Mon 25 Jun 2012

Characters from DFW #13: HUGO OAKES, LAWYER-DETECTIVE — by Monte Herridge.

Posted by Steve under Bibliographies, Lists & Checklists , Characters , Columns , Pulp Fiction[9] Comments

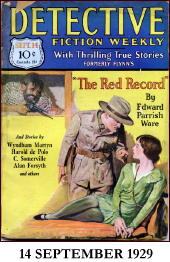

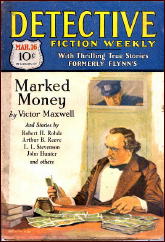

DETECTIVE FICTION WEEKLY

by Monte Herridge

#13. HUGO OAKES, LAWYER-DETECTIVE, by J. Lane Linklater.

One of the precursors of Erle Stanley Gardner’s series character Perry Mason the attorney, the Hugo Oakes series is fairly entertaining. J. Lane Linklater created this series about a criminal defense attorney who solved crimes. He appeared in twenty stories in Detective Fiction Weekly from 1929-1934, a respectable run.

J. Lane Linklater was the pseudonym of Alex Watkins (1893?-1983?). He had two other series that also ran in the magazine: Sad Sam Salter (1937), and Paul C. Pitt, a kind of conman (1936-1941).

One of the stories describes Oakes the person: “Hugo Oakes, lawyer, investigator, gruff friend of the penniless in trouble, had four great interests in life. Those interests were law, detection, people—and horses.†(Finishing Touches)

A physical description of Oakes is noted in another story: “He was a wizard with flowery eloquence, too, but outside of the courtroom it didn’t seem to go with his age-colored, shapeless clothes, his casual manner, his pudgy person.†(You Think of Everything)

He wears a slouch hat, and rolls his own cigarettes. Very little information is given about Oakes’ background and upbringing. There is a mention by Oakes himself on one occasion that he liked horses because he grew up on a farm (Not One Clew).

He prefers to use ungrammatical, common speech that belies his education. However, when he wishes he can use much better language. Inspector Mallory prefers Oakes to use common language; he “liked Oakes much less when the lawyer used four-syllable words.†(Arsenic in the Cocktail)

Oakes is not one of the high-priced lawyers with a fancy office and furniture. He has a shabby office that costs him twenty dollars a month, and often doesn’t have enough in his business accounts to pay that. His only employee is Mamie, who is his combination stenographer-bookkeeper-secretary.

The reason he has very little money is that people rarely paid him for the legal work he did for them. Oakes has a thriving practice helping people with little money out of trouble. He did his own detective work rather than hire a detective agency to do it for him. However, we must remember that these stories take place during the Depression, when many people either lacked jobs or had poorly paying ones.

Oakes is an egalitarian, preferring regular people and the poor to the better off and wealthy classes. A person’s lack of money never affected Oakes’ decision to take them on as a client.

The only other regular in the series is police Inspector Mallory, who is usually glad to have Oakes help on his cases, but “he would never admit it. They might gibe and grouch at each other on occasion, but Mallory had intelligence enough to recognize the value of Oakes’s assistance, and Oakes was always willing to let the credit go to Mallory.†(Finishing Touches)

Each story usually involves Oaks being called in by a client and then having to solve a murder, usually to save the client. Once his client was a murder victim before Oakes could reach the scene. Inspector Mallory was always on hand at the scene of the crime. Mallory either does not understand what is going on, or seeks the simplest explanation (always wrong, of course).

Very rarely did Mallory actively ask for Oakes’ help on a case. One special case was in the story “A Pair of Shoesâ€, where Mallory asked for assistance. A rich businessman had disappeared, and three weeks of work had led Mallory to be desperate enough to ask for unofficial help. Oakes gets to work and very quickly solves the case in a logical manner.

Another request for help from Mallory led to a murder investigation by Oakes at a high society horse show in “Not One Clewâ€. Oakes said he did not care for society, but he did like the horses. Part of the deal with Mallory was a free ticket to the horse show.

Another off-beat story for the series is “Crazy People Are Smart,†where Oakes accepts the challenge of a prison chaplain and investigates an old murder. Bill Tubby had just twenty-four hours before his scheduled electric chair execution for a crime he claimed he did not commit. Inspector Mallory had solved the case to his satisfaction, and he is afraid Oakes will do something to change the outcome. Oakes goes to the scene of the crime and investigates, coming up with an unusual solution that saves Tubby.

Hugo Oakes has a system for locating the murderer in crime situations: “Always look for the type of mind capable of conceiving and executing the particular crime under scrutiny.†(The Wild Man From Borneo)

Inspector Mallory knows about this system, and in this story attempts to use it himself. Unfortunately he chooses the wrong person as the murderer, and Oakes has to straighten him out. This is one case where Oakes becomes involved because the victim was a friend of his. Oakes is uncharacteristically not in his usual cheerful mood; in fact he is angry and unsmiling.

Another story gives a bit more of Oakes’ insight into crime detecting: “But a man always leaves the imprint of his personality on his crime. What a man does is the expression of what he is. He may not leave fingerprints, but he always leaves mind prints.†(Crazy People Are Smart)

So Hugo Oakes is a believer in the application of psychology to crime-solving. The stories contain little violence, though one exception is in the story “Finishing Touches.†Here Oakes confronts the guilty party and has Inspector Mallory secretly back him up, which is needed when the murderer attempts to kill Oakes. Mallory wounds the murderer and saves Oakes’ life.

The series is interesting to read, although there are not any great criminal masterminds, fancy destructive gadgets, or gangs of criminals running around. It took all kinds of stories in the pulp era, and this series is better than many other series in DFW.

The Hugo Oakes series, by J. Lane Linklayer:

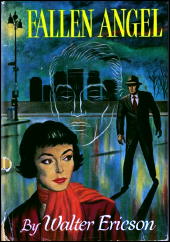

Hello, Jim! September 7, 1929

Court Costs Saved October 5, 1929

The Wild Man From Borneo February 22, 1930

The Watchful Woman May 10, 1930

Not One Clew May 24, 1930

Crazy People Are Smart May 31, 1930

The Seventh Green Murder July 26, 1930

The Lady Confesses August 23, 1930

Three Old Crows October 18, 1930

A Pair of Shoes November 15, 1930

Finishing Touches January 3, 1931

You Think of Things February 7, 1931

Women Always Mean Trouble March 28, 1931

Arsenic in the Cocktail April 4, 1931

He Died Laughing July 4, 1931

Murder Next Door September 5, 1931

Find the Silencer October 10, 1931

The Second Floor Murder November 19, 1932

The Dead Client December 2, 1933

On the Brink June 2, 1934

Biographical sketch of Linklater from the March 16, 1929 issue of Detective Fiction Weekly:

HERE is a personal greeting from J. Lane Linklater, author of “One O’Clock in the Morning,” in this issue. We asked him to stand up and say a few words to you:

You can’t mean me, cap’n?

Oh, well—

We’ll avoid the statistical as far as possible and get down to the vital.

I have lived more or less decidedly and existed more or less uncertainly, in Washington, Oregon, California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and Louisiana; that is, down the Pacific Coast from British Columbia to the Mexican border, and across the south to Louisiana. Thus it will be seen that I have never set foot on any but a coast or border State.

I have held down — sometimes for a very brief period — forty-three jobs, in offices, restaurants, hotels, boarding houses, and again in offices; in large cities, small towns, construction and logging camps, in green valleys and desert plains. If I was working in a town, it was never far away from a restaurant; if in a camp, it was never very far away from the cookhouse.

Incidentally, the transition from job to job was at times sudden and drastic. On one occasion, for instance, I was night porter in a “coffee and” dump, and a week later I was head bookkeeper for a chain store system some two thousand miles away. Honestly — or perhaps I should say, actually — I am a very fair bookkeeper.

While I’m on the question of jobs — and what is more important? — I might add that the last regular job I had, and the one I was on longer than any of the others, was as editor of a farm paper. I was never better fitted for any job than for this one inasmuch as I had never in my life touched my hand to a plow and couldn’t tell the difference between a Jersey heifer and a Shorthorn bull. Now I know what a Shorthorn bull is, having met one in a dissatisfied mood.

Among the people I have met and become friendly with — and this is vital, from the point of view of both life and letters — were bankers, labor agitators, gamblers, ministers, politicians, hoboes, Chinese cooks, mining-stock promoters, hard-working bohunks, and waitresses. Of these I should say that the bohunks were the most useful, the hoboes the happiest, the Chinese cooks the most successful, and the waitresses the most interesting — to me.

Perhaps the most accurate indication of the kind of life a man has led is where he has slept. Well, I have slept in very expensive hotels — when I was working there — in middle-class hotels, in cheap hotels, and in fifteen-cent flophouses; also in bunk houses, ditches, city parks, fields, woods and swamps. Of these I should say that the woods were the most comfortable and the flophouses the most interesting.

I have never been arrested. This I now regret exceedingly. I have had several opportunities, although I never offended society very seriously, except by going broke. I have been accosted on the street around three o’clock in the morning in San Francisco, Los Angeles and New Orleans and other minor municipalities which suspected that my financial status warranted my arrest as a vagrant. Their suspicions were correct, but I was always able to convince them otherwise. As I say, I now regret it. I may yet overcome this disadvantage.

In these emergencies my tongue was assisted by my face, a deceptively mild arrangement that never seemed to fit the role of roving mendicant. I have been mistaken for a well-known Methodist minister in Portland, Oregon, and for a Chatauqua lecturer in Sweetwater, Texas.

My formal education, unfortunately, was not very extensive. However, I have read rather incessantly, if not systematically. Meditating upon what I had seen and what I had read I decided, about a year and a half ago, to forsake the discussion of ton litters and live stock diseases for the production of fiction. I inquired about it. I read the writers’ journals. I asked advice of people who know about these things — I was always keen for advice.

They all told me to hang on to my job for five or perhaps ten years, the while I tried to write fiction. I thereupon quit my job cold. Advice is fine, but I have always thought that if you’re going to do a thing, the thing to do is to go ahead and do it, sink or swim. I’m not rich yet, but the wife and I are going back down to California for the winter.

I have never been well enough to undertake anything violent, and never sick enough to take to my bed. It is a condition that presages a long life. Under the head of more good luck, I have a wife — acquired about eight years ago — who is a good scout and a smart woman; a father and mother, both alive and well, who are intelligent and good natured—they had to be to put up with me—and a number of friends who stick through the years.

All of these things count. Not that it matters, but I am now thirty-six years old.

Previously in this series:

1. SHAMUS MAGUIRE, by Stanley Day.

2. HAPPY McGONIGLE, by Paul Allenby.

3. ARTY BEELE, by Ruth & Alexander Wilson.

4. COLIN HAIG, by H. Bedford-Jones.

5. SECRET AGENT GEORGE DEVRITE, by Tom Curry.

6. BATTLE McKIM, by Edward Parrish Ware.

7. TUG NORTON by Edward Parrish Ware.

8. CANDID JONES by Richard Sale.

9. THE PATENT LEATHER KID, by Erle Stanley Gardner.

10. OSCAR VAN DUYVEN & PIERRE LEMASSE, by Robert Brennan.

11. INSPECTOR FRAYNE, by Harold de Polo.

12. INDIAN JOHN SEATTLE, by Charles Alexander.