July 2009

Monthly Archive

Mon 6 Jul 2009

There are certain posts for which the comments that follow take on a life of their own. Take for example a short piece called “An Early Example of NERO WOLFE on TV?” There are 15 comments following, which is rather high but not unusually so. But if you take into consideration that this piece was a continuation of one of Mike Nevins’ columns, to which 18 comments were added, you will realize that the subject matter — that of which actor played what well-known mystery character, or should have, struck a nerve of one kind or another.

All of which means little, in the more practical side of things, except the final (or most recent) comment on the second post was from Mike Doran, who mentioned something I’d never known about before. Which is certainly not news in that regard, but perhaps if you missed it, you’d like to know about it, too.

Mike said, and I quote:

“… I’ve got to pass along something I came across by accident last night. It seems that MEtoo, a local station here in Chicago (digital Ch 26.3), is starting to show

Kraft Mystery/Suspense Theater episodes as part of their “Sunday Afternoon Whodunits.”

“They began this past Sunday with a 1963 show called ‘Shadow Of A Man.’ I taped it, intending to watch it sometime in the indeterminate future. Lap dissolve to last night, and I’m looking through some of my old TV Guide‘s from this period, and lo and behold, there’s the listing for this episode — which, it seems, is Revue’s attempt to turn Double Indemnity into a TV series.

“Honest — Jack Kelly plays Walter Neff and Broderick Crawford plays Barton Keyes, and those are the names of the characters. Both the TV Guide Close-Up listing and the NBC ad play up the connection, although I don’t recall seeing James M. Cain’s name in either place — or for that matter in the credits of the show (which I still haven’t watched all the way through).

“Every time I go through these old magazines I seem to stumble on something unexpected like this, and I’ve had them a long time now. This is where I get most of the nickel knowledge I put in these posts, and I’m eternally grateful for having a place like this to put it.”

And not too long ago, Mike emailed me to say, after I pleaded him unmercifully for some follow-up information:

“Well, I finally got around to watching ‘Shadow Of A Man’ yesterday. But first things first: it occurred to me that I hadn’t checked my reference books on unsold TV pilots yet, so I did. Turns out that ‘Shadow Of A Man,’ aka ‘Double Indemnity — The Series’ was in both of them.

“Back to the show itself: Nothing really special here; I’m guessing that the series would have been cases investigated by Neff the smartass ladies’ man and solved by the older, crustier Keyes — and if this sounds like a whole bunch of other shows we’ve been discussing here lately — well, if coincidences didn’t happen, we wouldn’t need a word for them, would we?

“James M. Cain’s name appeared nowhere, nor did those of Raymond Chandler or Billy Wilder.

“One other oddity: although based on a Paramount picture, this was an MCA-Universal show. I believe this has something to do with MCA’s purchase of Paramount’s film library for TV release in the ’50s; apparently there were riders to the deal, such as remake or adaptation rights.

“I remember that that ‘Going My Way’ was done on TV a couple of years before, with Gene Kelly and Leo G. Carroll in the Crosby and Fitzgerald roles. Paramount movie, MCA series. Someone with a bigger library and a better memory than mine might be able to come up with a longer list of these.”

All I can say is that I wish I lived in the Chicago area. There’s no station around here that plays anything nearly as interesting as reruns of Kraft Mystery/Suspense Theater.

Sun 5 Jul 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[11] Comments

VAN WYCK MASON – The Singapore Exile Murders. Pocket 129, paperback reprint; 1st printing, December 1941. Hardcover edition: Doubleday Crime Club, 1st printing, June 1939. Hardcover reprint: Sun Dial Press, June 1940.

Widely respected for his historical fiction, Van Wyck Mason (1901-1978) is equally if not better known for his roughly two dozen book length adventures of Captain Hugh North, a American agent working for a government outfit called G-2. The first of the latter was Seeds of Murder (1930), the last being The Deadly Orbit Mission (1968).

A complete list of all Mason’s books can be found on his Wikipedia page, along with a photo and a short biography.

Thirty-eight years is a long time to be writing spy fiction, a run that I suspect few authors can match. The setting of The Singapore Exile Murders is obvious, I should think, and the date of publication (1939) is just as important — the entire city is on edge with news of the seemingly unavoidable oncoming war streaming in non-stop from Europe.

One of the more important characters in the book is suspected by being an agent for the Japanese, and the local Japanese fleet is decidedly on maneuvers, but Hitler and the events ongoing in France, Hyde Park and Czechoslovakia seem to be causing the most jitters.

From page 155 of the Pocket edition:

Portents of increasing tension hung still heavier in the air. Police in silent and watchful squads of four stalked along streets eddying with a restless, polyglot crowd. On the horizon in the direction of Tanglin and the Naval Base, searchlights played, raking the hot, starry sky with tenuous, silver fingers. Newsboys, hoarse with excitement, rushed about waving extras printed in English, Chinese, Malay and Sanskrit. Before glaring clusters of naked electric bulbs illuminating native shops, dark-faced men argued and gesticulated. Lights glowed, too, in the official offices in the Fullerton building, and quantities of chit coolies ran errands as if the devil were after them.

A lively disquiet filled North. What the devil could be going on at the other end of the cables and the radio stations? Of only one thing was he sure: The breath of war beat hot on Singapore.

Here’s another sample of Mason’s writing, this time from page 163. This scene takes place at the home of a wealthy Dutch resident of Singapore, and one of the men and women most interested in the formula for a new lightweight metal alloy that Leonard Melville, the man everyone is looking for, has discovered:

For many years Cornelis Barentse’s

rijst-taffel would remain in Hugh North’s memory as an outstanding gastronomic triumph. The company, brilliant and pleasantly stimulated, were twenty-two in number. They ranged themselves in comfortable armchairs the length of a long table glowing with sea roses and orchids of half-a-dozen varieties.

Barentse’s huge dining room was lavishly but tastefully decorated in Javanese mode. Intricately carved ceiling beams gleamed with gold leaf; faces hideous and comic looked down from scarlet-and-gilt corbels supporting them.

Malay weapons — tulwars, pikes, krises, shields and daggers — with filigrees of gold and silver were arranged in a panoply along one wall. Small censers dangled from the four corners of the room and expelled lazy spirals of fragrant smoke. Huge lamps of bronze filigree cast on the diners an ample light which was very flattering to the complexions of the women. Dozens of candles drew flashes from the gleaming silver service, and many crystal glasses were arranged in groups before each place.

Of course there beautiful women involved — two of them, in fact — and North has to balance his own search for Melville between them. (There would have been a third, but she dies early on in the book, in what was for me quite an disturbing turn of events, but I think it was Mason’s way of letting the reader know not to take anything for granted.)

North himself is very much an earlier generation’s James Bond, US style, without the same license to kill, but perhaps it was an authorization that was purely tacit. In a similar sense, he’s an agent who’s pretty much left on his own, a la Edward S. Aarons’s Sam Durell, with lots of exotic locales included in fine detail. (See above.)

After a fairly tense few opening chapters, as North’s plane is forced down in a horrendous storm somewhere en route to Singapore, the middle portion of the book is a textbook example of how to fill lots of pages with action and twist after twist without anything actually being accomplished.

The ending is a considerable improvement in comparison, but to me, the grand finale was still rather flat — not pancake style, to make a totally inappropriate simile — but neither did it push the overall effort over the top. About average, then, overall, with parts of this eve of World War II spy adventure novel that are far better than that.

Sun 5 Jul 2009

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

I was nine years old in 1952 when my parents bought their first TV set. Being a little young at the time, I never watched what was perhaps the leading crime-drama anthology series of the early Fifties, CBS-TV’s Suspense, which had been heard on radio for almost a dozen years and debuted on the small screen early in 1949.

Just recently, however, I’ve begun to catch up, thanks to the release of three DVD sets containing several dozen episodes, including some of the earliest.

One of these, “Help Wanted” (June 14, 1949), was based on “The Cat’s-Paw,” the second published short story of the soon to be legendary Stanley Ellin (1916-1986),which had just appeared in the June 1949 issue of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine.

A few evenings ago I ran this episode and then re-read the story. Both deal with a middle-aged unemployed loner named Crabtree to whom an anonymous party offers $50 a week (a generous salary in those days) to sit in a tiny office on the top floor of a skyscraper, eight hours a day six days a week, and compile useless financial reports.

Later Crabtree’s benefactor pays him a visit and offers him life tenure, as it were, if he’ll push his next visitor out the office window. Here is where Ellin and the writers of the TV version (Mary Orr and Reginald Denham) part company. In the story Crabtree follows through, although offstage (because Ellin almost never shows an act of violence), and gets away with it because his employer has made the death look like suicide.

On the air, whose censors looked askance at unpunished crimes, the visitor falls out of the window accidentally because of his paranoid fear of the office cat, and the intended murder is impliedly brought home to Crabtree’s Iago because the victim was the wrong man, not a blackmailer but a harmless crackpot soliciting money for a campaign to bring back Prohibition.

Otto Kruger played Crabtree, and Douglas Clark-Smith, who gives the impression of having been drunk on camera, was “Mr. X”.

This live drama, directed by Robert Stevens, was the first of at least fifteen live or filmed TV adaptations of Ellin stories. The same tale, translated to film with the same title and a script based on this one, later became the basis of an episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents (April 1, 1956), with John Qualen and Lorne Greene in the roles of Crabtree and his employer and James Neilson directing.

Also on Disc One of Collection One from Suspense is “The Murderer” (October 25, 1949), based on Joel Townsley Rogers’ often anthologized short story of the same name (Saturday Evening Post, November 23, 1946).

The story begins just after dawn on a lonely meadow, probably in the same general area where so much of Rogers’ powerful suspense novel The Red Right Hand (1945) was set. Farmer John Bantreagh discovers the dead body of his sluttish wife, knocked unconscious and then deliberately run over by a car.

Then deputy Roy Clade drives up, and the dialogue between the men heightens our suspicion that Bantreagh himself is the murderer. These two are the only onstage characters in Rogers’ story.

In the Suspense version, directed by Robert Stevens from a Joseph Hayes teleplay, Jeffrey Lynn and John McQuade played Bantreagh and Clade but there are also several other characters who in Rogers’ story were only referred to in the dialogue.

This tale was never adapted for Alfred Hitchcock Presents but did become the basis of a later live version on ABC’s Star Tonight (March 17, 1955), with Bantreagh and Clade played by Charles Aidman and Buster Crabbe.

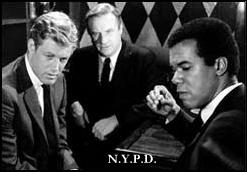

During my three years at NYU Law School I watched very little TV, but in the fall of 1967, when I was still living in Greenwich Village and waiting for the results of the bar exam (yes, I passed), a new series debuted on ABC which, with its tension and its reflection of the turbulence of the Vietnam and Black Power years and its abundant action scenes shot on the streets of New York, captivated me instantly.

N.Y.P.D., starring Jack Warden as tough detective lieutenant Mike Haines, Robert Hooks as black plainclothesman Jeff Ward and Frank Converse as newbie Johnny Corso, was directed and scripted for the most part by veterans of the golden age of live teledrama and lasted two full seasons.

Looking over the cast lists recently, I was amazed at the number of actors then based in New York who appeared in one or more episodes and went on to household-name recognition and in some cases superstardom.

In alphabetical order and limiting myself to males: John Cazale, James Coco, William Devane, Charles Durning, Robert Forster, Vincent Gardenia, Charles Grodin, Moses Gunn, James Earl Jones, Harvey Keitel, Tony LoBianco, Laurence Luckinbill, Al Pacino, Andy Robinson, Mitchell Ryan, Roy Scheider, Martin Sheen, Jon Voight, Sam Waterston, Fritz Weaver.

Fewer female cast members made it big, but among those that did were Jill Clayburgh, Blythe Danner and Nancy Marchand.

None of these names were familiar to me 40-odd years ago except James Earl Jones, whom I’d seen in an off-off-Broadway production of Othello, but today they’re instantly recognizable by millions. Why this superb series hasn’t been revived on DVD is a mystery; the fact that it hasn’t is a shame.

Speaking of vintage TV cop shows, M Squad, starring Lee Marvin, is now available on DVD, the complete 115-episode series for around $120. That’s pretty steep even if you buy the set with a 40% Borders Rewards discount coupon, but many who were teens during its first run as I was will be sorely tempted.

Sun 5 Jul 2009

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

MILTON K. OZAKI – The Dummy Murder Case. Graphic Books #33; paperback original; 1st printing, 1951.

As part of Professor Caldwell’s class in psychology, the Professor plans a visual presentation to instruct perceptual responses. Instead of the usual classroom show, a rather comlex presentation is given to the class outdoors:

Two friends of the Professor’s assistant, Bendy, stage a mock murder, with a young lady being shot at the end of a, pier and falling into the water. A mannequin has already been sunk at on the spot. The police, with prior arrangement, are to come and drag for the body.

Instead of finding the mannequin, the draggers recover the body of a young woman with her throat slit. The police report to Caldwell that the woman had no visible means of support — and no visible person to support her — and has in her apartment a room equipped like the wrapping department of a store, with paper from several first-class establishments and totally empty boxes already wrapped.

If there were no other reason for him to investigate, this puzzle would bring Caldwell into the case, despite the objections of Bendy, who knows he will have to do all the work while the Professor does the thinking.

There are enough coincidences in the novel to keep a reader muttering, “It’s a small world,” or maybe even “It’s an infinitesimal world.” Only an interest in the explanation for the wrapped empty boxes kept me reading to the end.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 10, No. 3, Summer 1988.

EDITORIAL COMMENT. An homage to Milton K. Ozaki’s prose style, along with a complete checklist of all his mystery fiction, can be found here on the primary Mystery*File website.

A longer profile on Mr. Ozaki himself can be found here, where it is said: “Even though he was the product of a mixed marriage, we believe that Milton K. Ozaki is among the earliest mystery writers of Japanese heritage writing in English as his (or her) primary language.”

Sat 4 Jul 2009

RED MOUNTAIN. Paramount, 1951. Alan Ladd, Lizabeth Scott, Arthur Kennedy, John Ireland, Jay Silverheels, Francis McDonald. Director: William Dieterle.

There’s no doubt in the world that Alan Ladd is the star of this movie. As soon as he first sets foot on screen, you get the feeling that the eyes of everyone in the theater are on him — or they would be if you were in a theater and not watching the film alone with a DVD and the TV set in your bedroom.

This is so, even with a co-star such as the beautifully sad-eyed Lizabeth Scott as Chris, the woman in the movie who’s torn between Lane Waldron (Arthur Kennedy), wanted for a murder he didn’t commit, and Captain Brett Sherwood (Alan Ladd), an officer of the Confederate Army about to join up with General William Quantrill (John Ireland), the man responsible for wiping out Chris’s parents back in Kansas.

So Brett Sherwood has a big job ahead of him, but as quiet-spoken as he is, and as conflicted as he is between what he sees as his duty (fighting for South) and what he recognizes as evil (Quantrill’s plans for taking over the entire western United States, with the aid of renegade Native American tribes), he’s up to the task.

Even Lane Waldron sees that attraction between Brett and the woman he was going to marry is futile, even over Chris’s protestations to the contrary.

The scenery is wonderful — a mountain standing almost vertically against an achingly blue sky — and in color, even more spectacular. (It’s a shame that the only images I can show you are in black and white.)

The story neither quite as wonderful or spectacular, even with a fast and furious final battle scene, with a rousing musical overture in the background as the Cavalry as usual comes riding in to the rescue. (Lane and Chris have been held prisoner, he with a broken leg, by Quantrill in a cave in what must be Red Mountain.)

But it’s the Quantrill end of the story that’s the less interesting. Watching (and listening to) Alan Ladd, as he allows Brett Sherwood grow as a character several ways at once, unable to deny his attraction to Chris while becoming more and more disenchanted with Quantrill, is worth the price of admission, as if — as I said earlier in the first paragraph these comments — there were any doubt.

The presence of Lizabeth Scott, a queen of noir films, if ever there was one, is only icing on the cake.

Sat 4 Jul 2009

ROBERT B. PARKER – The Judas Goat. Houghton Mifflin, hardcover, 1978. Reprinted many times, both in hardcover and soft.

Another book in the hard-boiled Spenser series is always more than welcome. Promised Land, the one just preceding this one, won a great deal of critical acclaim, including an Edgar award, but in spite of extraordinarily good writing, it was noticeably thin on plot, and in many ways it was largely an introspective character study of the tough Boston private eye named Spenser, and the world around him.

As if to compensate, this time the pace is fast and bloody, regenerating the series completely by means of extreme violence. A gang of terrorists wipes out most of a wealthy industrialist’s family, and Spenser is hired to track them down. After a cleansing process of this ferocity, digging out those responsible, we can only look forward to what’s in store for the future — and, no, Spenser’s proven that he’s not yet too old for this sort of thing.

Not a perfect book, but then again, so few are.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 3, May-June 1979.

[UPDATE] 07-04-09. More often than not, I’ve been revising these old reviews slightly, not to change my opinion — not ever — but to correct small typos, to change some wording around and — every once in a while — to clarify points that I’ve thought I expressed poorly the first time.

This one I decided to leave exactly as it first appeared, except for the letter grade I assigned to each book back then, which I haven’t using at all in the reprint appearances of these reviews. I gave this one an “A,” so I obviously I enjoyed it, even though the plot as I described it, I have to admit, I don’t remember very much, if at all.

Over the past few years, Robert B. Parker and I have been drifting apart. It’s not his doing, and it’s not for a lack of appreciation of my part. I think he’s a terrific writer, and for a long time, he was one of a small grouping of authors, less than only five of them, whose books I bought in hardcover as soon as they came out.

I mention this because the flaws that many friends of mine keep pointing out to me in his work, I see them too. I guess they (the flaws) bother them (my friends) more than they do me.

So why haven’t I read any of his Spenser books recently? Why have I never read a Jesse Stone novel? Or one of the Sunny Randall books?

He just seems to be writing books faster than I can read them, that’s about the only excuse I can think of, and what’s really amazing is that he’s going to be 77 this year. Unbelievable.

It’s time, I think, to make time in the day to read another Spenser novel or two, and maybe even some of those with his other characters. I think that in the 1970s and 80s, Robert B. Parker almost single-handedly saved the PI novel from extinction. I really do.

Fri 3 Jul 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[7] Comments

MIGNON G. EBERHART – Woman on the Roof.

Paperback reprint: Popular Library; several printings, including 1968, 1973. Hardcover editions: Random House, US, 1967; Collins Crime Club, UK, 1968. Hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, 3-in-1 edition, January 1968.

Mignon Eberhart’s started out by writing detective stories, more or less. Her first five books, starting with The Patient in Room 18 in 1929, featured the mystery-solving duo of nurse Sarah Keate and private eye Lance O’Leary, and they were highly regarded enough that all five were made into movies.

Allow me to digress, if you will. I did some investigation, and here’s a complete list of all the films that have been based on Eberhart novels. I’ve underlined the ones mentioned above as being the first five Keate and O’Leary books.

●

While the Patient Slept, 1935; Aline MacMahon & Guy Kibbee (Keate & O’Leary).

● The White Cockatoo, 1935; Jean Muir & Ricardo Cortez (no series characters).

● Murder by an Aristocrat, 1936; Marguerite Churchill & Lyle Talbot (the former as Sally Keating, but no Lance O’Leary).

● The Murder of Dr. Harrigan, 1936; Kay Linaker & Ricardo Cortez (the former as Sally Keating, but no Lance O’Leary; based on From This Dark Stairway).

● The Great Hospital Mystery, 1937; Sally Blane, Thomas Beck, Jane Darwell (the latter as Miss Keats, with no Lance O’Leary; based on an unidentified story).

● The Dark Stairway, 1938. (British movie also based on From This Dark Stairway, but with neither Sarah Keate or Lance O’Leary).

● Mystery House, 1938; Ann Sheridan & Dick Purcell (Keate & O’Leary; based on The Mystery of Hunting’s End).

● The Patient in Room 18, 1938; Ann Sheridan & Patric Knowles (Keate & O’Leary).

● Three’s a Crowd, 1945; Pamela Blake & Charles Gordon (no series characters; based on Hasty Wedding).

There was one book in which only Sarah Keate appeared and which did not become a movie, and that was Wolf in Man’s Clothing, which was published in 1942.

Over the years I may have seen one or two others in this list, but the only one I remember watching is The Patient in Room 18. And you can, in fact, read my review of this it here, posted earlier on this blog. I enjoyed it, but it was in spite of all of the movie’s flaws, including being played primarily for laughs.

Eberhart’s final mystery was Three Days for Emeralds, which came out in 1988, when the author was in her late 80’s. She died in 1996, with well over 50 novels to her credit.

From the book at hand, however, try the following first line on for size: “There were times when the shadow on the terrace seemed to take on the shape of a woman’s body flung down, left in its blood and beauty.”

It’s a pretty good indication, I think, of the kind of book you’re going to get when you read it. As it happens, the first wife of Susan Desart’s new husband had been murdered on that very same penthouse terrace five winters and four summers earlier. Ssusan had married Marcus when the Jim, the man she really loved — and still mourns for — died in Viet Nam.

And other than that one single reference, this is a book that could have just as easily have been written in the 1940s. It’s an old-fashioned mystery story in which the staging creaks once in a while, but when Jim turns up not dead after all, and Marcus refuses any discussion of a divorce, revealing his true nature in surprisingly violent fashion, old-fashioned chills started to creep up and down this still rather modern spine of mine.

In her later years Eberhart wrote what’s probably best described as romantic suspense, perhaps, but this is no cozy. There’s some real emotion involved in this book. I’d cast Edward G. Robinson and Barbara Stanwyck in two of the parts, and maybe John Payne as the other.

But why it was never made into a movie, nor any other of Mignon Eberhart’s books after 1945, I can’t tell you. Woman on the Roof came along too late, but if her 1940s and 50s books are as good as this one is — and I think they are — then I’d have thought that they’d have fit right in with the Film Noir era.

At the least, based on what Hollywood did to The Patient in Room 18, they would turned out better than the movies based on her early detective fiction. If ever an opportunity was missed, this was it.

Fri 3 Jul 2009

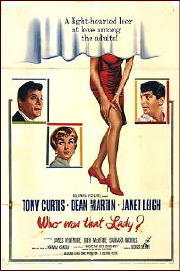

A MOVIE REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

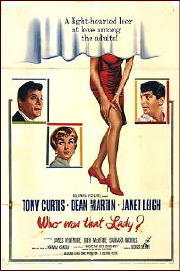

WHO WAS THAT LADY? Columbia, 1960. Tony Curtis, Janet Leigh, Dean Martin, James Whitmore, John McIntire, Barbara Nichols, Joi Lansing, Simon Oakland, Larry Storch. Screenplay: Norman Krasna, based on his play. Director: George Sidney.

Some days nothing goes right.

It’s one of those days for Tony Curtis, who teaches chemistry at Columbia in New York. A beautiful student waltzes in to thank him for a make-up test, and gets a little over enthusiastic just as his wife, Janet Leigh comes in. Janet stomps out, and Tony is in hot water. All over a make-up test.

All this is shown in the opening titles without a word of dialogue. It doesn’t really need dialogue. We get the point immediately, and the title song, catchily sung by Dean Martin fills us in on anything else we don’t know.

This is a sex farce, American screwball style.

So what would you do? Well, you probably wouldn’t call your overly imaginative bachelor buddy Dean Martin who writes for television and has a wonderfully twisted imagination.

How does Curtis explain his innocent kiss? Why of course, tell your wife you are a an FBI agent and the student was a foreign exchange student and a spy. You even go to CBS where Dean works and have FBI badges made and guns from the prop department.

Just what any sensible husband would do.

Of course, whenever the prop department at CBS makes a phony FBI badge, they notify the Bureau so it lands on local agent-in-charge John McIntire’s desk, and he passes it on to weary James Whitmore.

Meanwhile Dean and Tony have sprung the story on Janet, who is one of her less bright moments buys the story. (In fairness almost no one in this film is an intellectual giant.) Dean, though, has plans. He has a date with a sister act of exotic dancers — Barbara Nichols and Joi Lansing — and he needs a wingman. Tony is elected. And Janet even pushes him to go — it’s his duty.

Whitmore shows up at Tony and Janet’s apartment just as a panicked Janet discovers Tony had gone on his mission without his gun. Whitmore sees his daughter in her and decides to throw a scare in the boys without arresting them or revealing the truth to her.

That’s going to cost him.

Before the evening is over, Whitmore has taken a bullet and Leigh has blabbed to the press how her husband was hunting spies.

It’s been one of those days. And it’s about to get worse.

Because the CIA, more than a little miffed that the FBI is running a spy op without them, shows up. Seems the boys have drawn out an actual KGB cell. Now the FBI has to keep quiet and use the boys to draw out the real spies.

They should have known better.

Which is how the boys end up kidnapped by Russian spies Simon Oakland and Larry Storch, drugged, and locked in the sub basement of the Empire State Building — which they mistake for a Russian sub and proceed to sink while singing patriotic songs.

Which explains why it is snowing on some floors of the building and sweltering on others, not to mention the geyser spouting from the roof. And they thought the cleanup after King Kong was rough.

In the wrong hands, this kind of froth can go horribly wrong, but when everyone involved is a seasoned pro, and sheer charm and skill compete with fast quips and sheer nonsense, the result is a souffle of a movie, smart, silly, and great fun.

Don’t tune this one in looking for great art, but if belly laughs are the mood you are in, this is the perfect film. When you watch today’s latest comedy fall flat on its face at the mall and see ham-handed performances and obvious direction, you can appreciate how hard this is to do, and wonder that in this period it was done so well so often.

At the time this must have seemed just another playful comedy from a team of pros. Today it seems like art.

Dying is easy, comedy is hard. But if you do it right, it looks easy. And isn’t that the trick in farce, not to let the audience see how hard the actors are working to make it all seamless and easy?

On that level, this one is the highest of art.

TCM Alert: Monday, July 6. 6:00 PM. Who Was That Lady? (1960)

A cheating husband convinces his wife his flirtations are actually spy missions. Cast: Tony Curtis, Janet Leigh, Dean Martin. Dir: George Sidney. BW-114 mins, TV-G, Letterbox Format.

Thu 2 Jul 2009

THE SYSTEM. Bryanston Films, UK, 1964. Released in the US as The Girl-Getters, American International Pictures, 1966. Oliver Reed, Jane Merrow, Barbara Ferris, Julia Foster, David Hemmings. Director: Michael Winner.

There’s not a crime to be seen in this British-made movie, unless it’s the breaches of trust committed by a group of local lads who prey on the girls (birds, or thrushes) who come down from London and elsewhere to their small bailiwick on the sea every summer. Seduce and abandon, is their modus operandi, and their system is simple.

The leader of their lot, a chap named Tinker (Oliver Reed) has a job as a roving beach photographer.

He takes pictures of likely victims, obtains their local addresses, and distributes the same to the others of the group. When the summer’s over, they’ve left their ladies with lots of memories, perhaps, and – also perhaps – many of the memories are good ones. But lasting ones? Hardly ever.

No big crimes involved here, right? There are lots of swinging sixties beach party scenes, and the film is certainly not without lightness and humor, but no Annette Funicello beach blanket movie is this. If ever a film might be called Noir without even the hint of a murder being committed, it might be The Girl-Getters.

The question is, as it slowly dawns on Tinker, is who are the Takers and who are the Taken?

His pursuit of the wealthy Nicola (Jane Merrow) only shows how strong the “caste system” in England really was, and how futile it may have been to fight it. The one-set tennis match he plays with one of Nicola’s gentlemen friends, or tries to, and then tries to laugh it off, is a turning point that comes, one supposes, in everybody’s life – at which time they learn their limitations, and at the same time learn they cannot do anything about it.

The glowing embers behind Oliver Reed’s fiery, dark-shadowed eyes, and his memorable performance in this film, show that when the occasion presented itself, he was one of the finest actors of his day. Up until this movie, most of his work was done for Hammer Films, but I’d like to think that a lot of doors were opened to him afterward.

Not that The Girl-Getters was recognized as anything close to a work of art at the time, but it was among the vanguard of British films dealing with modern (if not mod) themes such as class differences and sexual awareness like Alfie and Georgy Girl (both 1966) that turned the world of film-making upside down.

I didn’t see The Girl-Getters back then, but that’s the era when I started to really enjoy what film-making was all about, rather than simply film-watching. Blow-Up (1966 as well, and starring David Hemmings, who also had a small role in this earlier movie) was a revelation to me, nor was I the only one who felt that way.

Thu 2 Jul 2009

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

JACK S. SCOTT – The Poor Old Lady’s Dead.

Harper & Row, US, hardcover, 1976. Reprint paperback: Popular Library, 1980. First published in the UK: Robert Hale, hc. 1976.

The Chief Inspector had come down with a bug and the Superintendent was not aware of it until Detective Inspector Rosher had taken over the investigation. So the tumble down the stairs by a little old lady at the Haven, an old folks’ home, remains in the ham-fisted hands of Old Blubbergut, as he is unaffectionately known to his colleagues and his underlings.

Rosher has to deal with an alderman who is the dead lady’s nephew and quite influential in the town, and finesse and subtlety are not Rosher’s strong points, if they are points of his at all.

A subplot involves Rosher’s unhappy and hapless assistant, who has to suffer not only from his superior’s taunts but from the demands of a pregnant mistress who, quite reasonably, wants him to leave his wife and marry her.

Rosher can be compared with [Joyce Porter’s] Chief Inspector Wilfrid Dover in some ways, only Dover is a caricature, a grotesque, and funny. Rosher is unfunny and very close to real.

He toadies to his superiors. As for his underlings, “Strangely, he was not unpopular with the rank and file, provided they were on a lowly rung and unlikely to rise far above it.” Like Dover, he cadges meals and drinks from the unfortunate juniors who have to work with him. His personal habits aren’t very pleasant, either.

As some other authors before him have discovered when they made their main character unpleasant, a continuing character must receive some empathy from the reader or be a burlesque like Dover. Otherwise, the normal reader will not buy further books in the series.

Scott made Rosher more appealing and more human, though still not particularly pleasant, as the series advanced. Read this first recorded case of Rosher for a good investigation, some rather bitter humor, and to discover what he was like in the beginning.

Then read the rest of Scott’s novels featuring Rosher. They become even more enjoyable as Rosher mellows somewhat.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 10, No. 3, Summer 1988.

Bibliographic Data: [Taken from the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin.]

ROSHER, INSP. (Sgt.) ALFRED STANLEY “ALF”. Series character created by Jack S. Scott.

The Poor Old Lady’s Dead (n.) Hale 1976; Harper, 1976.

The Shallow Grave (n.) Hale 1977; Harper, 1978.

A Clutch of Vipers (n.) Collins 1979; Harper, 1979.

The Gospel Lamb (n.) Collins 1980; Harper, 1980.

A Distant View of Death (n.) Collins 1981; Ticknor, 1981, as The View from Deacon Hill.

The Local Lads (n.) Collins 1982; Dutton, 1983.

An Uprush of Mayhem (n.) Collins 1982; Ticknor, 1982.

All the Pretty People (n.) Collins 1983; St. Martin’s, 1984.

A Death in Irish Town (n.) Collins 1984; St. Martin’s, 1985.

A Knife Between the Ribs (n.) Collins 1986; St. Martin’s, 1987.

Editorial Comment:

I may be wrong, but I don’t have any strong feeling that either Inspector Rosher or his creator Jack S. Scott are remembered by more than a handful of mystery readers today, some 20 or 30 years later. Back in the 1970s and early 80s, I’m fairly sure that Joyce Porter’s Inspector Dover’s books were more popular than Rosher’s, and I’m sure that even the obnoxious Dover is now little more than a fading memory, alas.

« Previous Page — Next Page »