother Diogenes, a master criminal.

That name, Diogenes, should be a clue to Pendergast’s origins, because he is very much a Sherlockian figure (in Wheel of Darkness he even travels to Tibet with his student Constance), given to keeping his own council, brilliant deductions, and epic battles with his own Moriarity.

That said, these are not properly mystery novels and certainly not detective stories. They are pulp nonsense on a high level, and Pendergast is less Holmesian than a more literate and literary Richard Wentworth or Lamont Cranston, replete with his mysterious Brownstone lair Bruce Wayne might envy.

We’re in the country of Frank Packard’s Jimmie Dale, the Gray Seal here, or even Zorro and the Scarlet Pimpernel. The devil is in the details, and the details are for, all the trappings, these are not mystery novels half so much as apocalyptic pulp adventure that Lester Dent or Norvel Page would have recognized as such. The books have a sort of dream-like logic of their own and frequently stray into quasi-science fiction and the supernatural with the same casual verve of the pulps of the past.

Beginning in Fever Dream we learn that twelve years ago Pendergast’s beloved wife Helen was killed in a hunting accident in Africa on their honeymoon and that Pendergast blames himself. When he discovers Helen was murdered, he sets out for revenge leading to the swamps of Mississippi and a madman cursed with a disease that renders him hypersensitive to life, thanks to forbidden experiments begun by Nazi doctors before WWII.

Cold Vengeance finds Pendergast discovering his greatest ally, his bother-in-law Judson Estrhazy, may in reality be Helen’s murderer, and to an even more shocking revelation that Helen isn’t dead at all. As he probes the conspiracy swirling about him he moves from Scotland to the bayous of Louisiana and to Central Park where Helen is swept from his arms just as he is about to be reunited.

Two Graves finds Pendergast very nearly destroyed by his obsessive hunt, withdrawn from his closest friends and allies, pitted against a diabolical serial killer, and about to solve a mystery he would be better off never solving as his adventure carries him to dense South American jungles and a revelation about Helen and himself that will shock him to his core.

I won’t give more away though you will likely beat Pendergast to the final revelations by at least two and a half books. I am surprised though that it is done this well, considering that elements of the plot weren’t all that new when Ira Levin wrote The Boys From Brazil. They do manage to tie all three books rather neatly into a whole though, which I would have thought impossible for anyone else.

Half the fun of these is that Preston and Child do get away with things that you wouldn’t allow a lesser writer because they are literate, playful, fun, and inventive (in Brimstone the villain is Wilkie Collins’s Count Fosco, no less).

All their books, together and separately, are fun, and I confess the non series Ice Limit and Riptide had some extremely clever ideas in them I wish I had used. Even their novels on their own are highly entertaining, and Preston’s non-fiction Dinosaurs in the Attic about his years at the New York Museum of Natural History is a delightful memoir.

It’s rare to find anyone this literate, or with their dry wit on the bestseller lists these days. They know exactly what they are doing and do it well. Dumas would have admired Pendergast’s prison break in Dance of Death; Relic is a modern classic and was a terrific film (minus Pendergast but with Tom Sizemore as D’Acosta), though I don’t think most of the Pendergast books would work all that well on screen; and A Cabinet of Curiosities a rare serial killer novel that thrills as much as it intrigues.

In addition they have created their own little world with characters from other novels appearing in the Pendergast series, with most recently one of the protagonists of Ice Limit showing up in the new Gideon series. If you have ever wondered what Walter Gibson or Norvel Page might have done given the time to polish and play with their apocalyptic adventures these might at least give you an idea.

Enter this world with willing suspension of disbelief set on high and you are in for high concept entertainment done in a grand guignol style and at least a shadow of Holmesian panache if not detective skills.

In the right mood and mind set, these are probably the best bang for your buck you will find on recent bestselling bookshelves. These deliver as much as the back copy reviews promise and more.

Sun 5 Oct 2014

RAY HOGAN – Outlaw’s Empire. Doubleday “Double D Western,” hardcover, 1986. Signet, paperback reprint, January 1987.

Since Ray Hogan is a fellow who has written more than a hundred westerns, I’ll put off discussing his career until another time. He is a fellow who started out in paperback, however, beginning with Ex-Marshal published by Ace in 1956, but he didn’t make it into hardcover until Jackman’s Wolf (Doubleday) in 1970.

From the little I know of his work, I would characterize it as being in the realistic vein, workmanlike and solid, and that’s a decent description of Outlaw’s Empire too, with only a few quibbles. One of them being the title, which seems to have little to do with the book, and the cover of the paperback, which is extremely nice, but it also does not have much to do with the book.

Which is primarily a chronicle of the adventures of Riley Tabor, a wandering cowpoke who teams up with a fellow heading west in a grand army wagon, the fellow also being a grand womanizer – anything young in skirts – and therefore being considerably needful of having someone team up with him.

Quoting from page 23:

“Bad business fooling around with another man’s wife. You make a habit of it?â€

“Every chance I get,†Hale said promptly. “I believe in taking care of all women – married or single – as long as they’re willing, and most are. Spent most of my life working hard. No time for anything but work and study. Then I lost my intended wife in a fire. That changed my way of thinking. Figured life was just too uncertain, so now I pluck my roses whenever the opportunity presents itself – and so far it has been fairly often.â€

“That rancher back in Dodge just about ended all that for you–â€

“No doubt about that, and I’ll be eternally grateful to you for showing up when you did.â€

Riley made no comment.

Adam Hale’s life does end quickly, and in very strange fashion, leaving Riley with Hale’s wagon as well as everything else he owned — his rig, his horses, and all of his personal belongings – along with a huge surprise. A surprise big enough that I cannot tell you about it, given the possibility that by either chance or happenstance you find yourself reading this book someday. Suffice it to say that unearned surprises have a way of catching up with you, and that’s what this mostly amiable but somewhat rambling novel, full of interesting people, is all about – building your house on sand.

Or deciding not to, as the case may be. Not that Riley really has a good deal of leeway either way in the matter, which is perhaps why his story does not turn out all that badly in the end.

— Reprinted from Durn Tootin’ #7 , July

2005 (slightly revised).

[UPDATE] 10-05-14. Not having any other choice, but definitely wanting to show you the cover of the paperback edition, what I had to do was to take the black-and-white photo I’d included in that issue of Durn Tootin’ and colorize it into a monochrome facsimile of the real thing.

I also note that I was being so careful about not revealing anything about the big surprise I referred to that I have no idea now what it (and the book itself) was all about. I seem to have liked it, though.

« Previous Page — Next Page »