Fri 3 Jun 2011

THE CASES OF EDDIE DRAKE – PART ONE, by Michael Shonk.

Posted by Steve under Old Time Radio , Reviews , TV mysteries[6] Comments

A Review by Michael Shonk

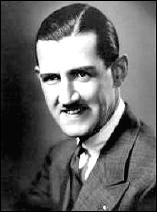

THE CASES OF EDDIE DRAKE. TV series. Thirteen 30 minute episodes. Created and written by Jason James (Jo Eisinger). Cast: Eddie Drake: Don Haggerty, Dr. Karen Gayle: Patricia Morison (nine episodes), Dr. Joan Wright: Lynne Roberts (four episodes), Lt. Walsh: Theodore Von Eltz. Produced by Harlan Thompson and Herbert L. Strock. Directed by Paul Garrison.

Eddie Drake was your typical hardboiled PI of the time, from his attitude to his roving eye for anything in a skirt. Eddie shared the details of his cases with beautiful Dr. Karen Gayle, perhaps television’s first psychologist. She was writing a book about criminal behavior and wanted the point of view of a hardboiled PI. After nine episodes, Dr. Joan Wright replaced Dr. Gayle.

The Cases of Eddie Drake began on radio as The Cases of Mr. Ace. George Raft was New York PI Eddie Ace who each week sat down and told Dr. Gayle about his latest case.

Note that the film Mr. Ace (1946) starring George Raft as political kingmaker Eddie Ace had no connection to the radio series.

The relationship between Ace/Drake and Doctor Gayle was different in the radio and television versions. On radio, Dr. Gayle makes it plain she is willing to get personal, while Ace has problems asking her out for dinner. On TV, Drake does everything but chase her around the desk.

The body count was high for both Ace and Drake. Dr. Gayle once noted Eddie’s cases were full of “heaters and cadavers.” Of the three surviving radio stories, Eddie’s cases all ended in gunfire and nearly everyone dead.

Behind both series was Jason James, Edgar award winner (with Bob Tallman for the radio series Adventures of Sam Spade in 1947). Heavily influenced by the writings of Dashiell Hammett, the scripts for Ace and Drake never came close to the quality of James’ work on Spade. But then, Raft and Haggerty were no Duff or Bogart.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————–

THE CASES OF MR. ACE. Radio. Syndicated. Aired June 4, 1947 through September 3, 1947 on WNEW-New York (*). Paragon Radio Production. 30 minutes. Cast: Eddie Ace: George Raft. Written, directed and produced by Jason James (Jo Eisinger).

“Key to a Booby Trap,” June 4, 1947 (aka “Key to Death”)

Tough guy Ace meets Dr. Gayle and tells her about his latest case. A Frenchman confesses to Ace he killed a man who was bothering his wife. He pays Ace to give a key to his lawyer. The lawyer says the Frenchman is innocent, but his wife is eager to watch her husband die. When the key leads to more death, Ace wants to know why.

“Man Named Judas,” June 25, 1947 (aka “Lost Package”)

Ace is hired to deliver a package but fails. When he returns, he finds the client dead. Then third-rate versions of Cairo and Gutman (Maltese Falcon) arrive wanting the last surviving Judas coin.

“Watch and the Music Box”

Only the last half survives. Script was reused as the Eddie Drake episode, “Shoot The Works”.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————–

One episode of Eddie Drake remains available to be viewed on the internet or DVD.

“Shoot the Works.” (First aired date unknown.)

Drake tells Dr. Gayle about his recent case. A woman hires Drake to get her watch back. It had been stolen during a gambling club robbery where a man was killed. She had been with a man who was not her husband, and she is worried, if the police recover the watch, her husband will find out.

Drake visits the club owner, a wild Russian “Prince” who is desperate for Drake to find the woman he loves, a woman he has only seen on a nickel peep show. The bodies begin to pile up when the thief arranges to sell the watch to Drake.

After the story, Eddie takes the beautiful Doctor out for drinks. There the actors break character and tell the audience the episode’s credits.

Much like other syndicated TV Film programs of the time, Eddie Drake was nothing special beyond mildly entertaining. Eddie was a character who was interchangeable with the countless other hardboiled PIs of the time.

The creative idea of a psychologist using the point of view of a hardboiled PI for a book about criminal behavior was wasted as a weak framing device to tell typical hardboiled mysteries. The acting was professional but average, never adding anything new or of depth to the characters or stories. The only truly unforgettable part of Eddie Drake was “Dave,” Eddie’s new car, a three-wheel 1948 Davis Divan.

Which leads us to Part Two, coming soon: “The Mysteries of the Making of The Cases of Eddie Drake.”

Common knowledge about the TV series today is that CBS filmed nine episodes in 1949 and then never aired it. DuMont is supposed to have filmed the final four episodes and broadcast all thirteen in the period from March 6 to May 29, 1952. Before that, according to one source, NBC aired the series between June 4, 1951 through August 27, 1951 (13 weeks).

Did CBS shelve the series for three years? Why did Lynne Roberts replace Patricia Morison after nine episodes? Why would DuMont film the final four episodes then wait six months to show it? When did Eddie Drake first air, 1949 or 1951? How much of what is currently believed about this series wrong?

SOURCES:

Billboard archives available for free reading at Google e-bookstore.

Episodes of The Cases of Eddie Ace are available to listen to at various sites on the internet. I did my listening at Internet Archives (archive.org)

(*) New York Times radio logs can be found at www.jjonz.us/RadioLogs

The television episode “Shoot the Works“ is also available around the internet and on DVD, Best of TV Detectives – 150 episodes. I watched it at Internet Archives and Classic Television Archives (which also has an episode log).

http://www.archive.org/details/The CasesOf EddieDrake-ShootTheWorks1949

http://ctva.biz/US/Crime/EddieDrake.htm