Tue 5 Feb 2013

Reviewed by Dan Stumpf (Book/Film): THE UNDYING MONSTER (1922/1942)

Posted by Steve under Horror movies , Reviews[6] Comments

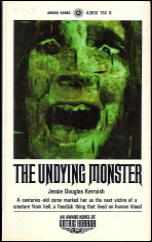

JESSIE DOUGLAS KERRUISH – The Undying Monster. Heath Cranton, UK, hardcover, 1922. Macmillan, US, hardcover, 1936. Reprinted in Famous Fantastic Mysteries, June 1946. Award A351S, paperback, 1968. Lulu Press, POD softcover, 2013.

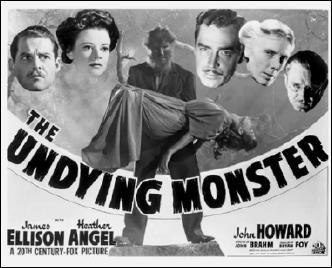

THE UNDYING MONSTER. 20th Century Fox, 1942. James Ellison, Heather Angel, John Howard, Bramwell Fletcher, Heather Thatcher, Aubrey Mather. Director: John Brahm.

The Undying Monster by Jessie Douglas Kerruish was first published in England in 1922 and is considered by some a classic tale of lycanthropy. I considered it a wanton squandering of my precious youth, but there you are. Thinking back, there were probably some inventive bits in the tale, but for me they were ruined by…. But I can’t yet tell you why. Read on:

Undying starts out promisingly with a family curse, murder in the moonlight and all sorts of delicious Victorian nastiness. It seems that the Hammand family (local gentry with an imposing manor house and a coat of arms that goes back to the Flood) is periodically stalked from time to time by a horrendous but unseen thing that rips some of them limb from limb and scares others into gibbering madness.

Good so far. But when Oliver Hammand, latest in line to inherit the family unpleasantness, encounters the thing in the dark, he gets off with a few bites and a case of amnesia while his companion is mauled to near death and his loyal dog is spread all over the countryside. Naturally concerned, Oliver’s sister calls in female paranormal investigator Luna Bartendale, and that’s when things get gummy.

Luna Bartendale is probably the most irritating character ever consigned to printed page. She hasn’t been on the case for more than a few paragraphs before she’s saying things like, “I have some theories but I won’t discuss them until….†and then “This confirms what I was thinking but before I say more I must…..†followed by “I know why, but I can’t reveal it to you yet,†and “There’s a very good reason why I can’t tell it to you.â€

Now I got nothing, against foreshadowing, but a man gets tired of that kind of talk all the time. No one likes the guy who says “I told you so,†but even worse is one who says “I could tell you so — if I felt like it,†and Luna Bartendale, for all her groundbreaking appearance as fiction’s first female paranormal detective, says very little else. By the time the plot reached the point where Good and Evil were locked in what should have been a horrific struggle, I was hoping merely that the superannuated boogeyman of the title would gobble her up but (SPOILER ALERT!) no such luck.

All the sadder then that there are glimmerings of a good story here. So good in fact that 20th Century Fox made a movie of it in 1942 — kind of. Writer Lillie Hayward and Michael Jacoby replaced the annoying Ms Bartendale with cowboy star James Ellison playing a Scotland Yard investigator — and doing it surprisingly well.

He’s aided by Heather Thatcher as a plucky distaff-Watson, but his attentions are focused primarily on Heather Angel as the distraught sister of poor Oliver Hammond (They changed the spelling for reasons best known to themselves.) played by John Howard, who had already been paired with Miss Angel in the Bulldog Drummond series over at Paramount.

Undying Monster is a stylish affair, thanks largely to director John Brahm, who brought similar gothic elegance to The Lodger (1944) and Hangover Square (1945) and cinematographer Lucien Ballard, who will be remembered for The Wild Bunch. Together they impart an atmosphere not unlike the Sherlock Holmes series over at Universal, with evocative fog, looming shadows, and a general sense of mystery — rudely dissipated when we finally see the rather unprepossessing monster.

And I should add a bit of trivia beloved of bad-movie buffs: the opening shot of Undying Monster is repeated exactly in a later, cheaper Monogram film, Face of Marble (1946). Understandable, since Michael Jacoby, who toiled at or near Hollywood’s bottom rung for his whole career, worked on both films. But one wonders with what weary desperation poor Jacoby found himself re-typing his own work in such reduced circumstances.