Thu 13 Apr 2023

A British TV Series Review by David Vineyard: THE GOLD ROBBERS (1969).

Posted by Steve under Reviews , TV mysteries[4] Comments

THE GOLD ROBBERS. London Weekend TV, 1969; 13 episodes. Peter Vaughan, Richard Leech, Arto Morris, Maria Aitken, Louise Pajo, Fred Bartman, Peter Copely Guests: George Cole, Ian Hendry, Patrick Allen, Roy Dotrice et al. Produced by John Hawkesworth.

When five million pounds sterling being flown into the United Kingdom by the failing government of a Middle Eastern state is met by a highly organized criminal team and stolen, an international manhunt is set off led by Detective Chief Superintendent John Craddock (Peter Vaughan) of Scotland Yard and Detective Sergeant Tommy Thomas (Arto Morris), an effort that will put their careers and lives at risk.

The Gold Robbers is a thirteen episode closed crime series that was remarkably dark, violent, and dour for British television of its time. It marked and early part for reliable character actor Vaughan in a rare lead as an all to human but doggedly intelligent policeman. It highlighted as well a number of British stars like Ian Hendry, Patrick Allen, Roy Dotrice, and others as individuals involved in the complex heist that leads Craddock across Europe and into the worlds of high finance, international banking, smelting gold, and politics. It was where high finance and society met low crime and criminals before the downbeat and not wholly resolved conclusion.

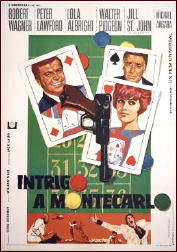

Filmed in black and white, this one is well worth catching, marked by intelligent scripts and naturalistic acting. In each episode Craddock and his team focus on some element of the heist, a driver, gunman, crooked air traffic controller, mercenary soldier and their families and loved ones while closing in on slimy crooked casino owner Victor Anderson (Frederick Bartman) who ran the operation for an unknown Mr. Big.

Along the way, Craddock’s relationship with his son and his mistress fall apart while he is taken under the wing of charming wealthy newspaper and airline magnate Richard Bolt (Richard Leech), whose airline flew the hijacked gold into the UK.

The ruthless gang uses money, threats, and murder to protect itself as Craddock tightens the noose, despite setbacks and maddening interference from his superior the Assistant Commissioner (Peter Copely) that gets worse as Craddock closes in on the men behind the crime including some in the government.

Characters weave in and out of the series, some suspects temporarily get away, some are brutally killed before they can talk, and all the time Craddock’s career is threatened as much by success as failure.

You can currently find the entire series on YouTube (Nostalgia channel), and it is worth watching for its gritty realism, tough minded characters, sharp writing, and increasingly complex plot that builds to a satisfying downbeat ending that ties all the plot threads while leaving somethings open. It is basically a thirteen part serialized story though, minus cliffhangers and with each episode self contained.

Among those contributing to the scripts are producer John Hawkesworth, spy novelist Berkley Mather (co-writer of the screenplay for Dr. No), and Allan Prior (Softly Softly: Taskforce and novels).

The Gold Robbers is plotted more like a really good police procedural novel than a television series with character arcs for police and crooks, and a sense of the cost and the allure of crime. Vaughan’s Craddock is a flawed but compelling protagonist. The series holds up well and has a good mix of suspense, detection, police work, crime, and romance (even with a bit of nudity; it is British television) as the plot unfolds through the characters and not just around them.